По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

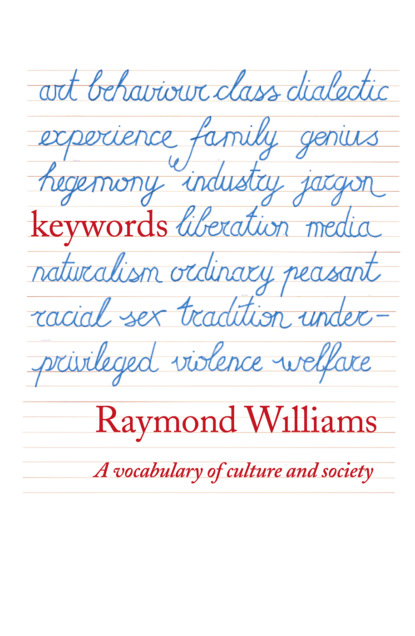

Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Abbreviations (#ub72a76ee-3122-5c75-999c-ab652d4a55ad)

The following abbreviations are used in the text.

Quotations followed by a name and date only, or a date only, are from examples cited in OED. Other quotations are followed by specific sources. References to secondary works are by author’s name, as entered in References and Select Bibliography.

A (#ub72a76ee-3122-5c75-999c-ab652d4a55ad)

AESTHETIC (#ulink_bf7fce66-9e94-5c8f-a227-ca99e961b0ce)

Aesthetic first appeared in English in C19, and was not common before mC19. It was in effect, in spite of its Greek form, a borrowing from German, after a critical and controversial development in that language. It was first used in a Latin form as the title of two volumes, Aesthetica (1750–8), by Alexander Baumgarten (1714–62). Baumgarten defined beauty as phenomenal perfection, and the importance of this, in thinking about art, was that it placed a predominant stress on apprehension through the senses. This explains Baumgarten’s essentially new word, derived from rw aisthesis, Gk – sense perception. In Greek the main reference was to material things, that is things perceptible by the senses, as distinct from things which were immaterial or which could only be thought. Baumgarten’s new use was part of an emphasis on subjective sense activity, and on the specialized human creativity of art, which became dominant in these fields and which inherited his title-word, though his book was not translated and had limited circulation. In Kant beauty was also seen as an essentially and exclusively sensuous phenomenon, but he protested against Baumgarten’s use and defined aesthetics in the original and broader Greek sense of the science of ‘the conditions of sensuous perception’. Both uses are then found in occasional eC19 English examples, but by mC19 reference to ‘the beautiful’ is predominant and there is a strong regular association with art. Lewes, in 1879, used a variant derived form, aesthesics, in a definition of the ‘abstract science of feeling’. Yet anaesthesia, a defect of physical sensation, had been used since eC18; and from mC19, with advances in medicine, anaesthetic – the negative form of the increasingly popular adjective – was widely used in the original broad sense to mean deprived of sensation or the agent of such deprivation. This use of the straight negative form led eventually to such negatives as unaesthetic or nonaesthetic in relation to the dominant use referring to beauty or to art.

In 1821 Coleridge wished that he could ‘find a more familiar word than aesthetics for works of TASTE and CRITICISM’ (qq.v.), and as late as 1842 aesthetics was referred to as ‘a silly pedantical term’. In 1859 Sir William Hamilton, understanding it as ‘the Philosophy of Taste, The theory of the Fine Arts, the Science of the Beautiful, etc.’, and acknowledging its general acceptance ‘not only in Germany but throughout the other countries of Europe’, still thought apolaustic would have been more appropriate. But the word had taken hold and became increasingly common, though with a continuing uncertainty (implicit in the theory which had led to the coinage) between reference to art and more general reference to the beautiful. By 1880 the noun aesthete was being widely used, most often in a derogatory sense. The principles and practices of the ‘aesthetic movement’ around Walter Pater were both attacked and sneered at (the best-remembered example is in Gilbert’s Patience (1880)). This is contemporary with similar feeling around the use of culture by Matthew Arnold and others. Aesthete has not recovered from this use, and the neutral noun relating to aesthetics as a formal study is the earlier (mC19) aesthetician. The adjective aesthetic, apart from its specialized uses in discussion of art and literature, is now in common use to refer to questions of visual appearance and effect.

It is clear from this history that aesthetic, with its specialized references to ART (q.v.), to visual appearance, and to a category of what is ‘fine’ or ‘beautiful’, is a key formation in a group of meanings which at once emphasized and isolated SUBJECTIVE (q.v.) sense-activity as the basis of art and beauty as distinct, for example, from social or cultural interpretations. It is an element in the divided modern consciousness of art and society: a reference beyond social use and social valuation which, like one special meaning of culture, is intended to express a human dimension which the dominant version of society appears to exclude. The emphasis is understandable but the isolation can be damaging, for there is something irresistibly displaced and marginal about the now common and limiting phrase ‘aesthetic considerations’, especially when contrasted with practical or UTILITARIAN (q.v.) considerations, which are elements of the same basic division.

See ART, CREATIVE, CULTURE, GENIUS, LITERATURE, SUBJECTIVE, UTILITARIAN

ALIENATION (#ulink_fc0bbb84-4feb-5f80-a0ff-89f526022220)

Alienation is now one of the most difficult words in the language. Quite apart from its common usage in general contexts, it carries specific but disputed meanings in a range of disciplines from social and economic theory to philosophy and psychology. From mC20, moreover, it has passed from different areas of this range into new kinds of common usage where it is often confusing because of overlap and uncertainty in relation both to the various specific meanings and the older more general meanings.

Though it often has the air of a contemporary term, alienation as an English word, with a wide and still relevant range of meanings, has been in the language for several centuries. Its fw is aliénacion, mF, from alienationem, L, from rw alienare – to estrange or make another’s; this relates to alienus, L – of or belonging to another person or place, from rw alius – other, another. It has been used in English from C14 to describe an action of estranging or state of estrangement (i): normally in relation to a cutting-off or being cut off from God, or to a breakdown of relations between a man or a group and some received political authority. From C15 it has been used to describe the action of transferring the ownership of anything to another (ii), and especially the transfer of rights, estates or money. There are subsidiary minor early senses of (ii), where the transfer is contrived by the beneficiary (stealth) or where the transfer is seen as diversion from a proper owner or purpose. These negative senses of (ii) eventually became dominant; a legal sense of voluntary and intentional transfer survived, but improper, involuntary or even forcible transfer became the predominant implication. This was then extended to the result of such a transfer, a state of something having been alienated (iii). By analogy, as earlier in Latin, the word was further used from C15 to mean the loss, withdrawal or derangement of mental faculties, and thus insanity (iv).

In the range of contemporary specific meanings, and in most consequent common usage, each of these earlier senses is variously drawn upon. By eC20 the word was in common use mainly in two specific contexts: the alienation of formal property, and in the phrase alienation of affection (from mC19) with the sense of deliberate and contrived interference in a customary family relationship, usually that of husband and wife. But the word had already become important, sometimes as a key concept, in powerful and developing intellectual systems.

There are several contemporary variants of sense (i). There is the surviving theological sense, normally a state rather than an action, of being cut off, estranged from the knowledge of God, or from his mercy or his worship. This sometimes overlaps with a more general use, with a decisive origin in Rousseau, in which man is seen as cut off, estranged from his own original nature. There are several variants of this, between the two extreme defining positions of man estranged from his original (often historically primitive) nature and man estranged from his essential (inherent and permanent) nature. The reasons given vary widely. There is a persistent sense of the loss of original human nature through the development of an ‘artificial’ CIVILIZATION (q.v.); the overcoming of alienation is then either an actual primitivism or a cultivation of human feeling and practice against the pressures of civilization. In the case of estrangement from an essential nature the two most common variants are the religious sense of estrangement from ‘the divine in man’, and the sense common in Freud and Freudian-influenced psychology in which man is estranged (again by CIVILIZATION or by particular phases or processes of CIVILIZATION) from his primary energy, either libido or explicit sexuality. Here the overcoming of alienation is either recovery of a sense of the divine or, in the alternative tradition, whole or partial recovery of libido or sexuality, a prospect viewed from one position as difficult or impossible (alienation in this sense being part of the price paid for civilization) and from another position as programmatic and radical (the ending of particular forms of repression – CAPITALISM, the BOURGEOIS FAMILY (qq.v.) – which produce this substantial alienation).

There is an important variation of sense (i) by the addition of forms of sense (ii) in Hegel and, alternatively, in Marx. Here what is alienated is an essential nature, a ‘self-alienated spirit’, but the process of alienation is seen as historical. Man indeed makes his own nature, as opposed to concepts of an original human nature. But he makes his own nature by a process of objectification (in Hegel a spiritual process; in Marx the labour process) and the ending of alienation would be a transcendence of this formerly inevitable and necessary alienation. The argument is difficult and is made more difficult by the relations between the German and English key words. German entäussern corresponds primarily to English sense (ii): to part with, transfer, lose to another, while having also an additional and in this context crucial sense of ‘making external to oneself’. German entfremden is closer to English sense (i), especially in the sense of an act or state of estrangement between persons. (On the history of Entfremdung, see Schacht. A third word used by Marx, vergegenständlichung, has been sometimes translated as alienation but is now more commonly understood as ‘reification’ – broadly, making a human process into an objective thing.) Though the difficulties are clearly explained in some translations, English critical discussion has been confused by uncertainty between the meanings and by some loss of distinction between senses (i) and (ii): a vital matter when in the development of the concept the interactive relation between senses (i) and (ii) is crucial, as especially in Marx. In Hegel the process is seen as world-historical spiritual development, in a dialectical relation of subject and object, in which alienation is overcome by a higher unity. In a subsequent critique of religion, Feuerbach described God as an alienation – in the sense of projection or transfer – of the highest human powers; this has been repeated in modern humanist arguments and in theological apologetics. In Marx the process is seen as the history of labour, in which man creates himself by creating his world, but in class-society is alienated from this essential nature by specific forms of alienation in the division of labour, private property and the capitalist mode of production in which the worker loses both the product of his labour and his sense of his own productive activity, following the expropriation of both by capital. The world man has made confronts him as stranger and enemy, having power over him who has transferred his power to it. This relates to the detailed legal and commercial sense of alienation (ii) or Entäusserung, though described in new ways by being centred in the processes of modern production. Thus alienation (i), in the most general sense of a state of estrangement, is produced by the cumulative and detailed historical processes of alienation (ii). Minor senses of alienation (i), corresponding to Entfremdung – estrangement of persons in competitive labour and production, the phenomenon of general estrangement in an industrial-capitalist factory or city – are seen as consequences of this general process.

All these specific senses, which have of course been the subject of prolonged discussion and dispute from within and from outside each particular system, have led to increasing contemporary usage, and the usual accusations of ‘incorrectness’ or ‘misunderstanding’ between what are in fact alternative uses of the word. The most widespread contemporary use is probably that derived from one form of psychology, a loss of connection with one’s own deepest feelings and needs. But there is a very common combination of this with judgments that we live in an ‘alienating’ society, with specific references to the nature of modern work, modern education and modern kinds of community. A recent classification (Seeman, 1959) defined: (a) powerlessness – an inability or a feeling of inability to influence the society in which we live; (b) meaninglessness – a feeling of lack of guides for conduct and belief, with (c) normlessness – a feeling that illegitimate means are required to meet approved goals; (d) isolation – estrangement from given norms and goals; (e) self-estrangement – an inability to find genuinely satisfying activities. This abstract classification, characteristically reduced to psychological states and without reference to specific social and historical processes, is useful in showing the very wide range which common use of the term now involves. Durkheim’s term, anomie, which has been also adopted in English, overlaps with alienation especially in relation to (b) and (c), the absence of or the failure to find adequate or convincing norms for social relationship and self-fulfilment.

It is clear from the present extent and intensity of the use of alienation that there is widespread and important experience which, in these varying ways, the word and its varying specific concepts offer to describe and interpret. There has been some impatience with its difficulties, and a tendency to reject it as merely fashionable. But it seems better to face the difficulties of the word and through them the difficulties which its extraordinary history and variation of usage indicate and record. In its evidence of extensive feeling of a division between man and society, it is a crucial element in a very general structure of meanings.

See CIVILIZATION, INDIVIDUAL, MAN, PSYCHOLOGICAL, SUBJECTIVE

ANARCHISM (#ulink_ca0a0227-10ea-5fd2-a62f-08893111bc7d)

Anarchy came into English in mC16, from fw anarchie, F, rw anarchia, Gk – a state without a leader. Its earliest uses are not too far from the early hostile uses of DEMOCRACY (q.v.): ‘this unleful lyberty or lycence of the multytude is called an Anarchie’ (1539). But it came through as primarily a description of any kind of disorder or chaos (Gk – chasm or void). Anarchism, from mC17, and anarchist, from lC17, remained, however, much nearer the political sense: ‘Anarchism, the Doctrine, Positions or Art of those that teach anarchy; also the being itself of the people without a Prince or Ruler’ (1656). The anarchists thus characterized are very close to democrats and republicans, in their older senses; there was also an association of anarchists and atheists (Cudworth, 1678). It is interesting that as late as 1862 Spencer wrote: ‘the anarchist … denies the right of any government … to trench upon his individual freedom’; these are now often the terms of a certain modern liberalism or indeed of a radical conservatism.

However the terms began to shift in the specific context of the French Revolution, when the Girondins attacked their radical opponents as anarchists, in the older general sense. This had the effect of identifying anarchism with a range of radical political tendencies, and the term of abuse seems first to have been positively adopted by Proudhon, in 1840. From this period anarchism is a major tendency within the socialist and labour movements, often in conflict with centralizing versions of Marxism and other forms of SOCIALISM (q.v.). From the 1870s groups which had previously defined themselves as mutualists, federalists or anti-authoritarians consciously adopted anarchists as their identification, and this broad movement developed into revolutionary organizations which were opposed to ‘state socialism’ and to the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’. The important anarcho-syndicalist movement founded social organization on self-governing collectives, based on trade unions; these would be substituted for all forms of state organization.

Also, however, mainly between the 1870s and 1914, one minority tendency in anarchism had adopted tactics of individual violence and assassination, against political rulers. A strong residual sense of anarchist as this kind of terrorist (in the language, with terrorism, from Cl8) has not been forgotten, though it is clearly separate from the mainstream anarchist movement.

Conscious self-styled anarchism is still a significant political movement, but it is interesting that many anarchist ideas and proposals have been taken up in later phases of Marxist and other revolutionary socialist thought, though the distance from the word, with all its older implications, is usually carefully maintained.

See DEMOCRACY, LIBERAL, LIBERATION, RADICAL, REVOLUTION, SOCIALISM, VIOLENCE

ANTHROPOLOGY (#ulink_90083ac0-ef7a-572f-9cc5-3b8e08b30b90)

Anthropology came into English in lC16. The first recorded use, from R. Harvey in 1593, has a modern ring: ‘Genealogy or issue which they had, Artes which they studied, Actes which they did. This part of History is named Anthropology.’ Yet a different sense was to become predominant, for the next three centuries. Anthropologos, Gk – discourse and study of man, with the implied substantive form anthropologia, had been used by Aristotle, and was revived in 1594–5 by Casmann: Psychologica Anthropologica, sive Animae Humanae Doctrina and Anthropologia: II, hoc est de fabrica Humani Corporis. The modern terms for the two parts of Casmann’s work would be PSYCHOLOGY (q.v.) and physiology, but of course the point was the linkage, in a sense that was still active in a standard C18 definition: ‘Anthropology includes the consideration both of the human body and soul, with the laws of their union, and the effects thereof, as sensation, motion, etc.’ What then came through was a specialization of physical studies, either (i) in relation to the senses – ‘the analysis of our senses in the commonest books of anthropology’ (Coleridge, 1810) – or (ii) in application to problems of human physical diversity (cf. RACIAL) and of human EVOLUTION (q.v.). Thus until the later C19, the predominant meaning was in the branch of study we now distinguish as ‘physical anthropology’.

The emergence (or perhaps, remembering Harvey, the re-emergence) of a more general sense, for what we would now distinguish as ‘social’ or ‘cultural’ anthropology, is a C19 development closely associated with the development of the ideas of CIVILIZATION (q.v.) and especially CULTURE (q.v.). Indeed Tylor’s Primitive Culture (1870) is commonly taken, in the English-speaking world, as a founding text of the new science. This runs back, in one line, to Herder’s lC18 distinction of plural cultures – distinct ways of life, which need to be studied as wholes, rather than as stages of DEVELOPMENT (q.v.) towards European civilization. It runs back also, in another line, to concepts derived from this very notion (common in the thinkers of the C18 Enlightenment) of ‘stages’ of development, and notably to G. F. Klemm’s Allgemeine Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit – ‘General Cultural History of Mankind’ (1843–52) and Allgemeine Kulturwissenschaft – ‘General Science of Culture’ (1854–5). Klemm distinguished three stages of human development as savagery, domestication and freedom. In 1871 the American Lewis Morgan, a pioneer in linguistic studies of kinship, influentially defined three stages in his Ancient Society; or Researches in the Line of Human Progress from Savagery through Barbarism to Civilization. Through Engels this had a major influence on early Marxism. But the significance of this line for the idea of anthropology was its emphasis on ‘primitive’ (or ‘savage’) cultures, whether or not in a perspective of ‘development’. In the period of European imperialism and colonialism, and in the related period of American relations with the conquered Indian tribes, there was abundant material both for scientific study and for more general concerns. (Some of the latter were later systematized as ‘practical’ or ‘applied’ anthropology, bringing scientific knowledge to bear on governmental and administrative policies.) Yet the most important effect was the relative specialization of anthropology to ‘primitive’ cultures, though this work, when done, both provided models of studies of ‘whole and distinct ways of life’, with effects on the study of ‘human structures’, generalized in one tendency as STRUCTURALISM (q.v.) in the closely related linguistics and anthropology; in another tendency as functionalism, in which social institutions are (variable) cultural responses to basic human needs; and, in its assembly of wide comparative evidence, encouraging more generally the idea of alternative cultures and lines of human development, in sharp distinction from the idea of regular stages in a unilinear process towards civilization.

Thus, in mC20, there were still the longstanding physical anthropology; the rich and extending anthropology of ‘primitive’ peoples; and, in an uncertain area beyond both, the sense of anthropology as a mode of study and a source of evidence for more general including modern human ways of life. Of course by this period SOCIOLOGY (q.v.) had become established, in different forms, as the discipline in which modern societies (and, in some schools, modern cultures) were studied, and there were then difficult overlaps with what were now called (mainly to distinguish them from physical anthropology) ‘social’ or ‘cultural’ anthropology (‘social’ has been more common in Britain; ‘cultural’ in USA; though culturalanthropology, in USA, often indicates the study of material artefacts).

The major intellectual issues involved in this complex of terms and disciplines are sometimes revealed, perhaps more often obscured, by the complex history of the words. It is interesting that a new grouping of these closely related and often overlapping concerns and disciplines is increasingly known, from mC20, as ‘the human sciences’ (especially in France ‘les sciences humaines’), which is in effect starting again, in a modern language, and in the plural, with what had been the literal but then variously specialized meaning of anthropology.

See CIVILIZATION, CULTURE, DEVELOPMENT, EVOLUTION, PSYCHOLOGY, RACIAL, SOCIOLOGY, STRUCTURAL

ART (#ulink_b84839b3-9400-58bf-8101-8141bfa7f56d)

The original general meaning of art, to refer to any kind of skill, is still active in English. But a more specialized meaning has become common, and in the arts and to a large extent in artist has become predominant.

Art has been used in English from C13, fw art, oF, rw artem, L – skill. It was widely applied, without predominant specialization, until lC17, in matters as various as mathematics, medicine and angling. In the medieval university curriculum the arts (‘the seven arts’ and later ‘the LIBERAL (q.v.) arts’) were grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy, and artist, from C16, was first used in this context, though with almost contemporary developments to describe any skilled person (as which it is in effect identical with artisan until lC16) or a practitioner of one of the arts in another grouping, those presided over by the seven muses: history, poetry, comedy, tragedy, music, dancing, astronomy. Then, from lC17, there was an increasingly common specialized application to a group of skills not hitherto formally represented: painting, drawing, engraving and sculpture. The now dominant use of art and artist to refer to these skills was not fully established until lC19, but it was within this grouping that in lC18, and with special reference to the exclusion of engravers from the new Royal Academy, a now general distinction between artist and artisan – the latter being specialized to ‘skilled manual worker’ without ‘intellectual’ or ‘imaginative’ or ‘creative’ purposes – was strengthened and popularized. This development of artisan, and the mC19 definition of scientist, allowed the specialization of artist and the distinction not now of the liberal but of the fine arts.

The emergence of an abstract, capitalized Art, with its own internal but general principles, is difficult to localize. There are several plausible C18 uses, but it was in C19 that the concept became general. It is historically related, in this sense, to the development of CULTURE and AESTHETICS (qq.v.). Wordsworth wrote to the painter Haydon in 1815: ‘High is our calling, friend, Creative Art.’ The now normal association with creative and imaginative, as a matter of classification, dates effectively from lC18 and eC19. The significant adjective artistic dates effectively from mC19. Artistic temperament and artistic sensibility date from the same period. So too does artiste, a further distinguishing specialization to describe performers such as actors or singers, thus keeping artist for painter, sculptor and eventually (from mC19) writer and composer.

It is interesting to notice what words, in different periods, are ordinarily distinguished from or contrasted with art. Artless before mC17 meant ‘unskilled’ or ‘devoid of skill’, and this sense has survived. But there was an early regular contrast between art and nature: that is, between the product of human skill and the product of some inherent quality. Artless then acquired, from mC17 but especially from lC18, a positive sense to indicate spontaneity even in ‘art’. While art still meant skill and INDUSTRY (q.v.) diligent skill, they were often closely associated, but when each was abstracted and specialized they were often, from eC19, contrasted as the separate areas of imagination and utility. Until C18 most sciences were arts; the modern distinction between science and art, as contrasted areas of human skill and effort, with fundamentally different methods and purposes, dates effectively from mC19, though the words themselves are sometimes contrasted, much earlier, in the sense of ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ (see SCIENCE, THEORY).

This complex set of historical distinctions between various kinds of human skill and between varying basic purposes in the use of such skills is evidently related both to changes in the practical division of labour and to fundamental changes in practical definitions of the purposes of the exercise of skill. It can be primarily related to the changes inherent in capitalist commodity production, with its specialization and reduction of use values to exchange values. There was a consequent defensive specialization of certain skills and purposes to the arts or the humanities where forms of general use and intention which were not determined by immediate exchange could be at least conceptually abstracted. This is the formal basis of the distinction between art and industry, and between fine arts and useful arts (the latter eventually acquiring a new specialized term, in TECHNOLOGY (q.v.)).

The artist is then distinct within this fundamental perspective not only from scientist and technologist – each of whom in earlier periods would have been called artist – but from artisan and craftsman and skilled worker, who are now operatives in terms of a specific definition and organization of WORK (q.v.). As these practical distinctions are pressed, within a given mode of production, art and artist acquire ever more general (and more vague) associations, offering to express a general human (i.e. non-utilitarian) interest, even while, ironically, most works of art are effectively treated as commodities and most artists, even when they justly claim quite other intentions, are effectively treated as a category of independent craftsmen or skilled workers producing a certain kind of marginal commodity.

See AESTHETIC, CREATIVE, CULTURE, GENIUS, INDUSTRY, SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY

B (#ulink_c5bcbbd3-0985-549c-8715-dd35ba50db86)

BEHAVIOUR (#ulink_c5bcbbd3-0985-549c-8715-dd35ba50db86)

Behave is a very curious word which still presents difficulties. There was an oE behabban – to contain, from rw be – about, habban – to hold. But the modern word seems to have been introduced in C15 as a form of qualification of the verb have (cf. sich behaben, in G), and especially in the reflexive sense of ‘to have (bear) oneself’. In C16 examples the past tense can be behad. The main sense that came through was one of public conduct or bearing: the nearest modern specialization would perhaps be deportment, or the specialized sense (from C16) of manners (cf. C14 mannerly). In the verb this is still a predominant sense, and to behave (‘yourself’) is still colloquially to behave well, although to behave badly is also immediately understood. In the course of its development from its originally rather limited and dignified sense of public conduct (which Johnson still noted with an emphasis on external), to a term summarizing, in a general moral sense, a whole range of activities, behave has acquired a certain ambivalence, and this has become especially important in the associated development of behaviour. Use of the noun to refer to public conduct or, in a moral sense, to a general range of activities is still common enough; the classic instance is ‘when we are sick in fortune, often the surfeits of our own behaviour’ (King Lear, I, ii). But the critical development is the neutral application of the term, without any moral implications, to describe ways in which someone or something acts (reacts) in some specific situation. This began in scientific description in Cl7 but is not common before C19. The crucial transfer seems to take place in descriptions of material objects, with a strong sense of observation which is probably related to the earlier main sense of observable public conduct. Thus: ‘to watch … the behaviour of the water which drains off a flat coast of mud’ (Huxley, 1878). But the term was also used in relation to plants, lower organisms and animals, and by lC19 was in general use in its still current sense of ‘the externally apparent activity of a whole organism’. (Cf. animal behaviour, and its specialized synonym ethology; ethology had previously been defined as mimicry, Cl7; the science of ethics, C18; the science of character (Mill, 1843). The range from moral to neutral definitions is as evident as in behaviour, and can of course be seen also in character.)

One particular meaning followed from the extension of the methodology of the physical and biological sciences to an influential school of psychology which described itself (Watson, 1913) as behaviourist and (slightly later) behaviourism. Psychology was seen as ‘a purely objective experimental branch of natural science’ (Watson), and data of a ‘mental’ or ‘experiential’ kind were ruled out as unscientific. The key point in this definition was the sense of observable, which was initially confined to ‘objectively physically measurable’ but which later developments, that were still called behaviourist or neo-behaviourist (this use of neo, Gk – new, to indicate a new or revised version of a doctrine is recorded from C17 but is most common from lC19), modified to ‘experimentally measurable’, various kinds of ‘mental’ or ‘experiential’ (cf. SUBJECTIVE) data being admitted under conditions of controlled observation. More important, probably, than the methodological argument within psychology was the extension, from this school and from several associated social and intellectual tendencies, of a sense of behaviour, in its new wide reference to all (? observable) activity, and especially human activity, as ‘interaction’ between ‘an organism’ and ‘its environment’, usually itself specialized to ‘stimulus’ and ‘response’. This had the effect, in a number of areas, of limiting not only the study but the nature of human activity to interactions DETERMINED (q.v.) by an environment, other conceptions of ‘intention’ or ‘purpose’ being rejected or treated as at best secondary, the predominant emphasis being always on (observable) effect: behaviour. In the human sciences, and in many socially applied (and far from neutral) fields such as COMMUNICATIONS (q.v.) and advertising (which developed from its general sense of ‘notification’, from Cl5, to a system of organized influence on CONSUMER (q.v.) behaviour, especially from lC19), the relatively neutral physical senses of stimulus and response have been developed into a reductive system of ‘controlled’ behaviour as a summary of all significant human activity. (Controlled is interesting because of the overlap between conditions of observable experiment – developed from the sense of a system of checks in commercial accounting, from C15 – and conditions of the exercise of restraint or power over others, also from C15. The two modern senses are held as separate, but there has been some practical transfer between them.) The most important effect is the description of certain ‘intentional’ and ‘purposive’ human practices and systems as if they were ‘natural’ or ‘objective’ stimuli, to which responses can be graded as ‘normal’ or ‘abnormal’ or ‘deviant’. The sense of ‘autonomous’ or ‘independent’ response (either generally, or in the sense of being outside the terms of a given system) can thus be weakened, with important effects in politics and sociology (cf. ‘deviant groups’, ‘deviant political behaviour’), in psychology (cf. RATIONALIZATION) and in the understanding of intelligence or of language (language behaviour), where there is now considerable argument between an extended sense of behaviourist explanations and explanations based on such terms as generative or CREATIVE (q.v.).

Apart from these particular and central controversies, it remains significant that a term for public conduct should have developed into our most widely used and most apparently neutral term for all kinds of activity.

BOURGEOIS (#ulink_066fbfe4-ad56-555f-9b8c-5317721d4356)

Bourgeois is a very difficult word to use in English: first, because although quite widely used it is still evidently a French word, the earlier Anglicization to burgess, from oF burgeis and mE burgeis, burges, borges – inhabitant of a borough, having remained fixed in its original limited meaning; secondly, because it is especially associated with Marxist argument, which can attract hostility or dismissal (and it is relevant here that in this context bourgeois cannot properly be translated by the more familiar English adjective middle-class); thirdly, because it has been extended, especially in English in the last twenty years, partly from this Marxist sense but mainly from much earlier French senses, to a general and often vague term of social contempt. To understand this range it is necessary to follow the development of the word in French, and to note a particular difficulty in the translation, into both French and English, of the German bürgerlich.

Under the feudal regime in France bourgeois was a juridical category in society, defined by such conditions as length of residence. The essential definition was that of the solid citizen whose mode of life was at once stable and solvent. The earliest adverse meanings come from a higher social order: an aristocratic contempt for the mediocrity of the bourgeois which extended, especially in C18, into a philosophical and intellectual contempt for the limited if stable life and ideas of this ‘middle’ class (there was a comparable English C17 and C18 use of citizen and its abbreviation cit). There was a steady association of the bourgeois with trade, but to succeed as a bourgeois, and to live bourgeoisement, was typically to retire and live on invested income. A bourgeois house was one in which no trade or profession (lawyers and doctors were later excepted) could be carried on.

The steady growth in size and importance of this bourgeois class in the centuries of expanding trade had major consequences in political thought, which in turn had important complicating effects on the word. A new concept of SOCIETY (q.v.) was expressed and translated in English, especially in C18, as civil society, but the equivalents for this adjective were and in some senses still are the French bourgeois and the German bürgerlich. In later English usage these came to be translated as bourgeois in the more specific C19 sense, often leading to confusion.

Before the specific Marxist sense, bourgeois became a term of contempt, but also of respect from below. The migrant labourer or soldier saw the established bourgeois as his opposite; workers saw the capitalized bourgeois as an employer. The social dimension of the later use was thus fully established by lC18, although the essentially different aristocratic or philosophical contempt was still an active sense.

The definition of bourgeois society was a central concept in Marx, yet especially in some of his early work the term is ambiguous, since in relation to Hegel for whom civil (bürgerlich) society was an important term to be distinguished from STATE (q.v.) Marx used, and in the end amalgamated, the earlier and the later meanings. Marx’s new sense of bourgeois society followed earlier historical usage, from established and solvent burgesses to a growing class of traders, entrepreneurs and employers. His attack on what he called bourgeois political theory (the theory of civil society) was based on what he saw as its falsely universal concepts and institutions, which were in fact the concepts and institutions of a specifically bourgeois society: that is, a society in which the bourgeoisie (the class name was now much more significant) had become or was becoming dominant. Different stages of bourgeois society led to different stages of the CAPITALIST (q.v.) mode of economic production, or, as it was later more strictly put, different stages of the capitalist mode of production led to different stages of bourgeois society and hence bourgeois thought, bourgeois feeling, bourgeois ideology, bourgeois art. In Marx’s sense the word has passed into universal usage. But it is often difficult to separate it, in some respects, from the residual aristocratic and philosophical contempt, and from a later form especially common among unestablished artists, writers and thinkers, who might not and often do not share Marx’s central definition, but who sustain the older sense of hostility towards the (mediocre) established and respectable.

The complexity of the word is then evident. There is a problem even in the strict Marxist usage, in that the same word, bourgeois, is used to describe historically distinct periods and phases of social and cultural development. In some contexts, especially, this is bound to be confusing: the bourgeois ideology of settled independent citizens is clearly not the same as the bourgeois ideology of the highly mobile agents of a para-national corporation. The distinction of petit-bourgeois is an attempt to preserve some of the earlier historical characteristics, but is also used for a specific category within a more complex and mobile society. There are also problems in the relation between bourgeois and capitalist, which are often used indistinguishably but which in Marx are primarily distinguishable as social and economic terms. There is a specific difficulty in the description of non-urban capitalists (e.g. agrarian capitalist employers) as bourgeois, with its residual urban sense, though the social relations they institute are clearly bourgeois in the developed C19 sense. There is also difficulty in the relation between descriptions of bourgeois society and the bourgeois or bourgeoisie as a class. A bourgeois society, according to Marx, is one in which the bourgeois class is dominant, but there can then be difficulties of usage, associated with some of the most intense controversies of analysis, when the same word is used for a whole society in which one class is dominant (but in which, necessarily, there are other classes) and for a specific class within that whole society. The difficulty is especially noticeable in uses of bourgeois as an adjective describing some practice which is not itself defined by the manifest social and economic content of bourgeois.