По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

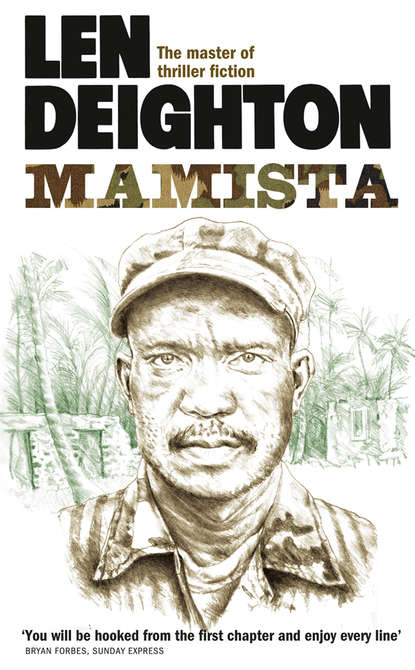

MAMista

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘London–Heathrow at five.’

‘Wednesday is not an auspicious day for travelling, Ralph,’ she said.

‘Perhaps not, but we can’t consult you every time anyone wants to go somewhere.’

She sighed.

Ralph said, ‘I wish Jennifer had chosen a college somewhere in the south.’

‘You fuss over her too much, Ralph. She is nineteen. Some women have a family and a job too at that age.’ Serena took a small antique silver case from her handbag and produced a cigarette. She lit it with a series of rapid movements and breathed out the smoke with a sigh of exasperation. ‘You should think of yourself more. You are still young. You should meet people and think about getting married again. Instead you bury yourself in that wretched house in the country and finance every whim your daughter thinks up.’ She extended a hand above her head and flapped it in a curious gesture. Ralph decided that it was an attempt to wave away the smoke.

‘That’s not true, Serena. She never asks for extra money. If I bury myself in the country it’s because I’m in the workshop finishing the portable high-voltage electrophoresis machine. It could save a lot of lives eventually.’ He smiled. ‘And I thought you liked my house.’

‘I do, Ralph.’ He’d discovered the ramshackle clapboard cottage on the Suffolk coast, and purchased it against the advice of everyone, from his sister to his bank manager. It was now a welcoming and attractive home. Ralph had done most of the building work with his own hands.

Sitting here with his sister – so far from the home in which they’d grown up – Ralph Lucas wondered at the way both of them had changed. They had both become English. His sister had embraced the English ways enthusiastically, but for Ralph Lucas change had come slowly. Yet even his resistance and objections to English things had been in the manner that the English themselves rebelled. Nowadays he found himself saying ‘old boy’ and ‘old chap’ and wearing the clothes and doing all kinds of things done by the sort of upper-class English twit he’d once despised. England did this to its admirers and to its enemies.

‘South America,’ said Ralph to break the silence.

‘I knew you’d be crossing the water, Ralph,’ she said.

‘Do you make it three weeks or a month?’ he asked with raised eyebrow.

‘Oh, I know you’ve never believed in me.’

‘Now that’s not true, Serena. I admit you’ve surprised me more than once.’

Encouraged she added, ‘And you will meet someone …’

‘A certain someone? Miss Right?’ He chuckled. She never gave up on arranging a wife for him: a semi-retired tennis champion from California, an Australian stockbroker and a widow with a flashy country club that needed a manager. Her ideas never worked out.

She leaned forward and took his hand. She’d never done anything like that before. For a moment he thought she was going to read his palm but she just held his hand as a lover – or a loving sister – might. He recognized this as a sign of one of her premonitions.

‘Chin up! I’m only teasing, old girl. Don’t be upset. I didn’t mean anything by it.’

‘You must take care of yourself, Ralph. You are all I have.’

He didn’t quite know how to respond to her in this kind of mood. ‘Now! Now! Remember when I came back from Vietnam? Remember admitting the countless times you had seen a vision of me lying dead in the jungle, a gun in my hand and a comrade at my side?’

She nodded but continued to stare down at their clasped hands for a long time, as if imprinting something on to her memory. Then she looked up and smiled at him. It was better to say no more.

4

TEPILO, SPANISH GUIANA. ‘A Yankee newspaper.’

Ralph Lucas did not much like flying and he detested airlines and everything connected with them. He dreaded the plastic smiles and reheated food, their ghastly blurred movies, their condescending manner and second-rate service. He had not enjoyed his ‘first-class’ transatlantic flight from London to Caracas via New York. Waiting at Caracas, he was not pleased to hear that the connecting flight to Tepilo was going to be even more uncomfortable. After a long delay he flew onwards in a ten-seater Fokker which had República Internacional painted shakily on the side. He shared the passenger compartment with six old men in deep mourning and six huge wreaths.

The flight was long and tedious. He looked down at the fever-racked coastal plain and the shark-infested ocean and remembered the joke about President de Gaulle choosing France’s missile launching site in nearby French Guiana. It was not sited there because at the Equator the spinning earth would provide extra thrust, but because ‘If you are a missile there, you’d go anywhere.’

Neither the runway nor the electronics at Tepilo airport were suited to big jets. A Boeing 707 with a bold pilot could get in on a clear day; and out provided it was judiciously loaded for take-off. Such an aviator had brought in an ancient Portuguese 707 that Lucas saw unloading cases of champagne and brandy into the bonded warehouse as he landed. There were other planes there: some privately owned Moranes, Cessnas and a beautifully painted Learjet Longhorn 55 that was owned by the American ambassador. There was a hut with ‘Aereo-Club’ on its tin roof so that visiting pilots would see it. Now alas, windows broken, it was strangled under weeds.

The main airport building – like the sole remaining steel-framed hangar – provided nostalgic recognition to passengers who had encountered the US Army Air Forces in World War Two. Little changed, these were the temporary buildings that the Americans had erected here, alongside this same runway, and the subterranean fuel store. Tepilo (or Clarence Johnson field as it was then named) was built as an emergency landing field for bombers being ferried to Europe by the southern route.

Upon emerging from immigration, Lucas looked round. The mourners with whom he’d travelled were being greeted by a dozen equally doleful men clutching orchids. All of them were dressed in three-piece black suits and shiny boots. Stoically enduring the stifling heat was an aspect of their tribute. All the airport benches – and the floor around them – were occupied by families of Indians in carefully laundered shirts and pants, and colourful cotton dresses. Their wide-eyed faces, and their hands, revealed that they were agricultural workers on a rare visit to the big city. Most of them were guarding their shopping: some pairs of shoes, a tyre, a doll and, for one excited little boy, a battery-powered toy bulldozer.

‘Mr Lucas?’

‘Yes, that’s me.’

She smiled at his obvious discomposure. ‘My name is Inez Cassidy. I am directed to take care of you.’

Lucas couldn’t conceal his surprise. It wasn’t just that the MAMista contact proved to be female that disconcerted him, it was that she was not at all the type he expected. She was slim and dark, her complexion set off by the shade of her brown shirt-style dress, whose simplicity belied its price. She wore pearls at her throat, a gold wristwatch and Paris shoes. Her make-up was slight and subtle. Anywhere in the world she would have attracted looks of admiration; here in this squalid backwater she was nothing short of radiant.

Her face was not only calm but impassive, held so to counter the insolent stares and whispered provocations that women endure in public places in Latin America. She touched her hair. That it was a nervous mannerism did not escape Lucas, and he saw in her eyes a fleeting glimpse of the vulnerability that she took such pains to conceal.

‘Will I fly south directly?’ Lucas asked, hoping that the answer would be no. He too was something of a surprise, wearing an old Madras cotton jacket, its pattern faded to pastel shades, and lightweight trousers that had become very wrinkled from his journey. He had a brimmed hat made from striped cotton; the sort of hat that could be rolled up and stuffed into a pocket. His shoes were expensive thin-soled leather moccasins. She wondered if he intended wearing this very unsuitable footwear in the south. It suddenly struck her that such a middle-aged visitor from Europe would have to be cosseted if they were to get him home in one piece.

‘May I see your papers?’ She took them from him and passed his baggage tags to a porter who had been standing waiting for them. She also gave him some money and told him to collect the bags and meet them at the door. The porter moved off. Then she read the written instructions and the vague ‘to whom it may concern’ letter of introduction that the Foundation had given him in London. It made no mention of Marxist guerrilla movements. ‘Tomorrow or Thursday,’ she said. ‘Sometimes there are problems.’

‘I understand.’

She smiled sadly to tell him that he did not understand: no foreigner could. She had met such people before. They liked to call themselves liberals because they sympathized with the armed struggle and tossed a few tax-deductible dollars into some charity front. Then they came here to see what was happening to their money. Even the best-intentioned ones could never be trusted. It was not always their fault. They came from another world, one that was comfortable and logical. More importantly they knew they would return to it.

She read the letter again and then passed it back to him. ‘I have a car for you. The driver is not one of our people. Be careful what you say to him. The cab drivers are all police informers, or they do not keep their licences. You have a British passport?’

‘Australian.’ She looked at him. ‘It’s an island in the Pacific.’

‘I have arranged accommodation in town,’ she said. ‘Nothing luxurious.’

‘I’m sure it will be just fine.’ Lucas smiled at her. For the first time she looked at him with something approaching personal interest. He was not tall, only a few inches taller than her, but the build of his chest and shoulders indicated considerable strength. His face was weather-beaten, his eyes bright blue and his expression quizzical.

She reached for his arm and pulled him close to her. If he was surprised at this sudden intimacy he gave no sign of it. ‘Look over my shoulder,’ she said softly.

He immediately understood what was expected of him. ‘A horde of policemen coming through a door marked “Parking”,’ he told her. He could see the porter, waiting at the exit holding his bags. Beyond him, through the open doors, police vans were being parked. Their back doors were open and he could see their bench seats and barred windows.

Head bent close to his she said, ‘Probably a bomb scare. They’ll check the papers of everyone as they leave the ticket hall.’

‘Will you be all right?’

Keeping her head bowed so as not to expose her face she said, ‘There is no danger but it is better that they do not see us together.’

Policemen passed them leading two sniffer dogs. She lifted Lucas’ hand and kissed it. Then, as she turned her body, he put his arm round her waist to keep up the pretence of intimacy. ‘I will be all right,’ she said. ‘I have a Venezuelan passport. Walk me away from the policemen at the enquiry desk: they will recognize me.’

In that affectionate manner that is a part of saying farewell, Lucas walked holding her close, with her head lolling on his shoulder. They went to the news-stand, his arm still holding her resolutely. When they stopped she turned to him and looked into his eyes.

‘You must remember the address. Don’t write it down.’ She glanced across to where two policemen had taken control of the enquiry desk. Then she made sure that the porter was still waiting with Lucas’ bag. She leaned even closer and said, ‘Fifty-eight, Callejón del Mercado. Ask the driver for the President Ramírez statue. He’ll think you are going to the silver market.’

As they stood together, half embracing and with her lips brushing his chin, he felt a demented desire to say ‘I love you’ – it seemed an appropriately heady reaction. There were police at every door now. They had cleared the far side of the concourse. Two policemen with pass keys were systematically opening the baggage lockers one by one. The one and only departure desk had been closed down and a police team, led by a white-shirted civilian, was questioning a line of ticket-holders. Some had been handcuffed and taken out to the vans.