По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

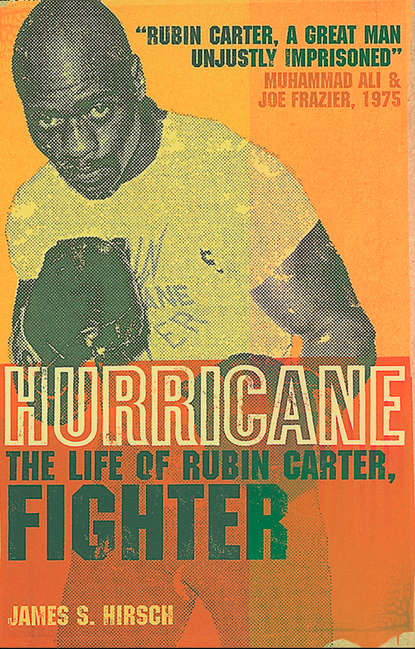

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

This time Bradley spoke. “That Negro right there.”

That Negro, indeed. The dividing line of this trial had been clearly drawn, and it cut along race. The prosecutor and his staff were white. The investigators and police officers were white. The judge was white. The victims were white. Their family and friends in the courtroom were white. The state’s witnesses were white. The jury, save one man, was white. The courtroom clerk was white. The courthouse guards were white, and the courthouse attendees were white. Rubin Carter was black, bald, and bearded. His co-defendant was black. His lawyer was black. His alibi witnesses were black. His family and friends who crowded the courtroom were black. Could a white juror look at that contrasting tableau and not be affected? Carter feared not. He believed that once a juror is called to serve the government, he takes on the mantle of the government. The juror is now part of a famous case. He is now part of the system, and he is going to do what the system wants. In Carter’s mind, the juror thinks: Maybe the government didn’t prove it, but they must know something. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be here.

Carter kept his feelings about race to himself. In fact, he surprised both Brown and John Artis’s lawyer, Arnold Stein, by not complaining of racial prejudice. “With Bello and Bradley, I’d say, ‘Fuck these white sons-of-bitches,’” Brown recalled many years later. “Carter would say, ‘They’re sons of bitches,’ but he wouldn’t say they were white. To this day, I’ve never heard him say a racial epithet.”

Carter and Artis both testified. Carter gave the same account of his whereabouts on the night of the murder that he had already given the police and grand jury. He took the stand wearing the same clothing he had worn that night, including his cream sport coat. Patricia Graham Valentine had testified that she saw two well-dressed Negroes in dark clothes fleeing the bar.

After two and a half weeks of testimony, Ray Brown, in his closing argument, shambled over to the jury box and made clear what he thought this trial was all about: race. He started slowly, noting that the jurors needed to be guided by reason, “not passion, not prejudice, not bias. Reason. Reason. Reason.” He ticked off Carter’s alibi witnesses, who said they were around him between two and two-thirty on the night of the crime, then he reared back and lit into Bello and Bradley. He reminded the jury of the witnesses’ criminal records and that Bello in particular offered testimony that contradicted his previous statements. Is it not reasonable, Brown said, to assume that Bello “is testifying for hope, for favor?” He called Bello and Bradley “jackals” and “ghouls,” said the judge had prevented him from implying that they were responsible for the murders, but “I will imply with all my might” that they were somehow involved.

“Remember what [Bradley] said. It will remain with me forever for a special reason. I remember … he said, ‘That Negro over there.’ What is that, an animal? Well, I will tell you, in his voice it was there, and everything around this case revolves around that simple fact. They were Negro …”

Brown told the jury that his client had lived since 1957 “without a blemish” and that he “is now a human being standing in fear of his life … Can you believe that this man who did not run, who did not hide, did this, did these things? How can you believe this …?” Almost three hours into his summation, Brown reiterated that Carter did not fit the description of the killers; then, exhausted and with tears in his eyes, he closed by denouncing the courtroom proceeding and the city of Paterson.

“This is probably the last place in the entire world where a trial like this could go on,” he said. “Where else would they tolerate three weeks of picking a jury? Where else would they tolerate lawyers sometimes bumbling, sometimes stumbling? … Where else would they tolerate this in the world, where else but here? Why then must this man suffer because he rode the streets of Paterson, minding his own business, a black man driving a white car? I know you won’t stand for it. Thank you.”

The courtroom was stirred by Brown’s stem-winding broadside—muffled sniffles, angry voices—although the jurors sat with stone faces. After the lunch recess, Vince Hull made his methodical summation in a monotone, shoring up maligned witnesses and reconciling contradictions in testimony. Marins could not be held accountable for failing to identify the defendants at the hospital, Hull said, because he was under sedation. The prosecutor acknowledged that financial rewards were offered in June of 1966 to anyone who helped the police solve the crime, but if Bello and Bradley were testifying for money, why did they wait until October? While Hull lacked the drama of Ray Brown, he was able to turn the weaknesses of his case into apparent strengths. For example, the testimony of Bello and Bradley revealed numerous contradictions in their accounts of what happened that night. Bello said he saw three people driving by in a white car. Bradley said he saw four people. Bradley said he saw the car going west on Lafayette Street. Bello saw the car on Sixteenth Street. These and other inconsistencies only proved one thing, Hull said, that these witnesses had to be telling the truth! Lying witnesses would have been more coordinated. “If they were so interested in the reward,” Hull asked, “why didn’t they get their stories straight?”

Hull proved himself a master rhetorician. For example, several character witnesses for John Artis, including Robert Douglas, his pastor, testified that the defendant was a nonviolent, honest young man. Given that no motive was adduced, the jurors might very well doubt that a peaceful, law-abiding kid would brutally kill three people without any provocation. Hull’s response: The character witnesses did not know their man. “What weight can their testimony have as to [Artis] being law-abiding and nonviolent after hearing all of the testimony as to what transpired in and around the Lafayette Grill on the morning of June 17, 1966.” This sophistry bewildered Artis. Hull discredited his character witnesses by citing the very crime that his character witnesses said he was incapable of committing.

Hull finished his summation with a bit of high theater.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, when you retire to the jury room, all of the exhibits in this case that have been admitted in evidence will be in there with you, including this bullet, this .32 S&W long Remington Peters. That will be one of the items that goes into the jury room with you, and after you deliberate upon the facts in this case, and weigh all of them carefully, that bullet, small in size, will get larger and larger and larger, and that bullet will call out to you and say to you, Bello and Bradley told the truth. That bullet will call out to you and say to you that Carter and Artis lied, and that bullet will get louder and larger and it will cry out to you like three voices from the dead, and it will say to you Rubin Carter and John Artis are guilty of murder in the first degree …”

Hull then emptied out three bags of bloody clothes on a table in front of the jury, each bag’s contents in a separate pile. Beside each heap he placed a picture of the decedent whose clothes they were, the photos showing each person laid out on slabs in the morgue.

“There once was a man,” the prosecutor continued, “a human being by the name of James Oliver, a bartender at the Lafayette Grill, and he wore this shirt, and he looked like this when he was placed into eternity by a 12-gauge shotgun shell. There once was a man, a fellow human being by the name of Fred Nauyoks who lived in Cedar Grove, and he had the misfortune of going to the Lafayette Grill on June 16–17, 1966, and this is how his life ended when he was murdered in cold blood with a .32-caliber bullet through his brain. And there once was a human being, a woman by the name of Hazel Tanis, and she wore these clothes, these bullet-riddled clothes, when she was shot, not once, not twice, not three times—four times; two of the bullets passed through her and two remained in her body, and she clung on to life for nearly a month, and on July 14 of 1966 she passed away, and this is what became of this fellow human being.

“Ladies and gentlemen, on the question of punishment, the facts of this case clearly indicate that on the morning of June the seventeenth of 1966, the defendants, Rubin Carter and John Artis, forfeited their rights to live, and the State asks that you extend to them the same measure of mercy that they extended to James Oliver, Fred Nauyoks, and Hazel Tanis, and that you return verdicts of murder in the first degree on all the charges without a recommendation. Thank you.”

The following day, May 26, 1967, Judge Larner gave the jurors lengthy instructions, advising them that they had to return with a unanimous verdict. He also pointed out that “the race of the defendants is of no significance in this case except as it may be pertinent to the problem of identification.” Finally, he turned to a woman who had been seated at a desk beside him throughout the trial. “All right. You may proceed, Miss Clerk.” The woman got up and started to spin the wooden lottery box that held the names of the fourteen jurors. Carter frantically tugged Ray Brown’s coat sleeve.

“What the hell is she doing?” Carter hissed into his ear. “Get her away from that damn box.”

“Shh, Rubin,” Brown whispered back. “She’s only picking the twelve jurors who will decide the verdict. Two of the fourteen will have to go.”

With a sweep of her hand, the clerk pulled the West Indian’s name out of the box, leaving an all-white jury to decide the defendants’ fate. It did not take long. The jurors deliberated for less than two hours, then returned to the courtroom, which quickly filled with spectators and reporters. Court officers searched the purses of entering women to guard against smuggled weapons. There were wild rumors that Carter’s allies, in the event of a guilty verdict, would try to break him out. City detectives, plainclothes policemen, and uniformed officers from the county Sheriff’s Department circled the room and lined the building’s corridors. Outside, patrolmen were on alert that a guilty verdict could trigger riots in the street.

In the courtroom, the four women jurors had tears in their eyes. The others took their seats with bowed heads. Rubin Carter, John Artis, and their lawyers rose from their seats. A hush fell over the room as the jury foreman, Cornelius Sullivan, announced the verdict: “Guilty on all three counts.” After a long pause he continued: “And recommend life imprisonment.”

Carter’s head dropped, but he showed no emotion. Artis’s legs buckled, and he clenched a fist. The stunned silence of the courtroom was suddenly pierced by a scream from Carter’s wife, her prolonged wails sending a dagger into Rubin’s heart and alarming seasoned court observers. “She let out a scream the likes of which I’ve never heard before or since,” said Paul Alberta, a local reporter, many years later. “It was the kind of scream of someone being physically tortured.”

Tee thought the trial would have a Perry Mason ending: a defense attorney would spin around, point to a member of the gallery, and identify the true killer. Now she collapsed to the floor, unconscious; a friend and three attendees carried her limp body out of the room. Judge Larner asked that the jurors be polled to be sure that they agreed with the verdict. Each one announced: “I agree.” One juror, a short, elderly woman with gray hair and glasses, looked at Carter on her way out. “I feel nothing for him,” she said, then pointed to Artis, “but I feel so sorry for him.”

The summer of 1967 was the worst of the decade’s “red hot summers.” From April through August, violence raged in 128 cities from Jersey City to Omaha, from Nashville to Phoenix. The most destructive conflagrations erupted in Newark, where 26 people were killed, and Detroit, where 43 perished. In all, 164 disorders resulted in 83 deaths, 1,900 injuries, and property damage totaling hundreds of millions of dollars.

But Paterson remained calm. The convictions of Rubin Carter and John Artis brought to a close the worst crime in the city’s history. Judge Larner, noting Carter’s “antisocial behavior in past years,” sentenced him to three life sentences, two consecutive and one concurrent. Artis, as a first-time offender, received three concurrent life sentences. The only thing that surprised Carter was that the jury did not recommend the electric chair. Why would a white jury spare the life of two black men found guilty of such a barbaric act? Mercy? Shit! They’ve fried niggers for less. Maybe the jury felt pity for Artis and thus spared them both from the chair. Maybe the jury had doubts about their guilt. It didn’t matter—not now, not ever. One lie covers the world, Carter thought, before truth can get its boots on.

(#ulink_16f13498-1a12-51cb-abf7-01eb94ad2783) Even with Carter in jail, Wegner lost to the reform candidate, Lawrence Kramer.

(#ulink_4d288e5b-b4c1-5776-bb50-621aae8c35c6) In a letter to Governor Richard Hughes in 1968, F. Lee Bailey, who represented Matzner, wrote: “I have never, in any state or federal court, seen abuses of justice, legal ethics, and constitutional rights such as this case has involved.”

5 (#ulink_92092e32-004c-5ab2-9788-a13105e90bc1)

FORCE OF NATURE (#ulink_92092e32-004c-5ab2-9788-a13105e90bc1)

TRENTON STATE PRISON did not tolerate dissidents. The gray maximum-security monolith ran according to an intractable set of rules that completely controlled its captives’ lives. Prison guards often said: “The state always wins,” meaning, rebellious prisoners ultimately comply. Rubin Carter would test that motto unlike any other inmate in New Jersey’s history. But opposition to authority was nothing new for him. It was, in fact, his nature.

Born on May 6, 1937, in the Passaic County town of Delawanna, Carter learned early on that the men in his family are not intimidated by threats. His father was one of thirteen brothers who all grew up on a cotton farm in Georgia. According to family lore, one brother, Marshall, was once seen fraternizing with a white woman. Panic surged through the house as word arrived that the Ku Klux Klan planned to crash the Carter home. The boys’ father, Thomas Carter, sent several of his sons to Philadelphia, instructing them to return with fifteen guns—one for each member of the family. The Klan arrived, but the Carters, fortified with weapons, stood their ground, and the hooded riders retreated. Shortly thereafter, the family packed up and moved to New Jersey—although each brother would return to Georgia to select a bride.

The Klan story, no doubt embellished over the years, impressed on Rubin the importance of family pride and unity. His father, Lloyd, also regaled his seven children with stories of tobacco-chewing crackers in the South hunting down black men, then tarring or hanging them. On cold nights at home, Lloyd Carter told these stories around a coal-stoked burner as his children ate roasted peanuts sent by relatives in the South. Rubin, in stocking feet, would stretch his legs toward the crackling stove and let his mind race through the Georgia swamps, chased by whooping rednecks and howling dogs. The specter scared him, but he felt protected by the closeness of his family.

When Rubin was six, the Carters moved to Paterson, to a stable, racially mixed neighborhood known as “up the hill”—a few blocks away from poorer residents, who were literally “down the hill.” Lloyd Carter made good money with his various business enterprises. He traded in for a new car every two or three years, and the Carters were the first black family in the neighborhood to own a television. But working two jobs six days a week—Sundays were for praying—wore him down, and his wife, Bertha, worried about his health. A lean, strong, bespectacled man just under six feet tall, Lloyd defended himself by quoting the Holy Scriptures. “Bert,” he said, “‘whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.’”

Lloyd Carter also disciplined his children with a religious zeal. A deacon in his Baptist church, he forbade the children from playing records or cards at home. Listening to the radio or dancing in the house was also prohibited. While he spoke softly, he carried a hard switch, and Rubin gave his father ample reason to use it.

The boy’s penchant for fighting often earned him swift punishment, but Rubin felt he had good reason to fight. He stuttered severely, stomping his foot on the ground to push the words out, and bitterly fought any kid who teased him for this impediment. His father had stammered as a youth, and his father had struck him with a calf’s kidney to try to cure him. Somehow Lloyd did overcome his speech problem, but he didn’t give his son much help. On the contrary, Rubin’s parents believed an old wives’ tale that severe stuttering indicated that the speaker was lying, which meant Rubin seemed unable to tell the truth. His response was to avoid talking, but that fueled the perception that he was stupid. To compensate for his stumbling tongue, the boy excelled in physical activities. He was muscular, fast, and fearless, and he saw himself as a protector of other people, particularly his siblings.

His brother Jimmy, for example, was two years older than Rubin, but he was studious, quiet, and prone to illness. When the Carters lived in Delawanna, Jimmy was sent to the basement to fetch coal from the family bin, but a neighborhood bully who was stealing the coal beat him up in the process. With his parents off at work, Rubin went to the basement himself to avenge the Carter name. It was his first fight. As he later wrote:

A shiver of fierce pleasure ran through me. It was not spiritual, this thing that I felt, but a physical sensation in the pit of my stomach that kept shooting upward through every nerve until I could clamp my teeth on it. Every time Bully made a wrong turn, I was right there to plant my fist in his mouth. After a few minutes of this treatment, the cellar became too hot for Bully to handle, and he made it out the door, smoking.

Bullies were not the only victims of Rubin’s wrath. In a Paterson grammar school, he once looked out his classroom door and saw a male teacher chasing his younger sister Rosalie down the hall. He raced out the door, tackled the teacher, and began swinging. The school expelled Rubin, prompting his father to beat him with a belt. But the beatings at home did not deter the boy, who continued to lash out at most anyone, even a black preacher who lived in the neighborhood. He owned a two-family home, and when he saw Rubin, at the age of ten, flirting with a girl who also lived in the house, he shooed him off the porch. But Rubin punched back with all his strength. The dazed preacher reported the incident to Rubin’s father, who stripped his son, tied him up, and whipped him.

Lloyd Carter feared that his son’s pugnacity would cost him his life one day, specifically at the hands of whites, and that fear led to a searing childhood incident. Each summer, Lloyd and his brothers drove their families in a caravan from New Jersey to Georgia, where they stayed with relatives, worked on farms, told stories, and sang and prayed together. On one occasion after church, some cotton farmers gathered in a grove to sing and picnic. A white man selling ice cream bars stopped nearby, and children carrying dimes raced to get a treat. Rubin had barely torn his wrapper when his father landed a heavy blow on his face, sending Rubin and the ice cream in opposite directions. Lloyd Carter never said why he struck his son; years later Rubin realized that his father feared white men, and he wanted his son to feel that same fright as well. Instead, the nine-year-old, his face puffed and bruised, came away with a very different lesson. He had taken his father’s best shot, and now he no longer feared the man. Moreover, Rubin determined that he was never going to let another person hurt him again. Not his father, not a police officer, not a prison guard, not a mayor, not a bum. Nobody.

Young Rubin welcomed any physical challenge—the more dangerous, the better. He swam in the swift waters of the Passaic River, jumped off half-built structures at construction sites, ran down mountains, and rode surly mules on his grandfather’s farm. On a swing set in the Newman playground, he swung so high that he flipped completely around in full circles. On one occasion, he and a friend, Ernest Hutchinson, were cutting through a backyard when a big bulldog ran at them. “I was going nuts, but Rubin told me to stand behind him,” Hutchinson recalled. “All of the sudden, the dog leaps and—bam!—Rubin hits him right in the chest. The dog rolled over and couldn’t catch his breath. I’ll never forget that. We were ten years old.”

Rubin continued to rebel against his father’s rules. Even on a simple walk to P.S. 6 on Carroll and Hamilton Streets in Paterson, he had to make his own way. Lloyd Carter stood on the porch of their Twelfth Avenue home and made sure all his children took the safest, most direct route. When the brood was out of his sight, Rubin ducked into an alley, hopped a fence, and took a different, longer way. He was literally incapable of following the crowd.

But misdeeds landed him in more serious trouble—with both his father and ultimately the police. Rubin stole vegetables from a garden owned by one of his father’s co-workers, ransacked parking meters, and led a neighborhood gang called the Apaches. When he was nine, the Apaches crashed a downtown marketplace, stealing shirts and sweaters from open racks, then fleeing to the hills. Rubin gave his stolen goods to his siblings. When his father saw the new clothes, price tags still attached, and was told that Rubin was responsible, he beat his son with a leather strap, then called the police. The boy was taken to headquarters—his first encounter with the police. He would always resent that his father had initiated what would become a lifelong battle with law enforcement officials. The following day, the Child Guidance Bureau placed him on two years’ probation for petty larceny.

For all the confrontations between father and son, Rubin noticed that he liked to do many of the same things as his father. While his two brothers and four sisters often begged off, Rubin hunted with his father and accompanied him on trips to the family farm in Monroeville, New Jersey. His mother told him that his father was hard on him because Lloyd himself had also been a rebel in his younger days. Now, the father saw himself in his youngest son.

That did not become clear to Rubin until he was in his twenties, when he and his father went to a bar in Paterson where the city’s best pool shooters played. As they walked in, the elder Carter quipped, “You can’t shoot pool.”

A challenge had been issued. Rubin considered himself an expert player, and he had never seen his father with a cue stick. Indeed, Lloyd hadn’t been on a table in twenty years. They played, betting a dollar a game, and Lloyd cleaned out his son’s wallet.

Rubin, shocked, simply watched. “Where did you learn to play?” he asked.

“How do you think I supported our family during the Depression?” his father replied. “I had to hustle.”

Unknown to his children, Lloyd Carter had been a pool shark, and his disclosure seemed to clear the air between him and Rubin. “Why do you think I always beat on you?” Lloyd said later that night. “You wouldn’t believe how many times your mother said, ‘Stop beating that boy, stop beating that boy.’ But I saw me in you.” Lloyd Carter had also rebelled against authority, and he knew that was a dangerous trait for a black man in America. “I was trying to get that out of you,” he told his son, “before it got hardened inside.”

It was too late, however. Rubin’s defiant core had already stiffened and solidified.

For all the turmoil in his youth, Carter actually fulfilled one of his boyhood dreams: he wanted to join the Army and become a paratrooper. In World War II the Airborne had pioneered the use of paratroopers in battle. It was not, however, the division’s legendary assaults behind enemy lines that captivated Carter. Nor was it the Airborne’s famed esprit de corps or its reputation for having the most daring men in the armed forces. Carter liked the uniforms. Even as a boy he had a keen eye for sharp clothing, and he admired the young men from Paterson who returned home wearing their snappy Airborne outfits: the regimental ropes, the jauntily creased cap, the sterling silver parachutist wings on the chest, the pant legs buoyantly fluffed out over spit-shined boots.

By the time Carter enlisted, however, the uniform was not his incentive. At seventeen, Carter escaped from Jamesburg State Home for Boys, where he had been serving a sentence for cutting a man with a bottle and stealing his watch. On the night of July 1, 1954, Carter and two confederates fled by breaking a window. They ran through dense woods, along dusty roads, and on hard pavement, evading farm dogs, briar patches, and highway patrol cars. Carter’s destination was Paterson, more than forty miles away. When he reached home, the soles on his shoes had worn off. His father retrofitted a fruit truck he owned with blankets, and Rubin hunkered down in the pulpy hideaway while detectives vainly searched the house for him. Soon Carter was shipped off to relatives in Philadelphia. He decided, ironically, that the best way for him to hide from the New Jersey law enforcement authorities was by joining the federal government—the armed forces. With his birth certificate in hand, he told a recruiting officer that he was born in New Jersey but had lived his whole life in Philly. No one ever checked, and Rubin Carter, teenage fugitive, was sent to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, to learn to fight for his country.