По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

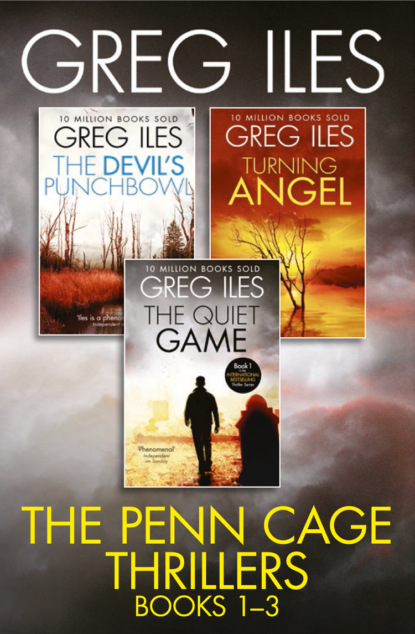

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“For what?”

“Research that I don’t have the time or resources to do.”

“What do you need to know?”

“You haven’t agreed to my condition yet.”

She mulls it over some more. “Why should I muzzle my paper to help you? How do I know you’ll solve the case any faster than I could?”

“Do you have a copy of the original police file?”

“No. But I’m working on a request for his FBI file under the Freedom of Information Act.”

“Don’t bother. You won’t get it. J. Edgar Hoover sealed the Payton file in 1968 for reasons of national security.”

She shakes her head in disbelief. “I smelled a Pulitzer the minute you told me about this case. Okay, deal. Tell me what you want, I’ll get it. Fast. But I want in on everything.”

“Fair enough,” I say, wondering if I mean it. A half hour ago Cilla called from Houston. After spending hours tracing the names on Peter Lutjens’s list, and finding most retired or dead, she lucked into a fan of mine. He hadn’t worked the Payton murder, but he remembered it. More important, he numbered Special Agent Dwight Stone, the field agent Althea Payton recalled so fondly, among his old friends. Stone is retired and living outside Crested Butte, Colorado. Cilla called him and found him friendly enough until she mentioned Del Payton, at which time Stone bluntly stated that he would not discuss the Payton case with me or anyone. I intend to test his resolution very soon.

“So, what do you want to know?” Caitlin asks.

“I need everything you can get on Leo Marston. You know who he is?”

“Sure. A big-time attorney everybody calls Judge because he served on the state supreme court. I tried to get a comment from him for my Payton story, but I couldn’t get through. His secretary’s a cast-iron bitch.”

“You should meet his wife.”

“The woman who baptized you at the cocktail party?”

“That’s her.”

“No, thanks. Why Marston?”

“You don’t need to know that yet.”

She doesn’t like this response. “Who else?”

I’d like a detailed bio of Ray Presley, but Caitlin can’t access the kind of information I need on him. “Just start with Marston. Companies he owns, whole or in part. Personal and political connections. His tax returns if you can get them.”

Jenny reappears at our table, her dark eyes watching me with a disconcerting intensity. “Have you decided?”

“I’m not really hungry,” I confess, handing her my unopened menu. “I had to eat before I came. My daughter helped cook.”

“How old is she?”

“Four.”

“That’s a fun age.”

“Are they working on my ribs back there?” Caitlin asks.

“They’ll be out in a minute.” Jenny gives her a curt smile and heads back to her station.

“You owe me an answer too, remember?” says Caitlin. “You’re the most liberal person I’ve met here, as far as race goes. You’re fascist on the death penalty, of course, but we’ll skip that for now. How did you wind up so different from other people here?”

“It’s simple, really. My father.”

She puts her last shrimp into her mouth and chews slowly, her green eyes luminescent in the soft light. “Let’s hear it.”

“This never sees print. It’s no big deal, but it’s personal. That’s something we need to get straight right now. If we’re going to work together, some things never see print.”

“No problem. It’s in the vault.”

“I remember three defining moments with my father when I was growing up. The first had to do with race. Most kids I grew up around used the word ‘nigger’ the same way they used ‘apple’ or ‘Chevrolet.’ So did their parents and grandparents before them. One night, at home, I used it the same way. My father got out of his chair, turned off the television, and came and sat beside me. He said, ‘Son, I grew up working in a creosote plant right alongside colored people. And they’re just like you and me. No better, no worse. We don’t say that word in this house.’ Then he turned the TV back on. And I stopped saying nigger.

“A couple of years later, the thing to be was a hippie, and I tried my best. Grew my hair down my back, smoked grass, the whole bit. I heard hippies on TV saying the ‘pigs’ this, the ‘pigs’ that. The cops, you know? So, one day, riding in the car, I said something about the pigs. My father pulled onto the shoulder, turned around, and said, ‘Son, if we had to go three days in this country without police, it wouldn’t be a place you’d want to live. We don’t use that word.’ And I never used it again.”

Caitlin’s eyes shine with fascination. “And the third moment?”

“I was fifteen, and I’d been sleeping with this older girl from the public school who went off to junior college. I stole the family car a couple of times to go to see her. In the kitchen one night my mother told me I couldn’t do that anymore. In my hormone-intoxicated state, I said, ‘Mom, why are you being such a bitch about this?’”

“Oh, my God.”

“My dad clocked me. This man of reason who had never lifted a finger to me slapped me an open-handed blow that damn near blacked me out. I was spiritually stunned. But it was the right blow at the right moment. The only one I ever needed. It drew the line for me.”

Caitlin nods slowly, a smile on her lips. “Thank you for telling me that. You’re lucky to have a father like that.”

I wonder what she’d say if she knew that an hour ago my wonderful father and I sank a murder weapon in a swamp.

Her barbecued ribs finally arrive, and we run through a half dozen other subjects while she eats. Journalism, my law career, publishing. She grew up with money but worked hard to make her own mark. She did internships with the New York Times and the Washington Post, traveled extensively overseas, and worked a year for the Los Angeles Times. When she asks obliquely about the Hanratty execution, I change the subject.

“Where do you live? I don’t picture you in an apartment.”

She smiles and wipes her mouth with a napkin, knowing I’m evading her question. “I pretty much live at the paper. But I did buy a house on Washington Street.”

“Roughing it, huh?” Washington Street is old Natchez; most of the town houses there sell for over three hundred thousand dollars.

“I need my space,” she says frankly. “You should come see it. It was completely restored just before I bought it.”

A wave of warmth passes over my face. Is she hinting that I should go to her house after dinner? I’ve been out of circulation for years, and she’s only twenty-eight. In the realm of dating, she is the expert, not me.

“Do you need to get home?” she asks. “I’ll bet Annie’s waiting up for you.”

That is what she’s suggesting. I look at my watch to conceal the fact that I’m blushing. “Annie’s falling asleep about now. I’m okay for a bit.”

“Well … would you like to see it? We could have some tea and talk. Or we could just take a ride. You could show me the real Natchez.”

In the dark? But the automatic rejections I’ve practiced since Sarah’s death don’t come to me. “A ride might be fun.”