По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

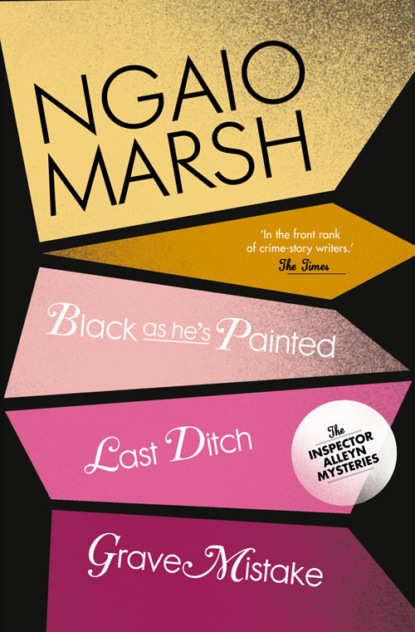

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I? We all would. Mustn’t desert the post, though. No preferential treatment.’

‘Not a morsel, I assure you. I take it, then,’ Alleyn said, turning to the others, ‘that you all believe the spear-carrier was the assailant?’

‘Well – yes,’ said Sir John Smythe. ‘I mean – there he was. Who else? And, my God, there was the spear!’

The black plenipotentiary’s wife said something rather loudly in their native tongue.

Alleyn looked a question at her husband, who cleared his throat, ‘My wife,’ he said, ‘has made an observation.’

‘Yes?’

‘My wife has said that because the body was lying beside her, she heard.’

‘Yes? She heard?’

‘The sound of the strike and the death noise.’ He held a brief consultation with his wife. ‘Also a word. In Ng’ombwanan. Spoken very low by a man. By the Ambassador himself, she thinks.’

‘And the word – in English?’

‘“Traitor”,’ said the plenipotentiary. After a brief pause he added: ‘My wife would like to go now. There is blood on her dress.’

III

The Boomer had changed into a dressing-gown and looked like Othello in the last act. It was a black and gold gown and underneath it crimson pyjamas could be detected. He had left orders that if Alleyn wished to see him he was to be roused and he now received Alleyn, Fox and an attenuated but still alert Mr Whipplestone, in the library. For a moment or two Alleyn thought he was going to jib at Mr Whipplestone’s presence. He fetched up short when he saw him, seemed about to say something but instead decided to be gracious. Mr Whipplestone, after all, managed well with The Boomer. His diplomacy was of an acceptable tinge: deferential without being fulsome, composed but not consequential.

When Alleyn said he would like to talk to the Ng’ombwanan servant who waited on them in the pavilion The Boomer made no comment but spoke briefly on the house telephone.

‘I wouldn’t have troubled you with this,’ Alleyn said, ‘but I couldn’t find anybody who was prepared to accept the responsibility of producing the man without your authority.’

‘They are all in a silly state,’ generalized The Boomer. ‘Why do you want this fellow?’

‘The English waiter in the pavilion will have it that the man attacked him.’

The Boomer lowered his eyelids. ‘How very rococo,’ he said and there was no need for him to add: ‘as we used to say at Davidson’s.’ It had been a catchphrase in their last term and worn to death in the usage. With startling precision, it again returned Alleyn to that dark room smelling of anchovy toast and a coal-fire and to the group mannerisms of his and The Boomer’s circle so many years ago.

When the man appeared he cut an unimpressive figure, being attired in white trousers, a singlet and a wrongly buttoned tunic. He appeared to be in a state of perturbation and in deep awe of his President.

‘I will speak to him,’ The Boomer announced.

He did so, and judging by the tone of his voice, pretty sharply. The man, fixing his white-eyeballed gaze on the far wall of the library, answered with, or so it seemed to Alleyn, the clockwork precision of a soldier on parade.

‘He says no,’ said The Boomer.

‘Could you press a little?’

‘It will make no difference. But I will press.’

This time the reply was lengthier. ‘He says he ran into someone in the dark and stumbled and for a moment clung to this person. It is ridiculous, he says, to speak of it as an attack. He had forgotten the incident. Perhaps it was this servant.’

‘Where did he go after this encounter?’

Out of the pavilion, it appeared, finding himself near the rear door, and frightened by the general rumpus. He had been rounded up by security men and drafted with the rest of the household staff to one end of the ballroom.

‘Do you believe him?’

‘He would not dare to lie,’ said The Boomer calmly,

‘In that case I suppose we let him go back to bed, don’t we?’

This move having been effected, The Boomer rose and so, of course, did Alleyn, Mr Whipplestone and Fox.

‘My dear Rory,’ said The Boomer, ‘there is a matter which should be settled at once. The body. It will be returned to our country and buried according to our custom.’

‘I can promise you that every assistance will be offered. Perhaps the Deputy Commissioner has already given you that assurance.’

‘Oh, yes. He was very forthcoming. A nice chap. I hear your pathologist spoke of an autopsy. There can be no autopsy.’

‘I see.’

‘A thorough enquiry will be held in Ng’ombwana.’

‘Good.’

‘And I think, since you have completed your investigations, have you not, it would be as well to find out if the good Gibson is in a similar case. If so I would suggest that the police, after leaving and at their convenience, kindly let me have a comprehensive report of their findings. In the meantime, I shall set my house in order.’

As this was in effect an order to quit, Alleyn gave his assurance that there would be a complete withdrawal of the Yard forces. The Boomer expressed his appreciation of the trouble that had been taken and said, very blandly, that if the guilty person was discovered to be a member of his own household, Alleyn, as a matter of courtesy, would be informed. On the other hand the police would no doubt pursue their security precautions outside the Embassy. These pronouncements made such sweeping assumptions that there was nothing more to be said. Alleyn had begun to take his leave when The Boomer interrupted him.

He said: ‘There is one other matter I would like to settle.’

‘Yes?’

‘About the remainder of my stay in England. It is a little difficult to decide.’

Does he, Alleyn asked himself, does The Boomer, by any blissful chance, consider taking himself back to Ng’ombwana? Almost at once? With the corpse, perhaps? What paeans of thanksgiving would spring from Gibson’s lips if it were so.

‘– the Buck House dinner party, of course, stands,’ The Boomer continued. ‘Perhaps a quieter affair will be envisaged. It is not for me to say,’ he conceded.

‘When is that?’

‘Tomorrow night. No. Tonight. Dear me, it is almost two in the morning!’

‘Your other engagements?’ Alleyn hinted.

‘I shall cancel the tree-planting affair and of course I shall not attend the race-meeting. That would not look at all the thing,’ he said rather wistfully, ‘would it?’

‘Certainly not.’

‘And then there’s the Chequers visit. I hardly know what to say.’ And with his very best top-drawer manner to the fore The Boomer turned graciously to Mr Whipplestone. ‘So difficult,’ he said, ‘isn’t it? Now, tell me. What would you advise?’