По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

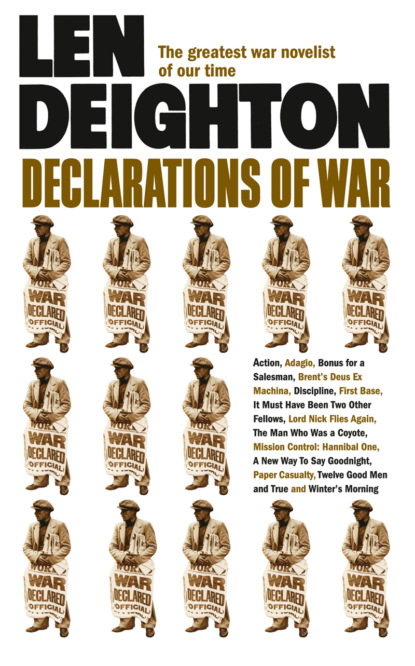

Declarations of War

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Wool twisted round in his seat and found a packet of cheroots in his jacket. He tore off its cellophane wrapping and opened it with a flourish. ‘Have a cigar?’

‘Thank you, Wool, no. I’ve given up smoking.’

‘It’s a rich man’s hobby now,’ agreed Wool. He put the cheroots away and took from the glove compartment a Havana in a metal container. He used a cigar-cutter to prepare it, and lit it with enough ceremony to demonstrate that he was a man familiar with good living. He exhaled the smoke slowly and turned to face the ex-Colonel with a calm happiness.

The Colonel had aged well; no surplus fat or heavy jowls. His nose was bony and his jaw was hard. He was lean and tall, just as Wool remembered him, except that the hair below his oily hat was almost white. Wool looked at Pelling’s hands. His dirty skin was tanned and leathery, just as one would expect of a man who spent long hours out in all weathers slaving at the petrol pumps.

Wool, on the other hand, was not so easy to identify with the nineteen-year-old Corporal that the Colonel had briefly known. Florid, and wearing large fashionable black-framed spectacles, he was like any one of the dozens of commercials who filled up at the Hillside before the non-stop race back to London. On his finger there was a signet ring and on his wrist a complex watch and a gold identity bracelet.

It must have been two other fellows, thought Pelling. Yes, as soldiers they had been saints or hooligans, torturers or rescuers, but none survived. Those that eventually became civilians were different men.

Pelling looked at the interior of the car. No doubt about it being cherished and cared for, even if it wasn’t done to Pelling’s taste. The steering-wheel had a leather cover, the seats were covered in imitation leopard-skin and a baby’s shoe dangled from the mirror. There was a St Christopher bolted to the dashboard and in the rear window there was a large plastic dog that nodded and two cushions with the registration number boldly knitted into their design.

‘Seen any of your blokes?’ asked Wool.

‘Not recently,’ said Pelling.

‘I’ve never been to an Old Comrades or anything.’

‘Nor have I,’ said Pelling. ‘I’m not much use at that sort of thing.’

Wool looked at the filthy raincoat. ‘I understand,’ he said. He studied the ash of his cigar. ‘The funny thing was that you only came up to the farmhouse for a look-see, didn’t you?’

‘I’m only here for a shufti, Lieutenant.’ The subaltern looked at the man crawling in through the door. The newcomer’s rank badges were unmistakable, and yet he looked younger than the thirty-year-old Lieutenant. ‘You came on foot, sir?’

‘Jeeped up the wadi.’

‘Corporal. Crawl out and move the Colonel’s Jeep into the barn out of sight.’

‘There’s eight gallons of water in it for you,’ said Pelling, ‘and a crate of beer for your chaps.’

‘That will cheer them up, sir.’

‘It won’t cheer them up much,’ said Pelling. ‘It’s that gnats’-pee from Tunis. Psychological warfare by the temperance people, I’d say.’

The Lieutenant rubbed his unshaven chin and nodded his thanks as the Corporal went out into the yard and started to move the Jeep.

‘It’s stupid of me,’ said Pelling. ‘I didn’t realize they could see as far as the track.’

‘They’ve got a new O.P. on the east slope of the big tit – Point 401 that is – we only noticed it yesterday, my sergeant saw a bit of movement there. Can’t be sure it’s manned all the time.’

‘It was stupid of me,’ repeated Pelling.

The Lieutenant had seldom spoken with colonels and certainly not one who’d admit to stupidity. Awkwardly he said, ‘Would you like to go up to the loft, sir? Sloan, get brewing. And open that tin of milk.’

The Colonel held the field glasses delicately, as though he was taking the pulse of two black-metal wrists. From the loft he could see more than ten miles along the valley. It was noon. The sunbaked hills were misty green puddings, surmounted by outcrops of grey rock and ringed by precarious terraces of crops. The olive groves lower down were plagued with the black festering sores of artillery fire, and untended vegetables had run to seed. Nowhere was there any movement of man or machine, nor were there horses or mules, cattle, sheep or goats – at least, no live ones. Pelling searched carefully along the German lines from where the River Caro was no more than a piddle of dirty water meandering through the high-banked wadi, to the ruins of ‘Sergeant-Major’, as the troops had renamed the village of Santa Maria Maggiore. If it hadn’t been for the cowshed at the far end of the yard, and the abandoned Churchill tank fifty yards behind it, he’d have been able to see the hills beyond the river, and the main road that led eventually to Rome. He studied the road carefully: dust hung above it like incense smoke, and yet he could see no transport there. From somewhere far away a church bell began tolling an inexpert rhythm.

‘A dedicated priest,’ said Pelling, still looking through the glasses. Then he lowered them and began to wipe the lenses. He used a white linen handkerchief, rough-dried and unpressed and mottled with the faint stains of ancient dirt.

‘Partisans, more likely. They use the bells as signals to regroup.’ He passed the Colonel a handkerchief of khaki silk. Bought by a loving mother for a newly commissioned son, thought Pelling as he finished polishing the binoculars. Handling the smelly glasses with exaggerated care, Pelling put them into the battered leather case and gave them back to the Lieutenant.

‘Your people will be coming tomorrow, sir?’

‘Yes, we’ll get rid of that tank and cowshed for you.’ He said it like a surgeon about to amputate, and like a humane surgeon he tried to give the impression that it would make things better.

‘That will give us quite a view,’ said the Lieutenant. Pelling nodded. They both knew that it would make the farm such a good observation point that then the Germans would also want it. Very badly.

‘Our attack can’t be far off now,’ said the Lieutenant, seeking reassurance. Pelling said nothing. Allied H.Q. didn’t tell engineer colonels their plans, any more than they told infantry subalterns. They told the one to clear fields of fire and the other to shoot.

Pelling said, ‘In another three or four weeks the autumn rains will make that valley into a bog. Do you know what rain does to that dusty soil?’ It was a rhetorical question; the Lieutenant’s face, hair, hands and uniform – like everyone else’s – were coloured grey by the same abrasive powder that got in the guns and the tea.

‘Yes,’ said the Lieutenant. The attack would be soon.

What sort of man would build a farm up here on the side of Monte Nuovo: a fool or an aesthete, or both. The wind screamed constantly, the cloud was almost close enough to touch and the trees were stunted and hunchbacked; but the view was like a Francesca painting. Back in Pelling’s part of the world men built their houses low.

In war, though, it was the villages in the valleys that survived best. Houses and churches on high ground were invariably destroyed as the armies fought for observation points. There was a moral there somewhere, thought Pelling, but he was too tired to deduce it.

‘What will you do after the war, Lieutenant?’ Pelling sipped the hot sweet tea that was heavy with the smell of condensed milk.

‘Oh, I don’t know.’ This was a new sort of conversation and he spoke in a different voice and omitted the ‘sir’. ‘I always wanted to be a vet – I’m keen on animals – but I’ll be too old to start studying by the time this lot’s over. Probably I’ll just take over the old man’s antique shop. And you?’

At first the Lieutenant was afraid that he’d offended the young Colonel. With an M.C. and D.S.O. and a colonel’s rank at his age, perhaps he felt that there was no other world but the army. To soften it a little the Lieutenant said, ‘You’re a regular, of course.’

Pelling grinned, ‘Yes. Woolwich, Staff College, the lot. I’m about as regular as you can get.’

‘I suppose this is…to us it’s the worst sort of interruption to our lives, but I suppose for you it’s the thing you’ve been waiting for.’

‘All you War Service types think that,’ said Pelling, ‘but if you think that any regular soldier likes fighting wars, you’re quite wrong.’ He saw the Lieutenant glance at his badges. ‘Oh, we get promotion, but only at the expense of having our nice little club invaded by a lot of amateurs who don’t want to be there. The peacetime army is quite a different show. A chap doesn’t go into that in the hope that there will eventually be a war.’

‘No, I suppose not.’

‘You won’t believe it,’ said Pelling, ‘but peacetime soldiering can be good fun, especially for a youngster straight from school. The army’s so small that one gets to know everyone. One travels a lot, and there’s ample leave as well as polo, cricket and rugger. It’s not at all bad, Lieutenant, believe me. Even the parade ground can have a curious satisfaction.’

‘The parade ground?’

‘A thousand men, perfectly still and silent…and able to move in precise unison. Professional dancers probably share the same elation.’

‘Like marching behind a military band? We did that once, passing out of OCTU.’

‘That’s a part of it, but for me a silent parade ground has even more of a ritualistic effect. The body moves and yet the mind remains. There is a separation of physical and spiritual self that can liberate the mind like nothing else I know.’

‘Are you a Buddhist, sir?’ It was a reckless guess.

‘Once I nearly was,’ admitted Pelling.

‘And now?’

‘I am slowly rediscovering Christianity.’