По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

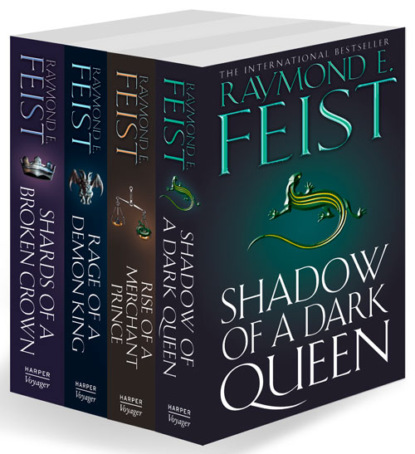

The Serpentwar Saga: The Complete 4-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Nakor was trying to move around the largest clump of celebrators so he could gain a vantage point from which to see the Emerald Queen’s pavilion. Strange energies floated on the night wind, and old, familiar echoes of distant magic sounded between the notes of song; and Nakor was coming to a conclusion about who and what he would find there.

But he wasn’t certain, and without certainty he couldn’t return to find Calis on the other side of the tributary to tell him what he must do next. The only thing of which he was certain was the need to return to Krondor, to warn Nicholas that whatever he had feared was occurring in this distant land, far worse forces were being unleashed. Subtle, behind the ancient magic of the Pantathians, a lingering scent of alien origin hung in the air.

Glancing skyward, Nakor smelled demon essences in the clouds, as if ready to fall like rain. He shook his head. ‘I’m getting tired,’ he muttered to himself as he picked his way among giant Saaur warriors.

One of Nakor’s better tricks, as he called his abilities, was the knack of moving in crowds without attracting undue notice, but it didn’t always work, and this moment was one such time.

A Saaur warrior looked down and snarled, ‘Where do you go, human?’ Its voice was deep and its accent sounded harsh to Nakor.

Nakor regarded the hooded eyes, deep red irises surrounded by white. ‘I am insignificant, O mighty one. I cannot see. I move to a place from which I may better observe this wondrous rite.’

Nakor had been curious about the Saaur when he had first reached the heart of the camp, but now he was anxious to remove himself from them. They were still a mystery to him. They bore as much resemblance to the Pantathians as humans did to elves, which was to say that superficially they looked very similar, but upon close examination they were totally unrelated. Nakor was almost certain they came from another world entirely, and that they were warm-blooded creatures, like men, elves, and dwarves, while he knew the Pantathians were not.

He would have liked to be able to discuss such theories with an educated Saaur, but all he had encountered were young male warriors with an attitude toward humans that could only be called contemptuous. He had no doubt that should the men in this camp not be servants of this Emerald Queen, the Saaur would have been delighted to murder every human in the camp. They could barely keep their antipathy for humans in check.

The average Saaur stood between nine and ten feet in height. The Saaurs were massive in chest and shoulder, but strangely delicate of neck, and while their legs were strong enough to control their massive horses, they didn’t seem to be a race of runners or jumpers. On foot, any good company of humans should prove their match, thought Nakor.

The lizard man grunted, and Nakor didn’t know if that was approval or not, but he took it as permission to move on and he did so, judging he would deal with the consequences of being wrong if he turned out to be.

He was not. The warrior returned his attention to the welcoming ritual.

The pavilion of the Emerald Queen was raised up on a giant dais, constructed either of wood or of earth – Nakor couldn’t tell which – but six feet higher than the other tents in this part of the camp. The structure was surrounded by a host of Saaur, and for the first time Nakor saw Pantathian priests beyond. Even more, he saw Pantathian warriors as well. Nakor grinned, for this was a new thing to his experience, and he always enjoyed discovering the unfamiliar.

The priest now turned and threw the slaughtered sheep onto a pyre and then cast scented oils after it. The smoke that rose was fragrant and thick, dark and coiling. The priest and the rest of the Saaur watched intently. Then the priest pointed and spoke in an alien language, but the tone was positive, and Nakor guessed he was saying the spirits were pleased with the offering or the portents were good, or some other priestly mumbo-jumbo.

Nakor squinted as a figure emerged from within the depths of the pavilion: a man in green armor, followed by another, who made way for a third, whose green armor was trimmed in gold. This powerful-looking man was General Fadawah, First Commander of the host. Nakor sensed evil hung around the man like smoke around a fire. For a soldier, he fairly reeked of magic.

Then came a woman with emeralds at her neck and wrists, dressed in a green gown cut low in front so that the fall of emeralds at her throat could be better shown. Upon her raven hair she wore a crown of emeralds.

Nakor muttered, ‘That is a lot of emeralds, even for you.’

The woman moved in a way Nakor found disturbing, and when she came forward to answer the cheers of her army, he became deeply troubled. Something was profoundly wrong!

He studied her and listened as she spoke. ‘My faithful! I who am Your Lady, who am but a vessel for one much greater, I thank you for your gifts.

‘The Sky Horde of the Saaur and the Emerald Queen promise you victory in this life and immortal reward in the next. Our spies return to tell us the unbelievers lie in wait just three days’ march to the south. Soon we shall move to crush them, then fall upon the heathen cities and reduce them to cinders. Each victory comes more swiftly than the last, and our numbers grow.’

The woman called the Emerald Queen stepped forward to the very edge of the dais and looked down on the faces of those nearest to her, both Saaur and human. Pointing to one man, she said, ‘You shall be my messenger to the gods this night!’

The man raised his fist in triumph and ran up the first four steps to the dais. He threw himself across the final two, so his head was on the floor before his mistress. She raised her foot and placed it on the man’s head for a moment in ritual, then removed it, turning to move back into the tent. The man rose with a grin, winked back at his comrades who cheered him, and followed the Queen into her pavilion.

‘Oh, this is very bad,’ whispered Nakor. He glanced around and saw the celebration was building in intensity. Soon men would be drunk and fighting, as much as was allowed, and given the lax discipline Nakor had seen in this part of the army, he suspected much brawling and even bloodshed were tolerated.

Now he would have to work his way through a company of very drunk, drug-crazed killers, and seek a way across the river to Calis – assuming he could locate Calis’s camp.

Nakor was never one to worry, and this certainly wasn’t a time to begin. Still, he was anxious that he not delay too long, for now he knew what was behind all the conflict that had been under way for the last twelve years, and what was more, he realized he might be the only man on the world who would fully understand all the different aspects of what he had just seen.

Shaking his head in consternation at the complexities of life, the little man started negotiating his way back away from the edge of the Emerald Queen’s pavilion.

A courier rode up and asked. Are ‘you Captain Calis?’

Calis said, ‘I am.’

‘Orders. You’re to take your company and ford the river’—he motioned to some place to the north of him, so Erik, who sat nearby, assumed a ford must be close at hand – ‘and conduct a sweep along the far bank, for ten miles downstream. Gilani tribesmen were seen by one of our scouts. The generals want to keep the opposite bank free of such pests.’

He turned and rode away as Praji said, ‘Pests?’ Looking after the retreating courier, he shook his head in disbelief. ‘Obviously that lad has never encountered any of the Gilani.’

‘Neither have I,’ said Calis. ‘Who are they?’

Praji spoke while he casually picked up his kit and made ready to ride out. ‘Barbarians.’ He paused and said, ‘No, savages, really. Tribespeople. No one knows who they are or where they come from. They speak a tongue only a few can master, and they rarely give anyone from outside a chance to learn it. They’re tough, and they fight like maniacs. They wander the Plain of Djams or up in the foothills of the Ratn’gary, hunting the big bison herds or chasing elk and deer.’

Picking up his own bedroll, Vaja said, ‘Most of the trouble folks on this side of the river have with them is over horses. They’re the best damn horse thieves in the world. A man’s rank is earned by how many enemies he’s killed and how many horses he’s stolen. They don’t ride them; they eat them. So I heard.’

‘Will they give us much trouble?’ said Calis.

‘Hell, we probably won’t even see one,’ answered Praji. He tossed his bedroll to Erik and said, ‘Hang on to that for me for a minute.’ He bent to get a bag that contained the rest of his personal belongings. ‘They’re tough little guys, about half again the size of dwarves,’ and with an evil grin he pointed at Roo: ‘just like him!’

The men laughed as Praji reclaimed his bedroll from Erik and they started moving toward the picket line of horses. De Loungville and Foster began calling orders to the company to ride. Praji said, ‘They can vanish into that tall grass across the river like they were spirits. They live in these low huts they put together out of woven grass, and you can be standing ten feet from one and never see it. Difficult folks to figure.’

‘But they can fight,’ said Vaja.

As they started readying their horses, Praji said, ‘That, indeed, they can do. There, Captain, now you know as much about the Gilani as just about any man born in these parts.’

Calis said, ‘Well, if they want to avoid trouble, we should be able to make a swing ten miles to the south and back before sundown.’ As if concerned over something, he looked back at the main body of the camp, then said to De Loungville, ‘Leave a squad to look after things.’ Lowering his voice, he said, ‘And tell them to keep an eye out for Nakor.’

Foster motioned to another squad that was moving to saddle their horses and gave them instructions. Erik glanced back as he lifted his saddle to place it on the back of his own mount. Where was Nakor? he wondered.

Nakor grunted as he picked up the plank, silently cursing the fool at the other end who didn’t seem to realize something existed called ‘coordinated effort.’ The man, whose name was unknown to Nakor but whom he thought of as ‘that idiot,’ insisted on lifting, moving, and dropping without bothering to mention it to Nakor. As a result, over the last two days, Nakor had accumulated an astonishing collection of splinters, scrapes, and bruises.

Nakor had encountered difficulties returning to Calis’s company. The muster had finally halted with the core army to the north of this tributary to the river Vedra, while Calis and other new mercenary companies were to the south. Passing across the smaller river was now accomplished only by riders with official-looking passes, issued by the generals. Nakor had three such passes in his bag, having stolen them two nights before, but he didn’t want to try to use one until he could study it, and there hadn’t been any place to study the documents without attracting attention. Besides the risk of losing such documents, Nakor had a predisposition not to call attention to himself unless there was a reason to do so.

But the generals had ordered a bridge rebuilt across this tributary and a work gang was diligently doing just that. Nakor figured he would pose as a worker and when the bridge reached the opposite shore, he would simply vanish into the crowd on the other bank.

Unfortunately, the work was going more slowly than he had hoped, since the labor turned out to be slave labor and, as such, the workers were in no hurry. Also, he was now being closely guarded at night. The guards might not have noticed him when he arrived – if there was an extra slave in a squad, the guard would merely assume he had miscounted in the morning – but he would be certain to notice if there was one less.

Which meant Nakor would have to wait for exactly the right moment to vanish into the companies of mercenaries. He knew that once he was free of the guards watching the work gang he would have no trouble staying free, but he wished to create as ideal a moment as possible before he attempted it. A manhunt in the southern camp might prove amusing, but Nakor knew that he must share what he had learned with Calis and the others before too long, so that they could start planning their escape from this army and their eventual return to Krondor.

‘That idiot’ dropped his end of the plank before Nakor could move, and as a result he took more splinters in his shoulder. He was about to do one of his ‘tricks’ in retaliation, a sting to the buttocks that would make the man think he had sat on a hornet, when a chill passed over him.

He glanced back and felt his chest tighten, for a Pantathian priest stood not ten feet away watching the construction, speaking quietly to a human officer. Nakor set down his end of the plank and hurried back for another, keeping his eyes down. Nakor had encountered the Pantathians and their handiwork before, while traveling with the man who was now Prince of Krondor, but he had never seen a living Pantathian that close. As he passed the creature he noticed a faint odor, and remembered having heard of this smell before: very reptilian, yet alien.

Nakor bent to pick up another plank and saw ‘that idiot’ stumble over a rock. He lost his balance and took a half-step toward the Pantathian. The creature reacted, turning with a clawed hand sweeping out. The talons struck across the idiot’s chest, ripping his tunic as if they were knives. Deep cuts of crimson appeared as the man cried out. Then he went weak in the knees and collapsed, to lie twitching on the ground.

The human officer said to Nakor, ‘Get him out of here,’ and Nakor and another slave grabbed the fallen man. By the time they had moved him back to the slaves’ compound, the man was dead. Nakor studied the face, frozen in death with eyes open, and watched closely. After a few minutes, he was certain he knew exactly what poison the Pantathian had on his claws. It was no natural venom, but something created by mixing several deadly plant toxins together, and Nakor found this revelation fascinating.

He was also fascinated by the Pantathian’s need to demonstrate before the human officer his deadly ability to kill with a touch. There were politics here in the camp of the Emerald Queen that were not obvious to those far from the heart of power, and Nakor wished he had the time to try to uncover more about them. Any struggle in the enemy camp was good to know about, but unfortunately, he couldn’t afford to spend the time insinuating himself where he could observe the byplays of power.

A guard said, ‘Drop him there,’ pointing to a garbage heap that would be hauled away by wagon at sundown and dumped at a fill a mile or so away from the river. Nakor did as he was bid, and the guard ordered the two slaves to return to work.