По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

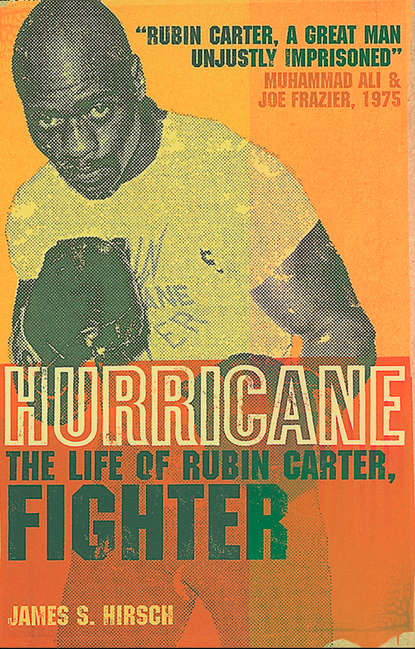

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Outside prison, vodka was Carter’s drink of choice. Straight up, on the rocks, in a plastic cup, in a glass, from a bottle, it didn’t matter; it just had to be vodka. He was not a binge drinker but a slow, relentless sipper, and he could drink a fifth of vodka in a single night. Carter stayed clear of the bottle, mostly, when in training, but when he was out of camp, he kept at least one bottle of 100-proof Smirnoff’s in his car; friends hitching a ride got free drinks.

Carter concealed his drinking as much as possible. It was a sign of weakness and undermined his image as an athletic demigod. To avoid drinking in clubs, he picked up liquor in stores and drank in his car, sometimes with drinking buddies, sometimes alone. He tried not to order more than one drink at any one club on a given night. His wife rarely saw him imbibe and had no idea of the scope of his addiction. He carried Certs and peppermint candies to mask the alcohol on his breath, and he never got staggering drunk.

While Carter was a dedicated night owl, he was also a celebrity loner whose ready scowl stirred fear in bystanders, and he shunned close personal ties. He was often silent and moody, and many blacks in Paterson viewed him with a mixture of respect, envy, and fear. “Everybody loved Rubin, but no one was his friend,” said Tariq Darby, a heavyweight boxer from New Jersey in the 1960s. “I remember seeing him once in that black and silver Cadillac. He just turned and gave me that nasty look.”

Tensions were more overt between Carter and Paterson’s white majority as he flaunted his success in ways that he knew would tweak the establishment. He owned a twenty-six-foot fishing boat with a double Chrysler engine, which was docked at a marina in central New Jersey. He owned a horse, a once-wild mare he named Bitch, and rode in flamboyant style on Garrett Mountain. Dressed in a fringed jean jacket, a ten-gallon hat, and spur-tipped boots, Carter was hard to miss passing the white families picnicking on the hillside, and he didn’t mind when his riding partner was a white woman.

Carter’s shaved head, at least twenty-five years before bald pates became a common fashion statement among African Americans, had its own political edge. In the early 1960s, many blacks used lye-based chemical processors to straighten their curls and make their hair look “white.” White was cool. But Carter’s coal-black cupola sent a message: he had no interest in emulating white people. In fact, he shaved his head in part to mimic another glabrous black boxer, Jack Johnson, who won the heavyweight title in 1908 but was reviled as an insolent parvenu who drove fancy cars, drank expensive wines through straws, consorted with white women, and defied the establishment.

Carter’s showy displays jarred white Patersonians, who had a very different model for how a black professional athlete should act. They cherished Larry Doby, a hometown hero and baseball pioneer. On July 5, 1947, Doby joined the Cleveland Indians, breaking the color barrier in the American League. He was the second black major league player, following Jackie Robinson by eleven weeks. This feat spoke well of Doby’s hometown, Paterson, and Doby seemed to always speak well of the city. Never mind that Doby, who grew up literally on the wrong side of the Susquehanna Railroad tracks, knew well the racism of Paterson. As a kid going to a movie or vaudeville show at the Majestic Theater, he had to sit in the third balcony, known as “nigger heaven,” and he could not walk through white sections of Paterson at night without being stopped by police. Even after he became a baseball star, Doby was thwarted by real estate brokers from buying a home in the fashionable East Side of Paterson. He eventually moved his family to an integrated neighborhood in the more enlightened New Jersey city of Montclair.

But in public Doby was always a paragon of humility and deference. After he helped the Indians win the World Series in 1948, he was feted in Paterson with a motorcade. A crowd of three thousand gathered at Bauerle Field in front of Eastside High School, his alma mater, and city dignitaries gave effusive speeches about a black man whose deeds brought glory to their town. Then Doby took the microphone: he thanked the mayor and his teachers and coaches, concluding with these words: “I know I’m not a perfect gentleman, but I always try to be one.”

No white authority figure in Paterson ever called Rubin Carter a gentleman, perfect or otherwise. He was viewed not simply as brash and disrespectful but as a threat. Bad enough that he could knock down a horse with a single punch. Carter also owned guns, lots of them—shotguns, rifles, and pistols. He learned to shoot as a boy, practicing on a south New Jersey farm owned by his grandfather, and he honed his skills as a paratrooper for the 11th Airborne in the U.S. Army. He used his guns mostly for target practice but also for hunting, roaming the New Jersey woodlands with his father’s coon dogs. Carter could nail a treebound raccoon right between the eyes. He also owned guns for protection, and he had some of his suits tailored wide around the breast to accommodate a holster and pistol, which he would wear when he feared for his safety.

Like Malcolm X, Carter advocated that blacks use whatever means necessary, including violence, to protect themselves. He participated in the March on Washington in 1963, but two years later he rebuffed Martin Luther King, Jr.’s request to join a demonstration in Selma, Alabama. Carter knew he would not, could not, sit idly in the face of brutal attacks from law enforcement officials, white supremacists, or snarling dogs. “No, I can’t go down there,” he told King. “That would be foolishness at the risk of suicide. Those people would kill me dead.”

Carter did not accept the mainstream civil rights approach of passive resistance. He believed the sacrifices that blacks were making, whether on the riot-torn streets of Harlem or in the bombed-out churches of Birmingham, were unacceptable. Malcolm X had been killed. So too had James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, three young civil rights workers, Medgar Evers, a black civil rights leader, and others unknown. Nonviolence is Gandhi’s principle, but Gandhi does not know the enemy, Carter thought.

When under attack, Rubin Carter believed in fighting back; in his view it was the police who were usually doing the attacking. But his many scrapes with the cops, plus some intemperate comments to a reporter, gave the authorities reason to believe that he was able, even likely, to commit a heinous crime.

In addition to the assault and robbery conviction in 1957, Carter, at fourteen, and three other boys attacked a Paterson man at a swimming hole called Tubbs near Passaic Falls. The man was cut with a soda water bottle and his $55 watch was stolen. Carter was sentenced to the Jamesburg State Home for Boys, but he escaped two years later. In the 1960s, his fracases with the police were common. In one incident, on January 16, 1964, a white officer picked him up after his Eldorado had broken down on a highway next to a meatpacking factory near Hackensack, New Jersey. He was driven to the town’s police headquarters, then accused of burglarizing the factory during the night. He had been locked in a holding cell for four hours when a black officer arrived and recognized him. “Is that you in there, Carter? What the hell did you get busted for, man?” Carter let out a stream of invective about the cops’ oppressive behavior. He was finally released after the black officer demanded to know the grounds on which he was being held. According to the official record, Carter had been arrested as a “disorderly person” for his “failure to give good account,” and the charge against him was dismissed.

Hostilities between Carter and the police, in New Jersey and elsewhere, escalated to a whole other level after a Saturday Evening Post article was published in October 1964. The story was a curtain raiser for the upcoming middleweight championship fight between the challenger, Carter, and Joey Giardello, the champ. The article, which introduced Carter to many nonboxing fans, was headlined “A Match Made in the Jungle.” Actually, the bout was to take place in Las Vegas, but “Jungle” referred to Carter’s feral nature. He was described as sporting a “Mongol-style mustache” and appearing like a “combination of bop musician and Genghis Khan.” With Carter fighting for the crown, “once again the sick sport of boxing seems to have taken a turn for the worse,” the article intoned. Giardello, photographed playfully holding his two young children, was the consummate family man. Carter sat alone, staring pitilessly into the camera.

In his interview with the sportswriter Milton Gross, Carter raged against white cops’ occupying black neighborhoods in a summer of unrest, and he exhorted blacks to defend themselves, even if it meant fighting to their death. He told the reporter that blacks were living in a dream world if they thought equality was around the corner, that reality was trigger-happy cops and redneck judges.

That part of the interview, however, was left out of the article. Instead, Gross printed his reckless tirade so that it was Carter, not the police, who looked liked the terrorist. Describing his life before he became a prizefighter, Carter told the writer: “We used to get up and put our guns in our pockets like you put your wallet in your pocket. Then we go out in the streets and start shooting—anybody, everybody. We used to shoot folks.”

“Shoot at folks?” Carter was asked, because this seemed too much to believe and too much for Carter to confess even years later.

“Just what I said,” he repeated. “Shoot at people. Sometimes just to shoot at ’em, sometimes to hit ’em, sometimes to kill ’em. My family was saying I’m still a bum. If I got the name, I play the game.”

This was sheer bluster on Carter’s part—no one had ever accused him of shooting anyone—but it was how he tried to rattle his boxing opponents and shake up white journalists. He invented a childhood knifing attack “I stabbed him everywhere but the bottom of his feet”—and the story quoted a friend of Carter’s who recounted a conversation with the boxer following a riot in Harlem that summer. The uprising occurred after an off-duty police lieutenant, responding to a confrontation between a sharp-tongued building superintendent and black youths carrying a bottle, shot to death a fifteen-year-old boy. Carter, according to his friend, said: “Let’s get guns and go up there and get us some of those police. I know I can get four or five before they get me. How many can you get?”

This fulsome remark sealed his image for the police and now for a much larger public. On the Friday-night fights, the showcase for boxing in America, Carter stalked across television screens throughout the country as the ruthless face of black militancy. He was seen as an ignoble savage, a stylized brute, an “uppity nigger.” He was out of control and, more than ever, he was a targeted man. (He was also not to be the champion. The Giardello fight, rescheduled for December in Philadelphia, went fifteen rounds; Carter lost a controversial split decision.)

After the Saturday Evening Post article appeared, authorities in Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, Akron, and elsewhere approached Carter when he was in town for a fight. On the grounds that he was a former convict, they demanded that he be fingerprinted and photographed for their files. At the time, the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s clandestine political arm, COINTELPRO (for “counter intelligence program”), was spying on Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and other civil rights leaders. Carter believed that by 1965, the FBI had begun tracking him, which simply made him more defiant.

(#ulink_77a76ef1-92da-5236-a539-a93d0ef1e35c) In the summer of 1965, for example, Carter arrived in Los Angeles several weeks early for a fight against Luis Rodriguez. The city’s police chief, William Parker, soon called Carter in his motel on Olympia Boulevard and told him to get down to headquarters.

“So, you thought you were sneaking into town on me, huh?” Parker said. “But we knew you were coming, boy. The FBI had you pegged every step of the way.”

“No, I wasn’t trying to sneak into your town. I just got here a little bit early,” Carter said. A woman whom Carter had seen tailing him at the airport and his motel was standing in the office. He motioned her way, then looked back at the police chief. “My God,” he said. “She’s got a beautiful ass on her, ain’t she?”

By June 1966, Carter’s last prizefight had been more than three months earlier in Toledo, against the Olympic gold medalist Wilbert “Skeeter” McClure. The match ended in a draw. He feared he faced increased police surveillance and harassment as black militancy became a greater force across America. Instead of young people marching together arm-in-arm and singing “We Shall Overcome,” new images emerged of combative black men and women wearing black berets and carrying guns, their fists raised in defiance. Social justice was not enough. Black separatism and empowerment were part of the new agenda. Malcolm X’s legacy was being carried on by charismatic leaders like Stokely Carmichael and Bobby Seale, whose cries for “black power” galvanized growing numbers of disaffected black youths while igniting a backlash from frightened whites. Paterson swirled with rumors that black organizers had come from Chicago to reignite the protests that had ripped the city apart two summers earlier.

Rubin Carter knew he needed to get off the streets.

Carter had a match coming up in Argentina in August, and he was moving to his training camp on Monday, June 20. Camp itself was a small sheep farm in Chatham, New Jersey, run by a man from India named Eshan. On Thursday the sixteenth, beneath a warm afternoon sun, Carter filled the trunk of his white 1966 Dodge Polara with boxing equipment. He could almost feel the canvas under his feet, and he was grateful.

In the evening his wife made dinner for her husband and their two-year-old daughter, Theodora. Mae Thelma, known as Tee, looked like a starlet, with dark chocolate skin, a radiant smile, and arched eyebrows. She sometimes tinted her hair with a bewitching silver streak. She was also quiet and self-conscious. As a young girl in Saluda, South Carolina, Tee had crawled into an open fireplace, disfiguring several fingers on her left hand. Thereafter she often wore long white gloves to conceal her scars, or she kept her hand in her coat pocket and slipped it under tables, sometimes awkwardly, at clubs or restaurants. Rubin had dated her for months before he finally caught a glimpse of the injury. On their next date, he pulled off to the side of the road, took her left hand, and pulled off her glove. “Is this what you’ve been hiding from me all this time?” he asked. “Do you think I would love you any less?”

When Tee told him she was pregnant, she feared he would abandon her; she herself had grown up in a fatherless home. Instead, Rubin promptly proposed, and they were wed on June 15, 1963. Carter families, Rubin knew, did not go without fathers, and their children did not go on welfare. Theodora was born seven months later. Rubin and Tee had an unspoken agreement: Rubin took care of his business, and Tee took care of Rubin. They each had their own friends and socialized separately. Tee never watched any of Rubin’s fights. Some nights, when they ended up at the same club, the people around them often didn’t know they were married.

This deception gave rise to some pranks. One night, sitting at the opposite end of the bar from his wife, Carter asked a bartender, “Would you please send down a drink to that young lady and tell her I said she sure looks pretty.”

The unsuspecting bartender walked down to Tee. “This drink comes from that gentleman up there, and he says you sure look pretty.”

She wrinkled her nose at Rubin. “Tell him I think he looks good too.”

The flirtation ended with Tee’s accepting Rubin’s offer to go home with him, leaving the bartender in awe of this Lothario’s good luck.

The couple’s three-story home, in a racially mixed neighborhood in Paterson, was comfortably decorated with a blondish wood dining room table, blue sofas with gold trim, African artifacts hanging on the walls, and an oil painting of the family. On the night of June 16, Carter watched a James Brown concert on television, doing a few jigs in the living room with Theodora. During the commercials, he repaired to the bedroom to dress for the night and returned to the living room with a new ensemble in place. Black slacks. White dress shirt. Black tie. Black vest. A cream sport jacket with thin green and brown stripes. Black socks. Black shoes. A splash of cologne, and a dab of Vaseline on his cleanly shaven head.

That night Carter decided to drive the white Polara, which was blocking the Eldorado in the garage. (He leased the Polara as a business car for the tax writeoff.) It was a warm evening, and Carter, at the outset, had business on his mind. He had a midnight meeting with his personal adviser, Nathan Sermond, at Club LaPetite to discuss the Argentina fight; the promoters were balking at giving Carter a sparring partner in Buenos Aires. Carter was also to meet, at the Nite Spot, one of his sparring partners, “Wild Bill” Hardney, who would be joining him in camp the following week. But by 11 P.M., the night was taking some unusual twists.

Sipping vodka outside the Nite Spot with a group of people, Carter bumped into a former sparring partner, Neil Morrison, known as Mobile for his Alabama roots. Carter had been looking for him for months because he suspected him of stealing three of his guns from his Chatham training camp. The theft—of a .22 Winchester, a bolt-action .22 rifle, and a 12-gauge pump shotgun—had occurred the previous fall when Morrison was staying in the camp. Morrison, dressed in dungarees and a white T-shirt, had just been released from prison, and Carter confronted him, accusing him of stealing the guns.

“Man, you know I would never do that,” Morrison said.

“I know a person who’s seen you with my guns,” Carter said. A childhood friend, Annabelle Chandler, had told Carter she saw Morrison with the weapons.

“The hell you do!” Morrison said.

Carter, Morrison, and two other Nite Spot regulars agreed to drive over to Chandler’s apartment, in the nearby Christopher Columbus Projects. There they found Chandler in the bathroom, sick. She had recently returned from the hospital and was suffering from cancer. Carter entered the bathroom and told her he had brought Morrison with him so she could repeat how she saw him with Carter’s guns.

“If I had known you were going to tell him, I wouldn’t have told you,” she told Carter.

“Well, forget about it,” he said in deference to her illness. Carter dropped the matter; his guns had been stolen and sold and lost forever. The group returned to the Nite Spot. Little did Carter know that in years to come, this chance encounter with Neil Morrison and quick jaunt to a run-down housing project to visit a dying woman would be used against him in a devastating way.

The night was unusual for another reason. Word had spread that Roy Holloway, the black owner of the Waltz Inn, had been slain by a white man, Frank Conforti. When the police arrested Conforti, a crowd of people, mostly blacks but not including Carter, angrily yelled at the white assailant. Holloway’s stepson, Eddie Rawls, was the bartender at the Nite Spot, and he pulled up to the club when Carter was in the midst of his dispute with Morrison. Carter expressed his condolences to Rawls, who was coming from the hospital. The group chatted for several minutes before Rawls went inside the club.

There was a buzz at the Nite Spot and other black clubs about a “shaking,” or retaliation of some sort, for the Holloway murder. Carter, however, had never met Holloway and was never heard to express any anger over the murder. He had other things on his mind. Thursdays were known as “potwashers night.” Domestics were given the night off, and the women got into the Nite Spot for free through the back door. By 2 A.M., as the crowd began to thin out at the Nite Spot, Carter was still looking for a date. When last call was announced, he approached the bar and asked for the usual, a vodka. He took out his wallet, but when he discovered it was empty, he told the bartender he’d have to pay up later.

Carter had planned to go to an after-hours social club, so he had to head home to get some money. He spotted his sparring partner, “Wild Bill” Hardney, and asked if he would go with him so Tee would not complain about his going out again. But Hardney, preoccupied with his girlfriend, begged off.

Then Carter noticed John Artis on the dance floor. The former high school football and track star was a sleek, high-spirited dancer who practiced his steps at home, following the advice of one of his uncles: “When you dance, be original and be different from the others. Take a step and change it, and always be smooth.”

Nineteen-year-old Artis loved fast cars and pretty girls, and that night, dressed in a sky-blue mohair sweater with a JAA monogram, matching light blue sharkskin pants, and gold loafers, he was certainly on the prowl. But it had been a long boozy evening—he had been sick earlier—and he was winding down. He had just performed a dazzling boogaloo when Carter called out to him. “Nice moves, buddy,” he said. “Wanna take a ride?” Overhearing the conversation was John “Bucks” Royster, a balding alcoholic drifter who was friendly with Carter. Royster, figuring drinks would be available in the car, asked if he could join them. Outside, Carter flipped Artis the keys and asked him to drive. Then Carter climbed in the back seat, slumped down, and called out directions to his house, about three miles southeast of the Nite Spot.

Artis had only met Carter a couple of times. He rambled on about how boxing was not his favorite sport, but his friends would be impressed when they heard he’d been driving Hurricane’s car, even if it wasn’t the Eldorado. There was talk about women they knew, who was looking fine and who wasn’t, and other idle conversation. Their chatter came to a quick end at 2:40 A.M. when the Polara crossed Broadway and a police car, lights flashing, pulled up next to it. A policeman motioned Artis to stop about six blocks north of Carter’s house.

Artis pulled out his license as Sergeant Theodore Capter, flashlight in hand, approached the car. A second officer, Angelo DeChellis, walked behind the car and wrote down the license number, New York 5Z4 741. Artis handed over his driver’s license but couldn’t find the registration. “It’s on the steering post, John,” Carter said as he sat up in the back. Carter was relieved when he saw Capter, a short, graying officer who had been on the force for eighteen years and had always gotten along with him. “Hey, how you doing, Hurricane?” Capter asked, flashing his light in the back. “When’s your next fight?”

“Soon,” Carter said. “But what’s wrong? Why did you stop us?”

“Oh, nothing, really. We’re just looking for a white car with two Negroes in it. But you’re okay. Take care of yourself.”