По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

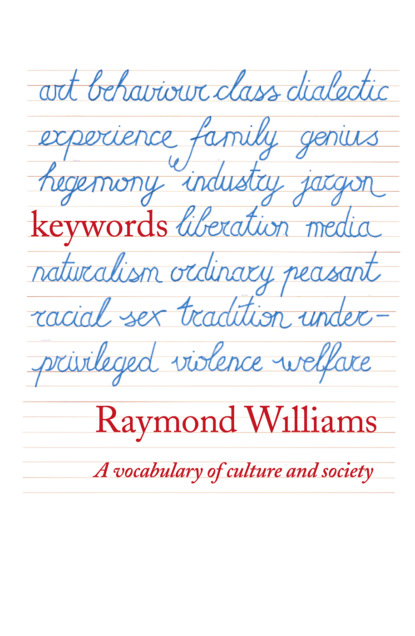

Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

COUNTRY (#ulink_bef49872-e561-5cc6-ac32-36779a08e23a)

Country has two different meanings in modern English: broadly, a native land and the rural or agricultural parts of it.

The word is historically very curious, since it derives from the feminine adjective contrata, mL, rw contra, L – against, in the phrase contrata terra meaning land ‘lying opposite, over against or facing’. In its earliest separate meaning it was a tract of land spread out before an observer. (Cf. the later use of landskip, C16, landscape, C18; in oE landscipe was a region or tract of land; the word was later adopted from Dutch landschap as a term in painting.) Contrata passed into English through oF cuntrée and contrée. It had the sense of native land from C13 and of the distinctly rural areas from eC16. Tyndale (1526) translated part of Mark 5:14 as ‘tolde it in the cyte, and in the countre’.

The widespread specialized use of country as opposed to city began in lC16 with increasing urbanization and especially the growth of the capital, London. It was then that country people and the country house were distinguished. On the other hand countryfied and country bumpkin were C17 metropolitan slang. Countryside, originally a Scottish term to indicate a specific locality, became in C19 a general term to describe not only the rural areas but the whole rural life and economy.

In its general use, for native land, country has more positive associations than either nation or state: cf. ‘doing something for the country’ with ‘doing something for the nation’ or ‘… state’. Country habitually includes the people who live in it, while nation is more abstract and state carries a sense of the structure of power. Indeed country can substitute for people, in political contexts: cf. ‘the country demands’. This is subject to variations of perspective: cf. the English lady who said in 1945: ‘they have elected a socialist government and the country will not stand for it’. In some uses country is regularly distinguished from government: cf. ‘going to the country’ – calling an election. There is also a specialized metropolitan use, as in the postal service, in which all areas outside the capital city are ‘country’.

Countryman carries both political and rural senses, but the latter is stronger and the former is usually extended to fellow-countryman.

See CITY, DIALECT, NATIVE, PEASANT, REGIONAL

CREATIVE (#ulink_55099895-4add-5119-948c-131dd217917d)

Creative in modern English has a general sense of original and innovating, and an associated special sense of productive. It is also used to distinguish certain kinds of work, as in creative writing, the creative arts. It is interesting to see how this now commonplace but still, on reflection, surprising word came to be used, and how this relates to some of its current difficulties.

Create came into English from the stem of the past participle of rw creare, L – make or produce. This inherent relation to the sense of something having been made, and thus to a past event, was exact, for the word was mainly used in the precise context of the original divine creation of the world: creation itself, and creature, have the same root stem. Moreover, within that system of belief, as Augustine insisted, ‘creatura non potest creare’ – the ‘creature’ – who has been created – cannot himself create. This context remained decisive until at least C16, and the extension of the word to indicate present or future making – that is to say a kind of making by men – is part of the major transformation of thought which we now describe as the humanism of the Renaissance. ‘There are two creators,’ wrote Torquato Tasso (1544–95), ‘God and the poet.’ This sense of human creation, specifically in works of the imagination, is the decisive source of the modern meaning. In his Apologie for Poetrie, Philip Sidney (1554–86) saw God as having made Nature but having also made man in his own likeness, giving him the capacity ‘with the force of a divine breath’ to imagine and make things beyond Nature.

Yet use of the word remained difficult, because of the original context. Donne referred to poetry as a ‘counterfeit Creation’, where counterfeit does not have to be taken in its strongest sense of false but where the old sense of art as imitation is certainly present. Several uses of create and creation, in Elizabethan writers, are pejorative:

Or art thou but

A Dagger of the Mind, a false Creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed Brain. (Macbeth)

This is the very coinage of your Brain:

This bodiless Creation extasie

Is very cunning in. (Hamlet)

Are you a God? Would you create me new? (Comedy of Errors)

Translated thus from poor creature to a creator; for now must I create intolerable sort of lies. (Every Man in his Humour)

Indeed the clearest extension of create, without unfavourable implications, was to social rank, given by the authority of the monarch: ‘the King’s Grace created him Duke’ (1495); ‘I create you Companions to our person’ (Cymbeline). This is still not quite human making.

By lC17, however, both create and creation can be found commonly in a modern sense, and during C18 each word acquired a conscious association with ART (q.v.), a word which was itself changing in a complementary direction. It was in relation to this, in Cl8, that creative was coined. Since the word evidently denotes a faculty, it had to wait on general acceptance of create and creation as human actions, without necessary reference to a past divine event. By 1815 Wordsworth could write confidently to the painter Haydon: ‘High is our calling, friend, Creative Art.’ This runs back to the earliest specific reference I have come across: ‘companion of the Muse, Creative Power, Imagination’ (Mallet, 1728). (There is an earlier use of creative in Cudworth, 1678, but in a sentence still partly carrying the older sense: ‘this Divine, miraculous, creative power’.) The decisive development was the conscious and then conventional association of creative with art and thought. By eC19 it was conscious and powerful; by mC19 conventional. Creativity, a general name for the faculty, followed in C20.

This is clearly an important and significant history, and in its emphasis on human capacity the term has become steadily more important. But there is one obvious difficulty. The word puts a necessary stress on originality and innovation, and when we remember the history we can see that these are not trivial claims. Indeed we try to clarify this by distinguishing between innovation and novelty, though novelty has both serious and trivial senses. The difficulty arises when a word once intended, and often still intended, to embody a high and serious claim, becomes so conventional, as a description of certain general kinds of activity, that it is applied to practices for which, in the absence of the convention, nobody would think of making such claims. Thus any imitative or stereotyped literary work can be called, by convention, creative writing, and advertising copywriters officially describe themselves as creative. Given the large elements of simple IDEOLOGICAL and HEGEMONIC (qq.v.) reproduction in most of the written and visual arts, a description of everything of this kind as creative can be confusing and at times seriously misleading. Moreover, to the extent that creative becomes a cant word, it becomes difficult to think clearly about the emphasis which the word was intended to establish: on human making and innovation. The difficulty cannot be separated from the related difficulty of the senses of imagination, which can move towards dreaming and fantasy, with no necessary connection with the specific practices that are called imaginative or creative arts, or, on the other hand, towards extension, innovation and foresight, which not only have practical implications and effects but can be tangible in some creative activities and works. The difficulty is especially apparent when creative is extended, rightly in terms of the historical development, to activities in thought, language and social practice in which the specialized sense of imagination is not a necessary term. Yet such difficulties are inevitable when we realize the necessary magnitude and complexity of the interpretation of human activity which creative now so indispensably embodies.

See ART, IMAGE, FICTION

CRITICISM (#ulink_55410bbe-38b7-5fae-980e-a4f094b474c6)

Criticism has become a very difficult word, because although its predominant general sense is of fault-finding, it has an underlying sense of judgment and a very confusing specialized sense, in relation to art and literature, which depends on assumptions that may now be breaking down. The word came into English in eC17, from critic and critical, mC16, fw criticus, L, kritikos, Gk, rw krités, Gk – a judge. Its predominant early sense was of fault-finding: ‘stand at the marke of criticisme … to bee shot at’ (Dekker, 1607). It was also used for commentary on literature and especially from lC17 for a sense of the act of judging literature and the writing which embodied this. What is most interesting is that the general sense of fault-finding, or at least of negative judgment, has persisted as primary. This has even led to the distinction of appreciation as a softer word for the judgment of literature. But what is significant in the development of criticism, and of critic and critical, is the assumption of judgment as the predominant and even natural response. (Critical has another specialized but important and persistent use, not to describe judgment, but from a specialized use in medicine to refer to a turning point; hence decisive. Crisis itself has of course been extended to any difficulty as well as to any turning point.)

While criticism in its most general sense developed towards censure (itself acquiring from C17 an adverse rather than a neutral implication), criticism in its specialized sense developed towards TASTE (q.v.), cultivation, and later CULTURE (q.v.) and discrimination (itself a split word, with this positive sense for good or informed judgment, but also a strong negative sense of unreasonable exclusion or unfair treatment of some outside group – cf. RACIAL). The formation which underlies the most general development is very difficult to understand because it has taken so strong a hold on our minds. In its earliest period the association is with learned or ‘informed’ ability. It still often tries to retain this sense. But its crucial development, from mC17, depended on the isolation of the reception of impressions: the reader, one might now say, as the CONSUMER (q.v.) of a range of works. Its generalization, within a particular class and profession, depended on the assumptions best represented by taste and cultivation: a form of social development of personal impressions and responses, to the point, where they could be represented as the STANDARDS (q.v.) of judgment. This use seems settled by the time of Kames’s Elements of Criticism (1762). The notion that response was judgment depended, of course, on the social confidence of a class and later a profession. The confidence was variously specified, originally as learning or scholarship, later as cultivation and taste, later still as SENSIBILITY (q.v.). At various stages, forms of this confidence have broken down, and especially in C20 attempts have been made to replace it by objective (cf. SUBJECTIVE) methodologies, providing another kind of basis for judgment. What has not been questioned is the assumption of ‘authoritative judgment’. In its claims to authority it has of course been repeatedly challenged, and critic in the most common form of this specialized sense – as a reviewer of plays, films, books and so on – has acquired an understandably ambiguous sense. But this cannot be resolved by distinctions of status between critic and reviewer. What is at issue is not only the association between criticism and fault-finding but the more basic association between criticism and ‘authoritative’ judgment as apparently general and natural processes. As a term for the social or professional generalization of the processes of reception of any but especially the more formal kinds of COMMUNICATION (q.v.), criticism becomes ideological not only when it assumes the position of the consumer but also when it masks this position by a succession of abstractions of its real terms of response (as judgment, taste, cultivation, discrimination, sensibility; disinterested, qualified, rigorous and so on). The continuing sense of criticism as fault-finding is the most useful linguistic influence against the confidence of this habit, but there are also signs, in the occasional rejection of criticism as a definition of conscious response, of a more significant rejection of the habit itself. The point would then be, not to find some other term to replace it, while continuing the same kind of activity, but to get rid of the habit, which depends, fundamentally, on the abstraction of response from its real situation and circumstances: the elevation to ‘judgment’, and to an apparently general process, when what always needs to be understood is the specificity of the response, which is not an abstract ‘judgment’ but even where including, as often necessarily, positive or negative responses, a definite practice, in active and complex relations with its whole situation and context.

See AESTHETIC, CONSUMER, SENSIBILITY, TASTE

CULTURE (#ulink_7c6813c0-8584-5402-8935-ae38e5595244)

Culture is one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language. This is so partly because of its intricate historical development, in several European languages, but mainly because it has now come to be used for important concepts in several distinct intellectual disciplines and in several distinct and incompatible systems of thought.

The fw is cultura, L, from rw colere, L. Colere had a range of meanings: inhabit, cultivate, protea, honour with worship. Some of these meanings eventually separated, though still with occasional overlapping, in the derived nouns. Thus ‘inhabit’ developed through colonus

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: