По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

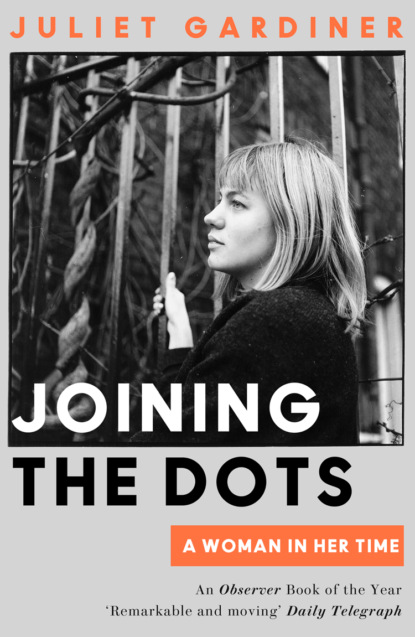

Joining the Dots: A Woman In Her Time

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Hemel Hempstead, where I grew up, was a smallish Hertfordshire market town and did not become suburbanised in the first wave of suburb-building. Mostly the town was not part of the 1930s growth of home ownership away from the crowded and fetid capital. No ring roads emanated from its core, though it was obviously ripe for change, given the postwar planning movement to settle families around the circumference of London and other overcrowded industrial towns and cities, but it would always lack any distinction as far as I was concerned.

This perception was confirmed when I read Iona and Peter Opie’s collection of the rhymes children chanted as they skipped, published in 1959 when my skipping days were not long past, and noted fascinating topical, regional and local references. In Lancashire the Opies heard girls chime, to the tune of ‘Red Sails in the Sunset’, a rhyme about a GP in Lancaster who had been hanged in 1936 for the murder of his wife and the girl who looked after the children:

Red stains on the carpet, red stains on your knife

Oh Dr Buck Ruxton, you murdered your wife,

The nursemaid she saw you, and threatened to tell,

Oh Dr Ruxton, you killed her as well,

as they skipped. In 1952 in Hackney, the Opies reported hearing children chanting in a primary school playground:

We are three spivs of Trafalgar Square,

Flogging nylons, tuppence a pair

All fully fashioned, all off the ration,

Sold in Trafalgar Square,

as they jumped. But for us it was: ‘One potato, two potatoes, three …’

George Street primary school served a socially mixed, though all-white, British-born population. It closely mimicked the social composition of the road where my parents and I lived, round the corner from the school. At the top of the hill lived a bank manager and his family (my mother always maintained that all bank employees, not just managers, were paid a handsome wage so that they would not be tempted to put their hands in the till), a doctor, a couple of solicitors, a vet and a local entrepreneur who made a comfortable living out of growing watercress, if judged by the car he drove and the holidays the family took. Our house, 33 Adeyfield Road (modified by my father, who was a local authority sanitary inspector with aspirations to train as an architect), was about halfway down the hill. Next door to us lived a shop manager and next door again was the owner of a sports shop which sold mainly golf clubs and tennis racquets. On the other side were fields.

Rows of crimson standard roses flanked the crazy-paving path to our front door, which sported a porthole window depicting a galleon in full sail in green and amber stained glass. The low brick wall separating the garden from the road was castellated, but its heavy chains had been requisitioned for war service and were never demobbed. This loss aggrieved my mother when she heard rumours that such chains had not been used to aid the war effort at all, but rather dumped in the North Sea since no one was sure what to do with them. The rest of the garden was enclosed by a rather scrubby hedge of laurel, which gave the house its name. The leaves were a source of some interest to me, since if I scratched my name on the reverse side of a leaf and shoved it up my jumper sleeve, the warmth would cause the writing to be clearly inscribed on the other side.

The bottom of the hill was distinctly working-class – ‘common’, or ‘rough’, as my mother called it. There was a field that was used for the twice-annual fair and circus, and where children played (I was forbidden to). There was a corner shop from which you could buy penny ice lollies, or in my case I was sent to buy a ‘family-sized’ brick of Wall’s Neapolitan ice cream – innocent of a single non-synthetic ingredient – wrapped in newspaper for ‘dessert’ on Sunday.

The children from the ‘nether regions’ included eight from an Irish family, the oldest of whom, Maureen, had plaits so long she could sit on them. Then there was Raymond, a pale, thin (‘weedy’) boy who always wore plimsolls and pink National Health spectacles mended with Elastoplast and whose nose continually ran. There was spiteful, mean-faced Yvonne, who used to torment me by recruiting her friends to bar my way home, and Clive, a red-headed adenoidal butcher’s son and something of a ten-year-old Lothario, keen to chase girls into the bushes for a bit of a fumble. These were my classmates: Susan, the watercress grower’s daughter; Sandra, whose father went up to ‘town’ on the train from Boxmoor station every morning with a briefcase, presumably to work in an office; Jennifer, whose father worked at the Dickinson paper mills – a substantial local employer in nearby Apsley, manufacturer of Basildon Bond writing paper (azure was the colour of choice in our house); Carol, whose father was a fireman and who lived above the shop, as it were; Michelle, a dentist’s daughter; and Patsy, whose mother worked in a smart dress shop in Watford and who wore gilt earrings, heady perfume and dark red nail-varnish. ‘Fast’, my mother – who made do with a puff of Coty powder, a splash of 4711 cologne and a dash of Miners coral lipstick – pronounced, though I thought her the height of glamorous sophistication and envied freckled Patsy.

The grown-ups at George Street school who made the greatest impression on me were the headmistress, stern Miss Parkin, with her iron-grey hair in tight curls clinging to her skull, and the voluptuously lovely and kind teacher, Miss East, who had blonde hair and pink cheeks and who praised me excessively when, aged five, I demonstrated that I could spell yellow – a skill that has never left me.

The classrooms were hardly hives of creativity. The notion that the pictures children painted themselves should adorn the walls had not been considered, so we spent our days gazing at Ministry of Education-issue colour prints of farmyards, a seaside harbour, a train station or an airport. We chanted what we could identify – tractor, pigsty, suitcase, trawler – and then wrote the words down with laborious pot-hooks using a wooden-handled pen with a nib which we dipped in ink. We did ‘gym’ in the playground a couple of times a week when it wasn’t raining. The only other diversion I recall was ‘nature study’, when a large wireless was carried into the classroom by the only male teacher in the school, so we could listen to a BBC educational broadcast. Mr Robertson sat by his teaching aid throughout the lesson like a security guard, flexing a ruler, ready to rap a knuckle sharply if, say, a boy was to giggle, pinch his neighbour, flick paper pellets or pull the plaits of the girl sitting at the desk in front.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: