По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

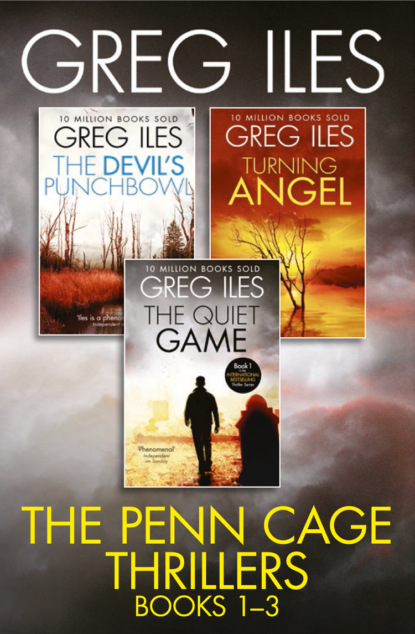

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Maybe she got pregnant. Went off and had the baby somewhere.”

“I thought about that. But this was the late seventies, not the fifties. Her older sister had gotten pregnant a few years before, and she had an abortion, even though they were Catholic. Livy would have done the same thing. She wouldn’t have let anything slow down her career.” There’s another reason I’m sure pregnancy is not the answer, but there’s no point in getting clinical about it.

“Why did she go to the University of Virginia?”

“I think because it was far from Mississippi but still the South. She got an unlisted number, cut herself off from her old friends. By the time my father’s trial got going, I didn’t care anymore.”

“You didn’t ask her why her father was going after yours?”

This memory is one of my worst. “I flew up to Charlottesville a week before the trial, to try to get her to make Leo drop the case. My dad had already had a heart attack from the stress. She said she thought it was just a normal case, and that her father wouldn’t listen to her opinion anyway. She was back in her high school queen mode, winning hearts and minds at UVA. It was like talking to a stranger.” I take a burning sip of Scotch. “I wanted to kill her.”

“Yes, but you loved her. You’re still in love with her.”

“No.”

Caitlin smiles, not without empathy. “You are. You always will be.”

“That’s a depressing thought.”

“No. Just recognize it and move on. Livy’s not the person you think she is. Nobody could be. And you’d better be careful. She just separated from her husband, and you’re still grieving over your wife. She could really mess you up.”

“I’m no babe in the woods, Caitlin.”

Her smile is timeless. All men are babes in the woods, it says. “You’re trying to destroy her father now. How do you think she’ll react to that?”

“I don’t know. She has a love-hate relationship with him. It’s like something out of Aeschylus. She knows he’s done terrible things, but in some ways she’s just like him.”

“You should try very hard to keep that in mind.”

“Why?”

She takes a pair of headphones from her lap, plugs them into the seat jack, and starts flipping through her channel guide. “How long has it been since you’ve seen her?”

“She came to my wife’s funeral. We only spoke for a moment, though.”

“Before that.”

“A long time. Maybe seventeen years.”

“You pull the lid off something that might get her father charged with capital murder, and suddenly she shows up like magic?”

“What are you saying? That her father called her to Natchez to … to influence me somehow? Because of your newspaper story?”

Caitlin shrugs. “I don’t want to upset you, but that’s what I’m saying.”

She gives me a sad smile and puts on the headphones.

TWENTY (#ulink_fcb3e69e-d00e-59b8-aa65-85f948411945)

I thought I was the last person to arrive in the witness room at Huntsville Prison until FBI Director John Portman walked in, flanked by two field agents who shadowed him like centurions guarding a Roman emperor. Up to that point the preparations for the execution had proceeded with the tense banality that characterizes them all.

I had arrived to find the room nearly full. My old boss, Joe Cantor, motioned me to the empty chair beside Mrs. Givens, the closest relative of the victims. The curtain was drawn over the window of the extermination chamber, but I knew Arthur Lee Hanratty was already strapped to the gurney behind it, while a technician searched for veins good enough to take large-bore IV lines.

I hadn’t seen Mrs. Givens for eight years, but the smell of cigarettes on her clothes brought back everything, a nervous woman who chain-smoked through every pretrial meeting and rushed for the courthouse door at every recess. She had a Bible in her lap tonight, open to Job. When I touched her hand, she clenched my wrist and asked if I’d seen many executions before, and if they were difficult to watch. In a quiet voice, I explained the procedure: sodium thiopental to shut down Hanratty’s brain; Pavulon to paralyze him and stop his breathing; potassium chloride to stop his heart.

“You mean they put him to sleep before they give the bad chemicals?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

“Will he be able to say anything?”

“I’m afraid so. He’ll be allowed to make a final statement for the record.”

She patted the leather-bound book in her lap. “I’m not going to listen. I’m going to read the Good Book then.”

“That sounds like a good idea.” Killers often asked forgiveness at the end, but that wasn’t Hanratty’s style.

That was the moment that the door at the back of the room opened. Some reporters in front of me turned around, and recognition and amazement lit their faces. I turned and froze, confronted by the most unlikely vision I thought I would see at midnight in Texas.

John Portman looks like a walking advertisement for Brooks Brothers: thin and strong but a bit stiff, handsome with a longish face framed by hair gone gracefully gray. He was fifty-five when he and I crossed swords over Arthur Lee Hanratty, but he looked forty. He scarcely looks older now. I’ve always sensed a Dorian Gray aura about him, as though he were committing secret sins that never registered on his countenance.

I can’t imagine what he’s doing here. There’s no upside for him. None I can see, anyway. Maybe it’s as simple as revenge. His experience with Hanratty almost derailed his juggernaut career, and Portman definitely knows how to carry a grudge. Watching Hanratty die might give him a great deal of satisfaction.

While his guards take up positions against the wall, he walks straight to the front row and sits in the empty chair next to Joe Cantor, who looks as surprised as the rest of us. I half expect Portman to turn and give me a grim smile, but he stares straight ahead at the curtain beyond which Arthur Lee Hanratty will soon take his last breath.

As we wait in silence, I realize I’m listening for the ring of a telephone. Conditioned by movies—and by a couple of real-life experiences—I run through the dramatic possibilities: the last-minute pardon, the hard-won stay courtesy of some crusading young lawyer from the ACLU. But that won’t happen tonight. Even the mob of placard-bearing demonstrators outside the walls looked smaller and more subdued than usual as I passed through it. A few hundred people chanting dispiritedly in the Texas rain. Arthur Lee Hanratty is a poster boy for capital punishment.

Suddenly the curtain is drawn back, revealing a man in an orange jumpsuit on an execution gurney, which looks like a medical exam table that has been welded to the floor. Strapped to the gurney with IV lines running saline into his arms, Hanratty doesn’t look much like the madman I remember—a killer with the bunched and corded muscles of the convict weightlifter—but like every other man I’ve seen on that table. Helpless. Doomed. He reminds me of Ray Presley, though Hanratty has the lamplike eyes of the fanatic, not the cold rattlesnake beads of Presley.

The warden retained a good venipuncturist tonight—or else Hanratty has good veins—because the execution is proceeding on schedule. The warden stands with two guards against the wall behind the gurney. At 11:58 he steps forward and asks Hanratty if he has any final words. I once watched a man sing “Jesus Loves Me” with tears in his eyes at this point, and die with the song on his lips. But I don’t think that’s what’s coming now.

Hanratty cranks his neck around and searches our eyes one witness at a time, like a brimstone preacher trying to put the fear of Hell into his congregation. I’ve always felt that the window here should be one-way glass, to prevent the killer from making eye contact with the spectators. But the families of murder victims don’t want it that way. Many of them want their faces to be the last thing the condemned sees before he dies. When Hanratty finds my eyes, I give him nothing.

“Well, well, well,” he croons from the gurney, “everybody’s here tonight. We got Mr. Penn Cage, who got famous killing my brother and convicting my ass. We got Joe Cantor, who got reelected off Mr. Cage convicting my ass. And we got former U.S. Attorney Portman, head of the FBI. I’m flattered you came to see me off, Port. Ironic, ain’t it? If you could have covered up me killing that Compton nigger like you wanted to, none of us would have to be here tonight.”

The reporters devour this unexpected windfall like starving jackals. Surely, Portman must have known something like this could happen. The warden takes a step closer to the gurney. The word “nigger” has got him thinking about gagging Hanratty, though legally the condemned man is allowed to speak freely.

“After tonight,” Hanratty goes on, “there’ll only be one of us Hanrattys left. But that’s all right. My brother knows what to do. Some of you folks are gonna get a visit real soon. Some warm night when you least expect it, a deer slug’s gonna plow right through your brain. Or maybe through your kid’s brain—”

The warden motions to his guards.

“I got a right to speak!” Hanratty shouts, neck muscles straining.

The warden raises his hand, stopping the guards. He’d like to avoid being branded a fascist by the media if he can avoid it.

“Evening, Mrs. Givens,” Hanratty says in a syrupy voice. “I’ll be thinking ’bout your sister and your niece when they send me off to Jesus. I’ve thought about them many a night when I’m falling asleep. Yes, ma’am.”

Mrs. Givens’s shivering hand clenches my wrist like a claw.