По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

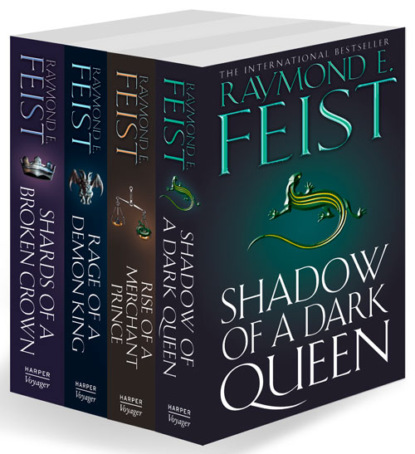

The Serpentwar Saga: The Complete 4-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Vaja looked around. ‘There’s plenty of time yet. We’ll have three or four days of this at least. Are both sides here?’

‘No word of the Emerald Queen’s agents. Just the Priest-King,’ answered Calis.

Vaja said, ‘Good. That gives me ample time to bathe and eat. You won’t be taking any offer for days.’

Calis said, ‘You know that and I know that, but if we’re to be convincing, they’ – he hiked his thumb over his shoulder in the general direction of the brokers’ tent – ‘can’t know that. We have to look as if we’re weighing all offers equally.’

‘Understood,’ said Vaja. ‘But I still have time for a bath. I’ll be back in an hour.’ He turned and led his companions away.

Praji said, ‘Twenty-nine years I’ve fought at his side, and I swear to this day no man more vain exists on this world. He’d primp for his own execution.’

Calis smiled, and Erik realized it was one of the few times he had ever seen the Captain smile.

For days they would muster on command, and brokers would come by to look over the company. With Vaja’s men and the men under Hatonis, they numbered better than one hundred swords: a significant enough troop to be taken seriously, but not so large as to bear special scrutiny.

After the third such day, offers began to come in and Calis listened to them politely. He remained noncommittal.

A week after the mustering had started, Erik noticed a few companies departing. He asked Praji about this over supper, and the old mercenary said, ‘They’ve signed on with the Priest-King. Probably poor captains running low on gold to pay their men. They have to find employment quickly or lose their fighters to richer companies. Most are waiting around to hear what the other side has to offer.’

Still more days passed and the other side didn’t appear.

Two weeks after arriving, Erik had requested permission to move the horses upriver, as they had grazed the area clean, and the hay and grain brokers were charging outrageous prices. Calis gave permission, but instructed Erik to make sure a full guard company surrounded the animals at all times.

Another week went by.

Almost a month after arriving, Erik was walking back from having checked the horses, a three-times-daily ritual now, to hear a series of loud trumpet calls from the heart of the camp. The weather was hot, the hottest part of the summer, he had been told by one of the clansmen, and soon summer would be waning. It felt odd to lose a winter, to leave in fall and return to spring. Erik was sure Nakor could explain this backwards season to him, but he wasn’t sure he was up for hearing the little man’s explanation.

Trumpets continued, insistent, and Erik started to hurry to see what the matter was. As he neared his own tent area, Foster came running toward him and shouted, ‘Get those horses down here! That’s a call to quarter! We’re being put on notice a fight’s going to break out!’

Erik dashed back up the hill and down into the next small valley, and waved his hand as he shouted to the men standing guard. ‘Bring as many as you can lead!’ He hurried past to the most distant picket line, and managed to lead four horses away. Others came hurrying past, and before he had reached the main camp, every horse was being led after him.

The men broke camp faster than Erik had ever seen. Calis gave orders for a defensive perimeter to be established, and a company began digging a breastwork. Archers scanned the hill below for signs of anyone heading their way.

Despite the sound to quarter, no sounds of battle erupted from below. Instead, a strange buzzing sound carried up the hill, and it took Erik a long minute to realize he was listening to men’s voices. Arguments and curses carried up the hillside, and the sound carried a frantic quality, but there were still no sounds of fighting.

At last Calis said, ‘Bobby, take some men down there and find out what’s going on.’

De Loungville said, ‘Biggo, von Darkmoor, Jadow, and Jerome, with me.’

Roo laughed. ‘He’s got the four biggest men in the company to hide behind.’

De Loungville turned in a single motion, looked at Roo, and said, ‘And you, my little man.’ With evil delight in his eyes, he grinned as he said, ‘You can stand on my shield side. If trouble erupts, I’m going to pick you up and throw you at the first man heading my way!’

Roo rolled his eyes heavenward and fell in beside Erik. ‘That will teach me to keep my mouth shut.’

Erik said, ‘I doubt it.’

They made their way down into the camp below on foot, trying not to call attention to themselves as they approached another campsite. Men were arguing with one another as they came within earshot.

‘I don’t care, it’s an insult. I say let’s ride south and take whatever the Priest-King offers.’

Another voice said, ‘You want to fight your way out, so you can turn around and fight again?’

Erik tried to make sense of the remarks, but de Loungville said, ‘Follow me.’

He made his way through several such camps, more than one marked by a busy attempt to get ready to ride. One man said, ‘If you break to the east, up this river, then cut through the hills to the south, you will probably get free.’

The man next to him answered, ‘What? You’re an oracle now?’

De Loungville led them to the area surrounding the brokers’ tent, where he found a knot of terrified brokers standing outside their own tent. He pushed past and entered.

A low wooden desk was used by the brokers, and behind it sat a large man in fine armor, well cared for but obviously used often. His feet rested on the polished wood, mud scattering all over the documents still upon them. He looked little different from the other soldiers in camp except that he was older, perhaps older than Praji and Vaja, the oldest men in Calis’s company. But rather than of age, his aura was that of a man of profound experience. He calmly looked at de Loungville and his companions as they entered, and nodded to another soldier who stood behind him. Both wore an emerald green armband on their left arm, but otherwise they wore no distinctive markings or uniform.

De Loungville stopped and said, ‘Well then, what fool blows a call to quarters?’

‘I have no idea,’ said the old soldier. ‘I certainly didn’t want to cause this much commotion.’

‘Are you the Emerald Queen’s agent?’

The man said, ‘I am General Gapi. I’m no one’s “agent.” I’m here to inform you of your choices.’

Erik sensed something in this man he had seen in a few others—the Prince of Krondor, Duke James, and Calis upon occasion. It was a sureness of command, an expectation that orders would be followed without debate, and Erik decided that this man’s title was no mercenary vanity. This man commanded an army.

De Loungville put his hands on his hips and said, ‘Oh, and what choices are those?’

‘You can serve the Emerald Queen or you can die.’

With a slight gesture of his head, de Loungville instructed the men around him to spread out. Erik stepped to his right, until he stood opposite the single soldier in the tent behind Gapi. De Loungville said, ‘Usually I get paid to fight. But your tone makes me think I might be willing to forgo payment this one time.’

Gapi sighed. ‘Break the peace of the camp at risk, Captain.’

‘I’m no Captain,’ said de Loungville. ‘I am a sergeant. My Captain sent me down to see what the fuss was.’

‘The fuss, as you call it,’ answered Gapi, ‘is the consternation of men too stupid to realize they have no choice. So you don’t hear a garbled version of what was said here an hour ago, I’ll repeat this so you can tell your Captain.

‘All companies of mercenaries mustering in this valley must swear fealty to the Emerald Queen. We begin our campaign downriver against Lanada in a month’s time.

‘If you attempt to leave to take service with Our Lady’s enemies, you will be hunted down and killed.’

‘And who’s doing this hunting and killing?’ asked de Loungville.

With an easy smile, Gapi said, ‘The thirty thousand soldiers who are now surrounding this pleasant little valley.’

De Loungville turned and glanced outside the tent. He searched the ridges above the valley and saw movement, a glint of light upon metal or a flicker of shadow, but enough to tell him that a sizable force was ringing the valley. Letting out an exasperated sound, he said, ‘We wondered what was taking you so long to reach here. We didn’t think you’d be coming in force.’

‘Carry word to your Captain. You have no choice.’

Looking at the General, de Loungville seemed about to say something. Then he just nodded and motioned for the others to follow him.