По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

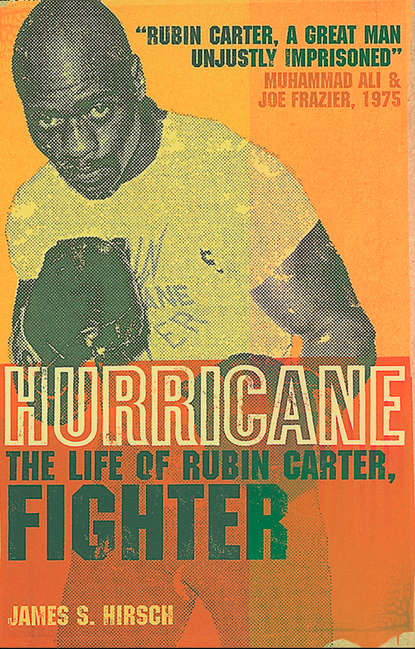

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At 2:30 P.M., Sergeant John J. McGuire, a polygraph examiner from the Elizabeth Police Department, met Carter in a separate room. A barrel-chested man with short hair, McGuire had just been told about the shootings, and he was in no mood for small talk. “Carter, let me tell you something before you sit down and take this test,” he said in a tight voice. “If you have anything to hide that you don’t want me to know, then don’t take it, because this machine is going to tell me about it. And if I find anything indicating that you had anything to do with the killing of those people, I’m going to make sure your ass burns to a bacon rind.”

“Fuck you, man, and give me the goddamn thing.”

McGuire wrapped a wired strap around Carter’s chest, and Carter put his fingers in tiny suction cups. He answered a series of yes-or-no questions and returned to his holding room. After another delay, McGuire showed up and laid out a series of charts tracking his responses. DeSimone and several other officers were there as well. Pointing to the lines on the chart, McGuire declared, “He didn’t participate in these crimes, but he may know who was involved.”

“Is that so?” DeSimone asked.

“No, but I can find out for you,” Carter said.

Sixteen hours after they had been stopped by the police, Carter and Artis were released from the police station. Carter was given his car keys and went to the police garage, only to find that the car’s paneling, dashboard, and seats had been ripped out. The following day, June 18, Assistant County Prosecutor Vincent E. Hull told the Paterson Morning Call that Carter had never been a suspect. Eleven days later Carter, as well as Artis, testified before a Passaic County grand jury about the Lafayette bar murders. DeSimone testified that both men passed their lie detector tests and that neither man fit the description of the gunmen. Notwithstanding the adage that a prosecutor can indict a ham sandwich—prosecutors are given a wide berth to introduce evidence to show probable cause—the prosecutor in the Lafayette bar murders failed to indict anyone. Carter traveled to Argentina and lost his fight against Rocky Rivero. The promoter never did give him a sparring partner. The thought flashed through Carter’s head that he should just stay in Argentina, which had no extradition treaty with the United States. That way, the Paterson police would no longer be able to hassle him. Instead he returned home.

On October 14, 1966, Carter was picked up by the police and charged with the Lafayette bar murders.

(#ulink_a2df9932-a034-526f-abc1-81e25fbd65aa) FBI files released through the Freedom of Information Act indicate that Carter was under investigation at least by 1967. The report could not be read in full because the FBI had blacked out many sections, evidently to protect its informants.

(#ulink_61c3e3d4-af24-5860-a5e6-a7103fad4c12) The Miranda decision had been issued only days before the Lafayette bar murders. DeSimone testified that he gave Carter his Miranda warning, which Carter denies.

4 (#ulink_072ea2af-f2c4-5a67-b461-c2ee983e9e78)

MYSTERY WITNESS (#ulink_072ea2af-f2c4-5a67-b461-c2ee983e9e78)

IT WAS THE BREAK everyone had been waiting for. On October 14, 1966, the front page of the Paterson Evening News screamed the headline: “Mystery Witness in Triple Slaying Under Heavy Guard.” A three-column photograph, titled “Early Morning Sentinels,” showed tense police officers in front of the Alexander Hamilton Hotel on Church Street guarding the “mystery witness.” An unnamed hotel employee said he saw the police hustle a “short man” into an elevator the day before at 6 P.M. The elevator stopped on the fifth floor, where a red-haired woman was seen peering out from behind a raised shade.

The newspaper story raised as many questions as it answered, but the high drama indicated that a breakthrough had occurred in the notorious Lafayette bar murders, now four months old. Excitement swirled around the Hamilton, where a patrol car was parked in front with two officers inside, shotguns at the ready. Roaming behind the hotel were seven more officers, guarding the rear entrance. A police spotlight held a bright beam on an adjoining building’s fire escape, lest an intruder use it to gain access to the Hamilton. Two more shotguntoting cops stood inside the rear entrance, and detectives roamed the lobby. Overseeing the security measures, according to the newspaper, was Mayor Frank Graves.

John Artis saw the headline and thought nothing of it. He assumed he had been cleared of any suspicion of the Lafayette bar shooting after he testified before the grand jury in June and no indictments had been issued. At the time, Artis was at a crossroads in his own life. His mother had died from a kidney ailment a month after he graduated from Central High School in 1964. Mary Eleanor Artis was only forty-four years old, and her death had devastated John, an only child. He knocked around Paterson for several years, working as a truck driver and living with his father on Tyler Street. In high school, he had been a solid student and a star in two sports, track and football, and he sang in the choir at the New Christian Missionary Baptist Church. He had giddy dreams of playing wide receiver for the New York Titans (later known as the New York Jets). He also had a bad habit of driving fast and reckless—he banged up no fewer than eight cars—but he had no criminal record and never had any problems with the police. Neither of his parents had gone to college, and they desperately wanted their only child to go. By the fall of 1966, Artis had been notified by the Army that he had been drafted to serve in Vietnam, but he was trying to avoid service by winning a track scholarship to Adams State College in Alamosa, Colorado, where his high school track coach had connections.

On October 14, dusk had settled by the time Artis finished work. It was Friday, the night before his twentieth birthday, and an evening of dancing and partying lay ahead. He stopped at a dry cleaner’s to pick up some shirts, then went into Laramie’s liquor store on Tyler Street to buy an orange soda and a bag of chips. He and his father lived above the store. As he was paying for the soda, the door of the liquor store swung open. “Freeze, Artis!” a cop yelled. “You’re under arrest!”

Artis saw two shotguns and a handgun pointed at him. “For what?” he demanded.

“For the Lafayette bar murders!”

“Get outta here!”

Police bullying of blacks in Paterson was so common that Artis thought this was more of the same, an ugly prank. But then two officers began patting him down around his stomach and back pockets. Artis handed his clean shirts to the liquor store clerk and told him to take them to his father. His wrists were then cuffed behind his back. Damn, Artis thought, these guys are serious! On his way out of Laramie’s, Artis yelled his father’s name: “JOHHHHN ARTIS!” As he was shoved into a police car, Artis saw his father’s stricken face appear in the second-story window.

Rubin Carter was at Club LaPetite when one of Artis’s girlfriends approached him with the news: John had been arrested.

“For what?” Carter asked.

“I don’t know, they just arrested him.”

Like Artis, Carter had seen the “Mystery Witness” headline in the newspaper but hadn’t given it a second thought, and he didn’t connect the headline to Artis’s arrest. Carter, distrustful of the police, feared for Artis’s safety, so he got into his Eldorado and drove to police headquarters to check up on the young man. As he neared the station, he put his foot on the brake; then, out of nowhere, detectives on foot and in unmarked cars swarmed around his car.

“Don’t move! Put your hands on the wheel! Don’t move!”

Here we go again, was all Carter could think. But this police encounter proved to be much more harrowing than his June confrontation. His hands were quickly cuffed behind his back, and he was shoved into the back seat of an unmarked detective’s car. According to Carter, the officers did not tell him why they had stopped him or what he was being charged with. Instead, with detectives on either side of him, the car doors slammed shut and the vehicle sped away, followed by several other unmarked cars. Carter had no idea where they were going, or why. Soon the caravan headed up Garrett Mountain, cruising past the evergreens and maple trees. Even at night Carter knew the winding roads because he often rode his horse on the mountain. The motorcade finally came to a stop along a dark road, and there they sat. Detectives holding their shotguns milled around, and Carter heard the crackling of the car radios and officers speaking in code. They did not ask him any questions. Damn! They’re going to kill me. They sat for at least an hour, then Carter heard on the car radio: “Okay, bring him in.” He always assumed that someone had talked the detectives out of shooting him.

At headquarters, Carter was met by Lieutenant DeSimone and by Assistant County Prosecutor Vincent E. Hull. It was Hull who spoke: “We are arresting you for the murders of the Lafayette bar shooting. You have the right to remain silent …” The time was 2:45 A.M. Unknown to Carter, Artis had also been taken to Garrett Mountain, held for more than an hour, then returned to headquarters and arrested for the murders. The Evening News said the arrests “capped a cloak-and-dagger maneuver masterminded by Mayor Graves,” who grandly praised his police department: “Our young, aggressive, hard-working department brought [the case] to its present conclusion.”

Some nettlesome questions remained. Though the police searched the city’s gutters and fields and dragged the Passaic River, they never found the murder weapons. The authorities were also not divulging why Carter and Artis killed three people. Robbery had already been ruled out, and the Evening News reported on October 16 that the police had determined there was no connection between the Roy Holloway murder and the Lafayette bar shooting. Such details were unimportant. The Morning News rejoiced at the arrest, trumpeting on the same day that the newspaper “exclusively broke the news that the four-month-old tavern murders were solved.”

Carter figured his arrest was tied to the November elections. Mayor Graves, prohibited by law from running for a fourth consecutive term, was hoping to hand the job over to his chosen successor, John Wegner. What better way to show that the city was under control than by solving the most heinous crime in its history? After the election, Carter reckoned he’d be set free.

(#ulink_67d02a48-eccb-59c6-9f87-e61e2e3c8b63)

But sitting in the Passaic County Jail, where each day he was served jelly sandwiches, Carter learned through the jailhouse grapevine that two hostile witnesses had emerged. Alfred Bello, the former con who had been at headquarters following the crime, and Arthur Dexter Bradley, another career criminal, were near the Lafayette bar trying to rob a warehouse on the night of the murders. Questioned by the police that night, Bello said he could not identify the assailants. But suddenly his memory had improved. Both Bello and Bradley now told police that they had witnessed Carter and Artis fleeing the crime scene.

The Passaic County Prosecutor’s Office took the case to a special grand jury empaneled in the basement of the YMCA, convened to investigate the sensational killing of a young housewife named Judy Kavanaugh. On November 30, Carter heard a radio report on the loudspeakers in jail that the grand jury had indicted Kavanaugh’s husband for the murder. Paul Kavanaugh was in a cell near Carter’s. Then, almost as an afterthought, the announcer said: “Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter and John Artis were also indicted for the Lafayette bar slayings.”

The twining of the Kavanaugh and the Lafayette bar murders fueled rumors for many years to come. Speculation centered on the role that the mob may have played in persuading the prosecutor’s office to pursue enemies of the underworld. The Mafia connection was more direct in the Kavanaugh case. Eight months after the killing, a small-time hood named Johnny “the Walk” DeFranco died from a slit throat, the victim of a gangland-style murder. Prosecutors put forth a theory that Judy Kavanaugh had been involved in a counterfeiting and pornography ring and was silenced when she panicked, while DeFranco was later killed to keep him silent about her death. Five people were ultimately indicted for one or both crimes, including Harold Matzner, the young publisher of a suburban newspaper company in New Jersey. He had backed a series of articles that tried to link the Passaic County Prosecutor’s Office to the underworld. All the defendants in both crimes, including Matzner, were ultimately acquitted amid allegations of witness tampering and gross misconduct inside the prosecutor’s office.

(#ulink_cf8471c0-f518-5e12-940c-f6bc9ed9b97a)

Carter’s indictment also generated discussion about the underworld in Paterson. Mobsters had approached Carter about throwing fights, but he had always refused. In theory, this would give the mob an incentive to turn against him—just as the mob had an incentive to turn against Harold Matzner. Rumors circulated that mobsters, seeking vengeance against Carter, gave the prosecutor’s office conclusive evidence of his guilt, but the evidence could never be introduced because of its origins. The rumor is fantastic, but it gained some currency over the years as prosecutors, seemingly armed with little direct proof of guilt against Carter or Matzner, pursed each man with zeal. Other unsettling parallels between the Kavanaugh and Lafayette bar murders would surface in time.

When Carter heard about his indictment on the radio, he was shocked. Even though he had hired a lawyer, he still believed that the authorities planned to release him. But after being jailed for about six weeks, he guessed that prosecutors sought the indictment against him because they feared a possible lawsuit against Passaic County for false arrest. (Carter had no such intention.) If a jury returned a verdict of not guilty, prosecutors could say they had done their best with the evidence they had. Carter’s shock soon gave way to fury and fear. He was now trapped in jail until his trial. With little to do, he began writing letters to people who had seen him on the night of June 16 and who could serve as his alibi witnesses.

To those who knew Carter, the accusation didn’t make sense. His friends and family believed he was capable of killing three people, but not in the fashion of the Lafayette bar murders. Despite his inflammatory comments in the Saturday Evening Post, Carter was known for advocating self-defense, specifically against police harassment. Violence was justified, indeed necessary, against aggressors, he argued, but not against innocent bystanders. Why would he walk into an inoffensive bar and shoot a room full of strangers? It never made sense, and the authorities offered no explanation.

Moreover, when Carter did exact revenge and lash out, he used only his fists. The rules of the streets were clear. Punks and sissies used guns or knives; warriors used their fists. If Carter wanted to punish or even kill someone, he would consider it an insult to his manhood if he did not use his bare hands. He would want the victim to know that it was “Hurricane” Carter meting out his punishment. Carter owned and occasionally carried guns, but that was because of his own fears—perhaps exaggerated, perhaps not—that he would be shot at. What is clear is that until the Lafayette bar murders, no one had ever accused Carter of pointing a gun at another person.

The Lafayette bar shooting “wasn’t Rubin’s style,” said Martin Barnes, an acquaintance of Carter’s who was elected mayor of Paterson in the 1990s. “If you were bad, you did it with your hands, and Rubin did it strictly with his hands.”

Carter initially wanted F. Lee Bailey to represent him, but the famed defense lawyer was already embroiled in the Kavanaugh case, so instead he hired Raymond Brown from Newark. Brown was known for being the only black lawyer in the state to take on whites. He did not, at first glance, look like a dragon slayer in his rumpled brown and gray suits, Ben Franklin-type bifocals, and a plaid hat. He smoked a pipe and ambled around in a kind of slouch, as if he were getting ready to sit down after every step. But he was an expansive orator whose voice filled a courtroom, a firebrand with a rapier wit. In his fifties, he had short, dust-colored hair and a high yellow complexion; in fact, he was light enough to pass for white. When he was in the Army, an officer candidate once told him, “Be careful, some people will think you’re a nigger.” “I am!” Brown shot back.

The trial against Carter and Artis took place at the Passaic County Court on Hamilton Street, where grandeur and tradition welcomed every visitor. Completed just after the turn of the century, the building featured large white Corinthian columns and a ribbed dome with a columned cupola; on it stood a blindfolded woman holding the scales of justice. In the courtroom where Carter was tried, the judge’s large dark wood desk stood on a platform in dignified splendor. On the desk lay a black Bible with its red-edged pages facing the gallery. An American flag stood to the side.

Paterson was a tinderbox as jury selection began on April 7, 1967. The establishment was terrified that blacks would riot if the defendants were found guilty. Black youths had rioted three summers before, and a conviction of Paterson’s most celebrated, most feared, most hated black man could trigger another firestorm. To quell any possible disturbance, the courthouse was transformed into a fortress, with extra uniformed and plainclothes police perched in the building’s halls and stairwells, on the streets outside, and on neighborhood rooftops. The roads around the building were blocked off. The authorities questioned known troublemakers and even rummaged through garbage cans in search of contraband. According to an internal FBI report dated May 27, 1967, an informant told the agency that in the “Negro district, five large garbage cans were filled with empty wine and beer bottles and some beer cans … and these might be a source of Molotov cocktails … and this condition could be caused by the feeling of people regarding the Carter-Artis trial.”

Presiding was Samuel Larner, an experienced New Jersey lawyer who had recently been appointed to the Superior Court in Essex County and had already developed a reputation as a no-nonsense judge. Larner gained widespread acclaim in the 1950s when he spearheaded an investigation of government corruption in Jersey City. The inquest triggered more than fifty indictments, culminating in the suicide of one employee and the resignation of several others. Sam Larner knew Ray Brown well. The two men were co-counsel for John William Butenko, an American engineer, and Igor Ivanov, a Soviet national, who just a few years earlier had been convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage.

Judge Larner had been reassigned from Essex to Passaic County, evidently because Passaic was either experiencing a shortage of judges or a backlog of cases. Carter always suspected he had been reassigned to keep Ray Brown under control. Larner intervened often when Brown was pressing witnesses, and their jousting was a running sideshow during the trial.

Each day during the voir dire, for example, the proceedings lasted into the early evening. Then one afternoon Judge Larner abruptly rose at 4 P.M. and declared, “The court is adjourned.” The stunned courtroom silently watched the judge walk toward his chamber. Suddenly, Ray Brown stood up.

“Judge Larner!”

“What is it now, Mr. Brown?”

“Tell me, Judge Larner, why is this night different from all other nights?”

It was the first night of the Jewish holiday of Passover, and the judge needed to get home. He first glared at Brown for his effrontery in questioning a judge’s decision to end the day prematurely. Then he realized Brown’s clever invocation of a line from the Passover Seder. Larner smiled at his former colleague and continued out the door.

Carter, however, found little to smile about. He had never been on trial before. When he did something wrong, he owned up to it, as he had ten years earlier when he pled guilty to robbery and assault. Carter figured he was in trouble during jury selection, a three-week ordeal that saw one potential juror dismissed for being a member of Hitler’s youth movement in Germany and another for believing that blacks who grew up in ghettos were more prone to violence. Despite such efforts, the jury that was selected comprised four white women, nine white men, and one black man—a West Indian. Fourteen jurors in all, two of whom would be selected as alternates at the end of the trial. This was a jury of my peers? Carter thought. Aside from being a different color than all but one of them, I probably had more education than any person sitting on the jury, and even I didn’t understand a damn thing that was going on.

The prosecuting attorney was Vincent Hull, the son of a state legislator, whose precise, low-key manner contrasted sharply with Brown’s showmanship. Hull was young, slim, and conservatively dressed with prematurely gray hair. In his opening statement, he described how the two defendants, after circling the bar in Carter’s 1966 Dodge, parked the car, walked into the Lafayette bar, and without uttering a word “premeditatedly, deliberately, and willfully” shot four people, killing three of them. Hull meticulously described the victims and their wounds and asserted that Detective Emil DeRobbio found an unspent 12-gauge shotgun shell and an unspent .32 S&W long bullet in Carter’s car. Those were the same kinds of bullets, Hull said, used in the bar shooting. When Hull completed his opening, he thanked the jury and sat down.