По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

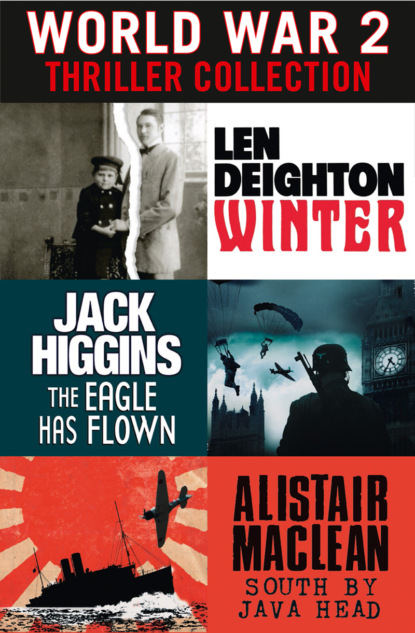

World War 2 Thriller Collection: Winter, The Eagle Has Flown, South by Java Head

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘My brother is coming from Brussels. The major asked the colonel: it’s all official.’

‘The war is official, too,’ said Brand. He was enjoying himself now. He looked at both of them and gave a grim smile, as if inviting them to join in the fun. Then he slapped the skirt of his trenchcoat with the riding crop. ‘Family reunions take place with the commanding officer’s permission, but even then they are subject to the needs of the military situation. I don’t know if your brother is a slack, good-for-nothing nincompoop like you, Winter. He probably is. But unless he is a complete idiot he’ll know that the army comes first. Right, Winter? Understand now, Winter?’

Leutnant Brand was unusually agitated that morning and the reason for this became clear when the Vizefeldwebel came to report that the wiring party had still not returned. Brand went back to surveying no-man’s-land, but this time he used the trench periscope. The sky had gone blood-red and it was getting lighter every minute. If the wiring party – twelve men – were still alive somewhere out in the mud, their chances of surviving through the day were slight. The British would shoot up anything unusual out there; it was the standard practice for both sides. Anything that might be some new sort of weaponry was to be feared, ever since the tanks had appeared last year. And today the weather forecast said the wind was from the west, a light breeze, which would exactly suit the British if they decided on another gas attack. What would happen to the wiring party then? They had gone out wearing the bare minimum of equipment – some without helmets, even – and it was doubtful there would be one gas mask amongst the lot of them.

‘You two, get going!’ said Brand as he remembered that they were still waiting his orders. ‘And don’t let me see you slacking off. Remember what I said: you are going to set an example to the men.’

The Vizefeldwebel watched the exchange with a blank face, but Brand was not willing to let the old man stay out of it. As he watched the two officers hurrying back along the trench, he smiled to show that he was really a good fellow, an ex-Feldwebel who knew that young officers were lazy rogues. But the old man didn’t respond to the smile.

Once Pauli and Alex got back to where the communication trenches started, Pauli said, ‘I so wanted to see my brother. I miss him. It’s nearly a year and he’s come all the way from Brussels.’

‘Just go,’ advised Alex. He knew what the meeting meant to his friend: Pauli had been talking of little else for the last two weeks. ‘The burial party don’t need you to watch them work. They won’t slack on that detail: you can be sure of it. They’ll work to get that stinking job done as quickly as possible.’

‘They’ll need an officer to collect the identity discs from the bodies,’ said Pauli doubtfully.

‘Rubbish!’ said Alex. ‘The NCO will do that. It’s Winkel, a good fellow.’

‘Brand will find out.’

‘How will he find out? Will you tell him? Will I tell him? Winkel won’t make trouble.’

‘He’ll go and check on the burial.’

‘Not Brand. He won’t go near number three until they are all buried. Brand doesn’t like that sort of job. That’s why he always gives them to us to do: it’s the worst thing he can think of to do to us.’

‘I promised Peter….’

‘Go! Go! I told you, go.’

‘I’ll go as far as the village and talk to the NCO in charge of the burial party.’

‘I told you, Winkel is in charge. What are you going to say to him? That you’re frightened of Brand but you are going to disobey him anyway?’

‘I suppose you’re right.’

‘Tell no one. Get the ration truck from the village and go to HQ. Is that where you’re meeting your brother?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, get going. It’s a long walk. I’ll cover for you. I’ll have plenty of opportunities to get away from the party rebuilding the long dugout. It will take them ages yet. You know the way it’s flooding. Only an idiot like Brand would make them persevere with that job.’ He slapped his friend on the arm.

‘Thanks,’ said Pauli. His fears and doubts began to fade as he hurried back along the trench towards Divisional HQ. He decided to consult his brother about dealing with Leutnant Brand. Peter would know how to handle him; Peter knew everything. The more he thought about it the happier he was. The prospect of seeing his brother again filled him with joy.

It was a long way to HQ. To start with, it was just over half a kilometre along communication trenches before the road was reached, but in the drizzling April rain it seemed much farther. At places the trench walls had collapsed and there was a constant movement of men coming the other way. Pauli had to ease his way past ration details and had to wait while reinforcements came through, so it was nearly an hour before the trenches gave way to a sunken road. The road – little more than a track in places – was unseen by even the best positioned of the British artillery observers, and safe from everything except the odd salvo of twenty-five-pounder fire that greeted any dust that was raised at the crossroads. And in this weather there was no dust.

At the crossroads were three military policemen. Two of them were squatting in a dugout shelter roofed with galvanized iron. All three were young, not much older than Pauli. Chains at their collars supported the small metal gorgets that were the badge of their trade and caused their fellow soldiers to call such unpopular men ‘chained dogs’. But theirs was an unenviable job. They were there not only to check the papers of any soldiers leaving the front-line area but also to keep the traffic moving through this place in which the British artillerymen were so interested. Such a task would produce more regular casualties than even the front-line infantry suffered. Pauli felt somewhat better to find that there were more dangerous jobs than his own.

Pauli asked one of the policemen the way. He knew the way, but he still felt nervous about deliberately disobeying Brand’s order, and talking to the military policeman was somehow reassuring. The policeman – a well-fed fellow with a pale, pocked face and a straggling moustache – welcomed a chance to talk. He was not insubordinate, nor was he properly deferential to the difference in rank. Pauli had found this same man to man attitude among some of the men in his regiment, often the older men with families. It was usually the mark of a man who has resigned himself to the inevitability of death.

‘The general found a conspicuous landmark for himself,’ said the military policeman. There was a note of derision in his remark. Conspicuous landmarks were not eagerly sought after in this wartorn terrain. ‘A chateau with two pointed towers …I was on duty there until last month. You’ll see the ruins of a church as you get into the village. Then there’s the officers’ brothel – you’ll see the signs – and then look for the sentries on the right. But it’s a long way yet.’ He didn’t ask to see Pauli’s papers. Pauli wondered if an officer could be shot for such disobedience. With Brand quoting the appropriate rules and regulations, it seemed highly likely. He wished he hadn’t come, but it was too late now.

‘You’ll get a ride on the ration wagon,’ said the policeman. ‘It will be coming back this way. Wait in the shelter, if you want to.’

‘I’ll keep going,’ said Pauli. The other two policemen might not be so negligent about his written orders, or rather, his lack of any.

‘I’m not even German,’ said the policeman. ‘I was born in Vienna.’ It was hardly necessary to say it: the man spoke with a strong nasal, Viennese accent.

‘So was I,’ said Pauli.

‘Really? I wish we were there now, don’t you?’

It was at this point that Pauli felt the policeman’s familiarity had become insubordinate, but even now he didn’t want to upset the fellow. ‘Soon we will be,’ said Pauli.

‘Yes, Herr Leutnant,’ said the policeman. Sensing the young officer’s resentment, he saluted. The rain made his helmet shiny and ran down his face like tears. Of course the man didn’t believe that Pauli had been born in Vienna. Pauli had never had a Viennese accent – although he could mimic one with commendable accuracy. He’d grown up to know the voices of Berlin, and his voice, although not his manner, was that of the Officer Corps.

By the time he started walking again, it was raining heavily. He passed the bloated, rotting corpses of two huge horses. Alongside, a broken wheel stood like a grave marker. The stench was overpowering. Pauli buttoned his overcoat tight against his neck and took off his steel helmet to wipe the sweat from his head and face. To some extent he was sweating with the exertion of his walk, but he felt hot with fear, too.

Only a few hundred yards past the crossroads, he got a ride on the ration wagon that was going back to the depot empty. He sat up beside the driver – a taciturn man, thank goodness – and watched the rain-washed Zeeland horses plod along the ridged track. Their pace was little faster than he’d made on foot, but up here on the driver’s platform was better than picking his way between the submerged potholes and deep mud patches. The landscape was dull, misty and monochrome. There was little movement except for military traffic on the road and a few peasants who, despite everything, clung desperately to their patches of soil.

It was nearly 9:00 a.m. by the time he reached Divisional HQ, situated – as the policeman had promised – in a grand house. There was a large paddock and a dozen magnificent cavalry horses grazing there. They looked at Pauli as he walked past, then went back to their fodder. Clerks were bivouacked in the orchard, and there was a soup kitchen sited in what must once have been a herb garden. Pauli didn’t want to go to the officers’ canteen in case he saw someone from his regiment, so he asked the Feldwebel for something to eat and got a metal cup of hot dried-pea soup with two miserable bits of sausage floating in it. Both soup and sausage were bland and almost tasteless, but it warmed him.

In the grand, marble-paved entrance hall an NCO wearing the smart uniform of a Bavarian rifle regiment was seated at a table. Around him was a constant traffic of messengers, while noisy young staff officers were grouped at the foot of the great staircase. Their voices were not of the sort that Pauli had heard on the parade ground at Lichterfelde; they were the shrill, excited voices of wealthy young aristocrats. The NCO stared at Pauli. Men straight from the battlefield were seldom seen this far behind the lines, and the NCO clerk – who’d not been to the trenches – had never before seen an officer so dirty.

After his inquiries Pauli went up the magnificent staircase and found Peter in an upstairs room talking to an elegant-looking captain. The captain was about forty years old and wore the badges of a heavy cavalry regiment. His striped armband marked him as a staff officer from Corps HQ. Peter and the captain were laughing together as Pauli went into the office and saluted.

Peter! This was the moment he’d risked so much for. This was the meeting he’d waited for so impatiently. Peter! He wanted to throw his arms around his beloved brother and hug him, but that wasn’t something he could do in the presence of a stranger. So he stood anxiously smiling at Peter.

‘So this is the brother?’ said the captain, and both men laughed again. Pauli envied the way his elder brother could make friends so easily. Peter was able to bridge the gap that rank and age created. Peter could even laugh and joke with his father, whereas Pauli was always treated like a baby, both by family and by strangers. Whenever Pauli got away with some misdeed or other, it was always by means of his charm, but Peter talked to other men as an equal, and that was what Pauli so admired. This relaxed and sophisticated elder brother of his would never have endured the bullying of Leutnant Brand; he would have found some way of dealing with him. But God only knows how.

Peter stood up and clasped Pauli’s offered hand. ‘Pauli,’ he said, ‘Pauli.’

Without taking his eyes from his brother for more than a moment, Pauli sat down on a hard wooden chair. It always seemed strange to sit on a proper chair after a long spell in the trenches.

‘I’ll leave you together,’ said the staff officer. ‘There’s not much doing over the Easter weekend. Most of the staff are probably in Brussels on leave.’

The friendly staff officer gave Peter and Pauli the use of the little office room and even sent a soldier to serve them coffee and schnapps.

‘You’re in a terrible state,’ said Peter when they were alone together. He was staring at his younger brother’s dark-ringed eyes and shaved head and at his rain-drenched greatcoat and mud-caked boots. As Pauli loosened his collar, he caught sight of a dirty undervest, too. ‘Haven’t you had time to change into a clean uniform?’ It was the voice of the grown-up brother admonishing the baby about his gravy-stained bib, but Pauli didn’t allow the condescension to spoil things.

For a moment Pauli didn’t reply. He knew, of course, that the civilians didn’t realize that the front line was no more than a filthy ditch from which the sound of bronchial coughing could be heard across no-man’s-land, and where pneumonia was as deadly as enemy bullets and shells. But that his brother should think it was someplace where clean uniforms and pressed linen were available shocked him. ‘There was no time,’ said Pauli. He wished he could take Peter to the trenches and show him what it was like. He’d never understand otherwise. No one could visualize it. It was useless to explain.

‘It’s an officer’s first task to set an example,’ said Peter primly. ‘Surely they taught you that at cadet school.’ Oh, God, how like Leutnant Brand he sounded, thought Pauli. But Peter smiled suddenly and the mood changed. ‘You’ve grown so big, Pauli. So big across the shoulders…’ Was that Peter’s polite way of saying that Pauli had not grown much taller? Pauli had always wanted to be as tall as his brother, ever since he could remember, but now he knew he would never be tall, slim, and elegant: he’d always be short, thickset, broad, and clumsy.

‘You’re promoted,’ said Pauli. Perhaps his elder brother’s shiny new gold ring on that so very clean, neatly pressed naval uniform had gone to his head.

‘Oberleutnants are little more than office boys in Brussels, where I work,’ said Peter. But, in a gesture that belied his modesty, he brushed his sleeve self-consciously as he spoke.

‘You’re looking well, Peter.’ He made no mention of his elder brother’s mutilated hand and tried not to look at it. Peter’s injury frightened him in some way that the firing line did not. Peter was family: an injury to him injured Pauli.