По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

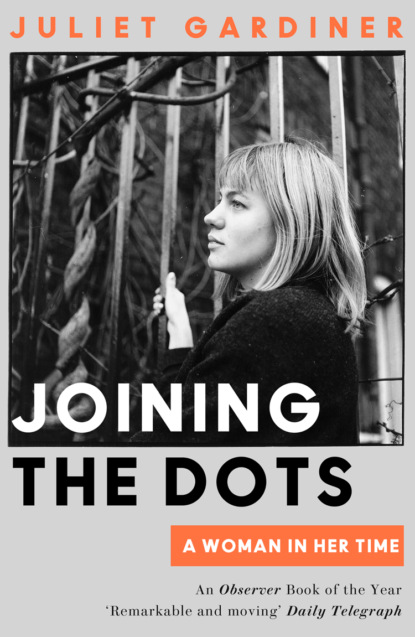

Joining the Dots: A Woman In Her Time

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Until the 1920s, the adoption of babies and children had been a casual, informal affair with no legal process involved. It was not until 1943 that it became compulsory to register adoptions. Children were regarded much as chattels: the responsibility but also the property of those who had created them. The babies of unmarried mothers might well be absorbed into the family, the mother stripped of her maternal status and passed off as an older sister or an aunt. Or a baby might be handed on like one of a litter of puppies or kittens in excess of requirements, to a more distant relation, friend or neighbour who didn’t have children of her own and wanted a baby, or to a motherly soul who already had such a large brood that one more wouldn’t make much difference.

The writer Ian McEwan’s mother handed her baby over at Reading station to a couple who had answered a newspaper advert. Later she bore two more children, one of them Ian. And in 1938 the mother of the future children’s author Allan Ahlberg, carrying a string bag containing bootees, a baby’s bottle and a shawl, had travelled from Paddington to an orphanage in Battersea where she ‘signed a couple of documents’, the infant Allan was handed over to her and she returned to Paddington where her husband was waiting, clutching ‘her secret/ On her lap/ From all the other passengers/ All the way back’, and the new family caught another train home to Oldbury in the Black Country.

Many of these informal arrangements probably worked out reasonably satisfactorily for the child and its new family, but there were sensational reports in the newspapers from time to time about ‘baby farming’, when a usually middle-aged woman who had advertised in a local newspaper offering to provide a home for a baby for a cash payment, was subsequently found to have starved, neglected, beaten or even killed babies in her care. The most notorious case was that of Mrs Amelia Dyer of Reading who was hanged in 1896 after being convicted largely on the evidence of her daughter of strangling a baby and dumping its body in the Thames. The police estimated that Mrs Dyer had done away with at least twenty and possibly as many as 200 babies that had been entrusted to her care by their mothers.

Throughout my childhood, a wax model of the fearsome-looking Mrs Dyer standing in the dock of the Old Bailey could be seen in the Chamber of Horrors in Madame Tussauds on the Marylebone Road in London. It terrified yet compelled me, and lying in bed at night I would conjure up that monstrous black-clad figure with prominent teeth and a cold, sightless gaze. This would alternate in my imagination with G. F. Watts’s melancholy painting Hope (1886), a large reproduction of which hung in our hallway at home. This gloomy allegorical depiction of a blind woman sitting on a globe, her eyes bandaged as she strains to hear the faint music of the broken lyre she is holding, haunted me for years, and I am at one with G. K. Chesterton who wrote that a more appropriate title would have been ‘Despair’. To me these were the two most frightening images possible, and their nightly evocation, I imagined, would be a talisman; the equivalent of a lucky rabbit’s paw, which would somehow keep the dark forces of night at bay.

The desperate plight of an unmarried mother and her intense desire for secrecy would mean she was in no position to enquire too closely into the circumstances of the person to whom she was handing over her infant, and there were no legal requirements on either side, just an implicit understanding that the mother would not seek to reclaim the baby she had effectively sold, nor the ‘adopter’ seek to return it. The drawbacks to this casual exchange were addressed to a small extent in the first Infant Life Protection Act of 1872, which required that anyone receiving two or more infants under the age of one (eventually raised to seven by the Children’s Act of 1908) for ‘hire or reward’ was obliged to register her address with her local authority, or in the case of London, with the Metropolitan Board of Works. But these safeguards were neither effective nor enforced.

Concern sharpened after the First World War when there was a positive glut of babies in need of care, either orphans, the progeny of widows whose husbands had been killed fighting, or babies born out of wedlock. Around 42,000 of them – ‘children of the mist’ – were in this last category at the war’s end. This figure was not reached again until the year of my birth, towards the end of the Second World War, when the rate of illegitimate births leapt from 36,000 in 1942 to 43,000 the following year.

However, moves to regulate adoption practices in the interwar years came not from the government but from voluntary organisations, following the example of Clara Andrews whose work in Exeter with child refugees from Belgium during the First World War had convinced her that there was a need for some sort of a broker between unwanted children and would-be parents. The National Children’s Adoption Association (NCAA) was intended to do just that: those wishing to adopt a child were given full details of the child’s background and medical history, while a certificate of health and references were required both from the child’s parents and from the putative adopter, and similar procedures were also the practice for Dr Barnardo’s and other charities which arranged for the permanent placement of ‘unwanted’ children with families, or very occasionally with single women.

Nevertheless, throughout the interwar period adoption was regarded as a last resort, even in the case of the unmarried mother. It was argued that all should be done to help her keep her child rather than have it adopted. The National Council for the Unmarried Mother and her Child, set up in 1918, insisted that this was generally the best solution and that more support should be given to the mother to enable her to keep her child. This view was influenced by a belief in the strong biological bond between a birth mother and her child, and by a concern that potential adopters could be impulsive and sentimental in their desire for a child and might not have fully thought through the responsibilities and stresses of parenthood. If a young woman could just hand over her baby for adoption and thus relieve herself of any responsibility for it, it was deemed likely that she would not learn her lesson and moral turpitude would go unchecked. Moreover, many eugenicists considered that personality traits were genetic and likely to be inherited: they would ‘out’ like physical characteristics such as blue eyes or blond hair. So an infant born out of wedlock was seen as preordained to have a not entirely reliable moral compass: as clear as an unsightly birth mark, an irremovable moral stain tainted the innocent bastard.

Most people looking to adopt wanted a no-strings orphan of two or three years old, whereas in fact most children on offer were illegitimate and most of these were babies. In her book on adoption (A Child for Keeps), Jenny Keating explains the preference at this time for a toddler rather than a newborn as proof that the child came from sufficiently good stock to survive infancy, since its genetics, its inborn nature, would be the defining characteristic in its development. Subsequently, with more awareness of psychoanalytic theories’ emphasis on the dominance of nurture over nature, potential adopters were more attracted to the idea of a newborn infant as being a tabula rasa on whom they could imprint their own ideas and values.

Indeed, over the course of the twentieth century, the notion of intuitive mothering was increasingly challenged by the popularity of manuals from a growing number of experts in both child health and child psychology. From Truby King, with his belief in fresh air and rigidly regulated feeding and cuddling routines, to the altogether more relaxed and more permissive Dr Benjamin Spock, who encouraged mothers to trust their babies’ instincts, or on to the middle-way Penelope Leach or the draconian, childless Gina Ford, the zeitgeist of the nursery had changed. Mothering was not purely instinctive: it could be learned, it had a scientific, research-based dimension. The effect of this could hardly fail to narrow the gap between the ‘natural’ or birth mother and the adoptive mother, since both could be seen clutching the same latest fashionable mothering manual, both as perplexed by questions of babies sleeping on their back or front, of yes or no to dummies, the right age to potty-train, how to deal with the tantrums of the ‘terrible twos’.

A newborn baby being brought home from hospital was also a simulacrum of the natural arrival of an infant, its provenance obscured in the soft folds of the lacy white shawl in which it was likely to be enveloped. This was apparently particularly pleasing to middle-class adopters, for whom the unpleasant miasma of the ‘baby farm’ still obstinately tended to cling to the idea of adoption. In any case, the appearance of a toddler in the household of a childless couple announced in a starkly obvious way their failure, with no IVF or other aids to fertility available, to produce a child in the time-honoured way, whereas the arrival of a newborn baby was a more ambiguous event. If the arrival of a child signalled a ‘normal family’, why would adoptive parents wish to disrupt that conventionality if they could avoid it by proclaiming to the world that their family was ‘different’, their child a foundling of uncertain pedigree?

II Arrival

Given my age, I did not, of course, arrive at my new home wrapped in a shawl but, I was told – though I have been unable to find any photographic corroboration – dressed in a tweed coat with a velvet collar, tweed bonnet and tweed leggings (which were not like today’s leggings but more like trousers with elastic that went under the shoe). I was, I think, about two and a half years old, the paperwork required by the 1926 Adoption of Children Act completed, and only a short court hearing in front of a magistrate still to come, followed by the issue of a shortened birth certificate. This was half the size of a usual one and with no space for the name, occupation or parish of either parent, but was nevertheless a legal document of irrevocable status that gave an adopted child the same rights and legal status as a natural-born one when it came to inheritance. It was a ‘fresh start’, ‘a new page’ in my life. And stark evidence for evermore that I had been adopted.

I was illegitimate, as were more than 40,000 babies born during or just after the Second World War. I was adopted from the Church of England Incorporated Society for Providing Homes for Waifs and Strays (subsequently the Dickensian evocation of Waifs and Strays was dropped in favour of the simple ‘Children’s Society’), where I’d been placed when I was probably about two months old after the original adoption arrangements made at birth had fallen through, since a severe case of bronchitis suggested that I might have a congenital chest condition and thus could not be granted the clean bill of health required for the adoption to go ahead. I believe it is the same with cows: they have to be certified fit before they can leave the cattle market for new byres.

A warning here. ‘All Cretans are liars,’ said the Cretan. ‘All adoptees are fantasists,’ said the adoptee. Certainly I am; a natural spinner of a skewed family romance. I not only exist in a personal historical void, I am a void, officially a filius nullius. I have no given past, no known sidebars. I am obliged to answer ‘I don’t know, I am adopted’, when asked if there is a history of diabetes, or high blood pressure, or insanity, in my family. Thus, it seems not unreasonable that given a blank sheet of paper, a true tabula rasa, one is unable to distinguish, or chooses not to distinguish, fact from fiction in the narrative of one’s life. I fill in the void, inscribing the abyss in ways that make my free-floating self seem more interesting, more desirable, by the construction of grander birth parents and more intriguing circumstances surrounding my birth. If I am rootless, why not sink my roots in the richest, most friable soil possible?

I sometimes say now that I am not entirely sure what the truth about me is, and that at least is true, but that is because over the decades, my memories and fantasies about my memories have calcified with what little I have been told, and that edifice is now the truth and I have no certain way of dismantling it. I may even occasionally find myself adding another layer or smear of obfuscation.

Under the terms of the 1926 Adoption Act, adoption had been intended to be an open process; the adopters’ names and addresses appeared on the consent form the parents (or more likely the mother) who gave a child up for adoption signed to enable this. But this transparency could prove to be an inhibition to would-be adopters who wanted the child they had adopted to be considered to be theirs, just as a birth child was. They were not prepared to trade the ambiguity of their family’s formation for legal regulation. They preferred their unregulated parental status to taking the possible consequences when not only the adopted child, but the world at large, could know the truth. This was considered particularly true of ‘villadom’, presumably the lower middle classes who guarded their privacy fiercely from neighbours ‘poking their noses into other people’s business’. But some working-class parents stated that they had chosen to move to another town to obscure the knowledge of their status as adoptive parents, whilst ‘some hunting people’ (presumably upper-class) admitted that ‘if we had to go into court, even a magistrate’s room to have this legalised, we would not do it. We would give up the child rather than that it should be known that it came through a society.’

This blotting-out of an adopted child’s origins was concretised by the 1949 Adoption Act, which raised a high wall of secrecy. It decreed that the birth mother would not in future be informed of the name of her child’s adoptive parents nor where they lived: in future, only a serial number would appear on the adoption papers, in place of the previously uncoded information. The sponsor of the bill in the Lords, Viscount Simon, insisted that ‘it was in the interest of the child that the birth mother should not haunt the home of the new family’. An iron curtain was to be dropped between the natural and adoptive parent so that it would be extremely difficult for a mother to trace the child she had relinquished.

However, despite this officially erected fence, it was increasingly accepted that it was unrealistic to imagine such an intimate secret could be kept in perpetuity. Furthermore, it would be traumatic for a young person to find out, perhaps at puberty, that the people he or she had regarded as its ‘natural parents’ were in fact not biological relations. The rock on which the young person’s identity had been grounded could crumble; they would be most likely to feel vulnerable, deceived and betrayed in the most fundamental manner. What else in their young lives was not true? Where did veracity lie, if not with the person they believed had borne them? To avoid this trauma of exposure, agencies strongly advised parents that their children should be told that they were adopted as soon as they were able to comprehend what that meant – somewhere between three and six years was reckoned to be optimum.

I can’t remember when I was told that I was adopted, but I must have been quite young. However, once this information had been imparted, it was never referred to again and I was discouraged from asking more or alluding to the fact. Once, after being bought a doll in a toyshop, I remarked, ‘She’s adopted like me’, and was hustled out of the shop by my mother who said sharply: ‘We don’t talk about that.’

If I ever asked who my birth mother was, my adoptive mother would reply: ‘You don’t need to know that. You are ours now.’ This seems reasonable since in the immediate postwar world ‘birth mother’ was not a phrase in common currency, rather it would have been ‘real mother’, which must have been immensely hurtful to a woman who had done everything for the child short of pushing her out into the world. Who was the ‘real’ mother in this context? The bearer or the carer?

I understood, and I was prepared to believe – I think – that I was more special because I had been specifically chosen; rather than just slithering into my mother’s life with no chance of return or refund. I was told that I had been picked out because I had blue eyes and a nice smile – and in any case two-thirds of those wishing to adopt expressed a preference for a girl.

But what I did find very hurtful for many years were the veiled allusions, the snide remarks – ‘I’m afraid that you are fast growing up to be like your [birth] mother’ – with no more insight as to what that meant and why it was something I should not want to happen. And worst of all was my mother’s occasional taunt of ‘If only you knew who your father was …’, and no matter how much I begged to be told, my mother’s lips would purse into a stony silence leaving me none the wiser as to whether he might have been the Duke of Windsor, General Montgomery, or an American GI ‘over here’ to prepare for D Day (as I often fantasised).

My adoption was not terribly successful. My mother and I were a disappointment to each other. I was not the daughter she had hoped for, nor she the mother I would have chosen if such a reversal of choice had been on offer. She was, like so many mid-century women, I suspect, disappointed by life. She was of working-class origin but had a burning desire to be middle-class, with all the attributes and appurtenances that implied. Her father had been a railwayman, a signal keeper, I think, living in Walton, near Peterborough, who was dead before I came into the lives of Mr and Mrs Wells. Her mother, of whom she had been very fond, was also dead. My maternal grandmother had been nursed by her in our house in her dying months, though I cannot reliably remember her. I suspect that my mother was deeply saddened that she seemed unable to recreate with me the mother–daughter bond she’d had with her own mother.

My mother (Dorothy Fanny – known as Dolly – whose second name never ceased to make my children laugh) had wanted to be an infant school teacher, but that was an aspiration too far for a working-class girl in the aftermath of the First World War, educated only to the age of thirteen at an elementary school. I am not sure what she did for a living before she married; she was always very cagey about that, but I suspect that she was in service. Not in a grand Downton Abbey sort of a house with its life below stairs, its ‘pug’s parlour’, its ladies’ maids, its grooms and butler, but rather as a ‘cook general’, that loneliest of lives, the sole servant in a middle-class suburban villa, ‘doing’ for two bachelor businessmen, cleaning, shopping, cooking plain meals, washing and ironing. A housewife in all respects but those that one might think had meaning.

Things had brightened for her when she met my father, Charles, who was just a rung above her in her carefully calibrated social ladder. He had the ambition to be a doctor, but before he achieved medical school his father, a heavy drinker and, I suspect, a wife-beater, had died and that put paid to his ambition, since his wages were needed to help the family’s meagre income. My parents married in 1927, she in a drop-waisted, flapper-style cream silk dress and narrow satin T-bar shoes. A similar miniature shoe in silver, filled with wax orange blossom, and a silver cardboard horseshoe topped their wedding cake. My parents kept this souvenir, together with a collection of heraldic Goss china and a glass tube filled with layers of different-coloured sand (from Alum Bay in the Isle of Wight, where they had spent their honeymoon), in a glass-fronted display cabinet in the dining room throughout my childhood.

After their wedding, my parents set up home in privately rented accommodation (as most people did in the late 1920s) near Watford in Hertfordshire, moving a few miles to Hemel Hempstead when my father got a job in the local Borough Surveyor’s department. Eventually he would build – or customise the plans of a spec builder – the house in which they would live for some forty-five years. So in the mid-1930s my parents became proud home owners (or rather mortgage holders) of a pebble-dashed detached house with a rectangular garden back and front.

It was some time before they got round to starting the process of adoption. When I once asked my mother why she hadn’t had a child, she replied that the egg ‘kept coming away’, by which I presume she meant that she had had a series of miscarriages. Maybe hope ran out in the early days of the war. Maybe my father needed persuading – though I doubt that. Maybe the vicar had suggested it as a distraction from the nervous headaches my mother suffered from and a Christian gesture towards a cast-out child. They were quite old – in their late forties, which seemed much older then than it does now – to embark on first-time parenthood with a young child. And they were – unsurprisingly – stuck in their ways, rigid in their routines, unused to the noise and tumbling of childhood. ‘Steady, steady’, was the admonition most heard in our house, according to the recollection of childhood friends invited to tea.

I was frequently reminded that I was lucky to have been adopted, otherwise I would have ended up in an orphanage, or a children’s home. After all there were so many illegitimate babies on offer at the end of the Second World War – a regular ‘baby scoop’ the Americans called it. The uncertainty, danger, intensity and impermanence of wartime was conducive to unlikely liaisons and fleeting couplings, since men and women moved around more in wartime, posted away from their home surroundings to places where they knew no one and sought comfort or adventure. Some babies were born to single women, others to wives who’d had an affair while their husbands had been away fighting abroad or working elsewhere in war production. In some cases, the returning husband was prepared to forgive his wife’s ‘lapse’ on condition that the consequence was adopted. However, the novelist Barbara Cartland, who had advised WAAFs on welfare and personal problems during the war and turned to counselling returning war veterans after the war, advised men to try to accept this situation. ‘At first they swore that as soon as it was born the baby would have to be adopted, but then sometimes they would say, half shamefaced at their generosity, “the poor little devil can’t help itself, and after all it’s one of hers”.’

As I grew up I did indeed regard myself as fortunate to have been adopted. It sounds an unkind, and certainly an ungrateful thing to say, but I came to rejoice in my status as an adopted child. I was not ‘one of them’, I realised as I grew up. The traits that I found difficult or irritating about my mother were characteristic of her, not part of my make-up. I was a superior being, I conjectured, since I had no evidence; certainly the child of a very clever and beautiful mother, in the temporary custody of some rather banal earthlings. I did not expect to be reclaimed by this exotic yet warmly maternal creature, but this belief would eventually give me the confidence to strike out a new route to fulfilment and happiness, far from the high laurel hedges, Rexine furniture and conversations that invariably failed to move beyond remarks about the weather or comments on the food: ‘This lamb’s not as tender as last Sunday’s joint, Dolly.’ All I had to do was bide my time. Which is essentially what I did throughout my childhood and school years, waiting, confident that being grown up would change everything.

Despite a more relaxed attitude towards the ‘accidents’ of wartime, opinions hardened again during the postwar years of dreary austerity. Throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, the ‘shame’ of illegitimacy still persisted, with the fear of a missed period blighting many young girls’ lives. Middle-class pregnant daughters were invariably sent by private arrangement to mother and baby homes, usually in the country but certainly far from their own neighbourhoods. There, they would give birth, and the baby would usually be taken for adoption, sometimes against the wishes of the mother, who would return to her family home and her old life after ‘a holiday with relatives’ or ‘a temporary job abroad’. She would slip back into her former life as if nothing had happened. But it had, of course. Regardless of how much she accepted that this was the only realistic course, the bereft mother had suffered a profound loss, and many women found themselves forever unable to forget the babies they had carried for nine months, given birth to, nursed for weeks, only to have the infant taken away.

For those without such resources, relatives or charitable institutions were called upon. ‘Being pregnant and unmarried in 1950 was something you wouldn’t wish on your worst enemy,’ wrote Sheila Tofield, who worked in the typing pool of the National Assistance Board in Rotherham. To her surprise and horror, she recalled in her 2013 memoir The Unmarried Mother, she found she was pregnant after sleeping with a former colleague who washed his hands of any responsibility. ‘If people did something that went against the social norm in those days, no one sympathised or tried to understand. It was simple: there were “nice girls” and there was the other sort, who brought shame on themselves and their families. And that was the sort of girl I had now become.’ Sheila Tofield’s brother effectively disowned her, while her mother was apoplectic at the ‘disgrace’ she had brought on her family. Her response was to half fill a tin bath with boiling water, command her daughter to climb in, and hand her a quarter-bottle of gin, instructing her to ‘drink this and then go to bed’.

When this abortion attempt proved unsuccessful, Miss Tofield wrote to Evelyn Home, the ‘agony aunt’ at the magazine Woman, explaining that she was unmarried and pregnant and her mother was adamant that she could not keep the baby and it would have to be adopted. The reply was the standard one: she should get in touch with an organisation run by the Church of England, in this case in Sheffield. The woman who interviewed her told Sheila that she would be sent to a mother and baby home in Huddersfield:

‘You’ll go there for six weeks before your due date and remain there for six weeks after the birth. When the baby’s born, you’ll take care of it until it’s adopted.’ She didn’t give me any details of what she called ‘the adoption process’ or anything about how the people who would become the parents of my child would be selected. And I didn’t ask. I knew that what I had done was ‘wrong’ and I didn’t expect sympathy or kindness from anyone, or to be offered a choice about anything. I was just thankful there was somewhere I could go to have the baby before I went home again and tried to pretend that none of it had ever happened.

So on the morning of the day she had hoped would never come, Sheila Tofield packed a small case and caught two buses to Huddersfield. ‘I was setting out on a journey I didn’t want to make, to a town I didn’t want to go to, where I’d do something I didn’t want to do.’

It was not until the more permissive 1960s that the stigma of illegitimacy began to ebb, and a decisive moment came in 1975 when transparency triumphed. Legislation made it possible for an adoptee to obtain a copy of his or her full birth certificate from the General Register Office; this gave the name and address of the birth mother, and her occupation at the time of her child’s birth, but in the case of unmarried parents, not of the father unless he chose to be named.

I have never tried to track down my birth mother, though over the years I have gleaned from an aunt who thought I deserved some (but not much) information about my identity the fact that she was Italian – probably from northern Italy. Whether she was a student over here when war broke out and elected to stay, or was interned in 1940 after the fall of France when Mussolini joined the Axis powers (unlikely but not impossible), or whether she was of Italian extraction but her family had lived in Britain for at least a generation, I don’t know.

When I was a young child I think I was wise enough to realise that this glamorous, brilliant mother I had conjured up was most likely to be an illusion. After all, my friends’ and neighbours’ mothers were much like my own, with their greying, tightly permed hair, felt hats, slightly shabby clothes and sensible shoes. (Clothes only ceased to be rationed in 1949 and the wartime ‘make do and mend’ ethos was still prevalent among British women.)

As I grew up, I felt I had no need for another mother, since the one I had already had proved less than satisfactory in my view. Soon I had a husband and children of my own and I could not imagine where a spare additional mother would fit into the family structure. Later still I realised that I didn’t want to learn that my mother had been felled by a fearsome hereditary disease that I was likely to develop, or that she was still alive and had some form of senile dementia that would leave me, despite her abrogation of me, somehow bound to take responsibility for her.

So for these semi-rational reasons, which no doubt hide a deeper, more profound anxiety, I have never tried to find my mother. I was (and still am) more interested in finding out who my father was, but that would be a much harder task since his name does not appear on my birth certificate. Maybe I will someday follow that path to discovery, if time is allowed to me, if only for my children and grandchildren’s sake. They have the right not to have a central branch of their already woefully sparse family tree amputated.

Chapter Three

An Education (of Sorts) (#ufc64f6c2-df03-58ee-bfa5-8d308ac349ac)

My first memory of my education is a Freudian one. I was standing next to a little boy on my first day at what was grandly called ‘nursery school’ but was a corner of the dining room in a neighbour’s house. There was a toy cash register, some Meccano, a doll’s pram accommodating a doll and a dog-eared teddy bear with a tea towel as a coverlet, and a sandpit in the garden, covered by a tarpaulin which was rolled back in the summer to allow ‘messy play’ with buckets and spades and child-sized watering cans. Perhaps there was a roll of blue sugar paper and wax crayons or poster paints to make pictures with, and blunt scissors and squares of coloured sticky paper too, but I don’t remember.

What I do remember was the willy this little boy fished out of his shorts and directed at the lavatory (or toilet as I was instructed to call it) as a stream of wee arced precisely where it was intended to go. I felt sheer, gut-wrenching penis envy – the functionality, the utility, a body part with the same straightforward application as a garden hose, no more lifting up skirts, pulling down knickers, balancing precariously on cold porcelain rims. I wanted what he had and carefully checked and rechecked my anatomy to see if somewhere I too had such a tap. I had no idea if this was a usual male adjunct, or if this particular child had been singularly blessed – or maybe adapted? And as far as I remember, I never asked, just coveted.

I One Potato, Two Potatoes . . .

The postwar government had other educational priorities so, largely for financial reasons but also in the belief that very young children were best at home with their mothers, it discouraged local authorities from investing in pre-school education when so many resources were needed for the provision of secondary schooling following the 1944 Education Act. Indeed, as late as the 1960s, the percentage of children attending nursery schools had barely increased since the 1930s, and where this was provided it was usually as a result of local authority subsidies for underprivileged areas. My nursery was a private one, paid for weekly, I imagine, with a charge that included a mid-morning beaker of milk and a biscuit. It would be pressure from married women wanting to go back to work in the 1960s and 70s that finally led the government to develop systematic pre-school provision for the children of any parent who wanted to make use of it.

Since I was an only child with no cohabiting playmates, I was fortunate to be able to spend time with a handful of other children of my age, learning to share, make friends, play with bricks, sing ‘Old MacDonald Had a Farm’ and ‘Ten Green Bottles’, and to write my name in higgledy-piggledy capitals.

After a year or so at nursery it was time to go to ‘proper school’, so I was sent to George Street primary, a former board school, just down the hill from where we lived. It was a grim place with high windows so children could not be distracted by what was going on outside. The lavatories were in the far corner of the yard. They were fitted with doors that didn’t close properly so you somehow had to stretch one leg from where you were sitting to keep the door shut while naughty boys tried to get in. There was an asphalt playground back and front with an inevitable tendency to graze knees, yet with no play equipment; games at playtime consisted of chalking hopscotch squares on the ground or playing fives with pebbles. The girls walked round and round the playground, arms intertwined, or skipped, tucking their dresses into their knickers and chanting ‘One potato, two potatoes, three potatoes, four’ as they jumped over the turning rope held by two friends.

As I grew older I considered the home counties a dull and unenviable place to grow up. It had no distinctive regional culture, traditions or dialect. It was neither urban nor rural, but a commuter land full of dormitory towns where people came home and tended their gardens or did a little light woodwork in their refuge shed after the train had dropped them off from London at about six o’clock. My father worked locally and so walked home for dinner (lunch) and then came home to high tea, which I remember as a meal of ham, hard-boiled eggs, lettuce and a lot of beetroot, though the repast must have varied sometimes.

You could plot the days of the week by the meals we ate: roast meat on Sunday, the remains of the joint on Monday, shepherd’s pie on Tuesday, with the last stringy remains of Sunday’s meal minced, macaroni cheese on Wednesday, liver and onions (ugh) on Thursday, fish on Friday. Puddings were things like plum pies, treacle tart, suet pudding and Bird’s Instant Whip, which my mother claimed was ‘home made’ as she added milk to the strawberry, banana or caramel packet powder.