По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

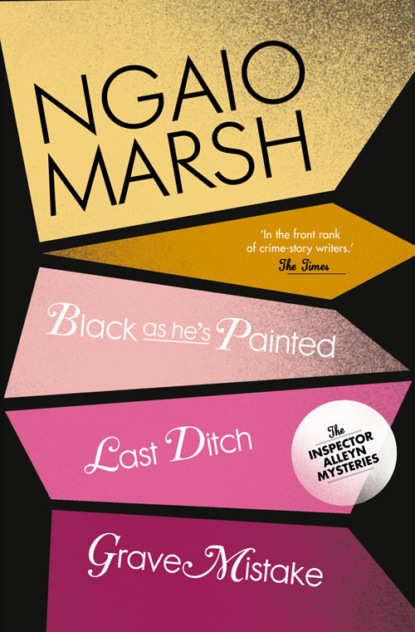

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘How did you know it was the waiter?’

‘I knew all right. I knew and no error.’

‘But how?’

‘Bare arm for one thing. And the smell: like salad oil or something. I knew.’

‘How long did this last?’

‘Long enough,’ said Chubb, fingering his neck. ‘Long enough for his mate to put in the spear, I reckon.’

‘Did he hold you until the lights went up?’

‘No, sir. Only while it was being done. So I couldn’t see it. The stabbing. I was doubled up. Me!’ Chubb reiterated with, if possible, an access of venom. ‘But I heard. The sound. You can’t miss it. And the fall.’

The sergeant cleared his throat.

Alleyn said: ‘This is enormously important, Chubb. I’m sure you realize that, don’t you? You’re saying that the Ng’ombwanan waiter attacked and restrained you while the guard speared the Ambassador.’

‘Sir.’

‘All right. Why, do you suppose? I mean, why you, in particular?’

‘I was nearest, sir, wasn’t I? I might of got in the way or done something quick, mightn’t I?’

‘Was the small, hard chair overturned during this attack?’

‘It might of been,’ Chubb said after a pause.

‘How old are you, Chubb?’

‘Me, sir? Fifty-two, sir.’

‘What did you do in World War II?’

‘Commando, sir.’

‘Ah!’ Alleyn said, quietly, ‘I see.’

‘They wouldn’t of sprung it across me in those days, sir.’

‘I’m sure they wouldn’t. One more thing. After the shot and before you were attacked and doubled up, you saw the Ambassador, did you, on his feet? Silhouetted against the screen?’

‘Sir.’

‘Did you recognize him?’

Chubb was silent.

‘Well – did you?’

‘I – can’t say I did. Not exactly.’

‘How do you mean – not exactly?’

‘It all happened so quick, didn’t it? I – I reckon I thought he was the other one. The President.’

‘Why?’

‘Well. Because. Well, because, you know, he was near where the President sat, like. He must of moved away from his own chair, sir, mustn’t he? And standing up like he was in command, as you might say. And the President had roared out something in their lingo, hadn’t he?’

‘So, you’d say, would you, Chubb, that the Ambassador was killed in mistake for the President?’

‘I couldn’t say that, sir, could I? Not for certain. But I’d say he might of been. He might easy of been.’

‘You didn’t see anybody attack the spearsman?’

‘Him! He couldn’t of been attacked, could he? I was the one that got clobbered, sir, wasn’t I? Not him: he did the big job, didn’t he?’

‘He maintains that he was given a chop and his spear was snatched out of his grasp by the man who attacked him. He says that he didn’t see who this man was. You may remember that when the lights came up and the Ambassador’s body was seen, the spearsman was crouched on the ground up near the back of the pavilion.’

Through this speech of Alleyn’s such animation as Chubb had displayed, deserted him. He reverted to his former manner, staring straight in front of him with such a wooden air that the ebb of colour from his face and its dark, uneven return, seemed to bear no relation to any emotional experience.

When he spoke it was to revert to his favourite observation.

‘I wouldn’t know about any of that,’ he said, ‘I never took any notice of that.’

‘Didn’t you? But you were quite close to the spearsman. You were standing by him. I happen to remember seeing you there.’

‘I was a bit shook up. After what the other one done to me.’

‘So it would seem. When the lights came on, was the waiter who attacked you, as you maintain, still there?’

‘Him? He’d scarpered.’

‘Have you seen him since then?’

Chubb said he hadn’t but added that he couldn’t tell one of the black bastards from another. The conventional mannerisms of the servant together with his careful grammar had almost disappeared. He sounded venomous. Alleyn then asked him why he hadn’t reported the attack on himself immediately to the police and Chubb became injured and exasperated. What chance had there been for that, he complained, with them all being shoved about into queues and drafted into groups and told to behave quiet and act cooperative and stay put and questions and statements would come later.

He began to sweat and put his hands behind his back. He said he didn’t feel too good. Alleyn told him that the sergeant would make a typescript of his statement and he would be asked to read and sign it if he found it correct.

‘In the meantime,’ he said, ‘we’ll let you go home to Mr Whipplestone.’

Chubb reverting to his earlier style said anxiously: ‘Beg pardon, sir, but I didn’t know you knew –’

‘I know Mr Whipplestone very well. He told me about you.’

‘Yes, sir. Will that be all, then, sir?’