По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

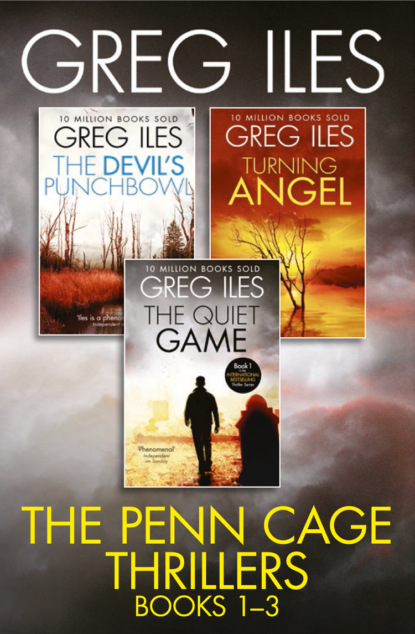

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“And if you lose? Back to white-shoe law in Chicago?”

His smile slips for a nanosecond.

“You said my family is in danger, Mr. Johnson.”

“Shad, please. Short for Shadrach.”

“All right, Shad. Why is my family in danger?”

“Because of your sudden interest in a thirty-year-old murder.”

“I have no interest in the murder of Del Payton. And I intend to make a public statement to that effect as soon as possible.”

“I’m relieved to hear you say that. I must have taken fifty calls today asking what I’m doing to help you get to the bottom of it.”

“What did you tell them?”

“That I’m in the process of putting together the facts.”

“You didn’t know the facts already?”

Johnson examines his fingernails, which look professionally manicured. “I was born here, Mr. Cage, but I was sent north to prep school when I was eleven. Let’s focus on the present, shall we? The Payton case is a sleeping dog. Best to let it lie.”

The situation is quickly clarifying itself. “What if new evidence were to come to light that pointed to Payton’s killer? Or killers?”

“That would be unfortunate.”

His candor surprises me. “For local politicians, maybe. What about justice?”

“That kind of justice doesn’t help my people.”

“And the Payton family? They’re not your people?”

Johnson sighs like a man trying to hold an intelligent conversation with a two-year-old. “If this case were to be dragged through the newspapers, it would whip white resentment in this town to a fever pitch. Black people can’t afford that. Race relations isn’t about laws and courts anymore. It’s about attitudes. Perceptions. A lot of whites in Mississippi want to do the right thing. They felt the same way in the sixties. But every group has the instinct to protect its own. Liberals keep silent and protect rednecks for the same reason good doctors protect bad ones. It’s a tribal reaction. You’ve got to let those whites find their way to the good place. Suddenly Del Payton is the biggest obstacle I can see to that.”

“I suppose whites get to that good place by voting for Shad Johnson?”

“You think Wiley Warren’s helping anybody but himself?”

“I’m not Warren’s biggest fan, but I’ve heard some good things about his tenure.”

“You hear he’s a drunk? That he can’t keep his dick in his pants? That he’s in the pocket of the casino companies?”

“You have evidence?”

“It’s tough to get evidence when he controls the police.”

“There are plenty of black cops on the force.”

Johnson’s phone buzzes. He frowns, then hits a button and picks up the receiver. “Shad Johnson,” he says in his clipped Northern accent. Five seconds later he cries “My brother!” and begins chattering in the frenetic musical patois of a Pine Street juke, half words and grunts and wild bursts of laughter. Noticing my stare, he winks as if to say: Look how smoothly I handle these fools.

As he hangs up, his assistant sticks his head in the door. “Line two.”

“No more calls, Henry.”

“It’s Julian Bond.”

Johnson sniffs and shoots his cuffs. “I’ve got to take this.”

Now he’s the urbane attorney again, sanguine and self-effacing. He and Bond discuss the coordination of black celebrity appearances during the final weeks of Johnson’s mayoral campaign. Stratospheric names are shuffled like charms on a bracelet. Jesse. Denzel. Whitney. General Powell. Kweisi Mfume. When the candidate hangs up, I shake my head.

“You’re obviously a man of many talents. And faces.”

“I’m a chameleon,” Johnson admits. “I’ve got to be. You know you have to play to your jury, counselor, and I’ve got a pretty damn diverse one here.”

“I guess running for office in this town is like fighting a two-front war.”

“Two-front war? Man, this town has more factions than the Knesset. Redneck Baptists, rich liberals, yellow dog Democrats, middle-class blacks, young fire eaters, Uncle Toms, and bone-dumb bluegums working the bottomland north of town. It’s like conducting a symphony with musicians who hate each other.”

“I’m a little surprised by your language. You sound like winning is a lot more important to you than helping your people.”

“Who can I help if I lose?”

“How long do you figure on sticking around city hall if you win?”

A bemused smile touches Johnson’s lips. “Off the record? Just long enough to build a statewide base for the gubernatorial race.”

“You want to be governor?”

“I want to be president. But governor is a start. When a nigger sits in the governor’s mansion in Jackson, Mississippi, the Civil War will truly have been won. The sacrifices of the Movement will have been validated. Those bubbas in the legislature won’t know whether to shit or go blind. This whole country will shake on its foundations!”

Johnson’s opportunistic style puts me off, but I see the logic in it. “I suppose the black man who could turn Mississippi around would be a natural presidential candidate.”

“You can thank Bill Clinton for pointing the way. Arkansas? Shit. Mississippi is fiftieth in education, fiftieth in economic output, highest in illegitimate births, second highest in welfare payments, the list is endless. Hell, we’re fifty-first in some things—behind Puerto Rico! I turn that around—just a little—I could whip Colin Powell hands down.”

“How can you turn this town around? Much less the state?”

“Factories! Industry! A four-year college. Four-lane highways linking us to Jackson and Baton Rouge.”

“Everybody wants that. What makes you think you can get it?”

Johnson laughs like I’m the original sucker. “You think the white elite that runs this town wants industry? The money here likes things just the way they are. They’ve got their private golf course, segregated neighborhoods, private schools, no traffic problem, black maids and yard men working minimum wage, and just one smokestack dirtying up their sunset. This place is on its way to being a retirement community. The Boca Raton of Mississippi.”

“Boca Raton is a rich city.”

“Well, this is a mostly poor one. One factory closed down and two working half capacity. Oil business all but dead, and every well in the county drilled by a white man. Tourism doesn’t help my people. Rich whites or segregated garden clubs own the antebellum mansions. That tableau they have every year, where the little white kids dance around in hoop skirts for the Yankees? You got a couple of old mammies selling pralines outside and black cops directing traffic. You see any people of color at the balls they have afterward? The biggest social events in town, and not a single black face except the bartenders.”

“Most whites aren’t invited to those balls either.”