По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

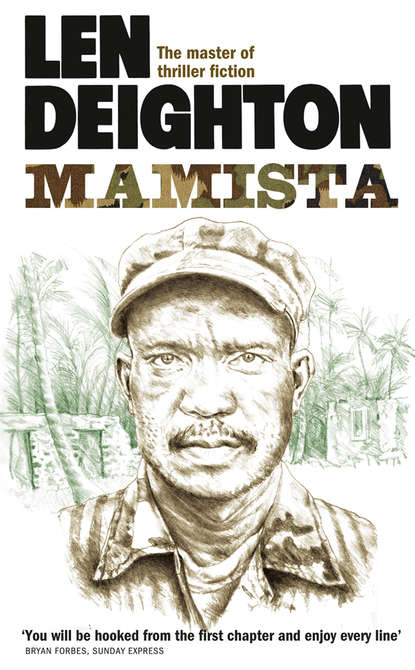

MAMista

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘With what purpose were the bombs set off?’ asked the interviewer.

The police colonel looked directly into the lens and said, ‘To destroy the microfilm records. To interrupt and delay payments to government workers and pension payments to retirees.’

‘Do the police have any leads?’

‘The police laboratory believe they have identified the explosives and the probable source of them. The Union of Government Servants has asked their members to cooperate fully against this new campaign of murder. Even the PEKINista high command has protested. In a statement this afternoon, they say they are opposed to the bombing campaign of the MAMistas.’

‘Can we expect arrests?’

Chori switched off the TV. The police colonel wobbled and expired. ‘You can see what they are trying to do,’ Chori told the world at large. ‘Trying to lever the Pekinista guerrillas apart from us. If you went to the hospital you’d find a couple of people with scratches.’

Paz nodded, but the chances that his explosion had blown the windows out, and injured someone in the street below, were not to be dismissed.

Chori picked up Lucas’ can of beer, shook it to be sure it was empty, then raised an enquiring eyebrow.

‘Yes, if you can spare it,’ said Lucas. He was being stuffy and British. He felt he should make an effort to be cordial.

Chori said, ‘The airport shakedown was just a stunt to push the bomb into second place on the news.’

‘I was there,’ said Lucas. ‘The police seemed to be concentrating upon the Indian families.’

‘That’s the joke,’ said Chori, handing Lucas his beer. ‘You saw them, did you? They are the cocaleros. Those Indian farmers are the people who are growing that shit. They take their crops to the jungle laboratories that are owned by Benz and his government cronies. What a joke.’

‘Are they rich?’ Lucas asked.

‘The cocaleros? No. You saw them. Poor bastards scrape together a few pesetas to have a cheap plane trip here to buy shoes twice a year. But they are making more than they’d make from growing coffee.’

Lucas got up and walked back to the window, as if a view across the rooftops would help him understand what was going on here. At the intersection he saw curious curved marks on the road. They were familiar and yet he couldn’t place them. It was only when he noticed that the cop on traffic duty had a machine gun over his shoulder that he recognized the marks as the damage done when a tank turns a corner. Tanks. Despite so many outward appearances of normalcy, this was a damned dangerous town.

‘It’s hot,’ said Angel Paz.

‘It will be hotter in the south,’ Chori said.

So the young man was going south too. ‘And cold nights until the rains begin,’ Lucas added.

The foreigners looked at each other as they realized that both of them would be going to the MAMista permanent base. No newspaper people were ever allowed there and those who’d gone without permission had not returned to tell the story. Angel Paz said, ‘How long will you be there?’

‘I am not political,’ Lucas said. He wanted to get that straight before they shared any of their wretched secrets with him. ‘Strictly business. I am doing a health check. In and out: a week or ten days.’

Paz said, ‘Uncommitted. In this part of the world the uncommitted get caught in the cross-fire.’

‘You should get your hair cut before we leave,’ Lucas said. ‘Right, Chori?’

‘You’ll be running with lice otherwise,’ said Chori.

‘We’ll see,’ said Angel Paz, running a hand back through his wavy locks. His hair had taken a long time to grow this long, and it looked good this way.

Lucas was getting hungry and there was no sign that food would be coming. ‘Can I buy you a meal?’ he said.

Chori said, ‘There is a party at The Daily American. There will be plenty to eat and drink.’

‘What is it?’ asked Lucas.

Chori said, ‘A Yankee newspaper. In English. They invite liberals and left-wingers for hamburgers and wine. You know the kind of thing. There will be plenty of everything. If you are still hungry, the San Giorgio across the street does a decent plate of spaghetti.’

‘That will do,’ said Lucas.

Chori said, ‘You are both sleeping here tonight. Make sure you know the address. I’ll have to be back before curfew but your foreign passports will get you past the patrols. And for God’s sake don’t run away from them.’

The office of The Daily American had that comforting sign of over-capitalization that is the hallmark of all American enterprises from fast-food counters to orthodontists. It was on the fifth floor of one of the few buildings in Tepilo built to withstand earthquake tremors and incorporating such safety equipment as sprinklers. When he got out of the elevator Lucas was greeted by the distant sounds of recorded music and noisy chatter.

He went down a corridor to a large reception hall that had comfortable sofas and a glass-topped desk with an elaborate telephone system. It was this area, and the room where the morning conference was held, that was made available for the party. The doors to the offices with the desks, word processors and other equipment, were locked. A hi-fi played Latin American music: cumbia, salsa and the occasional samba.

The fluorescent lights had been replaced by paper lanterns and the rooms were decorated with palm fronds and artfully folded pieces of aluminium kitchen foil. The air-conditioning was fully on. The guests were noisy and jovial, and in that slightly hysterical state that free food and drink brings.

Upon the conference table were paper plates and plastic knives and forks. Platters of sliced sausage, square slices of processed cheese and slices of rectangular ham were decorated with olives and sprigs of herb. Also upon the long table were electric hotplates with frankfurters and chilli. There was American coffee too and, on a bench under the window, Chilean white wine stood in buckets of ice.

In keeping with the liberal persuasion of the newspaper proprietor, there were no servants. Lucas accepted a glass of cold wine and briefly conversed with a man who wanted to display his familiarity with London. He talked with a couple of other guests before catching sight of Inez. He picked up a bottle of wine and took a clean glass. He’d poured two glasses of wine as he felt a tap on his shoulder. ‘Inez,’ he said. He had been about to use the wine in order to interrupt the conversation he’d seen her having with a handsome man in unmistakably American clothes.

‘You have been here for ages, and did not come across to speak,’ she said. It was such a coy opening that she could hardly believe that she was using it.

He gave her a glass of wine and looked at her. She was wearing a simple black dress with a gold brooch. A patent-leather purse hung on a chain over her shoulder.

She sipped and, for a moment, they stood in silence. Then she said, ‘You were deep in conversation?’

‘Yes,’ Lucas said. ‘An American from the embassy. He used to live in London.’

‘O’Brien. Mike O’Brien.’

‘Yes, that’s right,’ Lucas said.

‘CIA station head for Spanish Guiana, and maybe all the Guianas.’

‘You don’t mean it?’

She smiled.

He turned so that they could both see the mêlée. ‘Well, he seemed a decent enough chap. You think he was sounding me out?’ When she didn’t answer he said, ‘Well, yes, you’re right. We should assume that he heard someone like me was coming.’

As if aware that they were talking about him, Mike O’Brien smiled at Inez from across the room.

‘He knows you,’ said Lucas.

‘My name is Cassidy. It goes back many generations here in Guiana. My great-grandfather Cassidy was the first judge. But O’Brien likes to joke that we are both Irish.’

‘Does he know …?’

She turned to him. ‘It’s difficult for a foreigner to understand but many of the people in this room know that I am one of the people who handle statements for the MAMista command.’