По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

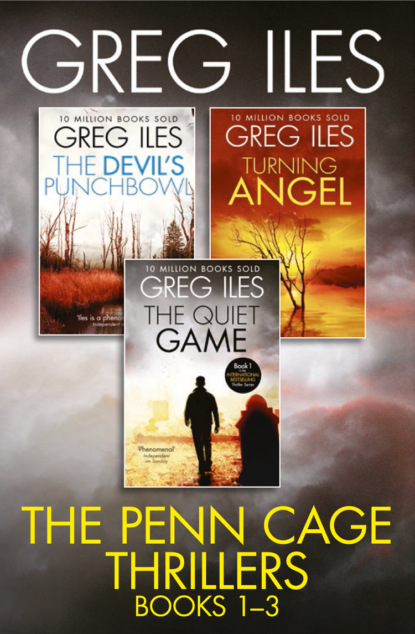

Greg Iles 3-Book Thriller Collection: The Quiet Game, Turning Angel, The Devil’s Punchbowl

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She rolls her eyes. “So you were big-time in Mississippi sports. Let’s call CNN.”

“Sports means a lot in high school.”

“What about academics?”

“Second-highest SATs in the state.”

“When do we get to Miss Perfect?”

“Livy was the center of all that. The star everyone revolved around. Homecoming queen, head cheerleader, valedictorian … you name it, she was it.”

Caitlin groans. “Gag me with a soup ladle.”

“If you plop most high school queens down at a major university, they’ll disappear like daisies at a flower show. Not Livy. She was head cheerleader at Virginia, president of the Tri-Delts, and made law review at the UVA law school.”

“She sounds schizophrenic.”

“She probably is. She was born to a man who wanted sons, in a decade when the cultural dynamic of the fifties was still alive and kicking in the South. She was a brilliant and beautiful girl with a mother who thought in terms of her marrying well and a father who wanted her to be president. She killed a ten-point buck when she was eleven years old, just to prove she could do anything a boy could.”

“Spare me the body count. I suppose she graduated, won the Nobel prize, and raised two-point-five perfect kids?”

I can’t help but laugh at the animosity Livy has inspired in Caitlin; it can only be based on the degree to which Livy has intimidated her. “Actually, she sold out.”

Caitlin cringes in mock horror. “Not the head cheerleader of the law review?”

“She took the biggest offer right out of law school and never looked back. Chased money and power all the way.”

“Who did she marry?”

“This is the part I like. She had this Howard Roark fixation. You know, the architect from Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead? She wanted the absolute alpha male, an artist-logician who wouldn’t take any shit off her or compromise once in his life.”

“Did she find him?”

“She married an entertainment lawyer in Atlanta. He represents athletes and rap singers.”

“There is justice,” Caitlin says, laughing. “Though I guess he made a lot more money than a Houston prosecutor.”

“Twenty times more, at least.”

“Why did you stay in the D.A.’s office so long? I thought most lawyers only did that for a couple of years to prep themselves for private defense work.”

“That’s true. Most people who stay are very different from me. Zealots, moralists. Jesuits, I call them. Military types who like to punish criminals. My boss was a lot like that.”

“So, why did you stay?”

“I was accomplishing something. I felt I was a moral counterweight to those people. Some liberals said I had an overdeveloped sense of justice. And that may be true. I convicted a lot of killers, and I don’t apologize for it. I believe evil should be held accountable.”

“Whoa, that was Evil with a capital E.”

“It’s out there. Take my word for it.”

“An overdeveloped sense of justice. Is that why you’re investigating the Payton case?”

“No. I’m doing that because of Livy Marston.”

Caitlin looks like I hit her in the head with a hammer. “What the hell are you talking about?”

I lean into the aisle and signal the flight attendant; it’s time for a Scotch. “Twenty years ago Livy’s father used every bit of his power to try to destroy my father. He didn’t succeed, but he separated Livy and me forever. And I never knew why.”

“And you think Marston is involved in the Payton murder?”

“Yes.”

“God, I’m trapped in a Southern gothic novel.”

“You asked for it.”

She finishes off her martini in a gulp. “I hope nobody’s going to ask me to squeal like a pig.”

I laugh as she orders another martini, amazed by how quickly the age difference between us has become irrelevant. I wonder how far apart we really are. Does she know that John Lennon and Paul McCartney were the greatest song-writers who ever lived? That the pseudo-nihilism of Generation X was merely frustrated narcissism? That I, at thirty-eight years old, am as trapped in my own era as a septuagenarian humming “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree With Anyone Else But Me” and dreaming of the agony of Anzio is trapped in his?

“Back up,” Caitlin says. “You and Livy were high school sweethearts?”

“No. For most of high school we were competitors. She only dated older guys, and no one steadily. She was her own person. She never wore a boy’s letter jacket or class ring. She needed nothing external to define her or make her feel accepted. But at some point we both realized we were destined for bigger futures than most people we knew. We were going to leave that town far behind. That awareness inevitably pulled us together. We both loved literature and music, both excelled in all our classes. We dated for four months at the end of our senior year. We were both going to Ole Miss in the fall, but she was going to Radcliffe for the summer—”

“Oh, my God,” Caitlin exclaims. “That magnolia blossom actually darkened the door of Radcliffe?”

“Aced every class, I’m sure. She wouldn’t let Yankees feel superior to her for a second.”

Caitlin makes a wry face, then sips her martini and looks out her window. “Was she good in bed?”

“A gentleman never tells.”

She turns and punches my shoulder. “Jerk.”

“What would you guess?”

“Probably. She has the intensity for it.”

Yes …

“How did her father split you up?”

“He took a malpractice case against my father and pressed it to the wall. My dad was exonerated, but the trial was so brutal it nearly broke him. There was no way Livy and I could work through that.”

Caitlin is watching me intently. “You’re leaving a lot out, aren’t you?”

Of course I am. How do we explain the abiding mysteries of our lives? “Livy never showed up at Ole Miss,” I say softly. “She disappeared. Fell off the face of the planet. Her parents told people she’d gone to Paris to study at the Sorbonne, but I called to check, and they had no record of her. A year later word filtered out that she’d just entered the University of Virginia as a freshman. I have no idea where she spent the previous year, and neither does anyone else.”