По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

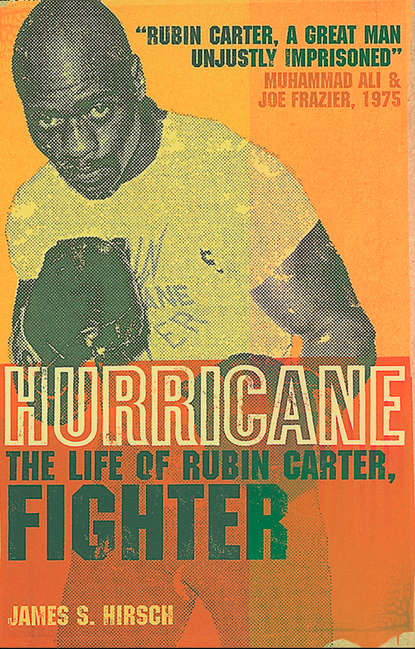

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Carter had committed crimes before, but now he was going to do something far more dangerous. He was going to smuggle guns to the ANC. First, he prowled bars in New Jersey and New York, where hardluck customers traded their guns for drinks and tavern owners ran a second business in arms sales. Carter accumulated four duffel bags for their weapons, then persuaded Johannesburg promoters to set up another fight. This time, his opponent would be an American, Ernie Burford, against whom Carter had split two previous matches. That Carter would travel all the way to South Africa to fight another American made no sense to outsiders, and he told few people about his true motivation, not even Burford. If the South African authorities caught him running guns to the ANC, he would probably never have left the country alive. But the trip turned out to be a great success. He delivered the guns to a grateful Biko, and he knocked out Burford in the eighth round on February 27, 1966.

Eight months later, Carter was arrested for the Lafayette bar murders, and he never heard from Stephen Biko again.

In a few short years, Biko founded the Black Consciousness movement, advocating black pride and empowerment, and he would become one of the most celebrated leaders of black South Africans’ fight against a murderous regime. His activism, however, frequently placed him under police detention, and in 1977 he died from head injuries while under custody, provoking international outrage. He was thirty years old.

(#litres_trial_promo)

After Carter’s loss to Giardello, his boxing career lasted for twenty-two more months. During that period he won 7, lost 7, and had 1 draw. (He ended his career with 28 wins, 11 losses, and 1 draw.) He blamed the losses on increased police and FBI harassment, in New Jersey and elsewhere, and there is credibility to that excuse. The Saturday Evening Post article, which included Carter’s intemperate remarks about the police and his own ruffian past, was published in October 1964. Carter, according to Paterson police records, was arrested twice in the next six months on “disorderly person” charges. (He was found not guilty on one charge and paid a $25 fine on another.) In a sport that requires complete focus, Carter’s concentration was no doubt disturbed by these rising tensions with the law.

But Carter’s own stubbornness hurt him. He worked out with intensity but resisted his trainers. One, Tommy Parks, devised an ingenious double-cross. He began giving Carter “opposite commands.” If he wanted Carter to do roadwork the next morning, he would instruct his fighter to sleep late. Five A.M. would roll around and, sure enough, Carter was ready for roadwork. His footwork needed sharpening? Parks told him to concentrate on his punching. Invariably, Carter followed the “opposite command,” thereby doing exactly what Parks desired.

Carter also lacked discipline. During training, he would get bored at night, sneak out of camp, and go to Trenton or another town to meet women and carouse. He never drank in front of his trainers, but Parks thought he knew when Carter had been tipping the bottle. His skin seemed to grow yellow and his eyes were in soft focus. Carter once had a sparring match in Newark with a tough but unaccomplished fighter named Joe Louis Adair. Carter had been drinking the previous night, and he was sluggish in the ring. Adair knocked him down in the first round, and a newspaper published a story about the Hurricane’s improbable pummeling. “Rubin was a Mike Tyson with heart,” Parks said in an interview years later. “But drinking was the bane of his career.” Carter, asked about that assessment, agreed.

Parks specialized in working with troubled kids, but he was removed as Carter’s trainer in 1963 because the boxer’s manager wanted a white trainer to improve Carter’s marketability on television. But the change hurt in the ring. Carter preferred black trainers like Parks and said his subsequent white trainers varied in effectiveness. His own effectiveness may also have been diminished because he stopped scaring opponents. His invincible armor, once cracked, gave his competitors more confidence. Carter’s image and tenacity still made him a crowd favorite, though, and at the end of 1965 he was ranked fifth among middleweights by Ring

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: