По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

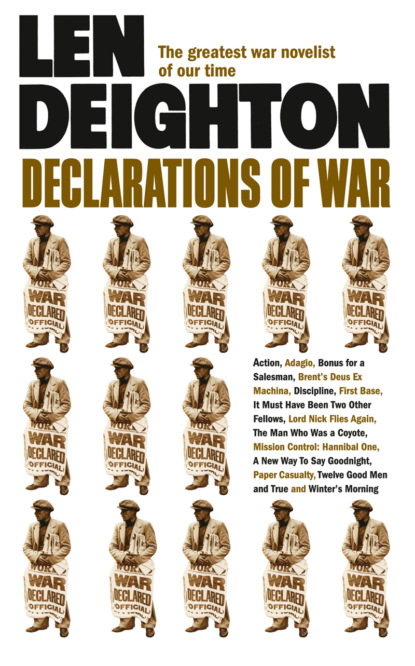

Declarations of War

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Very likely,’ said Pelling.

‘After all, you were just pointing at maps and giving orders. We were the people who actually did the work.’

‘That’s true.’

‘It is true, isn’t it? See, and in peacetime your good wages goes to chaps who do the real work.’ He heaved himself round in his seat and from a large carton in the rear seat he brought a Munchy bar and unwrapped it.

‘Like us?’ supplied Pelling.

Failing to find irony in Pelling’s impassive face, Wool broke the Munchy into four large pieces and offered the open wrapper to Pelling, who declined. Pelling knew that there would be cold meat and pickles waiting on the sideboard. Vaguely, he wondered what was on TV.

‘Ever go back to Italy?’ Wool asked.

‘Never,’ said Pelling.

‘Don’t like the Eyeties, eh? Yeah, I understand. I went back a couple of times. Package tour, very nice. Six cities in eighteen days. Just enough time to see the sights, not long enough to get bored. Course, I like the Eyetie food,’ he patted his stomach. ‘Perhaps it’s too oily for you, but I eat a lot of it: fettuccine alla panna, osso bucco, lasagne al forno. I’m quite an expert on the old cuisine Italiano. Mind you, you have to watch them with the women, they’ve got no respect for womanhood. My eldest was pestered by some waiter-type in Florence, but I didn’t have no nonsense. I reported him to the management and said I was a director of the firm that runs the tours – I’m not of course – and they sacked him.’

At least he went back, thought Pelling, he didn’t start four letters and finish none of them.

Pelling said, ‘So when you went out that night, you weren’t primarily trying to get the wounded fellow – Keats – back to the farmhouse?’

‘Your memory,’ said Wool. He chuckled. ‘It must be even worse than mine. No, the Lieutenant was right. That M.G. 42 had sliced old Keats up good and proper. The way I saw it, they probably had him in their sights, waiting for some medal-hungry twit to walk into them. I didn’t want to go near him.’

For the first time Pelling was clearly able to recall the young Corporal who had been with them that day and night. But everything about Wool had changed: his build, face, voice and demeanour. The Corporal had been a wiry fellow with a shy smile, a red face and a thin London accent. Wool finished his Munchy, burped, loosened his belt and reached for a jacket hanging behind him.

‘Look at this, Colonel.’ He delved into his wallet, pulling out paper money and various business cards and stuffing them back with tuts of irritation until he found what he was looking for: a photo. ‘That’s what I’ve done for myself. I may not have been an officer but that’s what I’ve done for myself.’

Pelling expected a photo of wife and family, but it was a photo of a house. Close behind it there were many others. ‘Nineteen thousand,’ said Wool. ‘Probably worth twenty-five by now. My old Gran left me her little house in the country. But it was a dead-and-alive little hole, so I sold it for nine hundred and had enough to put down on a bungalow in Morden. Do you know South London at all?’

‘No.’

‘It’s a very nice place where we live: doctors and that live there, well-to-do people. It’s so convenient to London, you see.’ While he was talking he’d sorted through his wallet and found another photo. He showed it to Pelling. Six young men, tanned and smiling, stood arms interlinked in the blazing African sun.

‘You were a different fellow then,’ said Pelling.

‘I was a little twit,’ said Wool bitterly, as though he hated the man that he saw in the photo. ‘Yes sir no sir three bags full sir. Creeping around, apologizing for being alive.’

‘That’s not how I remember you,’ said Pelling. ‘You were full of life, laughing and joking. And you were full of ideas too.’

‘Was I?’ said Wool. He could not remember the terrain or the tactical situation in the way that the thirty-year-old Pelling had remembered. Wool’s memories were simpler: the cold corned beef that he didn’t eat; Keats, the squint-eyed little Scottish private with the wrist-watch he’d taken from a dead German Grenadier; and the posh Lieutenant who pronounced Tedeschi so perfectly that Wool had imitated it ever since.

It made no difference which of them was assigned to guard duty, for they all sprawled on the floor near the windows. They ate their cold rations where they sat and passed their cigarettes from hand to hand, leaving their positions only to use the latrine pit twenty paces across the back yard.

‘That’s wealth, that farmland,’ said a private soldier named Stephens. He jerked his head towards the smashed window. Before the war he had been a solicitor’s clerk and was duly respected as educated.

‘D’ye not see these Italian farmers with the arse out of their trousers. Do you ken that, Stevie?’

‘Land is wealth,’ repeated Stephens, ‘but not necessarily a sound investment.’

‘Get on!’ said Private Teasdale. ‘Look at the price of a titchy little bottle of olives. About one and threepence, and how many in it? bleeding twenty!’

‘A dozen, more like,’ said Stephens, relieved to move the conversation away from the subject of land, of which he had only a tentative understanding. He stole a glance at the olive plantations on big tit. The hillside was studded with them and Stephens abandoned the task of calculating how many olives might be there.

‘What about gold?’ said Private Keats. ‘Bugger owning a farm! Too much like bloody hard work. What I’d want is a neat little gold mine. Dig up a couple of ounces every week. Just enough to pay the rent and give the old lady something to back her fancy at the dogs. That’s real wealth, gold is.’

‘Wealth is energy,’ said Stephens. ‘You know: power stations, hydroelectric stuff, plant and factories…even muscle power. Wealth is just energy.’

‘If you ask me,’ said Corporal Wool, speaking for the first time in several minutes, ‘wealth is time.’

‘What you mean, Corp?’ said Andrews. The new Corporal had that afternoon helped Andrews bring the water in from the Sapper Colonel’s Jeep without anyone asking him to. You didn’t get many corporals like that, in Andrews’s experience. This one should be cultivated. ‘Time is wealth, like?’

‘It’s the only thing you can’t buy, apart from good health,’ said Wool. ‘I mean, we think we’ve got the worst end of the stick, being up here at the sharp end being shot at, right?’ The others nodded. ‘But you think any of those old generals and that back at Div wouldn’t change places, no hesitation?’

‘Would they?’ said Keats. It was a thrilling concept. One to be toyed with. He hoped that it wouldn’t be exploded too soon.

‘Course they would,’ said Wool. ‘Here we are, fit and well and raring to go, with all our life in front of us. Course they would. Why, any of us could do anything…’

‘Well, not exactly anything,’ modified Stephens, who felt his position as the educated man might be jeopardized by this Corporal.

‘Anybloodything,’ said Wool. ‘Any of us could become generals or millionaires or bloody film bloody stars with the right gumption and a bit of luck.’

‘Get away,’ said Keats scornfully, but not so scornfully as to disturb the dream. Rather he said it to coax more details from the pink-faced Corporal. This fellow could do it, thought Keats. He might become a general or a millionaire or a film star. Or even a centre-forward for Celtic, which was Keats’s personal daydream.

‘I tell you,’ said Wool, ‘time is all you need. Twenty-odd years from now we could all be whatever we decide on.’

‘I’d like to be a centre-forward for Celtic,’ said Keats, believing that an early claim would have more chance of fruition.

Teasdale said, ‘I’d like to have a little grocer’s in Nottingham, near the tobacco factory. Lots of married women work there, they have to buy the food for the old man’s supper on the way home. In the side street for preference, and stay open late on pay night. And sell fags and sweets, too.’

Stephens said, ‘I’d have studied to be a solicitor, but I’m too old now.’

‘You’re not,’ said Wool, ‘honest, Stevie, you’re not too old. That’s what I’m telling you. It’s time that’s wealth. When this lot’s over you’ll have time to be a solicitor. You could end up a judge, even.’

‘And what about you, Corp?’ said Andrews.

‘Oh, me,’ said Wool. ‘I’m lucky in a way. I’ve got my future all waiting for me. My old Gran in the country has got five acres. I’ll get a cow and some pigs and chickens. I won’t make a fortune but I won’t be worrying my guts out trying to make a living either. You become a different sort of person in the country. Everyone does, it’s more natural somehow.’ It was then that Wool raised his eyes for a periodic glance at the horizon. ‘Two Ted Mark IVs turning off the track, near the road two o’clock.’

Wool’s voice alarmed Pelling, just as it had done at the time. ‘You were a cool customer,’ said Pelling. ‘I’ll tell you frankly, I was afraid when that shell hit the loft, but you climbed up there before any of us had recovered our wits. It was some silly joke you made that brought us all back to normal again. And then there was the tank…’

‘I was a twit,’ said Wool, pushing the memory of the loft and its smell of warm blood back into his dark subconscious. ‘Full of crap about esprit de corps, comradeship and loyalty. I’m not like that now, I’ll tell you.’

‘What are you like now?’ asked Pelling flatly.

‘I’m a go-getter. I look after number one and make sure that my expense sheets are countersigned and submitted bloody early. There’s no esprit de corps in the chocolate-bar business.’

‘I shouldn’t have let you go out to the tank,’ said Pelling.

‘How could you have stopped me? I knew it was my last chance before your bloody sappers arrived.’