По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

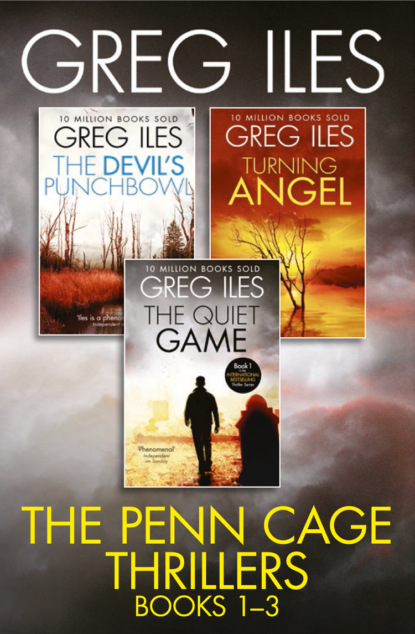

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Don’t think I’m not pointing that out in the appropriate quarters.”

“Mayor Warren doesn’t pursue industry?”

“Wiley Warren thinks riverboat gambling is our salvation. The city takes in just over a million dollars from that steamboat under the hill, while the boat drains away thirty million to Las Vegas. With that kind of prosperity, this town will be dead in five years.”

I glance at my watch. “I thought you brought me here to warn me.”

“I’m trying to. For the first time in fifty years we’ve got a major corporation ready to locate a world-class factory here. And you’re trying to flush that deal right down the toilet.”

“What I said in the paper won’t stop any company serious about locating here.”

“You’re wrong. BASF is a German company. They may be racists themselves, but they’re very sensitive to racial issues in foreign countries.”

“And?”

“They have concerns about the school system here.”

“The school system?”

“The public school is eighty percent black. The population’s only fifty percent black. BASF’s management won’t put their employees into a situation where they have to send their kids to expensive and segregated private schools for a decent education. They have to be convinced that the public schools are safe and of excellent quality.”

“And is that the case?”

“They’re safe enough, but the quality’s not the best. We’ve established a fragile consensus and convinced BASF that the public school is viable. We’ve developed all sorts of pilot programs. Those Germans are damn near committed to build here. But if the Payton case explodes in the media, BASF will crawfish so fast we’ll finally hear that giant sucking sound Ross Perot always whined about.”

I hold up my hands. “I have no interest in the case. I made a couple of comments and attracted the attention of Payton’s family. End of story.”

As Johnson smiles with satisfaction, my defensive tone suddenly disgusts me. “But I’ll tell you this. The harder people try to push me away from something, the more I feel like maybe I ought to take a look at it.”

He leans back and eyes me with cold detachment. “I’d think long and hard before I did that. Your little girl has already lost one parent.”

The words hit me like a slap. “Why do I get the feeling you might be the danger you warned me about?”

He gives me a taut smile. “I’m just trying to do you a favor, brother. This town looks placid, but it’s a powder keg. Drop by McDonald’s or the Wal-Mart deli and watch the black workers serve blacks before whites who got there first. Blacks are angry here, but they don’t know how to channel their frustration. What you’ve got here are blacks descended from those who were too dumb to head north after the Civil War or the world wars. No self-awareness. They take things out on whitey however they can. A while back, some black kids started shooting at white people’s cars. Killed a father of three. There’s a white backlash coming, and when it comes, there’s enough resentment among black teenagers to start a war. That’s what you’re playing with. Not to mention whoever killed Del Payton. You know those cracker bastards are still out there somewhere.”

“Sounds to me like Del Payton died in vain.”

“Payton was a paving stone in the road to freedom. No more, no less. And right now he’s best honored by leaving him lie.”

I stand, my face hot. “I’ve got to be somewhere.”

“When you get to your party, tell Wiley Warren I’m going to whip his lily-white ass.”

I pause at the door and look back. Johnson already has the phone in his hand.

“I think you’re underestimating blacks in this town,” I tell him. “They’re smarter than you give them credit for. They see more than you think.”

“Such as?”

“They can see you’re not one of them.”

“Don’t kid yourself, Cage. I’m Moses, cast onto the waters as a child and raised by the enemy. I prospered among the mighty and now return to show my people the way!”

In an instant the candidate’s voice has taken on the Old Testament cadence and power of a young Martin Luther King.

As I gape, he adds in his mincing lawyer’s voice: “Next time come over to campaign headquarters south. It’s on Main Street. The atmosphere’s more your style. Genteel and Republican, the way the old white ladies like it. Over there I’m a house nigger made good.”

Johnson is still laughing when I leave the building.

The sky is deep purple, the warm night falling to a sound-track of kicked cans, honking horns, shouting children, and squealing tires. The smell of chicken sizzling on the open pit pulls my head in that direction. Two black teenagers on banana bikes whizz toward me as I stand beside the BMW. I’m about to wave when one spits on the hood of my car and zips past, disappearing into a cloud of dark laughter. I start to yell after them, then think better of it. I did not bring the pistol my father advised me to, and I don’t need to start the riot Shad Johnson just warned me about. I get into the BMW, start it, and head south toward the white section of town.

I’ve hardly begun to reflect on Johnson’s words when I notice the silhouette of a police car behind me. Blinding headlights obscure its driver, but the light bar on the roof leaves no doubt that it’s a cop. As he pulls within fifteen yards of my rear bumper and hangs there, it hits me. I’m driving a seventy-five-thousand-dollar car in the black section of town. Some eager white cop is probably running my father’s plate right now, checking to see whether the BMW has been reported stolen. As we pass in tandem under a street lamp, I notice that the vehicle is not a police car but a sheriff’s cruiser. A sickening wave of adrenaline pulses through me as I wait for the flare of red lights, the scream of a siren.

Somewhere along here, this road becomes Linda Lee Mead Drive, named for Natchez’s Miss America. As I top the hill leading down to the junction with Highway 61, the cruiser pulls out and roars past me. I glance to my left, hoping to get a look at the driver.

The man behind the wheel is black.

He is fifty yards past me when both front windows of the BMW explode out of their frames, shattering into a thousand pieces. I whip my head to the right, trying to shield my eyes. My eardrums throb from sudden depressurization, and I instinctively slam on the brakes. As the back end of the car skids around, something hammers my door, sending a shock wave up my left thigh. The car comes to rest facing the right shoulder, blocking both lanes of the road. In the silence of the dead engine, the reality of my situation hits me.

Someone is shooting at me.

Frantically cranking the car, I notice the brake lights of the sheriff’s cruiser glowing red at the bottom of the hill, a hundred yards away.

It’s just sitting there.

As my engine catches, two bullets smash through the rear windshield, turning it to starred chaos. I throw the BMW into gear, stomp the accelerator, whip around, and start down the hill. Before I’ve gone thirty yards, the sheriff’s cruiser pulls onto the highway and races off toward town.

“Stop!” I shout, honking my horn. “Stop, goddamn it!”

But he doesn’t stop. The rifle must have made a tremendous noise, though I don’t remember hearing it. Maybe the exploding glass distracted me. But the black deputy in the cruiser must have heard it. Unless the weapon was silenced. This thought is too chilling to dwell on for long, since silenced weapons are much rarer in life than in movies, and indicate a high level of determination on the part of the shooter. But if the deputy didn’t hear the shots, why did he stop so long? There was no traffic at the intersection. For a moment I wonder if he could have fired the shots himself, but physics rules that out. The first bullet came through the driver’s window, while the deputy was fifty yards in front of me. The last two smashed the back windshield after the skid exposed it to the same side of the road.

My heart still tripping like an air hammer, I turn onto Highway 61, grab the cell phone, and dial 911. Before the first ring fades, I click End. Anything I say on a cell phone could be all over town within hours. The odds of catching the shooter are zero by now, and my father’s blackmail situation makes me more than a little reluctant to bring the police into our lives at this point.

Shad Johnson’s words echo in my head like a prophecy: A while back, some black kids started shooting at white people’s cars. Killed a father of three. But this shooting was not random. This morning’s newspaper article upset a lot of people—white people exclusively, I would have thought, until Shad Johnson disabused me of that notion. What the hell is going on? Johnson warns me that my family is in danger but gives no specifics, and ten minutes later I’m shot at on the highway? After being followed by a black deputy who doesn’t stop to check out the shooting?

Whoever was behind that rifle meant to kill me. But I can do nothing about it now. I’m less than a mile from my parents’ house, and my priority is clear: within an hour I will be talking to the district attorney about my father’s involvement in a murder case, and deciding how best to sting Ray Presley, a known killer.

NINE (#ulink_20536cd6-4e99-591e-9858-ee7dfb3a318f)

“Tom Cage, you dog! I can’t believe you came!”

In small towns the most beautiful women are married, and Lucy Perry proves the rule. Ten years younger than her husband—the surgeon hosting the party—Lucy has large brown eyes and a high-maintenance muscularity shown to perfection in a black silk dress that drapes just below her shapely knees. She also has suspiciously high cleavage for a forty-year-old mother of three, which I know she is, having been given a social update by my father on the way over to the party. Lucy uses the sorority squeal mode of greeting, which is always a danger in Mississippi. She flashes one of the brightest smiles I’ve seen off a magazine cover and throws her arm around my father.

“I’m here for the free liquor,” Dad says. “Not for Wiley Warren to pick my pocket.”

Lucy has a contagious laugh, and Dad has drawn it out. He’s one of the few people honest enough to use the mayor’s nickname within earshot of the man himself. Now Lucy looks at me as though she’s just set eyes on me.

“So this is the famous author.”