По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

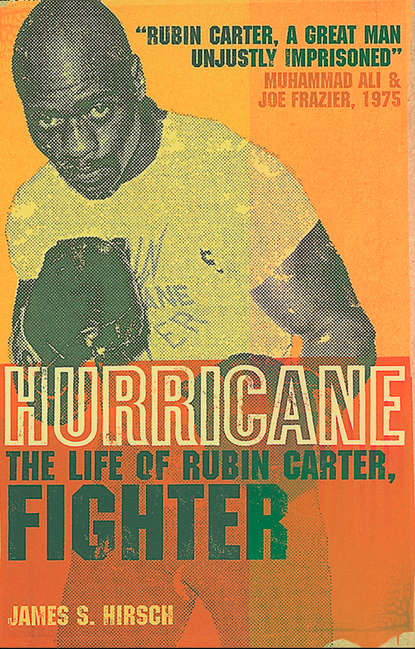

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Carter shrugged off the incident. Unknown to him, a police radio call had gone out a short while earlier indicating that a white car with “two colored males” had left a shooting scene at the Lafayette Grill. Capter and DeChellis had spotted a white car followed by a black car speeding out of Paterson. The officers gave chase, jumping on Route 4 heading toward New York, but they never saw the cars again. So they had returned to Paterson when they saw and stopped Carter’s car.

Artis drove on to Carter’s house, where Carter went inside, collected about $100, and told Tee he was going back out. The trio returned to the Nite Spot, which was closing down, so Carter instructed Artis to drive to Club LaPetite, on Bridge Street, to look for Hardney. But they discovered that that club too had closed; after sitting in the car for a few minutes, Artis and Royster decided to call it a night.

Artis, who was still driving, dropped off Royster on Hamilton Street sometime after 3 A.M. With Carter now in the front seat, he continued down Hamilton, then turned right at East Eighteenth Street. At the intersection of East Eighteenth and Broadway, Artis put on his right blinker and waited for the signal to change. Suddenly, a patrol car came screeching behind them. The cop hurriedly said something into his car radio, opened his car door, and hustled over to the bewildered Artis and Carter. Then they recognized Sergeant Capter again.

“Awww, shit, Hurricane, I didn’t realize it was—” But before he could finish, four other squealing police cars arrived at the intersection. Someone else took charge and as Capter stepped away, Carter made eye contact with him and said, “Aw, fuck!” Other officers, their guns pulled, circled the Dodge. “Get out of that car,” barked one cop. “No, stay in the car,” another yelled. After a few more moments of confusion, an officer looked at Artis and pointed in the opposite direction on East Eighteenth Street. “Follow that car,” he yelled.

“What car?” Artis asked. But there was no time to talk. The sirens went off and the police cars began to peel away. Artis turned the car around and the cavalcade began racing up East Eighteenth. Artis had never been arrested and had never had any trouble with the police. Now he looked into his rearview mirror and saw a cop leaning out the window of the car behind them, pointing a shotgun at him. Artis felt his testicles tighten. “Damn, Rubin, damn! What’s going on?” he yelled.

Carter was also petrified. He had no idea where they were heading, only that they had turned East Eighteenth Street into the crazy backstretch of a stock car race. He saw landmarks fly by. There was a cousin’s home on the corner of East Eighteenth and Twelfth Avenue. There was the Nite Spot on the corner of East Eighteenth and Governor. But then the juggernaut sped beyond the black neighborhoods into unknown territory. Finally, the lead police car slowed down and made a sharp left turn at Lafayette Street, five blocks north of the Nite Spot. A crowd of people in the brightly lit intersection scattered as the pacer car screeched to a halt. The other vehicles followed suit.

Everything seemed to be in miniature. The streets were so narrow, the intersection so compressed, that any car whipping around a corner could easily crash into an apartment building or a warehouse. “What the fuck are we doing here?” Carter blurted. Neither he nor Artis had ever been inside the Lafayette bar; Carter had never even heard of the place. These are not my digs, but whatever went down, it had to be bad.

A scene of chaos lay before them. An ambulance had pulled up next to the bar, where a bloodstained body was being hauled out on a stretcher beneath the neon tavern sign. The throng of mostly white bystanders, many in pajamas, robes, or housecoats, milled about the Dodge, parked on Lafayette Street and hemmed in by police cars. There was panicked crying and breathless cursing, the slap of slamming car doors, and the errant static of police radios. Whirling police lights gave the neighborhood’s old brick buildings a garish red light as about twenty white cops, wearing stiff-brimmed caps, shields on their left breast, and bullet-lined belts, whispered urgently among one another.

The neighbors, some weeping, began to converge on the Dodge. Peering into the open windows, they looked at the two black men with anger and suspicion. Carter and Artis both sat frozen, unclear why they had been brought there but fearing for their lives. This is how a black man in the South must feel when a white mob is about to lynch him, Carter thought, and the law is going to turn its head. Finally, a grim police officer approached Artis.

“Get out of the car.”

“Do you want me to take the keys out?”

“Leave the keys.”

Then another officer intervened. “Bring the keys and open the trunk!”

“No problem,” Artis said.

As Artis headed to the rear of the car, Carter hesitated. If I get out of this car, it could be the worst mistake I’ve ever made. Artis opened the trunk, and a cop rummaged through Carter’s boxing gloves, shoes, headgear, and gym bag.

Another officer motioned to Carter to step out. Carter opened the door, but he had held his tongue long enough. “What the hell did you bring us here for, man?”

“Shut up,” the officer shouted as he cocked the pistol. “Just get up against the wall and shut up, and don’t move until I tell you to.”

As Carter and Artis walked toward the bar at the corner of Lafayette and East Eighteenth, a hush settled over the crowd. With bystanders forming a semicircle around the two men, Carter and Artis stood facing a yellow wall bathed in the glare from headlights. Artis turned his right shoulder and searched for a familiar face, maybe someone from racially mixed Central High School, his alma mater, but he saw only white strangers. The police frisked them brusquely but found nothing on them or in Carter’s car or trunk. Another ambulance arrived, and Artis felt the hair on his neck rise when he saw another body, draped in a white sheet, roll past him on a stretcher.

Finally, a paddy wagon pulled up and someone shouted, “Get in!” Carter and Artis stepped inside and were whisked away. Sitting by themselves, the two men were once again speeding through Paterson, heading to the police headquarters downtown. No one had asked them any questions or accused them of anything. They could see the driver through a screen divider but were otherwise isolated. “Something terrible is going on, but what’s it got to do with us?” Artis asked.

Carter, disgusted, told him to stay calm. “Don’t volunteer anything, but if someone asks you any questions, tell them the truth. The cops are just playing with me, as usual. It’ll all be cleared up soon.”

The paddy wagon stopped downtown, and the doors swung open at police headquarters. Built in 1902 after a devastating fire wiped out much of Paterson, the building is a hulking Victorian structure with dark oak desks and wide stairways. But Carter and Artis had barely gotten inside when there was another commotion. “Get back in!” someone shouted, and the two men returned to the wagon, which peeled off again. Now they headed on a beeline south on Main Street, eventually stopping at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Paterson’s oldest, where plainclothes detectives were waiting. Carter and Artis were hustled out of the truck and into the emergency room. Everything seemed white, the walls and curtains, the patients’ gowns and nurses’ uniforms, the floor tile and bedsheets. The room had that doomy hospital smell of ether and bedpans and disinfectant. The only patient was a balding white man lying on a gurney, a bloody bandage around his head, an intravenous tube rising from his arm, and a doctor working at his side.

“Can he talk?” asked one of the detectives, Sergeant Robert Callahan.

The doctor, annoyed at the intrusion, shot a disapproving glance at the detective, then at Carter and Artis. “He can talk, but only for a moment.” The doctor lifted the lacerated head of William Marins, shot in the Lafayette bar. The bullet had exited near his left eye, which was now an open, serrated cut. He was pallid and weak.

“Can you see clearly?” Callahan asked the one-eyed man. “Can you make out these two men’s faces?”

Marins nodded his head feebly. Callahan pointed to Artis. “Go over and stand next to the bed.” Artis walked over.

“Is this the man who shot you?” Callahan asked.

Marins paused, then slowly shook his head from side to side. Callahan then motioned for Carter to step forward. “What about him?”

Again, Marins shook his head.

“But, sir, are you sure these are not the men?” Callahan asked in a harder voice. “Look carefully now.”

Carter had been relieved when the injured man seemed to clear him and Artis. But now he concluded the police were going to do whatever they could to pin this shooting on them. Previous assault charges against Carter had been dismissed. Police surveillance had yielded little. Now, this: pell-mell excursions through the night, an angry mob outside a strange bar, a one-eyed man lying in agony, and Carter an inexplicable suspect. He had had enough. As Marins continued to shake his head, Carter closed his eyes, clenched his fists, and spilled his boiling rage. “Dirty sonofabitch!” he yelled. “Dirty motherfucker!”

Back at police headquarters, in the detective bureau, Carter found himself in a windowless interrogation room. It was familiar ground. He had been questioned in the same room twenty years earlier for stealing clothing at an outdoor market. (His father had turned him in.) Two battered metal chairs and a table sat beneath a cracked, dirty ceiling. Artis was left to stew in a separate room, which had green walls, a naked light bulb, and a one-way mirror in the door. Artis could see, between the door and the floor, the black rubber soles of the officers outside his door. He knew they were watching him.

Both men lingered in their separate rooms for several hours, their alcoholic buzz long worn off. They simply felt exhaustion. At around 11 A.M., the door to Carter’s room opened and Lieutenant Vincent DeSimone, Jr., walked in. The two men had a history. DeSimone joined the Paterson Police Department in 1947 and had been one of the officers who questioned the teenage Carter after he assaulted the man at the swimming hole. DeSimone was a coarse and intimidating old-school cop, who would quip about suspects, “He’s so crooked, they’ll have to bury him standing up.” A relentless interrogator, he was known for his ability to elicit confessions through threats and promises. He would do anything for a confession, including pulling out a string of rosary beads to bestir a guilty conscience. He hated the 1966 Miranda decision, in which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that no confession can be used against a criminal defendant who was not advised of his rights. The ruling, DeSimone feared, gave confessed criminals a loophole.

(#ulink_02605922-d695-559c-a964-5d37f8dd80cf)

In the 1950s he joined the Passaic County Prosecutor’s Office as a detective specializing in homicides, and he was known for keeping index cards in his pocket so he wouldn’t have to carry a notebook. His bosses viewed him as the finest law enforcement official in the state, their own Javert, and his power and reputation were unquestioned.

But on the streets of Paterson’s black community, DeSimone had a different reputation entirely, for he embodied the racist, bullying tactics of an overbearing police force. His confessions had less to do with gumshoe police work than with intimidation, and he was feared. Frankly, he looked scary. In World War II he had taken a grenade blast in the face, and despite several surgeries, his jowly visage was disfigured. A scar inched across his upper lip, which was pulled tightly back, and drool sometimes gathered at the side of his mouth. He had thick eyeglasses, spoke in a gravelly voice, and wore an open sport jacket across his thick, hard gut, revealing his low-slung holster.

DeSimone was tense when he entered Carter’s holding room. He had been awakened at 6 A.M. with news of the shooting, and he stopped off at the crime scene before going to the police station. Despite his many years in police work, this was his first interrogation for a multiple homicide.

“I’m Lieutenant DeSimone, Rubin. You know me.” He sat down heavily and pulled out his pen and paper.

“You can answer these questions or not,” he continued. “That’s strictly up to you. But I’m going to record whatever you say. Just remember this. There’s a dark cloud hanging over your head, and I think it would be wise for you to clear it up.”

“You’re the only dark cloud hanging over my head,” Carter said.

DeSimone was joined by two or three other officers. Over the next couple of hours, Carter recounted his whereabouts on the previous night, from the time he left his home after watching the James Brown special to his two encounters with Sergeant Capter. He mentioned his trip to Annabelle Chandler’s and various club stops. When DeSimone finally told Carter that four people had been shot, Carter waved off the suspicion: “I don’t use guns, I use my fists. How many times have you arrested me around here for using my fists? I don’t use guns.”

Carter was certain the interrogation was just another example of police harassment for his bellicose reputation. He felt his position on fighting was well known to DeSimone and the other officers: he would fight only if provoked. He did not imagine that even an old antagonist like DeSimone would consider him a suspect for killing people inside a bar he had never entered.

During the questioning, DeSimone shuttled back and forth between Carter and Artis in parallel interrogations. It was more difficult to write down the answers from Artis, who spoke faster. DeSimone also told Artis that “there was a dark cloud hanging over you,” but he said the young man had a way out. “When two people commit a murder, you know who gets the short end of the stick? The guy who doesn’t have a record, and you don’t have a record. That’s the guy they really stick it to. Tell us what you know.”

“I don’t know anything,” Artis said.

By midday Carter’s wife heard he had been picked up, and she came to the station.

“Do you want me to call a lawyer?” Tee asked.

“What do I need a lawyer for?” Carter responded. “I didn’t do anything, so I’ll be out of here shortly.”

Later, while Carter was heading to the bathroom, he was taken past several witnesses who supposedly saw the assailants fleeing the crime scene. One was Alfred Bello, a squat, chunky former convict who was outside the bar when the police arrived. He told police at the crime scene that he had seen two gunmen, “one colored male … thin build, five foot eleven inches. Second colored male, thin build, five foot eleven inches.” Another was Patricia Graham, a thin, angular brunette who lived on the second floor above the bar and said she saw two black men in sport coats run from the bar after the shooting and drive off in a white car. Both Bello and Graham would later provide critical testimony in the state’s case against Carter, giving different accounts from those in their initial statements.

A police officer asked the group of witnesses if they recognized Carter. “Yeah, he’s the prizefighter,” someone said. Asked if he had been spotted fleeing the crime scene, the witness shook his head.

After DeSimone completed his questioning of Carter, he gathered up his papers. “That’s good enough for the time being, but there’s one thing more that I’d like to ask. Would you be willing to submit to a lie detector test?”

“And a paraffin test, too,” Carter said without hesitation. “But not if any of these cops down here are going to give it to me. You get somebody else who knows what he’s doing.”