По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

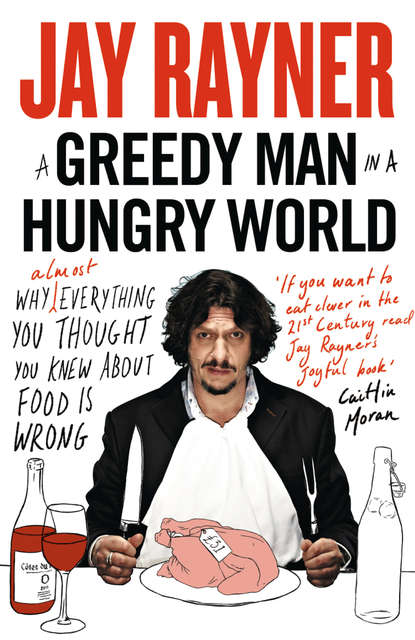

A Greedy Man in a Hungry World: How

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I nodded sagely. As I had suspected, this was a game I was going to win. I gave them the big reveal, told them about Lidgate’s and the £31 chicken. There was an electronic gasp of horror. Thirty-one pounds? Too much. Absurd. Ludicrous. Bizarre.

Just wrong.

‘I once saw a woman run out of Lidgate’s in tears over the price of a chicken,’ one person said. I answered that I could well imagine such a thing.

My warped, obsessive, competitive streak now took me on a tour of London’s classiest butchers, desperate to prove that I had spent the most it was possible to spend on a chicken. For some reason it mattered that the bird which now sat in my freezer awaiting its moment, the bird which had become such a talking point on Twitter, should be able to hold onto its title. I saw birds that were local and free-range and hand-reared and hand-plucked and hung with their guts in. I went to Harrods, where the food hall throngs with tourists who have no intention of buying anything other than tins of branded tea, and looked at shrink-wrapped birds from unpronounceable places in France. I did kilo-to-pound-weight calculations in my head, asked bored butchers to weigh chickens for me and pronounce on the price, and moved on, each time satisfied I was still ahead.

And then I went to the meat counter at Selfridges’ food hall, which is run by a highly respected butcher called Jack O’Shea. There I met the £51 chicken. It was a Poulet de Bresse, a particular breed which was granted Appellation d’origine contrôlée, or AOC, status in 1957, protecting it as a name for a particular type of bird, prized for its gamey flavour and rich fat. A nice chap behind the counter called Les, who wasn’t wearing a straw boater, told me they were special ‘because of their diet. They’re treated like royalty, they are.’ The bird I was looking at, with its head, neck, and feet on, and guts in – when you bought a bird from Bresse you got to pay for a lot of things you might not actually want – cost over £22 a kilo, and it was well in excess of two kilos.

Damn.

Damn, damn, damn.

There was I thinking I had bought the Bentley of chickens, with metallic paint and sports settings on the gearbox, when it was nothing of the sort. It was just a mid-range BMW. It was an Audi with under-seat heating, the kind of thing a desperate sanitary-ware salesman trying to prove his worth might buy as a way of declaring he had arrived, when in truth all it did was signal loud and clear to anybody who could bother to be interested that he had barely got started.

I wondered, even then, whether I had finally reached the zenith of the luxury chicken business and quickly discovered I had not. One evening, in the kitchens of London’s Savoy Hotel, I came across Heston Blumenthal, the chef of the famed Fat Duck in Bray, which has three Michelin stars. He was there overseeing the preparation of the starter for a big charity dinner I was attending. I had snuck away from the velvet plush and precious gilding of the ballroom to the bright lights and hard surfaces of the kitchen, where I always felt more comfortable, and stood there in my dinner jacket, picking his brains about chickens. A few years before he had made a TV series called In Search of Perfection which involved finding and then roasting the perfect chicken. I wondered how much he had spent on the birds. He thought about £45 each. He talked about the quality of Label Anglais chickens, a British-reared bird which was supposed to challenge the big names of the chicken world.

‘But there are even more expensive ones.’ Like what? He mentioned the birds from Bresse. Well yes, I knew all about those. ‘It’s the cockerels, though. They only sell them for about two weeks of the year around Christmas,’ he said, hand-sown into muslin bags. ‘They have this fabulous skin. ‘It’s like silk.’

And how much would one of these Bresse cockerels set me back?

‘About £120.’

There was, it seems, always a more expensive chicken out there somewhere.

I went to university in the eighties with a bloke called Eugene, who was thinner than me, smarter than me, and got much more sex than me. His name isn’t really Eugene; it is, naturally enough, something far cooler than that, but it pleases me to take my revenge by giving him a really crass pseudonym, because he was horribly annoying. Though obviously not to the parade of pretty girls who were willing to go to bed with him.

Eugene had read an awful lot of Jacques Derrida and Roland Barthes and, pace the kings of postmodern philosophy, liked to refer to things as ‘signifiers’ and ‘symbols’. Nothing was merely itself. In his universe everything was representative of its place within a long-drawn-out discourse; the physical world in which we lived was merely a set of these signifiers and symbols that had to be reconfigured and understood through their conversion to language. Or something. A pint of beer was never just a pint of beer. It was a signifier for the pursuit of a certain type of human experience, a way of managing communication, usually with one of the women who, a few drinks to the bad, had failed to recognize Eugene as the sociopath he was. (I’m really not bitter.) A bike was actually a signifier for modes of property ownership and an understanding of forward motion. A five-pound note was … something he cadged off you just before last orders in the back end of term when his money was running out, so he could buy this girl he’d just met another drink. Can you see just how bloody irritating Eugene was?

Which was why it was all the more infuriating that thinking about the £31 chicken had in turn made me think about Eugene and his tiresome language of symbols and signifiers. For it was clear to me that this ridiculously expensive bird was so much more than just three kilos of prime protein, delicious fat and potentially luscious crisp skin. It could stand – Lord help me – as a symbol for so many of the arguments and battles that we are, and need to be, fighting over food in the early years of the twenty-first century.

Certainly it couldn’t be dismissed as an object that was merely about wealth. I have long said that there is nothing wrong with paying large amounts of money for food experiences. Some people like to shell out for opera tickets or seats at cup finals to watch their team compete. They are buying memories, and an expensive restaurant experience is no different.

But an expensive restaurant experience is only that. You can’t go to, say, the Fat Duck for something as banal as chicken nuggets. You can’t even go there for deconstructed, ironic chicken nuggets (yet). You can only go there for a luxury experience. And sure, my £31 chicken could be given the full de luxe treatment: it could be pelted with truffles, stuffed with lobes of foie gras and basted with the richest of butters. (I can recommend a great place for something like that if you fancy it.) On the other hand it really could just be turned into chicken nuggets. However expensive the raw ingredient, it can still be converted into something very ordinary, which is precisely why the debate on Twitter had kicked off. Hell, it’s just a bloody chicken, and you make broth out of those for loved ones when they’re snotty and feverish. You barbecue their wings and drumsticks for kids’ parties, and put the breasts into pies with leeks and the kind of mustard-heavy cheese sauce that completely obscures the nature of the bird that provided the meat in the first place.

It was clear to me that wrapped up in this single bird were arguments over how we rear our livestock and the amount we are willing to pay for it: about provenance, sophisticated food marketing, the supply chain, and the value of small, local shops over large supermarkets; about the imperative to eat meat and the competing imperative to cut down on it; about the roles of money, status and class in what we eat; and the difference between what we want and what we need. In short, this one big-titted hen had become what Eugene would have called a huge signifier for the warped morality of our food chain.

That’s the point. I am in no doubt that the way we in the developed world think and talk about food has become warped; that most of the time we are completely missing the point. On television, online and in the glossy press we are bombarded with pornified images of food which attempt to cast the most expensive of ingredients as less a luxury than an ideal to which we should all aspire. In this world view any form of mass production or mass retailing is an evil; any attempt to engage with issues around food which doesn’t fetishize the words ‘local’, ‘seasonal’ and ‘organic’ is plain wrong. In short, too many of us have mistaken a whole bunch of lifestyle choices for the affluent with a wider debate on how we feed ourselves, when they are nothing of the sort.

We need to get real. The term ‘food security’ is occasionally bandied around, but it has failed to take its place right at the heart of our conversation about what and how we eat, even though it has to be there. Because, be in no doubt: a combination of world population growth – expected to hit nine billion by 2050 – climate change, appallingly misguided policies on biofuels and an ingrained Luddite response in parts of the West to biotechnology risks coming together into a perfect storm; one which will make the sight of young chefs on the telly talking about their passion for cooking and their commitment to local and seasonal ingredients sound like the screeching of fiddles while Rome burns. According to the United Nations, by 2030 we will need to be producing 50 per cent more food, and a system built around that holy trinity of local, seasonal and organic simply won’t cut it.

Indeed, while self-appointed food campaigners are banging on about that, an entirely different conversation has been going on elsewhere, within university faculties and government departments as well as at an inter-governmental level. In that world they use not three words, but two: sustainable intensification. It is about the need to produce more food, in as sustainable a manner as possible, which means thinking about far more than just how close to you your food was produced. It’s about carbon inputs all the way down the production system. It’s about water usage, land maintenance and the careful application of science. According to Oxfam, between 1970 and 1990 global agricultural yield grew 2 per cent a year. Between 1990 and 2007 the yield growth dropped to 1 per cent. We are close to a standstill on producing more food, and that is not a good place to be. In January 2011 the British government’s Chief Scientific Adviser, Sir John Beddington, published a major report entitled ‘The Future of Food and Farming’. It drew on the work of dozens of experts; over 100 peer-reviewed papers were commissioned in its writing. In that report there were 39 references to ‘sustainable intensification’, and the single word ‘sustainability’ cropped up 242 times. Where food is concerned there is a new lexicon, and it has nothing to with farmers’ markets or growing your own vegetables or fruit.

I hate polarized arguments. They serve no one, because nothing is ever black and white. Even while I pick fights with the diehard foodinistas, and I do on a regular basis, it’s obvious to me that there is a lot of good stuff in what they are saying. When they describe the modern food chain and the way we eat its product as being deformed they are absolutely right. A lot is wrong. The problem lies in the solution they propose, which is too often based on a fantasy, mythologized version of agriculture, one that isn’t much different from those lovingly drawn ears of corn slapped on the packaging for Oakham or Willow Farm chickens to suggest their bucolic origins when in fact they’ve been reared in gigantic industrial sheds.

As a newspaper and television journalist I spend an awful lot of my time travelling around Britain (and abroad) finding out how our food is produced. It’s fascinating. I have watched tons of carrots being lifted in the darkest, small hours of the night because, if harvested during the day, they would start to decay under the sunlight. I have dodged fountains of stuff from the wrong end of a cow to help milk the herd on a traditional dairy farm and visited a cow shed that can house up to 1,000 milkers at a time. I have fished for langoustine off the very northernmost tip of Scotland, helped make bespoke salt from the waters off the Kent coast, chosen beef animals for slaughter and followed them to the abattoir so I could witness them take the final bolt. I have driven a £360,000 harvester that vines peas, tried to keep my balance on the slopes of the island of Jersey that give us their sweet, nutty Royal potatoes, and stood in the rafters of an ex-Cold War aircraft hangar atop fifty foot of drying onions. I have even visited a pork scratchings factory and discovered that there is a limit to the amount of pork scratchings an eager man can eat in a day (six packs, as you ask).

From these experiences, and many others like them, I have become convinced that we are disconnected from what real food production means, and therefore afraid of it. We need to understand how it works, be unembarrassed about it, because only then can we genuinely push for the kind of sustainable supply chain which both guarantees quality and that our food will be affordable, though not necessarily dirt cheap. We need to find a way to mate the delicious promise of gastronomic culture with the rather less delicious but equally important demands of hardcore economics. For want of a better word – and there may well be one – we need a New Gastronomics.

So come with me as I show you why the committed locavore, who thinks that buying food produced as close by as possible is always the most sustainable option, has been sold a big fat lie. If what really concerns you is the carbon footprint of your food, then it turns out the stuff shipped halfway round the world may not be the great evil you’ve always been told it is. And because local does not necessarily mean sustainable, it transpires that seasonality is generally about nothing more than taste. Being concerned about how things taste is lovely. Worrying about that stuff is lovely. I do it all the time. But it’s not the same as being good to the planet. I’ll explain why ‘farmers’ markets’ can never solve our food supply problems – indeed are a part of the problem – how little the organic movement has to offer a world looking to produce more food in as sustainable a manner as possible, and why growing your own will never be more than a lovely hobby. I’ll explain why small is not beautiful and why big is not necessarily bad.

You know all those great sacred cows of ethical foodie-ism? Well, I think the moment has come for you to say your goodbyes. Give the old dears a hug. Celebrate how much you’ve shared together. Then wave them off for ever. Because I’m about to lead most of those sacred cows out into the market square and shoot them dead. I’m so sorry, but it has to be done.

People are occasionally surprised that I give a toss about all this. After all, I earn part of my living as a restaurant critic. I swan around on somebody else’s dime, licking the plate clean, trying not to order pork belly too often and writing smartarse things about it all. I have run up three-figure bills for dinner that almost ran to four figures. I have taken plane trips simply to buy a specific brand of vinegar. When my kids want to mock me they recite a tweet – ‘The dish had a hint of rosemary’ – that I swear I never sent, but which very efficiently marks me out as some ludicrous, gourmand fop who obsesses over tiny gustatory details. And all of this is, I suppose, true. I do, after all, earn enough money to be able to pay £31.78 for a chicken just for the hell of it.

But none of that precludes an interest in our food chain in general, and the ability of everybody in our society to eat as well as they need to. Indeed, I would argue that to be in such a privileged position and not to have an interest in these things would be not just obscene but contrary. Challenged once on this point by a journalist who was interviewing me, I compared it to issues of reading and writing. There was, I said, nothing contradictory about having a love for, say, the rich, expansive language of William Shakespeare, and having a keen interest in basic literacy standards in our schools. Indeed, without one you couldn’t really have the other. I think the same applies to food.

So we need to get real about our food. If we really are to shape a New Gastronomics, we need to be honest and brave. And being those things means saying stuff that some people might find unpalatable. Which is exactly what I’m about to do.

2.

SUPERMARKETS ARE NOT EVIL (#u3ed90456-ae32-5e71-a30a-aceafadcf258)

Berwick Street in London’s Soho. It is the mid-sixties and my dad is striding past market stalls laden with fruit and vegetables and meat and fish and bolts of cloth and a whole bunch of other things besides. There has been a market on this site since 1778 and it remains there to this day, albeit much reduced. In the sixties, though, it was a vital part of Soho’s village life, closing the road between the junction with Broadwick Street to the north and Walker’s Court to the south, home then to the infamous Raymond’s Revue Bar and its special brand of nipple-tasselled stripping. Even to this day Soho manages to cling onto its reputation for debauchery. The ‘models’ still advertise their availability by placing in the windows of their dingy flats the sort of red tassel-shaded lamps you’d normally find in a B&B in Torquay; places like Walker’s Court are still lined with sex shops, even if they are a little more glossy and welcoming than once they were. But in the sixties Soho was the real deal, run by Maltese hoods who had the vice squad of the Metropolitan Police in their pay, so they could continue trading merrily in the glorious triumvirate of prostitution, drugs and gambling. If you were in the market for filth, Soho was where you went.

But it was still a mixed economy. In spite of – or perhaps because of – the loucheness, other industries congregated here. Some of the best Italian delicatessens in town were here (and still are), the British film industry had started occupying the warrens of offices not used by the hookers, and many of the shop units were home to the cheaper tailors, serving the theatres of the West End or the kind of clients who liked their lapels just a little too wide. Many of the narrow alleyways were filled with shops stacked with cloths of myriad weights and hues. And, of course, there was the street market.

My father, Des, fitted in well. Although he started his working life as an actor, he had become bored with unemployment and starvation and moved into the fashion industry, and worked now as a PR for the classy mid-market label Alexon. I like to think of him marching down Berwick Street in the ankle-length black leather coat with the shaggy black fur collar that he liked to wear, a cravat tied at the neck, hair swept back, beard trimmed just so. My old man wasn’t in the fashion business for nothing. And so he stops now at one of the fruit stalls to pick up some apples to take to my mother, who is back home looking after my older brother and sister. For we are in the golden age of the local shop and the street market. Self-service supermarkets are burgeoning across the US, but not yet widespread here in the UK. Even the well-known company J. Sainsbury does not generally run supermarkets. They are merely grocers, and when you shop there you must queue at separate counters for meat and dairy and fish and so on.

The fact is that there is nothing much more convenient than this market stall for a man in search of apples. So now Des points to the pristine fruit on the display that he wants. The stallholder turns and starts filling the bag from an unseen box hidden away somewhere underneath.

‘Hang on a moment,’ says Des. ‘I can’t see which apples you’re giving me.’

‘I’ll give you whichever bloody apples I like,’ says the man.

‘In which case,’ Des replies, ‘you can keep ’em.’ He turns and walks away only to hear the stallholder shout after him: ‘Suit yourself, you black-bearded, bollock-faced bastard.’

This is one of the stories with which I grew up; one of those legends that all families have. My dad was a black-bearded, bollock-faced bastard. ‘What was it that man called you?’ my mother would ask from the opposite end of the dinner table, when she thought he was being difficult. And we would reply in unison: ‘A black-bearded, bollock-faced bastard.’

What does this story tell us? Just this: that whatever critics of supermarkets might like to tell you, the alternatives – street markets and local shops – were not, and are not, all run by lovely people, with a genuine interest in and concern for all their customers. They are merely run by people. As they are across the rest of society, some people are lovely. Some of them do genuinely care about the people who shop with them. And some of those shopkeepers and market stallholders are miserable scumbags who are to customer service what napalm is to peace.

Another story, this time from the other side of the debate. I am in the very large Tesco supermarket near my home in Brixton, south London, doing the weekly shop. I am with my son Eddie, who must be 2 or 3 years old; certainly he has not yet started school. Usually he does this shop with my wife, who works part-time, and it quickly becomes clear that he is very comfortable here. For, everywhere we go, the staff say hello to him. It doesn’t just happen once or twice during our hour in Tesco. It happens perhaps eight or ten times: from the shelf stackers to the women on the deli counter to those working the checkouts. All of them know Eddie by name and have a few words for him. I am intrigued by this and so begin to notice something. We are not the only people this happens to. There are conversations between staff and customers going on all over the place, and they are not simply about which aisle the dried fruits are located on. The staff here know their customers, which really isn’t surprising, because almost all the employees come from the heart of this community.

So what does this second story tell us? Just this: that whatever critics of supermarkets might like to tell you, they are not all bland, anonymous, swollen warehouses disconnected from the neighbourhoods in which they sit. Of course, some of them might be. Some of them might feel like waiting rooms for death, just as some local shopkeepers are not very nice. But the assumptions we make about these enormous shops from which we buy the vast majority of our food simply do not stand up.

We forget very easily just what life was like in the World Before Supermarkets. I am old enough to remember as a small child being taken on the family food shopping expedition to J. Sainsbury’s in Kenton, north-west London, and the way we really would move from counter to counter. It was my job to say ‘six wings and six legs’ to the man at the butchery counter, so he could fill our weekly chicken order. It was cute. It was adorable. It was one of the ways in which my mother made the whole damn experience in some way bearable. The thing at the chicken counter broke up the tedium. Our bread came from the baker’s on the corner by our house, our fruit and veg from Robert the Greengrocers across the road, and any tinned goods from a small shop called Walton, Hassle and Port ten minutes’ walk away. It sounds lovely, doesn’t it, this patronage of local and small businesses, this tight web of inter-dependent relationships? And we did like the people involved. But gathering everything that the family might need for the week was a tiresome job.

My mother is gone now, but her close friend Carole Shuter, who also had three small kids in the sixties and seventies, remembers it in detail. ‘Oh God, it was a whole morning’s outing,’ she told me. ‘You’d have to clear the diary. I remember the Sainsbury’s thing very well, the way we had to queue half a dozen times and pay separately at each one. People romanticize things like butter being sold in blocks and you asking for a bit to be cut off, but you wouldn’t romanticize it if you had to do it every bloody week. It takes so long.’

Alan Sainsbury, the family-owned firm’s head, had come across the notion of self-service supermarkets in the US in the years immediately after the Second World War, and imported the idea. The company opened its first self-service branch in Croydon, just south of London, in 1950. Still, the roll-out didn’t begin in earnest until many years later, after Sainsbury’s went public in 1973 with what was then the biggest flotation in British stock exchange history. It didn’t reach our corner of London until the early seventies. (The last counter store hung on, in Peckham, until 1982.)

‘The first proper supermarket was a complete revelation,’ Carole says. ‘It was bloody marvellous. People are too quick to demean modern developments like that. They have no idea what it was like before. No idea at all.’

The point is that women like my mother and Carole had far better things to do than waste whole mornings of their week just getting the food shopping done. In Felicity Lawrence’s highly regarded book Not on the Label, a searing critique of Britain’s supermarkets, first published in 2004, she writes about the joys of shopping locally; of how it could be a bonding experience for her and her young family; that there was always time for such pleasures.

Really? Many of the generation of women who came before Felicity Lawrence that I talked to about this regarded it as a retrograde step: an attempt to cast women in a role they had fought throughout the second half of the twentieth century to throw off. One went as far as to say to me that buried within the anti-supermarket argument was one that sounded profoundly anti-woman because it was always the women who were burdened with the job of schlepping around the shops, which in turn made the notion of their having a full-time profession all but unsupportable. Whether the arguments around supermarkets really can be cast in these terms – a modern embarrassment about the idea that such things as food shopping should ever be seen as women’s work do kick in here – there is no doubt that, by reducing the number of hours needed to get domestic chores done, there was more time for other things. And thank Christ for that, because otherwise the economics of domestic life would have been completely unsustainable.

There are, of course, the economies of scale. Supermarkets make things cheaper. They just do. When you have more than 2,500 stores, as Tesco does, or over 1,000 like Sainsbury’s, you have serious buying power. Over 80 per cent of the retail food market spend is concentrated in the hands of the big supermarkets and, whatever the downsides of that, it has, historically, led to cheaper food. In the early post-war years it took over a third of average salary to pay for the food shop. Today it is just under 10 per cent. Or, to put it another way, you had to work until Wednesday morning to pay for the family’s weekly shop; now you’ll have earned enough by some time just after noon on Monday. And that’s not because salaries have increased enormously, compared with all the other costs we face; quite the opposite.