По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

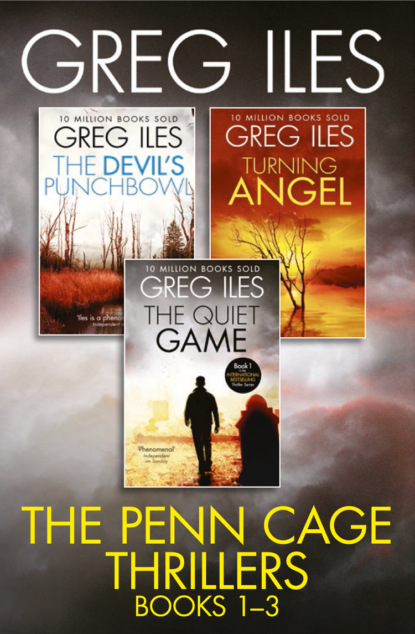

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We should? “Why don’t you call me? Then I can skip speaking to your father.”

She lets this pass. “I will. Wait and see.”

“I’d better find Annie. We’ll be boarding soon.”

She reaches out and takes my hand. “It’s strange, isn’t it?”

“What?”

“Twenty years after high school, and suddenly we’re both free.”

I can’t believe she said it. Gave voice to something I would not even allow myself to think. “There’s a difference, Livy. I didn’t want to be free.”

She pales, but quickly recovers and squeezes my hand. “I know you didn’t. I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to put it that way.”

I take back my hand. “I know. I’m sorry too. I’ve got to run.”

I turn to go in search of Annie and Caitlin, but after ten steps I stop and look back. I don’t want to. I have to.

Livy hasn’t moved. She’s looking right at me with a provocative expression of both regret and hope. She holds up her right hand in farewell, then turns and disappears into the crowd.

“Daddy, was that lady a movie star?”

Annie and Caitlin have reappeared at my side.

“No, punkin. Just someone I went to school with.”

“She looks like somebody on TV.”

She probably does. Livy is a living archetype of American good looks: not a Mary Tyler Moore but a warmer, more accessible Grace Kelly. A Southern Grace Kelly.

“I didn’t think she looked like a movie star,” Caitlin announces.

“What do you think she looks like?” I ask, not sure I want to hear the answer.

“A self-important B-I-T-C-H.”

“Hey,” Annie complains. “What’s that spell?”

“Witch,” says Caitlin, tickling her under the arms, which triggers explosive giggles. “The Masters intuition never fails,” she adds, looking up at me. “You’ve got it bad for her, don’t you?”

“What? Hell, no.”

“Daddy said a bad word!” Annie cries.

“Daddy told a fib,” says Caitlin. “And that’s worse.”

“I think I need a drink.”

The ticket agent announces that first class will begin boarding immediately.

“First love?” Caitlin asks in a casual voice as we move through the mass of passengers funneling toward the gate.

“It’s a long story.”

She nods, her eyes knowing. “If short stuff here goes to sleep on the plane, that’s a story I wouldn’t mind hearing.”

Perfect.

Airplanes work like a sedative on Annie. After drinking a Sprite and eating a bag of honey-roasted peanuts, she curls up next to Caitlin and zonks out. At Caitlin’s suggestion, I move her across the aisle to my seat and, when she begins to snore again, move back across the aisle beside Caitlin.

“You’re going to make me drag it out of you?” she says.

I say nothing for a moment. Certain relationships do not lend themselves to conversational description. Emotions are by nature amorphous. When confined to words, our longings and passions, our rebellions and humiliations often seem melodramatic, trivial, or even pathetic. But if Caitlin is going to help me destroy Leo Marston, she needs to know the history.

“Every high school class has a Livy Marston,” I begin. “But Livy was special. Everyone who ever met her knew that.”

“Marston? She said her name was Sutter.”

“Her maiden name was Marston.”

“Marston … Marston. The guy you asked me to check out? The D.A. when Payton was killed? Judge Marston?”

“He’s Livy’s father.”

“God, it’s so incestuous down here.”

“Like Boston?”

“Worse.”

Caitlin calls the flight attendant and orders a gimlet, but this is beyond the resources of the galley. There seems to be a nationwide shortage of Rose’s Lime Juice. She orders a martini instead.

“So,” she says, “what made her so special?”

“How many people were in your graduating class?”

“About three hundred.”

“Mine had thirty-two. And most of those had been together since nursery school. It was like an extended family. We watched each other grow up for fourteen years. And those thirty-two people did some extraordinary things.”

“Such as?”

“Well, there’s high school, and then there’s life. Out of thirty-two people we had six doctors, ten lawyers, a Grammy-winning record producer, a photographer who won the Pulitzer last year—”

“And you,” she finishes. “Best-selling novelist and legal eagle.”

“Every class thinks it’s special, of course. But in a town as small as Natchez, and a school as small as St. Stephens, you have to have something like a genetic accident to get a class like ours. Our football team had eighteen people on it. Everyone played both ways. And we were ranked in the top ten in the state in the rankings of public schools. That’s ranked against schools like yours, with seventy players on the squad. Our baseball team was the first single-A team in the history of Mississippi to win the overall state title.”