По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

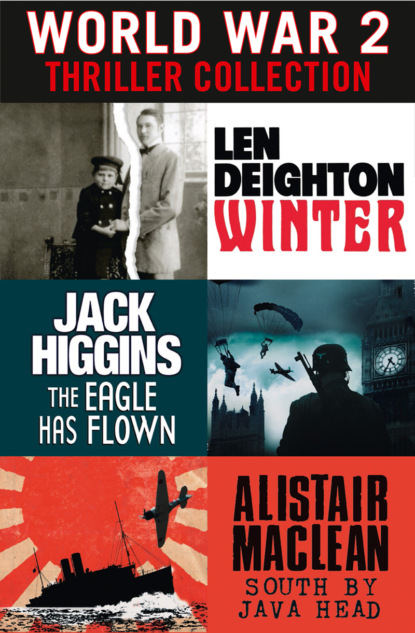

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘When the telephone rings, you make sure you answer it,’ said Peter.

‘I do, Herr Leutnant.’ He continued leaning against the gun.

‘You should be standing to attention, Hennig.’

‘I’m manning the gun, Herr Leutnant.’

The wretch always had an answer ready. And Peter well knew that any complaint about Hennig would not be welcome. Hennig played piano in the officers’ mess. He could be an engaging young man when he tried, and he had a lot of supporters amongst the senior ranks. When the beer and wine were flowing and the old songs were sung until the small hours of the morning, Hennig became a sort of unofficial member of the officers’ club. It would be a foolish young officer who punished him for what might sound like no reason but jealousy. For Peter would never be able to play the sort of music that got a party going. In this respect he admired Hennig’s talent and envied those years that Hennig had spent strumming untuned pianos for drunken clubgoers. Hennig always found under his fingertips the right melodies for the right moments. And he remembered them. He knew the tune the Kapitänleutnant had danced to the night he met his wife. He knew those bits of Strauss that the observation officer could hum. He knew when the captain might be induced to sing his inimitable tuneless version of ‘I’m Going to Maxim’s’ and changed key to help him; and he knew the hymn tunes for which there were words that could be sung only after the captain departed.

Peter Winter’s musical talent was the talent of the mathematician, and, as was the case with most mathematicians, Bach was his first musical choice. Peter’s love for Bach was a reflection of his upbringing, his social class, and the time and place in which he lived. There was a measured orderliness and formality to Bach’s music: a promise of permanence that most Europeans took for granted. Playing Bach, Peter displayed a skill and devotion that Hennig could never equal. But Hennig never played Bach. And Peter never played the piano in the officers’ mess, where Bach was not revered.

Peter went to the telephone, swung the handle round until the control gondola answered. ‘Upper gun position. Testing,’ said Peter.

‘Your voice is loud and clear, Herr Leutnant,’ said the petty-officer signalman.

Peter replaced the earpiece. ‘Carry on, Hennig,’ he said.

‘I will, Herr Leutnant,’ said Hennig. And as Peter started on the long and treacherous vertical ladder, he heard the loader titter. He decided it was better not to hear it.

As he picked his way back down the ladder to the keel, he thought about his exchange with Hennig. He knew he’d come out of it badly. He always came out of such exchanges badly. He didn’t have the right temperament to deal with the Hennigs of this world. He had tried, God knows he’d tried. Early in their first training flights, on one of the old Hansa passenger zeppelins, he’d talked to Hennig and suggested he apply for officer training. Hennig had taken it as some subtle sort of insult and had rejected the idea with contempt.

But in the forefront of Peter’s mind was the fact that Hennig had lately become more than friendly with Lisl Wisliceny, whom Peter considered his girl. Particularly hurtful was the latest letter from Lisl. Until now she’d been pressing Peter to become engaged to her. Peter, reluctant to face the sort of scene that his father would make in such circumstances, had found excuses. But in her latest letter Lisl had written that she now agreed with Peter, that they were both too young to think of marriage, and that she should see more people while Peter was away. And by ‘people’ she meant Erich Hennig. That much Peter was certain about. Only after Peter had taken Lisl to the opera did young Hennig suddenly begin to show his interest in this, the youngest of the Wisliceny daughters. And Hennig got far more opportunities to go to Berlin than Peter got. For the other ranks there were two weekend passes a month if they were not listed on the combat-ready sheet or assigned to guard duties. But officers were in short supply at the airship base. And, as any young officer knows, that meant that the junior commissioned ranks worked hard enough to prevent the shortage of officers, bringing extra work to those with three or more gold rings on their sleeve.

Damn Hennig! Well, Peter would show him. Little did Hennig realize it, but his insolence, and his pursuit of Peter’s girl, would be just what was needed to make Peter into the international-class pianist that Frau Wisliceny said he could become. From now on he would practise three hours a day. It would mean getting up at four in the morning, but that would not be difficult for him. There was a piano in the storage shed. Though it was old and out of tune, that would be no great difficulty. Peter could tune a piano, and there was a carpenter on the Dragon who would help him get it into proper working order, a decent old petty officer named Becker. He’d worked as an apprentice in a piano factory and knew everything about them.

For the next half-hour Peter was kept busy with his charts. Having missed his lunch, he became hungry enough to dip into his ration bag. The food supplied for these trips was not very appetizing. There were hardboiled eggs and cold potatoes, some very hard pieces of sausage and a thick slice of black rye bread. There was also a bar of chocolate, but for the time being he saved the chocolate. If they went high, where even the black bread turned to slabs of ice that had to be shattered with a hammer, the chocolate was the only substance that didn’t freeze solid. He took a hardboiled egg and nibbled at it. If he could get down to the rear-engine car, there might be a chance of some hot pea soup or coffee. The engineering officer let the mechanics warm it on the engine exhaust pipes. In some of the zeppelins there was constant hot coffee from an electric hot plate in the control gondola, but on this airship the captain wouldn’t allow such devices to be used because of the fire risk.

When his calculations were complete, Peter turned to watch the men in the control gondola. At the front was a seaman at the helm. He steered while another crewman beside him, at the same sort of wheel, adjusted the elevators to keep the airship level. This was said to be the most difficult job in the control room, although Peter had never tried his hand at it. A good elevator man was able to anticipate each lurch and wallow and turn the wheel to meet each gust of wind. The control gondola was like a little greenhouse into which machinery had been packed. The largest box, a sort of cupboard, was the radio, for keeping in touch with base and with the other airships. There was the master compass with an arc to measure the angle to the horizon, a variometer for measuring descent or climb, an electric thermometer to measure the temperature of the gas in the envelope, and there were the vitally important ballast controls. At the front, where the captain stood alongside the helmsman, was the bomb-release switchboard and a battery of lamps for signalling and for landing.

Tonight’s plan was simple: the main body of airships would attack London, approaching from over the Norfolk coast while two army airships were sent north to fool the defences by making a feint attack along the river Humber. The plan itself was good enough, although its lack of originality meant that the British would not be fooled.

And the attack started too early. Even the captain, a man whose formal naval training prevented him from criticizing the High Command or his senior colleagues, said it was a bit early when the first of the airships moved forward from the place at which they’d hovered for three hours. The whole idea of waiting was so that the sky would be totally dark when the airships crossed the English coastline. But it wasn’t dark. Even the English countryside, some six thousand feet below them, was not quite darkened. Peter had no trouble following the map. He could see the rivers, and many of the villages were brightly lit. And that meant that the British could see them. The alarms would go off, London would be made dim, and civilians would go to the bomb shelters. Worse, the pilots would stand by their planes and the gunners would load the guns; their reception would be a hot one.

All the time he watched the horizon; there was always some sort of glow from London, no matter how stringently the inhabitants doused their lights. Then he spotted it, and as they came nearer to London Peter could see the looping shape of the river Thames. There was no way that could be hidden. Suddenly the guns started. Flickers of light at first as the gunners tried to get the range, but then the flashes came closer. Staring down, Peter spotted the Houses of Parliament on the riverbank. And then the shape of London – well known to him more because of his study of target maps than because of any memories that the sight evoked – was recognizable.

‘Prepare for action! Open bomb doors!’ He noted the exact time: 2304 hours. At first he was going to advise dropping bombs on the Houses of Parliament, but the briefing clearly said railway stations. There were two right below: Waterloo and Charing Cross. Peter signalled and the captain ordered the first lot of bombs released. There was a series of flashes as they hit, and though Peter could imagine the terror and destruction they had brought, he had no deep feeling of remorse or regret. The British had had every chance to stay out of the war, but they had decided to interfere, and now they must face the consequences.

Crash! The second lot of bombs were striking somewhere south of the river. It was mostly just workers’ housing on that side of the water. The captain should have awaited Peter’s signal, but everyone got excited. There were more explosions, though without any corresponding lights on the ground. He suddenly realized that it was the sound of the British anti-aircraft guns. They were very close, and for the first time on such a war flight Peter felt a little afraid.

At least there were no searchlights here in the very heart of town. The British had concentrated their searchlights to the northeast and along the approaches. They could be seen there now, steadily moving in search of the zeppelins that were behind them. Wait: they were clustering together. They’d caught someone. Two more anti-aircraft shells exploded very close. In the gondola Peter heard the captain order the firing of a red Very pistol light. It was a trick – pretending to be a British fighter plane ordering the guns silent – but the ‘colour of the night’ was changed sometimes hour by hour, and the gunners were not often tricked. The light went arcing out into the darkness, a red firework sinking slowly.

‘Drop water ballast forward!’ murmured the captain, and immediately the orders were given. Peter hung on tight, knowing that the airship would tilt upwards to an alarming angle as she began to rise. There was the whoosh of water rushing through the traps. There she went! The gunfire explosions dropped away below them like the repeated sparking of a cigarette lighter that would not ignite. They continued to rise. Here in the upper air it was dark and cold.

By now a dozen searchlights had fastened on the airship behind them to the north. ‘The Dragon!’ said a whispered voice in the gondola. How could it be the Dragon? She’d been ahead of them. Of course, she was always very slow. Those old engines of hers were the subject of endless grim jokes. They’d been promised new engines again and again, but all the new engines were needed for new airships.

The telephone rang and was answered by Hildmann. ‘Number-two gun position report enemy aircraft,’ he said.

‘Switch off engines!’

The silence came as a sudden shock after so many hours with the throbbing sound of the engines. Everyone throughout the airship remained as quiet as possible and listened.

It was Peter, staring down to the townscape below who spotted him, a large biplane climbing in a wide circle trying to get into position for an attack. The fighters liked to rake the airships from stern to nose, using the new explosive and incendiary bullets. ‘Fighter!’ He pointed.

The captain bit his lip and turned his head to see the instruments. The airship was still at the slightly nose-up angle that provided extra dynamic lift.

Suddenly all was grey: the sky, the ground and all the windows. The zeppelin had passed up into a patch of cloud. Now, with all speed, the airship was ‘weighed off’. The upward movement ended and the airship stopped, engines off and completely silent, shrouded in the grey wet cloud. The mist around them brightened as the searchlight beams raked the cloud’s underside and made the water vapour glow.

They could hear the aeroplane now. It had followed them into the cloud and passed near on the starboard side, its engine faltering as the dampness of the cloud affected the carburettor. It circled once, as if the fighter pilot knew where they were hiding, and then, after another, wider circle, the sound of the plane’s engine grew fainter.

‘Restart engines!’ The clutches were engaged till the props were just turning, treading the air so that the airship scarcely moved. They waited five minutes or more before dropping more water ballast and recommencing their upward movement. Suddenly they were out of the cloud and the stars were overhead. They were very high now and could see a long way. Over northern London clusters of searchlights were still moving slowly across the sky, searching for the airships heading back that way.

Peter provided a course to steer, and slowly – the engines weakened on this thinner air – they headed for home. Everyone was watching the horizon, where the English defences were concentrated. Every few minutes there was a flicker of gunfire, like fireflies on a summer’s evening. That was the gauntlet that they must also run.

‘Look there!’

One by one the searchlights swung over to one point in the sky, forming a pyramid with a silvery shape at its tip. Then the silvery shape went red. At first the red glow was scarcely brighter than the searchlight beams below it. Then it went to a much lighter red, as a cigar tip brightens at a sudden intake of breath.

‘My God!’ Even the captain was moved to cry out aloud. Everyone stared. Flight discipline, rank, was for a moment forgotten. All stared at the terrible sight. None of them had seen such a thing before, except in their nightmares. The stricken airship flared white like a torch, so bright that it blinded them, and they were unable properly to see the dull-red sun into which it changed before dropping earthwards. Then the fiery tangle vanished into a cloud, and the cloud turned pink and boiled like a great furnace.

It was in the silence that followed that the telephone rang. The observation officer – Hildmann – answered tersely. He looked round the control gondola and stared at Peter. If there was a job, then Peter was the one likely to be spared from duties here in the car. The course home was set, and the charts were already folded away, the pencils in their leather case in the rack over the plotting table.

So it was Peter who was sent to speak with the sailmaker. The gas bags were holed; the captain must know how badly. Was it the small punctures that the scout’s machine guns made, or the far more serious jagged tears from shell fragments? Were the leaks low down, or were they in the upper sections of the bags, where a leak meant the loss of all the gas it held? Peter looked around to find an extra scarf and the sheepskin gloves that he’d removed to use the pencils. It would be cold back there inside the envelope, even colder than it was here in the drafty control gondola. He’d found only one glove by the time Hildmann shouted to him again. No matter: he’d keep his hand in his pocket.

He went up the ladder again. It was dark and dangerous picking his way along the keel between the lines of gas bags. It was like walking down the aisle of some echoing cathedral, except that hug silky balloons floated inside and filled the whole nave, from floor to vaulting.

Some of the giant bags were hanging soft and empty. It was here that the sailmaker was already at work, patching the leaks. He called down from the darkness: ‘Herr Leutnant.’ The sailmaker was clinging to the girders high above him. Peter climbed with difficulty. The lack of oxygen made him feel dizzy.

It was while Peter was inspecting the damaged gas bags that the anti-aircraft battery scored its hit. There was a loud bang that echoed in the framework. The airship careened, remained for a moment on its side, so that everything tilted and the half-emptied bags enveloped the two men. Peter fought the silky fabric aside as the airship rolled slowly back and then steadied again. ‘What the devil was that?’ said the sailmaker. Peter didn’t reply, but he knew they were hit and hit badly. It was a miracle that there was no fire. ‘Stay here,’ said Peter. ‘I’ll find out what’s happened.’

When he got back to the control gondola, it was in ruins. The rear portion of the car was gone completely, and a large section of the thin metal floor was missing, so that, still standing on the short communication ladder to the keel, Peter could see the landscape thousands of feet below them. The helmsman and rudder man were nowhere to be seen: the explosion had blown them out into the thin air.

There was broken window celluloid everywhere, and the aluminium girders were bent into curious shapes, like the tendrils of some exotic vine. The body of the captain – hatless to reveal an almost bald head – was sprawled on the floor in the corner, his head slumped on his chest. The observation officer had survived, of course: Hildmann was a tough old bird, the sort of man who always survived. He had somehow scrambled across the two remaining girders and got to the front of the car. He was manning the elevator wheel. When he saw Peter coming down through the hatch, he pointed to the wheel that controlled the rudders and then went back to his task.

‘How bad?’ Hildmann asked him after Peter had swung himself across the gaping hole to take his place at the wheel and steer for home.

‘The gas bags? Two of them are bad, and some of the holes are high. But the sailmaker is a good man, and his assistant is at work, too.’

The observation officer grunted. ‘We can let it go lower, much lower.’ His voice was strained as he gasped for breath. Hildmann was no longer young. At this height the lack of oxygen caused dizziness and headaches and every little exertion seemed exhausting. Peter’s clamber down into the car had made his ears ring, and his pulse was beating at almost twice its normal rate. In the engine cars, and up on the gun positions, men would be suffering nausea and vomiting. It was worth going high to avoid the defences, but today they hadn’t avoided them. ‘A lucky shot,’ said Hildmann, as if reading Peter’s mind.

‘There will be more guns along the coast,’ warned Peter.

‘We must risk that. The gas will be escaping fast at this height; soon we’ll lose altitude whether we want to or not. And the engines will give us more power lower down.’

Peter didn’t answer. Hildmann was deluding himself. The pressure inside the bags would make little difference. Whatever they decided, the airship was continuing to sink, due to the lost hydrogen from the punctured gas cells. Peter was having great difficulty at the helm of the great ship. He had never touched the wheel before; the seamen given this job were carefully chosen and specially trained. Holding the brute, as it wilfully tried to fly its own course through the open sky, was a far harder task than he ever would have believed. He had new respect for the men he’d watched doing it so calmly and effortlessly. And as the thought came to him, he realized that now he would never be able to tell them so: both men had long since hit the ground at terminal velocity, which meant enough force to indent themselves deep into the earth.

‘Is he patching the holes?’ said Hildmann.

‘The sailmaker and his assistant,’ affirmed Peter. ‘They can’t work miracles, though.’