По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

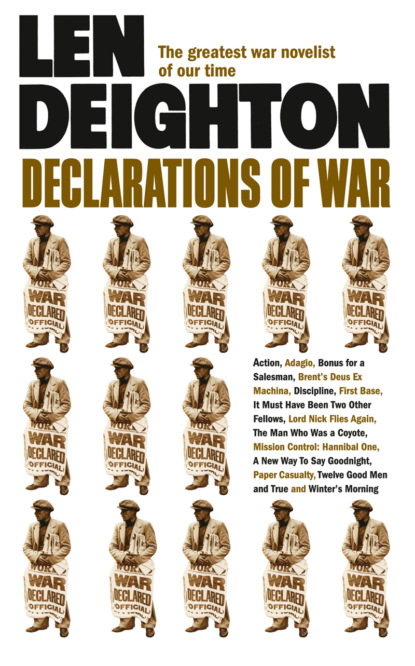

Declarations of War

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Pelling had told no one about the time he’d spent billeted in the monastery near Naples, of the long conversations he’d had with the Abbot, arguing so fiercely that at times they were both yelling. Apart from his driver no one knew of the trips to the slum villages, and not even the driver could have guessed the effect that time had had upon him. ‘I’m going into a monastery,’ said Pelling.

‘Really?’ He stared at the Colonel, trying to see some strange secret.

Pelling nodded. He did not doubt that he would go back to the great white building with its orchards and its library and the life that went on without interruption for century after century. It was arranged that he would get both the tractors going again and find or build a lorry that would take the produce into Naples where they would get a better price for their vegetables.

There had been times during the fighting when only the promise of a cloistered life kept Colonel James Pelling going. He visualized himself thirty years hence; stouter than Father Franco and quieter than Father Mario – and perhaps less devout than either. Yet, as the old man had explained, the Order had in the past received men with doubts, and some of these had become its most valuable sons. Would one ever get used to being called ‘Father James’, Pelling wondered.

‘Do you believe there is a heaven for tractors, Father James?’

‘If there isn’t, Brother, then Father James will not go there.’ They were truly good, those simple men.

‘Would you be able to stand that?’ It was the Lieutenant speaking. ‘The quiet: I’d go bonkers.’

‘It’s not a silent Order,’ said Pelling.

‘You’ve no family then?’

‘A father.’ He’d go – what was the word the Lieutenant had used? – bonkers. Yes, he’d go bonkers all right. But Pelling was determined not to repeat the mistakes of his father’s solitary life. Days in the boat yard or at the drawing-board, lunch in the pub with the works manager. Dinner in the yacht club, or a late snack left by cook: dry ham sandwiches clamped under a plate. And what was the purpose of his father’s life: a couple of knots gained by hull modifications, a win at Cowes, a telegram from a transatlantic cup winner. That wasn’t enough for him, not nearly enough. Pelling could hear the soldiers below talking about what they would do with their lives after the war.

‘Mr Steeple, sir.’ It was Wool’s voice calling softly, ‘Two Mark IVs turning off the road near the track at two o’clock.’

Lieutenant Steeple said, ‘Sergeant Manley, get your sniper’s rifle. Have a go at their visors. You never know, you might star his periscope glass.’

The Lieutenant was too late grabbing for the glasses. ‘They’ve stopped,’ grunted Pelling. He rubbed the lenses with a handkerchief and then looked again. ‘Nice hull-down position if they were going to batter us.’ Their guns hadn’t traversed, so it was difficult to know whether they were covering the main road or the farmhouse to the east of it. The Lieutenant picked pieces of straw from his duty battle-dress blouse while he waited for the next move.

‘You should wear denims,’ said Pelling without taking the glasses from his eyes. ‘That rough battle-dress material picks up straw and stuff.’ He couldn’t see very well, for the morning sun reflected on the dry, dusty soil so that it shimmered as he remembered the desert had done.

‘No, no, no, sir,’ interrupted Wool. He chuckled and flicked ash from his cigar. ‘It wasn’t hot and sunny, it was a close overcast day. There had been rain that morning. Not the sort of rain we got a few weeks later, but rain. And it wasn’t morning, it was late afternoon when the German tanks arrived, very late, almost dark. You were in the cellar drinking tea with that Mr Steeple, the officer. I came down the cellar steps and said, “Any more tea for anyone? There are a couple of Tedeschi tanks outside the front door.”’

‘Damn!’ shouted Steeple. Pelling looked around for a place to stand his mug of tea and then decided to drink it hurriedly. It scalded his mouth. Pelling let Steeple up the steps first. It was his show, but Pelling couldn’t resist interfering.

‘Radio?’ called Pelling.

‘Bishop!’ yelled Steeple. ‘Tell Company: Two Ted Mark IVs moving in on us fast.’ He looked at Pelling and said more calmly, ‘No, wait a minute, make that: Two Mark IVs, range nine hundred, bearing oh three five.’

Everyone stood very quietly listening to the radio operator patiently repeating the message. Only Pelling and Steeple could see the two enemy tanks. The others were just staring very hard at the wall and the rafters, as if by opening their eyes wide they would be able to hear better. It must have been three or four minutes before anyone spoke and then Wool said, ‘Listen to that nightingale sing! It’s as clear as a glass of Worthington…’

‘Couldn’t have been me,’ chuckled Wool. ‘I couldn’t tell a nightingale from a budgerigar; still can’t.’ He puffed his cigar. ‘What I do remember, though, is you making us black our faces with soot from the stove. Regular Sioux war party we looked.’

Wool had often played Red Indians when he stayed with his Gran. Blacking his face was an important part of that. He’d take his uncle’s boat and row along the stream. Using the oar against the river-bed, he could push himself right in among the reeds so that he and the boat disappeared. The cars on the road to Bishopsbridge were stage coaches, but pedestrians were miners and no honourable Indian brave would scalp them.

‘Did I?’ said Pelling.

‘Yes, it was after the rations came up that night. You nearly put Bishop on a charge when he said the soot would make no difference in the dark. You called him a young lout, I remember. He was a family man, too. He was real choked about that.’

‘None of them were louts,’ said Pelling. ‘They were good chaps.’

‘But that Keats was a dodgy one. He’d done three years for duffing up a policeman at a Cup Final in 1936. Sergeant Manley was a bit nervous of Keats. Never gave him any dirty jobs or anything dangerous.’

‘Was Keats the Scots lad that tried to get back along the ditch?’

‘That’s him; short thickset bloke with bad teeth.’

‘It was a brave thing to do.’

‘Brave?’ said Wool. ‘He was trying to give himself up to old Ted. He was off to surrender, thought he was going to get killed.’

‘You think so?’

Keats put his rifle to rest against the broken stove and then crouched by the window waiting for a break in the mortar fire. He went over the windowsill so skilfully that few men saw him go.

Like a burglar, reflected Pelling, yes, like a burglar.

‘Rifle grenades, not mortars,’ said Wool. ‘You taught me the different sound of those. Like a champagne cork popping, the two-inch mortar, you said. Mind you, I’d never heard a bottle of champers pop at that time.’ He laughed to remember his youth. ‘And it was a Sherman tank, not a Churchill.’

‘What makes you think that Keats was trying to surrender?’

‘He was carrying a piece of bed-sheet. It was tucked into the front of his blouse. When the burial party got up to him next day they thought he must be an old one – you know, swollen up with the sun – but it was a sheet.’

‘Poor fellow.’

‘Yes. Kept us going all night, didn’t he. Screaming and carrying on. Mona or Rhona or something. He was probably only nicked at first, if he’d kept quiet he would have been all right perhaps. Stephens tried to shoot him once, you know. It was too dark.’

Why had Wool chosen to remember it like that? Had the new fashion in embittered war films and stories persuaded Wool to distort the reality of his memory in favour of the more fashionable rubbish of writers who had not been there? Wool had been a hero: young, pimply, foolish and brave.

‘I’d like to have a go,’ said Wool.

‘It’s up to the Colonel,’ said Lieutenant Steeple. No one had to ask what Wool was volunteering for.

‘By all means,’ said Pelling. Already the valleys were dark, and the last glimmer of sunlight lit the church on the mountaincrest facing them.

‘I’ll go out the front,’ said Wool. ‘That’s where they’ll least expect me. I’ll make towards the Sherman in front of us and then work round to the track, keeping well away from the house. I’ll see if I can spot Keats, too.’

Lieutenant Steeple said, ‘Sergeant Manley, we’ll put some phosphorus grenades into the wadi end of the track. Make a rumpus while the Corporal gets clear.’ To Wool he added, ‘Keats is probably done for, don’t take any risks to bring him back.’

Pelling said, ‘Corporal, if you are spotted, lie low. We’ll tickle them up to give you a chance. If you need to come back to us, come in on a line with the barn. We’ll be extra careful on that bearing.’

The dark was like playing Red Indians, too. He’d crept up on the bison in Mr Jones’s field. Sometimes he’d be within touching distance before it ran away bleating. When he got out of the army he’d go back to Gran’s. He liked it in the country; Bell Street was a dirty place, without grass or trees or anywhere that kids could play. When he had kids they would have the countryside to play in. They’d row out into the reeds, as he had done, and catch fish and help old Mr Jones herd the Jerseys and carry the milk.

Hold it, there’s the tank right ahead. A Sherman Firefly with Cindy Four painted on it in red letters, that’s the one. It was just like being a Red Indian, except that the ground was cold and damp and the cowboys were using two-inch mortars and Mark IVs. His bloody knee! There was a stink of ancient dung and fresh human excreta, but the wet grass had a smell that he liked. Careful of the wire.

What sort of job could he get in the country? None that would bring much money, but then one didn’t need so much money in the country. Gran would let him have the room in the loft and there’d be agricultural training courses for ex-servicemen. He’d asked the Education Officer. Now that he knew Wool was serious he’d promised to get the papers about it from Division.

‘Did you ever think about one of those security organizations?’ said Wool. ‘Still, you’re not as fast on your pins as you used to be. They’d probably not want a bloke as old as you are. You might prove a bit of a liability up against a gang of toughs using ammonia and pickaxe handles.’

‘That’s true,’ said Pelling.

‘The trouble is,’ said Wool, ‘a colonel: what training has he got for civvy street? I mean, I was a driver. I remustered from infantry. I could find my way around an engine, too, at one time. Nowadays, of course, least little thing and she goes back into the garage. The firm pay all the repair bills. But coming out a sergeant with my mechanical skill made me a more desirable employee than you.’