По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

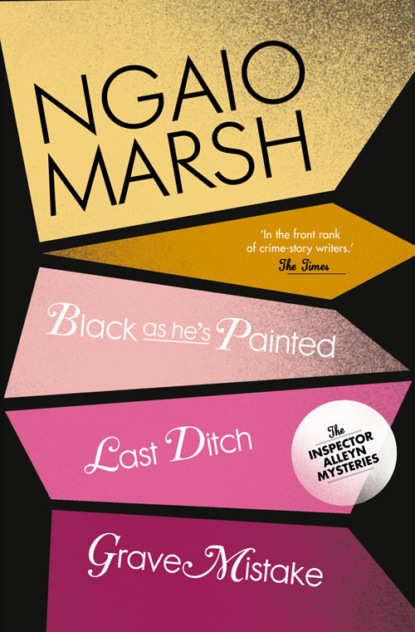

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I think so, for the present. Good night to you, Chubb.’

‘Thank you, sir. Good night, sir.’

He left the room with his hands clenched.

‘Commando, eh?’ said the sergeant to his notes.

II

Mr Fox was doing his competent best with the group of five persons who sat wearily about the apartment that had been used as a sort of bar-cum-smoking-room for male guests at the party. It smelt of stale smoke, the dregs of alcohol, heavy upholstery and, persistently, of the all-pervading sandarac. It wore an air of exhausted raffishness.

The party of five being interviewed by Mr Fox and noted down by a sergeant consisted of a black plenipotentiary and his wife, the last of the governors of British Ng’ombwana and his wife, and Sir George Alleyn, Bart. They were the only members of the original party of twelve guests who had remembered anything that might conceivably have a bearing upon events in the pavilion and they remained after a painstaking winnowing had disposed of their companions.

The ex-governor, who was called Sir John Smythe, remembered that immediately after the shot was fired, everybody moved to the front of the pavilion. He was contradicted by Lady Smythe who said that for her part she had remained riveted in her chair. The plenipotentiary’s wife, whose understanding of English appeared to be rudimentary, conveyed through her husband that she, also, had remained seated. Mr Fox reminded himself that Mrs Alleyn, instructed by her husband, had not risen. The plenipotentiary recalled that the chairs had been set out in an inverted V shape with the President and his Ambassador at the apex and the guests forming the two wide-angled wings.

‘Is that the case, sir?’ said Fox comfortably, ‘I see. So that when you gentlemen stood up you’d all automatically be forward of the President? Nearer to the opening of the pavilion than he was? Would that be correct?’

‘Quite right, Mr Fox. Quite right,’ said Sir George, who had adopted a sort of uneasy reciprocal attitude towards Fox and had, at the outset, assured him jovially that he’d heard a great deal about him to which Fox replied: ‘Is that the case, sir? If I might just have your name?’

It was Sir George who remembered the actual order in which the guests had sat and although Fox had already obtained this information from Alleyn, he gravely noted it down. On the President’s left had been the Ambassador, Sir John and Lady Smythe, the plenipotentiary’s wife, the plenipotentiary, a guest who had now gone home and Sir George himself, ‘In starvation corner, what?’ said Sir George lightly to the Smythes, who made little deprecatory noises.

‘Yes, I see, thank you, sir,’ said Fox. ‘And on the President’s right hand, sir?’

‘Oh!’ said Sir George waving his hand. ‘My brother. My brother and his wife. Yes. ’Strordinary coincidence.’ Apparently feeling the need for some sort of endorsement he turned to his fellow guests. ‘My brother, the bobby,’ he explained. ‘Ridiculous, what?’

‘A very distinguished bobby,’ Sir John Smythe murmured, to which Sir George returned: ‘Oh, quite! Quite! Not for me to say but – he’ll do.’ He laughed and made a jovial little grimace.

‘Yes,’ said Fox to his notes. ‘And four other guests who have now left. Thank you, sir.’ He looked over the top of his spectacles at his hearers. ‘We come to the incident itself. There’s this report: pistol shot or whatever it was. The lights in the pavilion are out. Everybody except the ladies and the President gets to his feet. Doing what?’

‘How d’you mean, doing what?’ Sir John Smythe asked.

‘Well, sir, did everybody face out into the garden, trying to see what was going on – apart from the concert item which, I understand, stopped short when the report was heard.’

‘Speaking for myself,’ said Sir George, ‘I stayed where I was. There were signs of – ah – agitation and – ah – movement. Sort of thing that needs to be nipped in the bud if you don’t want a panic on your hands.’

‘And you nipped it, sir?’ Fox asked.

‘Well – I wouldn’t go so far – one does one’s best. I mean to say – I said something. Quietly.’

‘If there had been any signs of panic,’ said Sir John Smythe drily, ‘they did not develop.’

‘– “did not develop”,’ Mr Fox repeated. ‘And in issuing your warning, sir, did you face inwards? With your back to the garden?’

‘Yes. Yes, I did,’ said Sir George.

‘And did you notice anything at all out of the way, sir?’

‘I couldn’t see anything, my dear man. One was blinded by having looked at the brilliant light on the screen and the performer.’

‘There wasn’t any reflected light in the pavilion?’

‘No,’ said Sir George crossly. ‘There wasn’t. Nothing of the kind. It was too far away.’

‘I see, sir,’ said Fox placidly.

Lady Smythe suddenly remarked that the light on the screen was reflected in the lake. ‘The whole thing,’ she said, ‘was dazzling and rather confusing.’ There was a general murmur of agreement.

Mr Fox asked if during the dark interval anybody else had turned his or her back on the garden and peered into the interior. This produced a confused and doubtful response from which it emerged that the piercing screams of Mrs Cockburn-Montfort within the house had had a more marked effect than the actual report. The Smythes had both heard Alleyn telling the President to sit down. After the report everybody had heard the President shout out something in his own language. The plenipotentiary said it was an order. He shouted for lights. And immediately before or after that, Sir John Smythe said, he had been aware of something falling at his feet.

And then the light had gone up.

‘And I can only add, Inspector,’ said Sir John, ‘that I really have nothing else to say that can have the slightest bearing on this tragic business. The ladies have been greatly shocked and I must beg you to release them from any further ordeal.’

There was a general and heartfelt chorus of agreement. Sir George said, ‘Hear, hear,’ very loudly.

Fox said this request was very reasonable he was sure, and he was sorry to have put them all to so much trouble and he could assure the ladies that he wouldn’t be keeping them much longer. There were no two ways about it, he added, this was quite a serious affair, wasn’t it?

‘Well, then –’ said Sir John and there was a general stir.

At this juncture Alleyn came in.

In some curious and indefinable fashion he brought a feeling of refreshment with him rather like that achieved by a star whose delayed entry, however quietly executed, lifts the scene and quickens the attention of his audience.

‘We are so sorry,’ he said, ‘to have kept you waiting like this. I’m sure Mr Fox will have explained. This is a very muddling, tragic and strange affair and it isn’t made any simpler for me, at any rate, by finding myself an unsatisfactory witness and an investigating copper at one and the same time.’

He gave Lady Smythe an apologetic grin and she said – and may have been astonished to hear herself – ‘You poor man.’

‘Well, there it is and I can only hope one of you has come up with something more useful than anything I’ve been able to produce.’

His brother said: ‘Done our best. What!’

‘Good for you,’ Alleyn said. He was reading the sergeant’s notes.

‘We’re hoping,’ said Sir John, ‘to be released. The ladies –’

‘Yes, of course. It’s been a beastly experience and you must all be exhausted.’

‘What about yourself?’ asked Lady Smythe. She appeared to be a lady of spirit.

Alleyn looked up from the notes. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘you can’t slap me back. These notes seem splendidly exhaustive and there’s only one question I’d like to put to you. I know the whole incident was extremely confused, but I would like to learn if you all, for whatever reason or for no reason, are persuaded of the identity of the killer?’

‘Good God!’ Sir George shouted. ‘Really, my dear Rory! Who else could it be but the man your fellows marched off. And I must compliment you on their promptitude, by the way.’

‘You mean –?’

‘Good God, I mean the great hulking brute with the spear. I beg your pardon,’ he said to the black plenipotentiary and himself turned scarlet. ‘Afraid I spoke out of turn. Sure you understand.’

‘George,’ said his brother with exquisite courtesy, ‘would you like to go home?’