По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

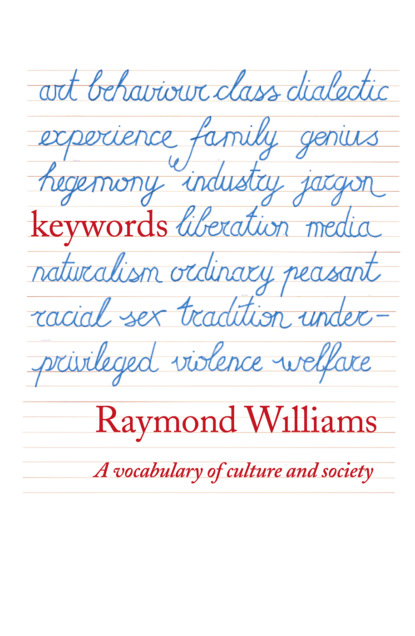

Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It is thus not surprising that there is resistance to the use of the word in English, but it has also to be said that for its precise uses in Marxist and other historical and political argument there is no real English alternative. The translation middle-class serves most of the pre-C19 meanings, in pointing to the same kinds of people, and their ways of life and opinions, as were then indicated by bourgeois, and had been indicated by citizen and cit and civil; general uses of citizen and cit were common until lC18 but less common after the emergence of middle-class in lC18. But middle-class (see CLASS), though a modern term, is based on an older threefold division of society – upper, middle and lower – which has most significance in feudal and immediately post-feudal society and which, in the sense of the later uses, would have little or no relevance as a description of a developed or fully formed bourgeois society. A ruling class, which is the socialist sense of bourgeois in the context of historical description of a developed capitalist society, is not easily or clearly represented by the essentially different middle class. For this reason, especially in this context and in spite of the difficulties, bourgeois will continue to have to be used.

See CAPITALISM, CIVILIZATION, CLASS, SOCIETY

BUREAUCRACY (#ulink_af491971-1ba9-5db4-a023-d73cc8f131a1)

Bureaucracy appears in English from mC19. Carlyle in Latter-day Pamphlets (1850) wrote of ‘the Continental nuisance called “Bureaucracy”’, and Mill in 1848 wrote of the inexpediency of concentrating all the power of organized action ‘in a dominant bureaucracy’. In 1818, using an earlier form, Lady Morgan had written of the ‘Bureaucratie or office tyranny, by which Ireland had been so long governed’. The word was taken from fw bureaucratie, F, rw bureau – writing-desk and then office. The original meaning of bureau was the baize used to cover desks. The English use of bureau as office dates from eC18; it became more common in American use, especially with reference to foreign branches, the French influence being predominant. The increasing scale of commercial organization, with a corresponding increase in government intervention and legal controls, and with the increasing importance of organized and professional central government, produced the political facts to which the new term pointed. But there was then considerable variation in their evaluation. In English and North American usage the foreign term, bureaucracy, was used to indicate the rigidity or excessive power of public administration, while such terms as public service or civil service were used to indicate impartiality and selfless professionalism. In German Bureaukratie often had the more favourable meaning, as in Schmoller (‘the only neutral element’, apart from the monarchy, ‘in the class war’), and was given a further sense of legally established rationality by Weber. The variation of terms can still confuse the variations of evaluation, and indeed the distinctions between often diverse political systems which ‘a body of public servants’ or a bureaucracy can serve. Beyond this, however, there has been a more general use of bureaucracy to indicate, unfavourably, not merely the class of officials but certain types of centralized social order, of a modern organized kind, as distinct not only from older aristocratic societies but from popular DEMOCRACY (q.v.). This has been important in socialist thought, where the concept of the ‘public interest’ is especially exposed to the variation between ‘public service’ and ‘bureaucracy’.

In more local ways, bureaucracy is used to refer to the complicated formalities of official procedures, what the Daily News in 1871 described as ‘the Ministry … with all its routine of tape, wax, seals, and bureauism’. There is again an area of uncertainty between two kinds of reference, as can be seen by the coinage of more neutral phrases such as ‘business methods’ and ‘office organization’ for commercial use, bureaucracy being often reserved for similar or identical procedures in government.

See DEMOCRACY, MANAGEMENT

C (#ulink_2227ebe6-9491-528a-9a41-7974ab5c671f)

CAPITALISM (#ulink_2227ebe6-9491-528a-9a41-7974ab5c671f)

Capitalism as a word describing a particular economic system began to appear in English from eC19, and almost simultaneously in French and German. Capitalist as a noun is a little older; Arthur Young used it, in his journal of Travels in France (1792), but relatively loosely: ‘moneyed men, or capitalists’. Coleridge used it in the developed sense – ‘capitalists … having labour at demand’ – in Tabletalk (1823). Thomas Hodgskin, in Labour Defended against the Claims of Capital (1825) wrote: ‘all the capitalists of Europe, with all their circulating capital, cannot of themselves supply a single week’s food and clothing’, and again: ‘betwixt him who produces food and him who produces clothing, betwixt him who makes instruments and him who uses them, in steps the capitalist, who neither makes nor uses them and appropriates to himself the produce of both’. This is clearly the description of an economic system.

The economic sense of capital had been present in English from C17 and in a fully developed form from C18. Chambers Cyclopaedia (1727–51) has ‘power given by Parliament to the South-Sea company to increase their capital’ and definition of ‘circulating capital’ is in Adam Smith (1776). The word had acquired this specialized meaning from its general sense of ‘head’ or ‘chief’: fw capital, F, capitalist L, rw caput, L – head. There were many derived specialist meanings; the economic meaning developed from a shortening of the phrase ‘capital stock’ – a material holding or monetary fund. In classical economics the functions of capital, and of various kinds of capital, were described and defined.

Capitalism represents a development of meaning in that it has been increasingly used to indicate a particular and historical economic system rather than any economic system as such. Capital and at first capitalist were technical terms in any economic system. The later (eC19) uses of capitalist moved towards specific functions in a particular stage of historical development; it is this use that crystallized in capitalism. There was a sense of the capitalist as the useless but controlling intermediary between producers, or as the employer of labour, or, finally, as the owner of the means of production. This involved, eventually, and especially in Marx, a distinction of capital as a formal economic category from capitalism as a particular form of centralized ownership of the means of production, carrying with it the system of wage-labour. Capitalism in this sense is a product of a developing bourgeois society; there are early kinds of capitalist production but capitalism as a system – what Marx calls ‘the capitalist era’ – dates only from C16 and did not reach the stage of industrial capitalism until lC18 and eC19.

There has been immense controversy about the details of this description, and of course about the merits and workings of the system itself, but from eC20, in most languages, capitalism has had this sense of a distinct economic system, which can be contrasted with other systems. As a term capitalism does not seem to be earlier than the 1880s, when it began to be used in German socialist writing and was extended to other non-socialist writing. Its first English and French uses seem to date only from the first years of C20. In mC20, in reaction against socialist argument, the words capitalism and capitalist have often been deliberately replaced by defenders of the system by such phrases as ‘private enterprise’ and ‘free enterprise’.

These terms, recalling some of the conditions of early capitalism, are applied without apparent hesitation to very large or para-national ‘public’ corporations, or to an economic system controlled by them. At other times, however, capitalism is defended under its own now common name. There has also developed a use of post-capitalist and post-capitalism, to describe modifications of the system such as the supposed transfer of control from shareholders to professional management, or the coexistence of certain NATIONALIZED (q.v.) or ‘state-owned’ industries. The plausibility of these descriptions depends on the definition of capitalism which they are selected to modify. Though they evidently modify certain kinds of capitalism, in relation to its central sense they are marginal. A new phrase, state-capitalism, has been widely used in mC20, with precedents from eC20, to describe forms of state ownership in which the original conditions of the definition – centralized ownership of the means of production, leading to a system of wage-labour – have not really changed.

It is also necessary to note an extension of the adjective capitalist to describe the whole society, or features of the society, in which a capitalist economic system predominates. There is considerable overlap and occasional confusion here between capitalist and BOURGEOIS (q.v.). In strict Marxist usage capitalist is a description of a mode of production and bourgeois a description of a type of society. It is in controversy about the relations between a mode of production and a type of society that the conditions for overlap of meaning occur.

See BOURGEOIS, INDUSTRY, SOCIETY

CAREER (#ulink_1a3626d6-db4c-5420-bce5-7ecf457263e0)

Career is now so regularly used to describe a person’s progress in life, or, by derivation from this, his profession or vocation that it is difficult to remember, in the same context, its original meanings of a racecourse and a gallop – though in some contexts, as in the phrase ‘careering about’, these survive.

Career appeared in English from eC16, from fw carrière, F – racecourse, rw carraria, L – carriage road, from carrus, L – wagon. It was used from C16 for racecourse, gallop, and by extension any rapid or uninterrupted activity. Though sometimes applied neutrally, as of the course of the sun, it had a predominant C17 and C18 sense not only of rapid but of unrestrained activity. It is not easy to be certain of the change of implication between, for example, a use in 1767 – ‘a … beauty … in the career of her conquests’ – and Macaulay’s use in 1848 – ‘in the full career of success’. But it is probable that it was from eC19 that the use without derogatory implication began, especially with reference to diplomats and statesmen. By mC19 the word was becoming common to indicate progress in a vocation and then the vocation itself.

At this point, and especially in the course of C20, career becomes inseparable from a difficult group of words of which WORK, LABOUR (qq.v.) and especially job are prominent examples. Career is still used in the abstract spectacular sense of politicians and entertainers, but more generally it is applied, with some conscious and unconscious class distinction, to work or a job which contains some implicit promise of progress. It has been most widely used for jobs with explicit internal development – ‘a career in the Civil Service’ – but it has since been extended to any favourable or desired or flattered occupation – ‘a career in coalmining’. Career now usually implies continuity if not necessarily promotion or advancement, yet the distinction between a career and a job only partly depends on this and is often associated also with class distinctions between different kinds of work. On the other hand, the extension of the term, as in ‘careers advice’, sometimes cancels these associations, and there has been an American description of ‘semi-skilled workers’ as having a ‘flat career trajectory’.

It is interesting that something like the original metaphor, with its derogatory C17 or C18 sense, has reappeared in descriptions of some areas of work and promotion as the rat-race. But of course the derogatory sense is directly present in the derived words careerism and careerist, which are held carefully separate from the positive implications of career. Careerist is recorded from 1917, and careerism from 1933; the early uses refer to parliamentary politics.

See LABOUR, WORK

CHARITY (#ulink_03e8696f-45bc-53d6-ba70-09edf9ec2ee5)

Charity came into English, in C12, from fw charité, oF, caritas, L, rw cants – clear. Forms of the Latin word had taken on the sense of clearness of price as well as affection (an association repeated and continued in clear itself, from oE onwards). But the predominant use of charity was in the context of the Bible. (Greek agape had been distinguished into dilectio and caritas in the Vulgate, and Wyclif translated these as love and charity. Tyndale rendered caritas as love, and in the fierce doctrinal disputes of C16 this translation was criticized, the ecclesiastical charity being preferred in the Bishop’s Bible and then in the Authorized Version. Love was one of the key terms of the C19 Revised Version.) Charity was then Christian love, between man and God, and between men and their neighbours. The sense of benevolence to neighbours, and specifically of gifts to the needy, is equally early, but was at first directly related to the sense of Christian love, as in the Pauline use: ‘though I bestow all my goods to feed the poor … and have not charity, it profiteth me nothing’ (1 Corinthians 13) where the act without the feeling is seen as null. Nevertheless, charity in the predominant sense of help to the needy came through steadily; it is probably already dominant in C16 and is used with a new sense of abstraction from lC17 and eC18. A charity as an institution was established by lC17. These senses have of course persisted.

But there is another movement in the word. Charity begins at home was already a popular saying in eC17 and has precedents from C14. More significant is cold as charity, which is an interesting reversal of what is probably the original use in Matthew 24:12, where the prophecy of ‘wars and rumours of wars’ and of the rise of ‘many false prophets’ is capped by this: ‘because iniquity shall abound, the love of many shall wax cold’. This is the most general Christian sense. Earlier translations (e.g. Rhemish, 1582) had used: ‘charity of many shall wax cold’. Browne (1642) wrote of ‘the general complaint of these times … that Charity grows cold’. By lC18 the sense had been reversed. It was not the sense of a drying-up or freezing of love or benevolence; it was the more interesting sense of what the charitable act feels like to the recipient from prolonged experience of the habits and manners of most charitable institutions. This sense has remained very important, and some people still say that they will not ‘take charity’, even from public funds to which they have themselves contributed. It is true that this includes an independent feeling against being helped by others, but the odium which has gathered around charity in this context comes from feelings of wounded self-respect and dignity which belong, historically, to the interaction of charity and of class-feelings, on both sides of the act. Critical marks of this interaction are the specialization of charity to the deserving poor (not neighbourly love, but reward for approved social conduct) and the calculation in bourgeois political economy summed up by Jevons (1878): ‘all that the political economist insists upon is that charity shall be really charity, and shall not injure those whom it is intended to aid’ (not the relief of need, but its selective use to preserve the incentive to wage-labour). It is not surprising that the word which was once the most general expression of love and care for others has become (except in special contexts, following the surviving legal definition of benevolent institutions) so compromised that modern governments have to advertise welfare benefits (and with a wealth of social history in the distinction) as ‘not a charity but a right’.

CITY (#ulink_e3140e30-90a6-53b0-9ba4-3629966eeaba)

City has existed in English since C13, but its distinctive modern use to indicate a large or very large town, and its consequent use to distinguish urban areas from rural areas or country, date from C16. The later indication and distinction are obviously related to the increasing importance of urban life from C16 onwards, but until C19 this was often specialized to the capital city, London. The more general use corresponds to the rapid development of urban living during the Industrial Revolution, which made England by mC19 the first society in the history of the world in which a majority of the population lived in towns.

City is derived from fw cité, oF, rw civitas, L. But civitas was not city in the modern sense; that was urbs, L. Civitas was the general noun derived from civis, L – citizen, which is nearer our modern sense of a ‘national’. Civitas was then the body of citizens rather than a particular settlement or type of settlement. It was so applied by Roman writers to the tribes of Gaul. In a long and complicated development civitas and the words derived from it became specialized to the chief town of such a state, and in ecclesiastical use to the cathedral town. The earlier English words had been borough, fw burh, oE and town, fw tun, oE. Town developed from its original sense of an enclosure or yard to a group of buildings in such an enclosure (as which it survives in some modern village and village-division names) to the beginnings of its modern sense in C13. Borough and city became often interchangeable, and there are various legal distinctions between them in different periods and types of medieval and post-medieval government. One such distinction of city, from C16, was the presence of a cathedral, and this is still residually though now wrongly asserted. When city began to be distinguished from town in terms of size, mainly from C19 but with precedents in relation to the predominance of London from C16, each was still administratively a borough, and this word became specialized to a form of local government or administration. From C13 city became in any case a more dignifying word than town; it was often thus used of Biblical villages, or to indicate an ideal or significant settlement. More generally, by C16 city was in regular use for London, and in C17 city and country contrasts were very common. City in the specialized sense of a financial and commercial centre, derived from actual location in the City of London, was widely used from eC18, when this financial and commercial activity notably expanded.

The city as a really distinctive order of settlement, implying a whole different way of life, is not fully established, with its modern implications, until eC19, though the idea has a very long history, from Renaissance and even Classical thought. The modern emphasis can be traced in the word, in the increasing abstraction of city as an adjective from particular places or particular administrative forms, and in the increasing generalization of descriptions of large-scale modern urban living. The modern city of millions of inhabitants is thus generally if indefinitely distinguished from several kinds of city – cf. cathedral city, university city, provincial city – characteristic of earlier periods and types of settlement. At the same time the modern city has been subdivided, as in the increasing contemporary use of inner city, a term made necessary by the changing status of suburb. This had been, from C17, an outer and inferior area, and the sense survives in some uses of suburban to indicate narrowness. But from lC19 there was a class shift in areas of preference; the suburbs attracted residents and the inner city was then often left to offices, shops and the poor.

See COUNTRY, CIVILIZATION

CIVILIZATION (#ulink_0225b51e-4009-5d03-9c44-aa0ddbef1e85)

Civilization is now generally used to describe an achieved state or condition of organized social life. Like CULTURE (q.v.) with which it has had a long and still difficult interaction, it referred originally to a process, and in some contexts this sense still survives.

Civilization was preceded in English by civilize, which appeared in eC17, from C16 civiliser, F, fw civilizare, mL – to make a criminal matter into a civil matter, and thence, by extension, to bring within a form of social organization. The rw is civil from civilis, L – of or belonging to citizens, from civis, L – citizen. Civil was thus used in English from C14, and by C16 had acquired the extended senses of orderly and educated. Hooker in 1594 wrote of ‘Civil Society’ – a phrase that was to become central in C17 and especially C18 – but the main development towards description of an ordered society was civility, fw civilitas, mL – community. Civility was often used in C17 and C18 where we would now expect civilization, and as late as 1772 Boswell, visiting Johnson, ‘found him busy, preparing a fourth edition of his folio Dictionary … He would not admit civilization, but only civility. With great deference to him, I thought civilization, from to civilize, better in the sense opposed to barbarity, than civility.’ Boswell had correctly identified the main use that was coming through, which emphasized not so much a process as a state of social order and refinement, especially in conscious historical or cultural contrast with barbarism. Civilization appeared in Ash’s dictionary of 1775, to indicate both the state and the process. By lC18 and then very markedly in C19 it became common.

In one way the new sense of civilization, from lC18, is a specific combination of the ideas of a process and an achieved condition. It has behind it the general spirit of the Enlightenment, with its emphasis on secular and progressive human self-development. Civilization expressed this sense of historical process, but also celebrated the associated sense of modernity: an achieved condition of refinement and order. In the Romantic reaction against these claims for civilization, alternative words were developed to express other kinds of human development and other criteria for human well-being, notably CULTURE (q.v.). In lC18 the association of civilization with refinement of manners was normal in both English and French. Burke wrote in Reflections on the French Revolution: ‘our manners, our civilization, and all the good things which are connected with manners, and with civilization’. Here the terms seem almost synonymous, though we must note that manners has a wider reference than in ordinary modern usage. From eC19 the development of civilization towards its modern meaning, in which as much emphasis is put on social order and on ordered knowledge (later, SCIENCE (q.v.)) as on refinement of manners and behaviour, is on the whole earlier in French than in English. But there was a decisive moment in English in the 1830s, when Mill, in his essay on Coleridge, wrote:

Take for instance the question how far mankind has gained by civilization. One observer is forcibly struck by the multiplication of physical comforts; the advancement and diffusion of knowledge; the decay of superstition; the facilities of mutual intercourse; the softening of manners; the decline of war and personal conflict; the progressive limitation of the tyranny of the strong over the weak; the great works accomplished throughout the globe by the co-operation of multitudes …

This is Mill’s range of positive examples of civilization, and it is a fully modern range. He went on to describe negative effects: loss of independence, the creation of artificial wants, monotony, narrow mechanical understanding, inequality and hopeless poverty. The contrast made by Coleridge and others was between civilization and culture or cultivation:

The permanent distinction and the occasional contrast between cultivation and civilization … The permanency of the nation … and its progressiveness and personal freedom … depend on a continuing and progressive civilization. But civilization is itself but a mixed good, if not far more a corrupting influence, the hectic of disease, not the bloom of health, and a nation so distinguished more fitly to be called a varnished than a polished people, where this civilization is not grounded in cultivation, in the harmonious development of those qualities and faculties that characterize our humanity. (On the Constitution of Church and State, V)

Coleridge was evidently aware in this passage of the association of civilization with the polishing of manners; that is the point of the remark about varnish, and the distinction recalls the curious overlap, in C18 English and French, between polished and polite, which have the same root. But the description of civilization as a ‘mixed good’, like Mill’s more elaborated description of its positive and negative effects, marks the point at which the word has come to stand for a whole modern social process. From this time on this sense was dominant, whether the effects were reckoned as good, bad or mixed.

Yet it was still primarily seen as a general and indeed universal process. There was a critical moment when civilization was used in the plural. This is later with civilizations than with cultures; its first clear use is in French (Ballanche) in 1819. It is preceded in English by implicit uses to refer to an earlier civilization, but it is not common anywhere until the 1860s.

In modern English civilization still refers to a general condition or state, and is still contrasted with savagery or barbarism. But the relativism inherent in comparative studies, and reflected in the use of civilizations, has affected this main sense, and the word now regularly attracts some defining adjective: Western civilization, modern civilization, industrial civilization, scientific and technological civilization. As such it has come to be a relatively neutral form for any achieved social order or way of life, and in this sense has a complicated and much disputed relation with the modern social sense of culture. Yet its sense of an achieved state is still sufficiently strong for it to retain some normative quality; in this sense civilization, a civilized way of life, the conditions of civilized society may be seen as capable of being lost as well as gained.

See CITY, CULTURE, DEVELOPMENT, MODERN, SOCIETY, WESTERN

CLASS (#ulink_df2be4f0-15d8-5ed4-a21c-dc99d20d1fe4)

Class is an obviously difficult word, both in its range of meanings and in its complexity in that particular meaning where it describes a social division. The Latin word classis, a division according to property of the people of Rome, came into English in lC16 in its Latin form, with a plural classes or classics. There is a lC16 use (King, 1594) which sounds almost modern: ‘all the classics and ranks of vanitie’. But classis was primarily used in explicit reference to Roman history, and was then extended, first as a term in church organization (‘assemblies are either classes or synods’, 1593) and later as a general term for a division or group (‘the classis of Plants’, 1664). It is worth noting that the derived Latin word classicus, coming into English in eC17 as classic from fw classique, F, had social implications before it took on its general meaning of a standard authority and then its particular meaning of belonging to Greek and Roman antiquity (now usually distinguished in the form classical, which at first alternated with classic). Gellius wrote: ‘classicus … scriptor, non proletarius’. But the form class, coming into English in Cl7, acquired a special association with education. Blount, glossing classe in 1656, included the still primarily Roman sense of ‘an order or distribution of people according to their several Degrees’ but added: ‘in Schools (wherein this word is most used) a Form or Lecture restrained to a certain company of Scholars’ – a use which has remained common in education. The development of classic and classical was strongly affected by this association with authoritative works for study.

From lC17 the use of class as a general word for a group or division became more and more common. What is then most difficult is that class came to be used in this way about people as well as about plants and animals, but without social implications of the modern kind. (Cf. Steele, 1709: ‘this Class of modern Wits’.) Development of class in its modern social sense, with relatively fixed names for particular classes (lower class, middle class, upper class, working class and so on), belongs essentially to the period between 1770 and 1840, which is also the period of the Industrial Revolution and its decisive reorganization of society. At the extremes it is not difficult to distinguish between (i) class as a general term for any grouping and (ii) class as a would-be specific description of a social formation. There is no difficulty in distinguishing between Steele’s ‘Class of modern Wits’ and, say, the Declaration of the Birmingham Political Union (1830) ‘that the rights and interests of the middle and lower classes of the people are not efficiently represented in the Commons House of Parliament’. But in the crucial period of transition, and indeed for some time before it, there is real difficulty in being sure whether a particular use is sense (i) or sense (ii). The earliest use that I know, which might be read in a modern sense, is Defoe’s ‘’tis plain the clearness of wages forms our people into more classes than other nations can show’ (Review, 14 April 1705). But this, even in an economic context, is far from certain. There must also be some doubt about Hanway’s title of 1772: ‘Observations on the Causes of the Dissoluteness which reigns among the lower classes of the people’. We can read this, as indeed we would read Defoe, in a strictly social sense, but there is enough overlap between sense (i) and sense (ii) to make us pause. The crucial context of this development is the alternative vocabulary for social divisions, and it is a fact that until lC18, and residually well into C19 and even C20, the most common words were rank and order, while estate and degree were still more common than class. Estate, degree and order had been widely used to describe social position from medieval times. Rank had been common from lC16. In virtually all contexts where we would now say class these other words were standard, and lower order and lower orders became especially common in C18.

The essential history of the introduction of class, as a word which would supersede older names for social divisions, relates to the increasing consciousness that social position is made rather than merely inherited. All the older words, with their essential metaphors of standing, stepping and arranging in rows, belong to a society in which position was determined by birth. Individual mobility could be seen as movement from one estate, degree, order or rank to another. What was changing consciousness was not only increased individual mobility, which could be largely contained within the older terms, but the new sense of a SOCIETY (q.v.) or a particular social system which actually created social divisions, including new kinds of divisions. This is quite explicit in one of the first clear uses, that of Madison in The Federalist (USA, c. 1787): moneyed and manufacturing interests ‘grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views’. Under the pressure of this awareness, greatly sharpened by the economic changes of the Industrial Revolution and the political conflicts of the American and French revolutions, the new vocabulary of class began to take over. But it was a slow and uneven process, not only because of the residual familiarity of the older words, and not only because conservative thinkers continued, as a matter of principle, to avoid class wherever they could and to prefer the older (and later some newer) terms. It was slow and uneven, and has remained difficult, mainly because of the inevitable overlap with the use of class not as a specific social division but as a generally available and often ad hoc term of grouping.

With this said, we can trace the formation of the newly specific class vocabulary. Lower classes was used in 1772, and lowest classes and lowest class were common from the 1790s. These carry some of the marks of the transition, but do not complete it. More interesting because less dependent on an old general sense, in which the lower classes would be not very different from the COMMON (q.v.) people, is the new and increasingly self-conscious and self-used description of the middle classes. This has precedents in ‘men of a middle condition’ (1716), ‘the middle Station of life’ (Defoe, 1719), ‘the Middling People of England … generally Good-natured and Stout-hearted’ (1718), ‘the middling and lower classes’ (1789). Gisborne in 1795 wrote an ‘Enquiry into the Duties of Men in the Higher Rank and Middle Classes of Society in Great Britain’. Hannah More in 1796 wrote of the ‘middling classes’. The ‘burden of taxation’ rested heavily ‘on the middle classes’ in 1809 (Monthly Repository, 501), and in 1812 there was reference to ‘such of the Middle Class of Society who have fallen upon evil days’ (Examiner, August). Rank was still used at least as often, as in James Mill (1820): ‘the class which is universally described as both the most wise and the most virtuous part of the community, the middle rank’ (Essay on Government), but here class has already taken on a general social sense, used on its own. The swell of self-congratulatory description reached a temporary climax in Brougham’s speech of 1831: ‘by the people, I mean the middle classes, the wealth and intelligence of the country, the glory of the British name’.

There is a continuing curiosity in this development. Middle belongs to a disposition between lower and higher, in fact as an insertion between an increasingly insupportable high and low. Higher classes was used by Burke (Thoughts on French Affairs) in 1791, and upper classes is recorded from the 1820s. In this model an old hierarchical division is still obvious; the middle class is a self-conscious interposition between persons of rank and the common people. This was always, by definition, indeterminate: this is one of the reasons why the grouping word class rather than the specific word rank eventually came through. But clearly in Brougham, and very often since, the upper or higher part of the model virtually disappears, or, rather, awareness of a higher class is assigned to a different dimension, that of a residual and respected but essentially displaced aristocracy.

This is the ground for the next complication. In the fierce argument about political, social and economic rights, between the 1790s and the 1830s, class was used in another model, with a simple distinction of the productive or useful classes (a potent term against the aristocracy). In the widely read translation of Volney’s The Ruins, or A Survey of the Revolutions of Empires (2 parts, 1795) there was a dialogue between those who by ‘useful labours contribute to the support and maintenance of society’ (the majority of the people, ‘labourers, artisans, tradesmen and every profession useful to society’, hence called People) and a Privileged class (‘priests, courtiers, public accountants, commanders of troops, in short, the civil, military or religious agents of government’). This is a description in French terms of the people against an aristocratic government, but it was widely adopted in English terms, with one particular result which corresponds to the actual political situation of the reform movement between the 1790s and the 1830s: both the self-conscious middle classes and the quite different people who by the end of this period would describe themselves as the working classes adopted the descriptions useful or productive classes, in distinction from and in opposition to the privileged or the idle. This use, which of course sorts oddly with the other model of lower, middle and higher, has remained both important and confusing.

For it was by transfer from the sense of useful or productive that the working classes were first named. There is considerable overlap in this: cf. ‘middle and industrious classes’ (Monthly Magazine, 1797) and ‘poor and working classes’ (Owen, 1813) – the latter probably the first English use of working classes but still very general. In 1818 Owen published Two Memorials on Behalf of the Working Classes, and in the same year The Gorgon (28 November) used working classes in the specific and unmistakable context of relations between ‘workmen’ and ‘their employers’. The use then developed rapidly, and by 1831 the National Union of the Working Classes identified not so much privilege as the ‘laws … made to protect … property or capital’ as their enemy. (They distinguished such laws from those that had not been made to protect INDUSTRY (q.v.), still in its old sense of applied labour.) In the Poor Man’s Guardian (19 October 1833), O’Brien wrote of establishing for ‘the productive classes a complete dominion over the fruits of their own industry’ and went on to describe such a change as ‘contemplated by the working classes’; the two terms, in this context, are interchangeable. There are complications in phrases like the labouring classes and the operative classes, which seem designed to separate one group of the useful classes from another, to correspond with the distinction between workmen and employers, or men and masters: a distinction that was economically inevitable and that was politically active from the 1830s at latest. The term working classes, originally assigned by others, was eventually taken over and used as proudly as middle classes had been: ‘the working classes have created all wealth’ (Rules of Ripponden Co-operative Society; cit. J. H. Priestley, History of RCS; dating from 1833 or 1839).

By the 1840s, then, middle classes and working classes were common terms. The former became singular first; the latter is singular from the 1840s but still today alternates between singular and plural forms, often with ideological significance, the singular being normal in socialist uses, the plural more common in conservative descriptions. But the most significant effect of this complicated history was that there were now two common terms, increasingly used for comparison, distinction or contrast, which had been formed within quite different models. On the one hand middle implied hierarchy and therefore implied lower class: not only theoretically but in repeated practice. On the other hand working implied productive or useful activity, which would leave all who were not working class unproductive and useless (easy enough for an aristocracy, but hardly accepted by a productive middle class). To this day this confusion reverberates. As early as 1844 Cockburn referred to ‘what are termed the working-classes, as if the only workers were those who wrought with their hands’. Yet working man or workman had a persistent reference to manual labour. In an Act of 1875 this was given legal definition: ‘the expression workman … means any person who, being a labourer, servant in husbandry, journeyman, artificer, handicraftsman, miner, or otherwise engaged in manual labour … has entered into or works under a contract with an employer’. The association of workman and working class was thus very strong, but it will be noted that the definition includes contract with an employer as well as manual work. An Act of 1890 stated: ‘the provisions of section eleven of the Housing of the Working Classes Act, 1885 … shall have effect as if the expression working classes included all classes of persons who earn their livelihood by wages or salaries’. This permitted a distinction from those whose livelihood depended on fees (professional class), profits (trading class) or property (independent). Yet, especially with the development of clerical and service occupations, there was a critical ambiguity about the class position of those who worked for a salary or even a wage and yet did not do manual labour. (Salary as fixed payment dates from C14; wages and salaries is still a normal C19 phrase; in 1868, however, ‘a manager of a bank or railway – even an overseer or a clerk in a manufactory – is said to draw a salary’, and the attempted class distinction between salaries and wages is evident; by eC20 the salariat was being distinguished from the proletariat.) Here again, at a critical point, the effect of two models of class is evident. The middle class, with which the earners of salaries normally aligned themselves, is an expression of relative social position and thus of social distinction. The working class, specialized from the different notion of the useful or productive classes, is an expression of economic relationships. Thus the two common modern class terms rest on different models, and the position of those who are conscious of relative social position and thus of social distinction, and yet, within an economic relationship, sell and are dependent on their labour, is the point of critical overlap between the models and the terms. It is absurd to conclude that only the working classes WORK (q.v.), but if those who work in other than ‘manual’ labour describe themselves in terms of relative social position (middle class) the confusion is inevitable. One side effect of this difficulty was a further elaboration of classing itself (the period from lC18 to lC19 is rich in these derived words: classify, classifier, classification). From the 1860s the middle class began to be divided into lower and upper sections, and later the working class was to be divided into skilled, semi-skilled and labouring. Various other systems of classification succeeded these, notably socio-economic group, which must be seen as an attempt to marry the two models of class, and STATUS (q.v.).

It is necessary, finally, to consider the variations of class as an abstract idea. In one of the earliest uses of the singular social term, in Crabbe’s