По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

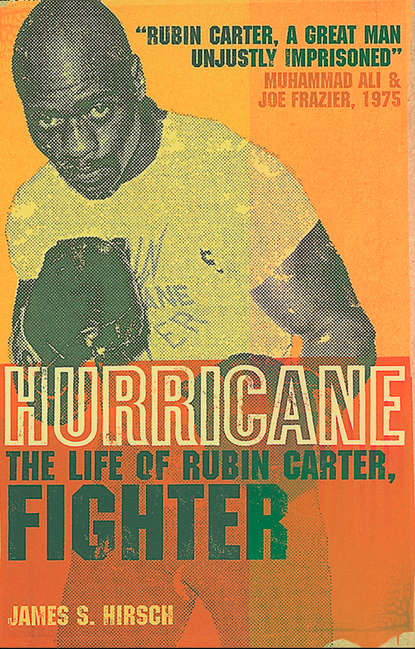

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Judge Larner turned to the defense table. “Mr. Brown,” he said.

Ray Brown rose from the table, his glasses perched on his nose and a legal document in his hand. While the prosecutor had not mentioned race except as it related to the identification of the suspects, Brown argued that Carter stood accused because the police were looking for a Negro on the night in question, and therefore every Negro was suspect. Brown told the jury that Carter didn’t know what happened in the bar and refuted Hull’s assertions point by point, including the alleged discovery of bullets in the Dodge. If the police actually found the bullets on the night of the crime, Brown asked, why wasn’t Carter arrested then instead of four months later?

To convict, the state needed a unanimous vote of guilt from the jurors, so Brown’s strategy was to direct his entire defense to the West Indian juror, hoping to persuade him that the state was victimizing his client. “Any man can be accused,” Brown thundered, “but no man should have his nerves shredded and his guts torn out without a direct charge.”

“Mr. Brown!” Judge Larner exploded. “I don’t want to interrupt you, but I think it is time you limited yourself to the facts to be shown, and let’s get beyond the speeches on philosophy.”

“This is not philosophy, Your Honor. This is a fact.”

The state’s first witness, William Marins, who lost his left eye in the shooting, set the tone for the trial. Carter had hoped that Marins, a balding, stocky man in his forties who was the lone survivor of the tragedy, would convince the jurors that he and Artis were not the gunmen in the same way he had convinced the police at St. Joseph’s Hospital after the shooting. Marins was now an unemployed machinist—and an unsympathetic witness. He told the court that on the night of the crime, he had been shooting pool and drinking beer with another patron, Fred Nauyoks. Also in the bar were Jim Oliver, the bartender, and Hazel Tanis. Suddenly, two colored men entered the place between two-thirty and three o’clock in the morning, shooting everyone inside. One gunman, with a mustache, swung a shotgun. The other, standing directly behind him, had a pistol. Marins said he felt a sharp pain in the left side of his head, noticed smoke curling out of the shotgun barrel, and passed out. When he awoke, “I was bleeding and bleeding and bleeding. I waited for the police to come.”

Throughout the questioning, Marins emphasized that he was in a state of shock after the shooting and was in no condition to identify the gunmen. By the time Brown began his cross-examination, it was clear Marins was not about to exonerate Rubin Carter and John Artis.

“Do you feel like testifying some more, Mr. Marins,” Brown asked, “or would you like a glass of water?”

“No,” Marins snapped.

“You gave a statement to the police about what happened in this place, did you not?”

“Yes, but I was in a state of—”

“I didn’t ask you, sir—” Brown said.

Judge Larner interrupted. “Just answer the particular question, Mr. Marins.”

Brown produced numerous official statements that Marins had given about the shooting, one as late as October 20, 1966. “Now, you repeatedly told these officers, did you not, that [the gunmen] were thin, tall, light-skinned Negroes, didn’t you?”

“I said they were colored,” Marins protested.

Carter, of course, was short, thickly built and black as soot, so Brown homed in on Marins’s previous descriptions, which seemed to have ruled Carter out as a suspect. Shuffling between the witness stand and the defense table, Brown noted that his description matched that of Hazel Tanis, who told police before she died that the gunmen were about six feet tall, slimly built, light-complexioned and had pencil-thin mustaches. Isn’t that the same description you gave? Brown asked Marins.

“No!” Marins insisted. “I told [the police] the man had a dark mustache, or well, it was a mustache. I didn’t look at him that long … I was in a state of shock.”

Brown had one more card to play. “Your Honor, please. At this time I would like to ask that Your Honor unseal depositions given by this man in a civil suit brought by him in January of 1967.”

Carter had no idea what was going on.

“Mr. Marins,” Brown said, “do you know that you are the plaintiff in an action against Elizabeth Paraglia owner of the Lafayette Grill?”

“True.”

“Do you recall having testified in depositions taken before a notary public … on December 16, 1966?”

“True.”

“Do you recall signing these depositions and stating under oath they were true?”

“True.”

“You were out of the hospital?”

“True.”

“You had been discharged?”

“True.”

“Your health then permitted you to go to a lawyer’s office and give depositions, is that correct?”

“True.”

“Your lawyer was present?”

“True.”

Brown bored in. “You were asked, ‘Did you recognize the men who shot you?’ Your answer: ‘I know they were colored, light-colored, and one in particular, the first one with a shotgun, had a mustache that I just happened to see, and the man in back of him was about the same height.’ Did you give him that answer?”

“True,” Marins replied meekly.

“You were asked, ‘How tall are they?’ You said, ‘Six feet, maybe five eleven, six feet.’ Is that correct?”

“Well, I said six feet. Maybe.”

“Isn’t it a fact that you told Detective Callahan six feet, slim build, sir?”

“When was this?”

“June 17, 1966, in the emergency room.”

“I don’t remember because I was in a state of shock.”

“Were you in a state of shock in December 1966?”

The judge had seen enough. “He said no, and he doesn’t remember what he told Detective Callahan, whether it is the same or not.”

Brown had cut Marins to shreds, but there was no joy at the defense table. The lone survivor had inexplicably changed the very statements that had once helped clear Carter and Artis of suspicion, and Carter quietly seethed.

Despite his renowned temper, Carter remained calm during the proceedings. Hundreds of times he had to stand up before prospective jurors to be identified, but he never balked or showed any annoyance. The Evening News said he acquired the stance of a “mild-mannered student.” His wife brought him a clean suit and dress shirt every night at the jail, and throughout the trial he took copious notes on a yellow legal pad. Only once did Carter vent his rage in the courtroom. His nemesis, Vincent DeSimone, sat next to Hull at the prosecutor’s table. During one recess, Carter’s daughter wandered over to the table and began playing and laughing with the lieutenant. Carter bolted out of his seat and grabbed the three-year-old.

“Come here,” he said. “You don’t talk to this punk. He’s trying to put your father in jail.”

DeSimone leaned back and smiled.

“Fuck you, you fat pig,” Carter said. “You leave my daughter alone.”

The state had little evidence linking Carter and Artis to the shooting. The police had neglected to brush the Lafayette bar for fingerprints or conduct paraffin tests on the defendants’ hands after they were picked up. There were no footprints, no bloodstains, no murder weapons, no motive. There was conflicting testimony about Carter’s car. One witness, Patricia Graham Valentine (Patricia Graham at the time of the shooting), lived in an apartment above the bar. She said Carter’s white Dodge “looked like” the getaway car; both cars had triangular, butter-fly-type taillights. But another witness, Ronnie Ruggiero, also saw the getaway car and testified that he thought it was a white Chevy, not a white Dodge. Ruggiero, a white boxer, had driven in Carter’s Dodge Polara before. Then there were the bullets. Detective DeRobbio testified that he found a .32-caliber S&W lead bullet and a Super X Wesson 12-gauge shotgun shell in Carter’s car. But ballistics experts testified that the bullets found at the crime scene were .32 S&W long copper-coated bullets and Remington Express plastic shells. The bullets in Carter’s car were indisputably different from those used in the crime, but Judge Larner allowed the lead bullet into evidence because it could have been fired from a .32-caliber pistol. The same could have been said for the 12-gauge shell, but Larner still excluded that as evidence. His logic confounded the defense team.

The state’s case rested on the shoulders of its two eyewitnesses, Alfred Bello and Arthur Dexter Bradley. As a thief, Bello was more pathetic than petty. By the age of twenty-three, he had already been convicted five times on various charges of burglary and robbery. In one instance, he robbed a woman of a makeup case valued at one dollar, a cigarette case valued at two dollars, and a pocketbook valued at twenty dollars. Carter assumed that the reward for his conviction, now up to $12,500, looked mighty tempting compared to such nickel-and-dime thieving. A heavy drinker who had threatened his classmates with a penknife in grade school, Bello had spent so much time in Paterson’s police headquarters that DeSimone’s secretary referred to him as the lieutenant’s adopted son. Bello was short and fat with greased-back hair. He talked too loud and he wore high-heeled shoes. He had a tattoo on his right arm that read: “Born to Raise Hell.” He had been discharged from the Army for fraudulent enlistment. He had also been in state reformatories off and on for several years, and he was out on parole when the Lafayette bar shooting occurred. At the time of the murders, he was serving as “chickie,” or lookout, for Bradley’s break-in at the Ace Sheet Metal Company.