По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

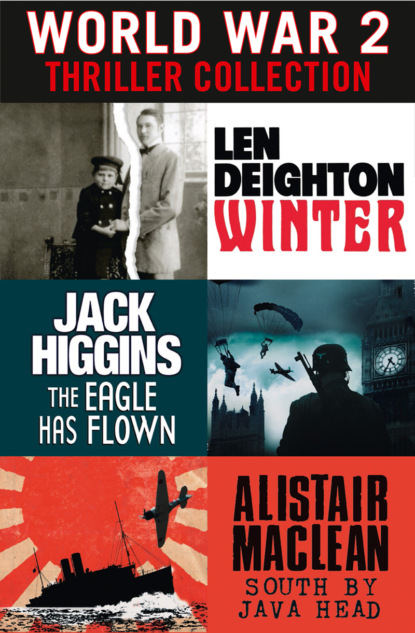

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Stand-to in fifteen minutes.’ At dawn the front-line trenches had to be manned, because it was the best time for the British to attack. But, since the trenches were full of infantry, it was also a good time for the British to strafe them with a barrage of mortar shells.

Alex Horner groped on the floor to find his cigarettes. Together with the matches, he found them in his steel helmet. Unlike most of the soldiers, Alex Horner couldn’t sleep with his helmet on his head. When he’d got his cigarette lit, he tied up the laces of his boots and buttoned up his woollen cardigan, his jacket, and the overcoat in which he’d been sleeping. He moved slowly, as a man does when drunk. Stress, lack of rest, and the stodgy food so lacking in protein made them all a bit robotic.

‘If only the army had not disbanded their airships…’ said Alex. He put some eau de cologne on a dirty handkerchief and wiped his face with it.

‘Well, they have,’ said Pauli, who’d heard Alex’s sad story a hundred or more times.

‘My application was completed and approved. The physical exam would have been no more than a formality. I’m a hundred per cent fit; you know that, Pauli.’

‘I know,’ said Pauli. He couldn’t be too rude to his friend; they both needed someone to complain to. In the absence of any other sympathetic friends they told each other the same stories over and over again.

‘I’d be flying by now.’

‘Perhaps you could transfer to the Naval Airship Division.’

‘They’d never allow that, you know they wouldn’t.’

‘I’ll talk to my brother when I see him. Perhaps he could arrange something for you.’

‘I even bought those books on engine repair and maintenance.’

‘Airships are dangerous. My brother, Peter, was shot down.’

‘You talk to him. Perhaps if I was prepared to go in as a midshipman…’ They both knew that there was no possible chance that he’d be permitted to transfer to the navy, but by common consent they talked of it often.

‘Have you got your pistol belt and the flashlight? It’s time to go, Alex.’

‘It’s the monotony that gets me down. We’ll stand to and freeze for an hour; then we’ll spend ages while the captain inspects every rifle barrel.’

‘Not this morning; this is Easter Saturday. Wake up, Alex! We’re assigned to check the sentries and then be at the old supply line when the wiring party returns.’

Alex nodded, but he didn’t abandon his moaning. ‘Then, when the breakfast is coming, the British will mortar the communication trenches and those fools will drop our breakfast into the mud, the way they did three times last week. On Monday I only got a bread roll and half a cup of coffee.’

‘Don’t you ever think of anything else but food and drink, Alex?’

‘What else is there?’ It was Alex’s ‘morning moan’. Pauli had got used to his friend’s bad moods, which came immediately after waking. In another hour he’d be his normal cheery self again. Until then he needed to moan. ‘I suppose the planes will come over any time now.’

‘It’s too early. The attacks last week were planes coming back from patrol. The English patrol planes go out at dawn and come back about half an hour later. Perhaps the English pilots will stay in bed for Easter.’

‘Where are our planes?’

‘The British believe they must enter our airspace every morning. They say it keeps up their fighting spirit. They send the infantry patrols over to our trenches for the same reason. They are frightened that their soldiers will lose their appetite for the war unless they are sent often to fight us.’

‘Is that what you find out when you speak with the prisoners?’

‘They make no secret of it.’

‘Is Leutnant Brand on duty this morning?’ Alex asked, making the inquiry sound as casual as possible, and yet the imminent encounter with the dreaded Leutnant Brand was uppermost in the thoughts of both young men.

‘Yes, he’s duty officer.’

‘Jesus Christ!’ Alex rubbed his beard again and regretted not shaving, for Leutnant Heinrich Brand was a tyrant, a cruel man who lost no opportunity to make the lives of his junior officers a misery. Brand was thirty-two years old, the son of a baker in a village near the Austrian border. He’d entered the Bavarian cavalry as a boy and risen to the rank of Feldwebel by 1914. It was a rank beyond which he would never have been promoted except for the coming of the war. By the end of December 1914 he was a senior NCO in the regimental training camp. But it was on the Eastern Front, in the fighting of early 1915, that he saved the life of his commanding officer. Attacking Cossacks cut his cavalry regiment to pieces as they retreated through woodland that became marsh and then an open piece of ground that gave the Russian cavalry a chance to demonstrate their superior skill and reckless courage. Brand got the Iron Cross and a commission for that day’s hard fighting. But the same officers who applauded Brand’s bravery did not want to share their mess with this coarse-accented villager, and Brand soon found himself amongst strangers. And this time he was not even in the cavalry.

It was dark and cold, and there was rain in the air. The wind was singing in the massed barbed wire that filled no-man’s-land. As Pauli and Alex plodded their way along the duckboards which made a slatted floor for the deep trench, both were thinking of Brand. The Leutnant saved his particular hatred for these two products of the Prussian army’s most exclusive officer-cadet school. Brand envied them. He would have given almost anything to have the panache, the style and the background – to say nothing of the proper Berlin accent – of the two youngsters.

‘I hate him,’ said Alex Horner as they negotiated the zigzag trenchline, the skirts of their greatcoats heavy with accumulated mud. The sky was clear with a thousand stars and a moon that was almost full and very yellow. The night was bitterly cold. Underfoot the duckboards had frozen hard into the mud, so that they didn’t sink under the boys’ weight the way they usually did in the daytime.

‘Not so loud,’ said Pauli. ‘Voices carry in the middle of the night like this. Last night I could hear the stretcherbearers taking the casualties back to the medical post near Regimental HQ, and that’s a long way away, isn’t it?’

‘What about that Englishman in no-man’s-land last week? Did you hear him sobbing?’

‘I heard him cursing,’ said Pauli. They were both speaking in whispers now as they plodded along the trench.

‘That was later,’ said Alex. ‘That was at the end.’

‘Imagine being out there with a leg shot off. Do you ever think about that, Pauli?’

‘No, I never think about it,’ said Pauli. In fact, like all the rest of them, he found that such ideas haunted his thoughts and gave him nightmares. The shouting and weeping of the mortally wounded Englishman had affected all who heard him. Even Leutnant Brand was heard to curse the dying man.

They reached the first sentry. He was standing on the fire step looking over the parapet. Even the farm boys could look heroic in such a pose, cloaked in a muddy blanket and as still as a statue. ‘Any sign of the wiring party?’ Pauli asked.

‘No, Herr Leutnant,’ the sentry answered without turning his head. Sentries soon learned how dangerous it was to make any sort of movement that might be seen by the British snipers. Twice in the last week snipers had killed sentries. Both times the casualties had been men wearing glasses. It was assumed that the moonlight – or in one case a flare – had glinted on the glass. One of the officers had suggested that men with eyeglasses be excused sentry duty, but in a second-rate unit like this, with so many men from lower medical categories, it would have been an unfair burden on the rest of them.

‘No movement anywhere, Herr Leutnant,’ said the sentry.

It was the same at the next sentry, and the next. But this didn’t mean that there was no one out there in the twisted, tangled chaos of no-man’s-land. The British patrols could move silently and swiftly. They used trench knives and clubs. More than once in the last month a British raiding party had come right over into the German front-line trenches and got out again before the alarm could be sounded. They were trying to get an officer prisoner: that was usually the reason for such raids: an officer prisoner and secret papers that might help their intelligence find the place where the German armies joined, for such a place was an ideal one to attack when the big offensive came.

‘Leutnant Brand should never have sent out a wiring party on a night like this,’ said Pauli. ‘It’s too light.’

‘The wire was broken.’

‘The wire is always broken. It’s murder to send men out to mend it on a night like this.’

They turned the corner and started down the ‘old supply line’. These trenches, captured from the British, were poorly made by German standards. The British infantry always improvised them, with only shallow dugout shelters roofed with corrugated iron sheets and none of the deep dugouts that were standard design when the German engineers constructed their front-line positions. No one liked this section of the front line. Apart from the inferior workmanship, the trench system was all the wrong way round: the old fire steps faced east and there were ‘saps’, bombing sections and machine-gun positions all on the wrong side, so that they were vulnerable to enemy gunfire. Worst of all was the smell. This section of the line was littered with ancient corpses that were integrated into the earthworks.

The much-feared Leutnant Brand was standing on the fire step in order to look across the endless shiny mud of no-man’s-land. He wasn’t using a periscope or the pierced steel that offered some protection. He liked to show how fearless he was: he liked to be thought of as brave to the point of madness. ‘Crazy Heini’, the men called him, and he was proud of that nickname – although he would have severely punished anyone heard using it.

He got down from the fire step. ‘Horner! Winter! You’re both late, you’ll go on report.’ They weren’t late of course – they were three minutes early – but there would be nothing gained from arguing with him. The major would, in any case, believe what Brand told him, or at least the major would pretend to believe it. The major was worn out; he did whatever was easiest, and arguing with Brand was heavy going. Brand knew the regulations word for word – he’d learned them when he was a junior NCO – and now the major had long since learned that he was no match for Brand’s sort of ‘lawyer’s talk’.

‘Young officers should be setting an example to the men,’ said Brand. He always said that, but each time he said it as if it was a new, fresh and original observation that should be carefully noted. ‘Horner! You haven’t shaved. You people think that you are a law unto yourselves. You think a Bavarian regiment isn’t good enough for you Prussians. Well, I’ll have to persuade you it is. And if punishment is the only way, then punishment it shall be!’ Brand did everything he could to speak like a gentleman, but when he got excited his Bavarian accent thickened.

Pauli looked at him. When he’d first heard about this Bavarian sergeant major who’d become an officer on the battlefield, he’d expected to see some red-faced, beer-bellied old fellow with a big nose and a huge moustache. But Brand was younger than the other company commanders, slim-hipped and rather handsome. His nose was thin and bony and his forehead high, with trimmed eyebrows and quick, crazy eyes. His eyes moved all the time, as if he was constantly expecting to be assaulted. When he took off his helmet, as he did when looking through the trench periscope, one could see that his hair was not cropped close to the skull in the way that he insisted all the others under his command had their hair cut. Brand’s hair was of medium length and wavy. Somehow, even here in the front line trenches, he always managed to find ways of keeping clean. He wore a long waterproof coat that he’d got from a British-officer prisoner – ‘trenchcoats’, the British called them – and under it his uniform, complete with Iron Cross medal on his pocket, was relatively clean and dry. In his hand Brand carried a riding crop with which he liked to point at people or things, prod soldiers who needed prodding, or simply slap his thigh reflectively. He slapped his thigh with it now.

‘You’re both going to work hard today, my friends. Winter will go back to the village and bring a burial party up to number-three post. It’s time we got rid of those bodies: it stinks down there.’ Slap, slap, went the riding crop against the skirt of the trenchcoat. He turned to Alex and nodded. ‘Horner! The major wants someone to supervise the detail rebuilding the long dugout. It should have been finished two days ago. Hurry them up. I’ll be along later to see what’s happening.’

Pauli said, ‘I’m going back to Divisional Headquarters today, Herr Leutnant. My brother is coming. The major gave permission.’

‘You’ll do as you’re told, Winter. I want those bodies buried tout de suite.’ Leutnant Brand liked to use French phrases; the officers in his cavalry regiment had all done so.