По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

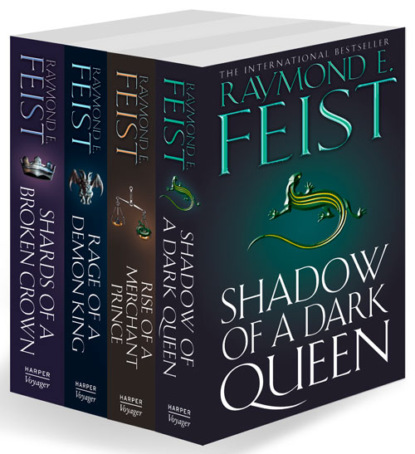

The Serpentwar Saga: The Complete 4-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Nakor hurried down to the building site, but the Pantathian and the human officer were now gone. He felt a brief regret that he couldn’t study the Serpent priest any longer, and even more regret that ‘that idiot’ had been killed. The man had deserved to have his backside stung, but he hadn’t deserved to die painfully as a poison shut down his lungs and heart.

Nakor worked until the noon meal. He sat on the bridge, now only a few yards from the other bank, dangling his feet above the water as he ate the tasteless gruel and hard bread to keep his strength up. All the while he ate, he wondered what Calis and the others were doing.

Calis motioned for the outriders on the right flank to keep an even line of sight, one man to the next, for a half mile. Signals from the closest man indicated the order was understood.

They had been riding since noon and still had no sign of anyone near the bank. Either the report of those tribesmen being nearby was in error, or they had left the area, or they were, as Praji had said, able to keep themselves from being seen.

Erik watched for any unexpected movement in the grass, but it was a breezy afternoon, and the tall grass moved like water. It would take eyes far better than his to see someone moving through this sheltering plain.

A short time later, Calis said, ‘If we don’t find something within the next half hour, we should return. We’ll be getting back to the ford in the dark as it is now.’

A shout from an outrider, and everyone looked to the west. Erik used his hand to shade his eyes against the afternoon sunlight, and saw a rider frantically signaling from the base of a large mound. Calis motioned and the column turned toward the rider.

When they reached the base of the hillock, Erik could see it was covered in the same grass as the plains, making it look like nothing so much as an inverted shaggy bowl. Almost completely round, it was some distance from the next rise, the beginning of a series of hills leading toward the distant mountains.

‘What is it?’ asked Calis.

‘Tracks and a cave. Captain,’ answered the outrider.

Praji and Vaja exchanged questioning looks, and dismounted. They led their horses close to the cave and inspected it. A short entrance, one a man could enter stooped over, led back into the gloom.

Calis glanced down. ‘Old tracks.’ Then he moved to the entrance and ran his hand over the stone edge of the cave. ‘This isn’t natural,’ said Calis.

‘Or if it is,’ said Praji, also running his hand along the wall, ‘someone’s done some work on it to make it more sturdy. There’s stonework under this dirt.’ He brushed away the dirt and revealed some fitted stones underneath.

‘Sarakan,’ said Vaja.

‘Maybe,’ conceded Praji.

‘Sarakan?’ asked Calis.

Praji remounted his horse and said, ‘It’s an abandoned dwarven city in the Ratn’gary Mountains. All of it underground. Some humans moved in a few centuries back, some cult of lunatics, and they’ve died out. Now it just sits empty.’

‘People are always stumbling across entrances down near the Gulf,’ said Vaja, ‘and in the foothills near the Great South Forest.’

Calis said, ‘Correa me if I’m wrong, but that’s hundreds of miles from here.’

‘True,’ said Praji. ‘But the damn tunnels run everywhere.’ He pointed to the hillock. ‘That one could be connected somewhere over there’ – he pointed at the distant mountains – ‘or it could simply go back a few hundred feet and stop. Depends on who built it, but it looks like one of the entrances to Sarakan.’

Roo ventured, ‘Maybe it’s built by the same dwarves, but it’s a different city?’

‘Maybe,’ said Praji. ‘It’s been a long time since any dwarves lived anywhere but the mountains, and city folk don’t linger on the Plain of Djams.’

Calis said, ‘Could we use this as a depot? Leave some weapons and supplies here if we need to come down this side of the river?’

Praji said, ‘I wouldn’t, Captain. If the Gilani are around here, they may be using this as a base.’

Calis was silent for a moment; then he spoke loudly enough for the entire troop, except for the other outriders, to hear. ‘Mark this location in your minds. Check the distant landscapes. We may be very needful of finding this exact spot, soon. If we need to break from the camp, for any reason, or fight our way out, if you can’t make straight for the city of Lanada, make for this mound. Those who do meet here, make your way to the south the best you can. The City of the Serpent River is your final goal, for one of our ships should be waiting there.’

Erik looked around and then looked down at his mount. If he put her nose in line with two peaks in the distant mountains, the one that looked like a broken fang, and the other that looked like a clump of grapes, to his imagination, and kept the river at his back while keeping another distant peak off his left side, he thought he should be able to find his way back here.

After the men had taken their bearings. Calis turned to an outrider up on a distant hill who was watching. Calis made the arm signals to indicate they were turning back.

The man acknowledged the order, then turned and signaled an even more distant rider, while Calis gave the order to return to the host of the Emerald Queen.

• Chapter Eighteen • Escape (#ulink_0525b256-2f7e-521a-aa09-c0d4196b91fc)

Nakor waved.

He had learned years ago that if you didn’t want to be accosted by minor officials, look as if you know exactly what you’re doing. The officer standing on the far end of the dock didn’t recognize Nakor, as the Isalani knew he wouldn’t. Slaves weren’t people. One didn’t take note of them.

And now he didn’t look like a slave. He had ducked out of the slave pen the night before so that the morning and night head count would match. He had wandered around the camp, smiling and chatting, until he had reached the place where he had secreted his belongings when he had run off to play construction worker.

Then at dawn he had wandered back to the slave pens and fallen in a few yards behind the work gang. He had moved along the newly constructed bridge, past a guard who started to ask him something when Nakor patted him on the shoulder in a friendly fashion and said, ‘Good morning,’ leaving the guard scratching his chin.

Now he called to the officer, ‘Here, catch!’ and threw him his bundle of bedroll and shoulder sack. The officer reacted without thought and caught the bundle, then set it down as if it were covered in bugs.

By then Nakor had jumped the five feet separating the end of the bridge and the south-shore foundation of rocks. He landed and stood up, saying, ‘I didn’t want to take the chance of dropping the bundle in the water. There are important documents in it.’

‘Important …?’ asked the officer as Nakor picked up his bundle.

‘Thank you. I must be getting those orders to the Captain.’

The officer hesitated, which was his undoing, for in that moment, while he tried to frame his next question, Nakor slipped behind a party of horsemen riding past, and when they had moved on, the little man was nowhere in sight.

The officer stood peering this way and that, and failed to notice that a few feet away there were now seven sleeping mercenaries around a cold campfire where moments before there had been only six. Nakor lay motionless, listening for any sign of alarm.

He grinned as he lay there, his usual reaction to pulling off a good vanishing act. He found it amazing that most people never noticed what was going on right before their noses. He took a deep breath, closed his eyes, and started to doze.

Less than an hour later, he heard a voice and opened his eyes. One of the soldiers next to him was sitting up and yawning. Nakor turned over and saw that the officer he had flummoxed was standing with his back toward the camp.

Nakor rolled to his feet, said, ‘Good morning,’ to the still-half-asleep mercenary, and moved off down the trail toward where he hoped Calis was camped.

Erik looked up from where he sat, a few feet away from Calis, de Loungville, and Foster, polishing his sword. They had returned to camp after nightfall, and Calis had gone to report to the officers’ tent near the bridge while Erik and the others tended the horses. When he returned he showed no sign of how the meeting went, but Calis rarely showed anything that Erik could read as pleasure or irritation.

But now Erik saw a small betrayal of emotion as Calis rose with an expectant expression: Nakor was making his way across the narrow trail that had been worn by hooves and feet between the Eagles’ camp and the one to the east.

The little man came trudging into view, with his seemingly ever-present grin in place. ‘Woof,’ he said, sitting down heavily on the ground next to Foster. ‘That was some doing, finding you. Lots of bird banners, and lots of red things, and most of these men’ – he pointed in general at most of the other companies nearby – ‘don’t care who’s next to them. This is one very ignorant bunch.’

Praji, who was lying back picking his teeth with a long sliver of wood, said, ‘They’re not being paid to think.’

‘True.’

‘What did you discover?’ asked Calis.

Nakor leaned forward and lowered his voice, so that Erik had to strain to overhear, though he and the others in his squad were trying hard to look as if they weren’t. ‘I don’t think it’s such a good idea to talk about this here, but let’s say that when I can tell you, you don’t want to know what I saw.’

‘Yes I do,’ said Calis.