По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

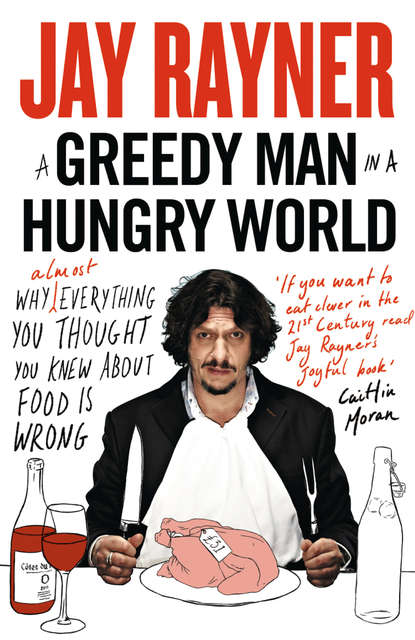

A Greedy Man in a Hungry World: How

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

That was why I was there: to see the situation for myself, to write and broadcast about it.

It was also why I suggested to some of the team I was travelling with that we should go for a Chinese at the restaurant across the road. I told them my story about eating Chinese food in odd places, and about how I’d eaten awful Chinese meals in Greece and Turkey and France. And I laughed and said what we needed was a totally surreal experience, so let’s go to that dimly lit place across the road, the one with the hanging Chinese lanterns and the open walls with its views out over the city.

But it wasn’t true. What I actually needed, what I craved, was a bit of normality, and in the flavours of Chinese food that I knew so well I felt I could locate that.

Because what I was seeing during my trip wasn’t normal. It felt a very long way beyond normal. I was wrong, of course. It was only not normal for me. For the people I was meeting in Rwanda who were living these lives it was entirely normal. That was the real tragedy.

Rwanda has food. The place looks like it is built of the stuff, the deep red earth heavy with fruit and grain and leaf. It is called ‘the country of a thousand hills’ – a gross underestimate – and it looks like every inch of those hills is under cultivation, from the prime plots at the bottom of the valleys to the very peaks for the poorer landowners, who must exhaust themselves climbing up there before they can even start work. The land is laid out in a tight patchwork of fields which, to the average grow-your-own fanatic in the West, must be a unique kind of gastro-porn. Look at the hand-tilled land! Gawp at the rows of beans, the tall stalks of maize, the cassava and sorghum and groundnut crops! Gasp at the yams, the tomatoes ripened to the deep red of a postbox. Oh my! What a perfect small-is-beautiful world. If only Kentish Town could look like this. If only we all grew our own and abandoned supermarkets and fed ourselves like the Rwandans, who are so much closer to the earth.

Or not quite. There is an ugly reality hidden by all this verdant loveliness. Rwanda may be very fertile but it also has lots of people. It is the most densely populated country in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 400 souls per square kilometre (and, in places, over 700). By contrast, the UK has a population density of just over 250 per square kilometre, while the United States has a mere 32. Although the inter-tribal hatreds behind the genocide are well known, some theorists, most prominent among them the Pulitzer Prize-winning academic and writer Jared Diamond, have described the events in Rwanda as proof positive of Thomas Malthus’s theory that lack of resources would keep the human population in check. In short, they say, underlying the genocide was a scarcity of food and land to grow it on. If true, it’s further cause for concern: the population of Rwanda is now higher than it was before the genocide. Certainly the battle for those resources is fierce. Nearly 60 per cent of the population have less than half a hectare to cultivate.

According to figures from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the average Rwandan gets by on 2,090 calories a day. The average British person consumes 3,450 and the average American 3,750. Around 9.5 per cent of the Rwandan diet is protein, of which just 0.9 per cent comes from animals. In both the UK and US, 12.1 per cent of the diet is protein and more than half of that comes from animals. Around 38 per cent of the diet in the UK and US is fat; in Rwanda it’s just over 20 per cent. Rwanda does not have an obesity problem. Instead it has a population problem.

Not that you need to be bombarded with facts and figures to get to grips with Rwanda’s challenges. You can see it everywhere. One day we drove out from Kigali in our Save the Children 4x4s, the vehicle of choice for celebrity poverty tours. At first we were on solid, metalled roads paid for with international aid – half the country’s budget comes from donors – and then on roads of rutted earth. There were the hills to look at and the fields to admire, for it is a jewel of a place. But most of all there are the people, and so many of them so young. Half the population is under 18 years old, and while there are efforts to get them into school many are still not in full-time education. They were hanging out on the grass verges watching the world go by, or waving furiously at our cars as they passed. There was an overwhelming sense of a horde of humanity at rest (though across the fields we could also see the silhouettes of women, stooped over their crops as they worked. It was almost always the women, not the men).

We visited a new health centre, built by the charity, on land punctuated by outcrops of black volcanic rock from the smouldering volcanoes that ring this part of the country. Mothers sat with their tiny babies, waiting patiently for their children to be weighed, part of a project to monitor their progress since being identified as malnourished. Measuring bands were wrapped around the kids’ spindly arms to check if they were filling out. If their arms were found to be in the green area of the scale they were fine. If they were in yellow, as many were, they were chronically malnourished; if in the red, the situation was acute. Rain battered down on the veranda roofs and the air smelt heavily of vegetation on the turn.

I talked to 23-year-old Josephine, who was sitting with a 2-year-old and a 1-year-old on her lap, the two fighting over her breasts for feeding rights as she talked. She seemed oblivious to the lifelong sibling rivalry being born on her knees. She was small and thin with high cheekbones and a long slender neck and dressed in vivid wraps of fabulous prints; these were, I was told by my guides, probably her Sunday best, put on because she knew we were coming. I was wearing tired linen trousers and a saggy jacket. I felt I should have made more of an effort.

A health visitor had come to her house a kilometre or two away to tell her there was a problem with her kids, Josephine said. I asked if it was upsetting. ‘Not really. They gave me the supplements.’ They were fed on Plumpy Nut, a protein and fat-rich peanut paste, fortified with vitamins, foil-wrapped packs of which she received at each visit. Gathering enough food for her family – she had other children at home – was tough. ‘I have no land and I am the only one who gathers food. I get it by working in other people’s fields.’ So why did her children become malnourished? I asked.

It was a stupid question, but I was flailing around, trying to find the right way to talk about what sounded to me like any parent’s worst nightmare. Before becoming a restaurant critic I was another sort of journalist, one who spent too much time writing about the evil that men do. I covered murders and terrorism and politics and poverty. Worst of all were the child abuse cases, for I found in myself the ability to project the stories I was hearing onto my own children, to swap one set of faces for another. One night after a day spent sitting in court listening to the wretched and banal details of acute neglect, of small children left to rest in their own faeces, ignored despite their calls for help, I went home and washed my own eighteen-month-old so fiercely in the bath I gave him a rash. My child would be clean. My child would be cared for. I needed to wash out the dark stain of those stories.

This felt similar, and yet I was required to engage. I was required to find a language. So then, why did Josephine’s children become malnourished? She looked at me blankly and, through the translator, said, ‘Because I cannot get enough food.’ I nodded solemnly and wrote the words down in my notebook – ‘cannot get enough food’ – knowing they were the answer to a very stupid question.

In another part of the centre we met a mother who had only given birth a couple of days before, her newborn son in her arms, tightly swaddled. He stared up at us, wide eyed and baffled, and we made the right noises about how beautiful he was and how I hoped the delivery had been OK and how helpful a health centre like this must be to mothers like her. Then I asked his name. She smiled thinly and said something to my translator. By tradition, he told me in turn, they did not give babies names until they were eight days old, ‘because they need to see if the baby will live’. I scratched more notes on the bloody obvious in my notebook. It was all part of the same story. It was all about maternal malnutrition as much as it was about child malnutrition. It was about the creaking arithmetic of life and death here on Rwanda’s fecund, pulsing earth.

The problem was not simply lack of land, though that was a big part of it. The price of staple foods in the markets here had, as everywhere else around the world, shot up. There didn’t appear to be a shortage of food to buy. In the central covered market in Kigali I saw heaps of flour and potatoes, and piles of shiny aubergines of a quality that would make a London restaurateur weep. It was all there. It just cost too much. The impact was twofold. First, there was the obvious problem that those right at the bottom of the economic heap simply couldn’t afford to supplement their diets with extras from the market because of the global price rise. And then there was a curious impact: instead of feeding all their crops to their kids some subsistence farmers had a price incentive to sell them for money, because of those price rises, earning cash which they might then use to buy things other than food, often for the best of reasons. A farmer might choose to buy a kerosene lamp, I was told, so his kids could carry on with their homework once the sun had gone down, education being seen as a route to a better life. Poor families in Rwanda, I learned, were likely to fall back on a staple like cassava, a starchy root that could be ground down into a flour to make a dry doughy paste. It’s about as bland nutritionally as it tastes. Imagine a soft dough made from cardboard. Then remove any of cardboard’s grace notes. Cassava does boast calories but it is almost completely nutrient free. Eat too much of that and you would soon have a vitamin deficit. The Rwandan diet is in need of a serious overhaul.

We moved on to a village where the houses had mud walls and mud floors and most of the cooking was done inside, over open fires so that the high tang of soot hung over the room. Outside the house representatives from the Rwandan health ministry, the health centre and Save the Children, the standard entourage for a visitor to the country with a media profile they might be able to work to their advantage, stood around tapping away on smartphones and making calls. Here, as elsewhere in Africa, the mobile phone network has revolutionized communication.

Outside the house we were firmly in the twenty-first century. Inside we had slipped backwards into what felt like a pre-industrial age. I was introduced to Leonie and Immaculate, both widows, both mothers of six, each of whom had children displaying the most acute symptoms of stunting. Immaculate’s 9-year-old daughter, Claudine, was particularly affected. She had learning difficulties and was very small for her age, and stood curled into the folds of her mother’s long skirt, staring out at me from a domed, slightly swollen head. She had scant hair, a classic sign of malnutrition. ‘I was surprised when they told me,’ Immaculate said, ‘because I did my best to feed my children. I thought it was some other form of disease.’

At another home I met Vestine, who had lost three pregnancies because she was malnourished and forced to work in the fields too close to her due date. She and her husband, Claver, had a daughter who was 8, plus eighteen-month-old twins. Their daughter in particular was showing symptoms of malnourishment. When Vestine led me into the house to show me what she had to feed them with, it was easy to see why. She was doing her best, but the pile of beans, potatoes and green leaves defined the word meagre.

I was accompanied by a producer from Save the Children and a cameraman, who had passed most of his career in war zones – Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq – and now liked to spend some of his time working for charities. We were shooting a short film about my trip that would go up on the web and they asked me now to do a piece to camera about the situation in which Vestine found herself. I knew the film would be seen by lots of people. I knew I was doing what the charity asked of me. I knew that it would highlight a vital and important issue. I knew an awful lot of very obvious things.

But as I squatted down by Vestine’s open fire, and felt my knees creak and saw my linen trousers stretch tight across my bulked-out, varicose thighs, I couldn’t help but feel a certain impotency. What in God’s name did I think I was doing here?

I have experienced poverty, but only once and only then for about thirty-six hours. It’s not to be recommended. It was at the end of a solo back-packing holiday across Greece and Turkey. I returned to Athens, where the trip had started, with a couple of days left until my flight home and barely enough cash for anything more than a plot for my sleeping bag on the roof of a hostel, and the bus fare to the airport. I passed the time lying in the shade on a bench in a park, reading a book I had already read and trying not to think about how hungry I was. When I finally boarded my flight home, I fell upon the tray of airline food with a genuine enthusiasm, the one and only time that has ever happened.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: