По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

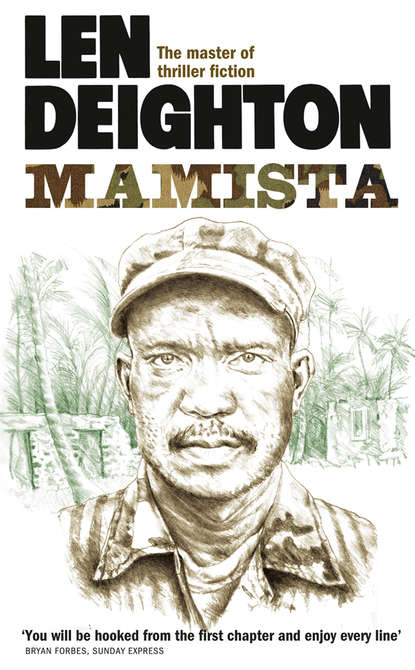

MAMista

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You can’t believe all that BBC propaganda,’ said the investments man. ‘That TV programme was a repeat. If my memory serves me, it was originally shown back in the Eighties before the Wall came down.’

The chairman watched them but said nothing.

What a circus! If it was always like this, thought Lucas, it would be worth the journey up to town every month.

‘Gentlemen,’ said the lawyer in a tone he normally reserved for consulting counsel. ‘While I wouldn’t agree with Colonel Lucas that this is entirely a medical question, I believe we are all beginning to see that we need more medical information before we can make a decision. After all’ – he looked at them and smiled archly before reminding them how important they were – ‘we are dealing with a great deal of money.’

Clever the way he can do that, thought Lucas. They were clucking away happily now, like a lot of contented hens.

‘What’s the form then?’ said the man from Birmingham in an effort to move things along.

‘An on-the-spot report,’ said the lawyer. He had the infinite patience that the law’s bounty and unhurried pace provide. He gave no sign that this was the fourth time he’d said it.

‘In any case, we all agreed that the antibiotics should be sent,’ said the investments man, although no one had agreed to it, and someone had specifically advised against that course of action. ‘Let’s send that immediately, shall we?’

The lawyer did not respond to the suggestion, knowing that putting it to the vote would start new arguments. Thankful that the dispute about the anonymous donor now seemed to have faded, he picked up a pile of paper and tapped it on the table to align the edges. He did it to attract their attention: it was a trick he’d learned from his partner. As they looked round he said, ‘Getting someone to Guiana and back shouldn’t delay us more than a week or two. Then, if we decide to go ahead, we can airfreight the urgent supplies.’

‘If we decide to go ahead,’ said the peer. The lawyer smiled and nodded.

The secretary said, ‘I think I might be able to arrange the air freight at cost or even free through one of our benefactors.’

‘Excellent,’ said the research man.

Bloody fool, thought Lucas, but he modified the thought: ‘Much better to buy locally whenever possible. Cash transfer. Ship it from Florida perhaps.’

The lawyer gave an audible exhalation. ‘We must be careful. Graft is second nature in these countries.’

‘Easier to protect money than stop pilfering of drugs and medicines,’ said Lucas. ‘In fact we should look at the idea of flying it right down to the southern provinces where it’s needed.’

‘And of course there will be customs and duty and tariffs,’ said the lawyer. It would be a nightmare and he was determined to dump it into someone else’s lap if he could.

‘That should be arranged in advance,’ said Lucas. ‘World Health Organization people must put the pressure on the central government. It would be absurd to pay duty on medical supplies that are a gift to their own people.’

‘Well, that will be your problem,’ said the lawyer.

Lucas looked at him and eventually nodded.

The chairman picked up the agenda and said, ‘Item four …’

‘Hold on. I don’t understand exactly what we have decided,’ said the investments man.

The lawyer said, ‘Colonel Lucas will fly out to Spanish Guiana to decide what medical aid should be given to people in the southern provinces.’

‘The Marxist guerrillas,’ said the man from Birmingham.

‘The people in the southern provinces,’ repeated the chairman firmly. He didn’t say much but he knew what he wanted the minutes to record.

The lawyer said, ‘The donor has offered to arrange for a guide, interpreter and all expenses.’

They looked at Lucas and it amused him to see in their faces how pleased they were to be rid of him. It was not true to say that Lucas nodded without thinking about it. He had no great desire to visit Spanish Guiana, but the medical implications of a large organized community living isolated deep in the jungle could be far-reaching. There was no telling what he might learn: and Lucas loved to learn. More immediately; he was the medical adviser to the board. They’d expect him to go. It would give him a change of scenery and he had no family responsibilities to consider. And there was the unarguable fact that he could report on the situation better than any man round this table. In fact better than any man they could get hold of at short notice.

Lucas nodded.

‘Bravo, Colonel,’ said the man from Birmingham.

The peer smiled. The jungle was the best place for the little Australian peasant.

‘Item four then,’ said the chairman. ‘This is the grant for the inoculation scheme in Zambia. We now have the estimates for the serum …’

Lucas remembered that he was supposed to meet his daughter next week. Perhaps his sister would meet her instead. He’d drop in on her as soon as this meeting ended. She’d question him about his trip to South America and then claim to have divined it in the stars. Oh well. Perhaps it would have been better if she had got married, but she’d chosen instead to look after his ailing parents. He felt guilty about that. He’d never given any of the family anything to compare with the love and devotion they had given him. Too late now: he’d take his guilt to the grave.

He’d tell her what he knew himself and that wasn’t much. He looked down at the pad in front of him. He’d drawn a jungle of prehensile trees, each leaf an open hand. On second thoughts he’d tell her little or nothing. He’d only be away three weeks, a month at the most.

Serena Lucas, his unmarried sister, lived in a smart little house in Marylebone. Ralph could never enter it without feeling self-conscious. The polished brass plate on the railings was as discreet as any lawyer’s shingle. Only the symbol beneath her name told the initiated that here lived a clairvoyant.

A disembodied voice came in response to the bellpush. ‘It’s Ralph,’ he said into the microphone. A buzzer sounded and he opened the door.

The short narrow hall immediately gave on to a staircase. These houses were damned small: he would not like to live in one. But it was immaculately kept. The carpeting and the furnishings were good quality and carefully chosen. On the wall he saw a new lithograph: a seascape by a fashionable artist. He guessed it had been payment for some shrewd piece of advice. She encouraged her clients to give her such gifts and usually got generously overpaid. The old witch was clever, there was no doubt about that, whatever one thought about the supernatural.

‘That’s a fine print,’ said Ralph as his sister came out of her study to greet him.

They kissed as they always did. She offered each cheek in turn and he avoided disturbing her make-up. Madame Serena was an attractive woman four years younger than Ralph. She was slim and dark with a pale complexion and wonderful luminous eyes that were both penetrating and sympathetic. Perhaps such colouring fulfilled her clients’ expectations of Bohemian blood, but the tailored suit, gold earrings and expensive shoes were another dimension of her personality. The fringed handbag with its beadwork was the only hint of the Gypsy.

‘What a lovely surprise to see you, Ralph.’ She pronounced it ‘Rafe’ as one of her well-bred clients had once done. Her voice had no trace of the Queensland twang.

‘I was passing. I hope you’re not too busy.’

‘The day before yesterday I had a senior Cabinet minister here,’ she said. She had to tell him the moment he got inside the door. She was still the little sister wanting his approval and admiration.

‘Not the Home Secretary trying to find a way out of that hospital scandal?’

She didn’t acknowledge his joke. ‘Ralph. You know I never gossip about clients.’ And yet in her manner she was able to imply that she had been consulted on some vital matter of government policy.

‘I’m sent to South America, Serena. Just a week or so. I wonder if you would meet Jennifer next Wednesday afternoon? If not, I will see if I can contact her and change the arrangements.’

She did not reply immediately. She led him into the drawing-room and they both sat down. ‘Would you like tea, Ralph?’

‘Have you caught this appalling English habit of drinking tea all day?’

‘Clients expect it.’

‘And you read the tea-leaves.’

‘You know perfectly well that I do not. Tea relaxes them. The English become far more human when they have a hot cup of tea in their hand.’

‘Do they? I shall bear that in mind,’ said Ralph. ‘You’ll meet Jennifer then?’

His sister and daughter did not enjoy a warm relationship but he knew Serena would not refuse. They had grown up in a warm congenial family atmosphere where they did things for one another. She took a tiny notebook from her handbag and turned it to the appropriate page. ‘I have nothing I cannot rearrange. What time is the plane arriving?’