По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

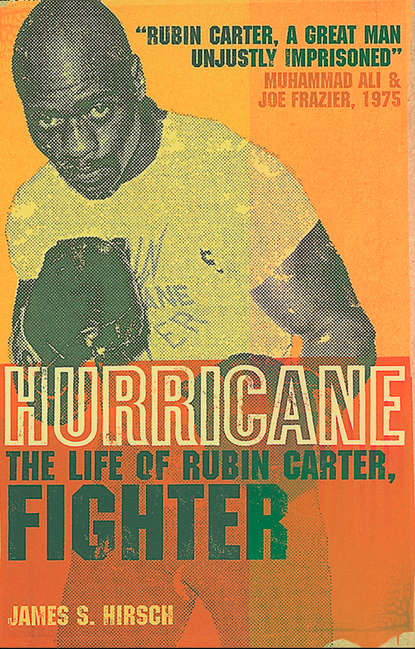

Hurricane: The Life of Rubin Carter, Fighter

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Mullick rolled his eyes. “What size shoe do you wear?” he asked.

“Eight and a half,” Carter responded.

“You need boxing shoes,” Mullick said, more in pity than disgust. He fetched a pair from one of his own boxers and Carter sheepishly made the switch. Now he was ready.

The bell rang.

Glenn came out dancing, jabbing, grunting, contemptuous of this no-brain, no-brand opponent who presumed to step into the ring with the champion. Carter tried to stay beneath his crisp left hand, pursuing his adversary like a cat in an alley fight. Carter bobbed, feinted, ducked, then lashed out with his first punch of the fight—a whizzing left hook that caught Glenn flush on his chin, spilling him to the canvas. The blow may have startled Carter as much as Glenn.

Glenn bounced up quickly but was now groggy. He was surprised by the power of a mere welterweight. Carter returned to the attack and bored in with a quick, crunching left hook, then another, then a third, the last shot sending Glenn’s mouthpiece flying out of the ring. Nelson’s eyes turned glassy, his arms fell limp, and he started sinking softly to the canvas. Carter realized he could hear himself panting; the crowd was stunned into silence. Then pandemonium erupted. Spectators stood on their seats, whooping, gaping in disbelief at the knocked-out champion, cheering long and hard for Carter. The former hoodlum was now a hero. He had cocked a Sunday.

The triumph did more for Carter than prove he could slay a Goliath. It gave his life purpose and legitimacy. The boxing ring became his new universe, a place where his splenetic spirit and brawling soul were not only accepted but celebrated. His enemy couldn’t hide behind a warden’s desk or a police badge. He now stood face-to-face with his rival, and each bout had a moral clarity: the best man won, and if you fight Rubin Carter, you better bring ass to get ass.

After the Nelson Glenn fight, Carter never held an Army weapon again. Mullick cut through the Army’s red tape and transferred Carter to a Special Service detachment for boxers for the 502nd. They lived in their own building, three glorious floors for twenty-five men. The first floor held a vast recreational area, with ping-pong tables and pool tables, as well as a kitchen. The second floor was sectioned off with bathtubs and shower stalls, whirlpools and rubbing tables, while the top floor had secluded sleeping quarters. This was nirvana in the Army.

Carter was accepted immediately by the other boxers, including Glenn. For one who always preferred isolation, he felt strangely comfortable with these men. Some were black, some were Hispanic, some were white, but they were all fellow warriors. They felt no need to engage in the braggadocio common among the other soldiers. The only vocabulary that mattered was boxing. Past fights, future fights, championship fights. Carter spoke the same language as everyone else, and winners had the final say.

Soldiers who saw Carter’s matches have vivid memories of them more than forty years later. William Mielko, an Army sergeant, remembered Carter’s entering the ring in Munich to fight a member of the 503rd regiment. When the announcer declared the names of the boxers, two bugles blared, and a six-foot six-inch, 250-pound heavyweight entered the ring wearing a black hood over his head with two slits for his eyes. His body was wrapped in shackles. It was a frightening spectacle, but when the heavyweight rid himself of the hood and chains, he faced Carter. “Carter looked over at his trainer,” Mielko recalled, “and the trainer said, ‘First round.’ ” And that was the round in which Carter knocked him out with a furious combination of punches.

In one year Carter won fifty-one bouts—thirty-five by knockouts—and lost only five, and he won the European Light Welterweight Championship. But he was even more proud of a very different accomplishment.

Again, it was Hasson who tackled the matter of Carter’s speech impediment. No one had ever spoken to Carter about his stuttering except his parents, who said that the problem would disappear if he stopped lying. Rubin was at a loss. All he knew was that if anyone laughed at his clumsy tongue, he would flatten him. Hasson, however, saw Carter’s speech problem as a barrier not only to communication but to knowledge. Wrapped in a coat of silence, Carter came to believe what others said about him: he didn’t talk because he was dumb, and education was useless for someone with such low intelligence.

When they first met in the drop zone, Hasson’s comment—“I think you’ve got a problem”—was an oblique reference to Carter’s stammer. Later, on one of their walks across the base, Hasson spoke bluntly: “Your stuttering is a permanent troublemaker, and if you’re too embarrassed to go back to school, then I’ll go with you.”

The two men enrolled in a Dale Carnegie speech course at the Institute of Mannheim, where they were briefly stationed. The institute breathed prestige, with tall white marble columns and long, winding staircases. Carter thought it looked like something the Third Reich would have built. Many of the German students spoke more English than Carter did. The classes themselves were taught by kind, middle-age German men who imparted sage advice.

“Just think about what you’re going to say first, then say it,” one teacher said. Carter learned that he could sing songs without stammering, and he was able to replicate the relaxed fluidity of music in his own speech. He practiced by chanting Army cadences (“Hup-Ho-o-Ladeeoooo!”) as well as gospels from his church in Paterson. Words soon flew out of his mouth like doves released from a cage. Freedom! Powerful oratory was no stranger to Carter. He had five uncles and a grandfather who were all Baptist preachers, and his father’s voice was so resonant that churchgoers sat near him just to hear him pray. Rubin too proved to be a persuasive, even gifted, speaker who used ministerial cadences in stem-winding speeches. He also felt free to expand his own mind. His formal education had ended in eighth grade, and the only books he ever read were cowboy novels. Now he attended classes on Islam four nights a week and embraced Allah, renaming himself Saladin Abdullah Muhammad. “Allah is in us all, and man himself is God,” Hasson told Carter.

While Carter’s new religious faith would wane over the years, his discovery of books and passion for knowledge sustained him through his darkest hours. He never forgot what Hasson once told him: “Knowledge, especially knowledge of oneself, has in it the potential power to overcome all barriers. Wisdom is the godfather of it all.”

Discharged from the Army on May 29, 1956, Carter returned to Paterson with the intention of becoming a professional prizefighter. But he quickly discovered that he could not elude his past. He was arrested on July 23 for escaping from Jamesburg and sent to Annandale Reformatory, where inmates’ short-short pants evoked the image of incarcerated Little Bo Peeps. Carter was released from Annandale on May 29, 1957, but embittered about his reincarceration, he shelved his boxing ambitions, got a job at a plastics factory, and began drinking heavily. He liked to spend time at Hogan’s, a club that attracted pimps and hustlers, pool sharks, and virtually every would-be gangster in the black community. Carter was enthralled by the diamonds they wore, the bills they flashed, and the luster of their shoes.

Less than five weeks after he was released from Annandale, Carter left Hogan’s one day after a good deal of drinking. Walking through Paterson, he went on a brief, reckless crime spree. He ripped a purse from a woman, a block later struck a man with his fist, then robbed another man of his wallet. All the victims were black. When Carter reported to work the next day, the police arrested him. He pled guilty to the charges of robbery and assault but could never explain or excuse why he committed the crimes. He served time in both Rahway and Trenton state prisons, where he received various disciplinary citations for refusing to obey orders and fighting with other inmates. He did not make a particularly good impression on prison psychologists. In a report dated August 30, 1960, one psychologist, Henri Yaker, commented on Carter:

He continues to be an assaultive, aggressive, hostile, negativistic, hedonistic, sadistic, unproductive and useless member of society who will live from society by mugging and who thinks he is superior. He has grandiose paranoid delusions about himself. This individual is as dangerous to society now as the day he was incarcerated and he will not be in the streets long before he will be back in this or some other institution.

Carter was released from prison in September 1961, but that description—assaultive, sadistic, useless—would be used against him long into the future.

In the sixties, the center of the boxing universe was the old Madison Square Garden, with dingy, gray locker rooms and a balcony where rowdy fans threw whiskey bottles at the well – dressed patrons below. During bouts, a haze of smoke from unfiltered cigarettes hovered in the air. Men in sport shirts sipped from tin flasks in between rounds, while other fans sat with cigars, lit or unlit, that never left their lips. The Friday-night fights, televised across the country and sponsored by the Gillette Company, were an institution, and a marquee boxer could earn tens of thousands of dollars. But before reaching the big time, the pugs had to fight in satellite arenas in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, Akron, and elsewhere. In later years, cable television would put any hot boxing prospect on the air after only a few fights. But at this time fighters typically had to learn their craft and pay their dues over several years before receiving that sort of publicity.

Rubin Carter felt he had paid his dues—in prison. While incarcerated, he concluded that prizefighting was his best hope of making a living and avoiding trouble. He trained in prison yards for four years, lifting weights, pounding the heavy bag, and accepting bouts with all comers. Once he left prison and entered the ring as a professional, it was soon evident that few could match his blend of intimidation, theatrics, and might. This crowd-pleasing style resulted in his first televised fight only thirteen months after he turned pro, when he knocked out Florentino Fernandez in the first round with a right cross to the chin. A black-and-white photograph of Fernandez falling out of the ring, his body bending like a willow over the middle rope as Carter glared down at him, sent an unmistakable message: the “Hurricane” had arrived.

Carter never really liked his boxing nickname. It was given to him by a New Jersey fight promoter, Jimmy Colotto, who saw the marketing potential of depicting a former con as an unbridled force of nature. Carter’s preferred symbol was a panther. In the ring, Carter’s trainers wore the image of a panther’s black head, its mouth open wide, on the back of their white cotton jackets. The image had nothing to do with race or politics (the Black Panther organization was not formed until 1966). Carter simply admired the panther’s speed and stealth, its predatory logic.

But Hurricane stuck, and for good reason. When Carter entered the ring, he was a force of nature. His head and face were already glistening from a layer of Vaseline. He wore a long black velvet robe and a black hood knotted with a belt of gold braid. There was something ominous, even alien, about him. When the Pennsylvania State Athletic Commission ordered Carter to shave his goatee for a fight in Philadelphia, some sportswriters opined that the goatee was the seat of Carter’s power. The boxer looked foreshortened and brutally compact. The lustrous pate, the piercing eyes, the bristling beard, the sneering lips—and the violent criminal record—sent frissons of fear and delight through the crowd. Before a match, the announcer would introduce other boxing champions, past and present, in the crowd, and the conquerors would hop up in the ring, wave to the fans, and shake hands with the opposing fighters. Carter, however, refused to shake hands or even acknowledge their presence. Prowling around the canvas, he kept his eyes down and, in the words of one opponent, looked like “death walking.” When the battle began, he attacked straight on, punches whistling. No dancing, no weaving, no finesse. He rarely jabbed. Just heavy leather. Carter liked the violence.

While Carter often found trouble on the streets, his training camp in Chatham provided sanctuary. He and several sparring partners escaped to camp six weeks before a bout. They awoke at 5 A.M. and ran up to twenty miles through steep, wooded hills. Carter liked the dark frigid mornings best, when icicles formed in his goatee and the only sounds were the pounding of shoes on pavement and the stirrings of a sleepy cow.

After an eggs and bacon breakfast and rest time, Carter resumed his training in the small gym. He jumped rope for forty minutes, pumped out five hundred pushups, lifted neck weights, pounded the heavy bag and speed bag, pushed against a concrete wall to build muscle mass, and did chinups until he dropped.

A sparring session was no different from a televised fight: in each, Carter locked out the rest of the world and tried to destroy his opponent. At the beginning of his career, he lived in Trenton and trained in the same Philadelphia gym as Sonny Liston, the feared heavyweight who reigned as champion from 1962 to 1964. Liston’s heavy blows made it difficult for him to find sparring partners. One day Carter volunteered to go a few rounds, despite giving up five inches and fifty pounds. While most boxers spar to improve their footwork, punching combinations, or defensive maneuvers, neither Liston nor Carter had the patience for such artistic subtleties. Both were former convicts—Liston for armed robbery—and they rarely exchanged more than a few words. Theirs was an unspoken code of respect through pugilistic mayhem, and they sparred fiercely and repeatedly. But after one three-round session, Carter removed his battered headgear and found it soaked with blood. He was bleeding from both ears. He fled from Trenton that night and moved to Newark. He knew if he returned to the Philadelphia gym the next day and Liston needed a partner, he would do it again. He could never turn down a challenge, even if it meant risking serious injury.

Like Liston, Carter beat his sparring partners unmercifully. To soften the blows, Carter used oversize gloves and his partners wore a foam rubber protective strap around their ribs. In training camp, he sparred against three or four boxers a day, always punching against a fresh body. These sessions were followed by more calisthenics, then by a few rounds of shadowboxing, then by a shower and a rubdown. After a dinner of steak, fish, or chicken, Carter took a walk in the clean country air and thought about the next day’s workout.

Only two years after he became a professional fighter, Carter wanted a shot at the middleweight title. He had won eighteen and lost three, with thirteen knockouts. But in October 1963, he lost a close ten-round decision to Joey Archer, and he needed a victory to put him back on track for a shot at the championship. That put him on a collision course with Emile Griffith.

Griffith was a native of the Virgin Islands who moved to New York when he was nineteen. His boss encouraged him to try his hand at boxing, and he was an instant success, winning the New York Golden Gloves. He turned professional at twenty. Griffith liked to crouch in the ring, stick his head in the other guy’s chest, and pound the midsection. He could also dance and jab, backpedal and attack; he never tired. And he was deadly. In a bout at Madison Square Garden on March 24, 1962, Griffith took on Benny “Kid” Paret for the third time in less than twelve months, the decisive match in a bitter war between the two men. Paret provoked Griffith at their weigh-in by calling him maricon, “faggot.” That night, Griffith was knocked down early, but he pinned Paret in the corner in the twelfth round and felled him with a torrent of angry punches, prompting Norman Mailer to write later: “He went down more slowly than any fighter had ever gone down, he went down like a large ship which turns on end and slides second by second into its grave. As he went down, the sound of Griffith’s punches echoed in the mind like a heavy ax in the distance chopping into a wet log.”

Paret was removed from the ring on a stretcher, lapsed into a coma, and died ten days later; he was twenty-five.

At the end of 1963, Griffith was the champion of the welterweight division (for boxers 147 pounds and under) and had been named Ring magazine’s Fighter of the Year with a record of thirty-eight wins and four losses. Now he wanted a shot at the middleweight crown (for boxers 160 pounds and under), and that led to his match with Carter.

Their bout was to take place in Pittsburgh’s Civic Arena on December 20. The two men were sparring partners and friends, but in the days leading up to the match, Carter launched a clever campaign to strike Griffith at his point of vulnerability: his pride. The idea was to provoke him before the fight so that he would abandon his strongest assets—his speed and stamina—and go for a quick knockout. Carter began planting newspaper stories that Griffith was going to run and hide in the ring and hope that Carter tired. In a joint television interview the day before the fight, the host asked Griffith if he dared to stand toe-to-toe with the Hurricane.

“I’m the welterweight champion of the world,” Griffith snapped. “I’ve never run from anyone before, and I’m not about to start with Mr. Hurricane Carter now!”

“Then I’m going to beat your brains in,” Carter shot back.

Griffith laughed in the face of Carter’s hard glare. “I’ve never been knocked out either,” Griffith said. “But if you don’t stop running off at the mouth, Mister Bad Rubin Hurricane Carter, I’m going to turn you into a gentle breeze and then knock you out besides.” Griffith was now seething, so Carter raised the temperature a little more.

“Knock me out!” Carter said, turning to the live audience. “If you even show up at the arena tomorrow night, that’ll be enough to knock me out! I oughta cloud up and rain all over you right here. You talk like a champ, but you fight like a woman who deep down wants to be raped!”

The audience, knowing what happened to Benny Paret, gasped. Griffith clenched his jaw. Carter had laid his trap.

The following night, the city’s steel plants and foundries spewed smoke into the frozen air. Inside the Civic Arena, Griffith’s mother was in the crowd, and the champion entered the ring as a confident 11–5 favorite. Griffith started out methodically, firing jabs, standing toe-to-toe, swapping punch for punch. He wanted to prove that he could take Carter’s best shots and win a slugfest. This was exactly what Carter had hoped for.

Carter popped him in the mouth with a stiff jab; Griffith responded with an equal jolt to Carter’s mouth. Carter pumped a jab to his forehead; Griffith fired one back on him. Carter backed up, looked at him, snorted, then raced in with a jab followed by a powerful left hook to the gut.

The air came out of Griffith, who tried to grab Carter, but Carter slipped away. “Naw-naw, sucker,” Carter mumbled through his mouthpiece. He drilled home another salvo of lefts and rights—“You gotta pay the Hurricane!” Carter yelled—then dropped Griffith with a left hook.

“One! … Two! … Three.”

The crowd was stunned into silence, then stood and cheered. Griffith staggered to his feet to beat the count, but he was now an easy target. Carter smashed left hooks to the body and devastating rights to the head. Griffith dropped to the canvas, badly hurt. He tried to stand but stumbled instead. The referee, Buck McTiernan, stepped in and stopped the fight. The time was two minutes and thirteen seconds into the first round. “A left hook sent Griffith on his way to dreamland!” the television announcer yelled.

Carter’s upset cemented his reputation as one of the most feared men in boxing. It also earned Carter a shot at the title the following year. But the Griffith fight marked the pinnacle of his boxing career. Carter lost his championship bout on December 16, 1964, to Joey Giardello, a rugged veteran whose first professional fight had been in 1948, in a controversial fifteen-round decision. Giardello’s face was puffed into a mask while Carter was unmarked, and a number of sportswriters who saw the fight thought Carter won. But challengers typically have to beat a champ decisively to win a decision, and Carter didn’t.

The bout occurred on December 16, 1964. The following year, Carter received another jolt—this time, political. He was invited to fight in Johannesburg, South Africa, a country about which he knew virtually nothing. He had never heard of Nelson Mandela or the African National Congress or even apartheid. But just as the Army exposed him to bigotry in the Deep South, boxing now put him in the midst of a more virulent racism. Arriving in Johannesburg a couple of weeks before his September 18 bout, he was guided around the city by Stephen Biko. In years to come, Biko would become the leader of the Black Consciousness movement, advocating black pride and empowerment, and would found the South African Students Organization. But in 1965, he was an eighteen-year-old student and fledgling political activist, and he gave Carter a quick education in black oppression. Walking through Johannesburg, the American’s roving eye glimpsed a tight-skirted white woman. “Whoa, man!” he said. Biko grabbed Carter’s arm. “You can’t say that. They’ll kill us! They’ll kill us!”

Racial strife was indeed high. The previous year, Nelson Mandela and other black leaders were handed life sentences for conspiring to overthrow the government. The ANC had been banned in 1961; but clandestine meetings were still being held, and Biko took Carter to some of these nocturnal gatherings. There he learned about black South Africans’ bloody struggle, dating almost two hundred years, for political independence. He also had his own encounter with the South African police. He was almost arrested one night for walking outside without a street pass.

The boxing match was against a cocky black fighter named Joe “Ax Killer” Ngidi who had a potent right hand. More than 30,000 fans packed into Wemberley Stadium on a sunny afternoon, and as Ngidi danced about the ring in a pre-bout warm up, Carter noticed that some of the fans were carrying spears.

“I don’t know what that means,” his advisor Elwood Tuck told him, “but get that sucker out of there quick.”

Carter was confident. South African boxers, he believed, viewed the sport as dignified and noble but lacked savagery. That shortcoming could not be applied to Carter, and even though he was a foreigner, his ferocity made him a crowd favorite in South Africa. When he KO’d “Ax Killer” Ngidi in the second round, fans stood on their feet, raised their spears and yelled, “KAH-ter! KAH-ter!” But after Carter reached his dressing room, he was pinned in by a mob of supporters, and the scene turned ugly. To leave the stadium, a battalion of gun-carrying Afrikaner cops formed a wedge and told Carter and his entourage to follow its lead. As they pushed through the crowd, a white officer pummeled several black fans. Carter, outraged, moved to strike the cop, but was blocked by one of his handlers and was once again reminded that such a move would ensure his own demise.

In the following days, Carter was named a Zulu chief outside Soweto and given the name “Nigi”—the man with the beautiful beard. He was now an African warrior, and he wanted to apply the same principles in his second homeland that he always applied in the U.S.: blacks must use whatever means necessary, including violence, to defend themselves. From what he could tell, South African blacks were defenseless, armed with rocks and spears against the Afrikaners’ guns and rifles. Before Carter left Johannesburg, he pledged to Stephen Biko that he would return.