По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

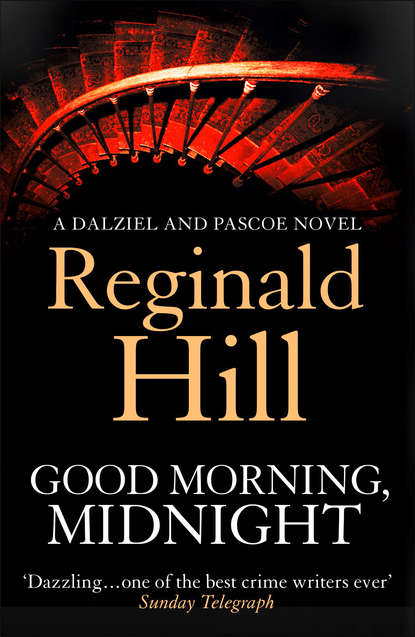

Good Morning, Midnight

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Mr Hat,’ said the witch. ‘Sit yourself down, Mr W. I’m just making a fresh pot of tea.’

She turned back to the stove. Hat studied Waverley openly and without embarrassment. (Pointless letting yourself be embarrassed in a dream.) Waverley returned the gaze with equal composure. He was in his early sixties, medium height, slim build, with a long narrow face, well-groomed hair, still vigorous though silvery, alert bluey-green eyes, and the sympathetic expression of a worldly priest who has seen everything and knows to the nearest farthing the price of forgiveness. He was wearing a beautifully cut grey mohair topcoat, which reminded Hat that despite the sunshine this was a pretty nippy morning.

He shivered, and this intrusion of meteorology bothered him like the name of the cottage. First the taste of food, now weather …

‘Do you live locally, Mr Hat?’ asked Waverley.

He had a gentle well-modulated voice with perhaps a faint Scots accent.

‘No,’ said Hat. ‘I got lost in the forest.’

‘The forest?’ echoed the man in a faintly puzzled tone.

‘I think Mr Hat means Blacklow Wood,’ said the witch with that nice smile.

‘Of course. And you’re quite right, Mr Hat. As you clearly know, this and one or two other little patches of woodland scattered around the area are all that remain of what used to be the great Blacklow Forest when the Plantagenets hunted here.’

Blacklow again. This time the vibration was strong enough to break the film of ice through which he viewed dreams and reality alike.

Now he remembered.

A dank autumn day … but his MG had been full of brightness as he drove deep into the heart of the Yorkshire countryside with the woman he loved by his side.

One of those small surviving patches of Blacklow Forest had been the copse out of which a deer had leapt, forcing him to bring his car to a skidding halt. Then he and she had pushed through the hedge and sat beneath a beech tree and drunk coffee and talked more freely and intimately than ever before. It had been a milestone in what had turned out to be far too short a journey.

Yesterday he’d driven out to the same spot and sat beneath the same tree, indifferent to the fall of darkness and the thickening mist. Nor when finally he rose and set off back to the car did he much care when he realized he’d missed his way. For an indeterminate period of time he’d wandered aimlessly, over rough grass and boggy fields, till he’d flopped down exhausted beneath another tree and slept.

The fog had cleared, the night had passed, the sun had risen, and he, waking under branches, imagined himself still sleeping and dreaming …

The woman placed the teapot on the table and said, ‘So what brings you out so early, Mr W?’

The man glanced at Hat, decided he was out of it for the moment, then said, ‘I’m afraid I’m the bearer of ill news, Miss Mac. I take it you’ve heard nothing?’

‘Heard what? You know I don’t have any truck with phones or wireless.’

‘Yes, I know. But I thought they might have … no, perhaps not … I’m sure that eventually someone will think …’

‘What, for heaven’s sake? Spit it out, man,’ said the woman in exasperation.

‘Perhaps you should sit down … As you will,’ said Waverley as the woman responded with a steely stare that wouldn’t have been out of place on a peregrine. ‘I heard it on the radio this morning, then rang to check details. It’s your nephew, Pal. It’s very bad, I’m afraid. The worst. He’s dead. Like your brother.’

‘Like …? You mean he …?’

‘Yes, I’m truly sorry. He killed himself last night. In Moscow House.’

‘Oh God,’ said the woman. ‘Laurence, you are again my bird of ill omen.’

Now she sat down.

It seemed to Hat, who had emerged from the depths of his introspection just in time to take in the final part of this exchange, that the soft chirruping of the birds, a constant burden since he entered the kitchen, now all at once fell still.

The woman too sat in complete silence for almost a minute.

Finally she said, ‘This is a shock, Laurence. I’m prepared for the shocks of my world, but not for this. Am I needed? Will anyone need me? Please advise me.’

‘I think you should come with me, Lavinia,’ said the man. ‘When you have spoken to people and found out what there is to find out, then you will know if you’re needed.’

The shock of the news had put them on first-name terms, observed Hat. It also underlined his obtrusive presence.

He stood up and said, ‘I think I should be on my way.’

‘Don’t be silly,’ said the woman. ‘Carry on with your breakfast. I think you need it. Laurence, give me five minutes.’

She stood up and went out. The birds resumed their chirruping.

Hat looked at Waverley and said uncertainly, ‘I really think I ought to go.’

‘No need to rush,’ said Waverley. ‘Miss Mac never speaks out of mere politeness. And you do look as if a little nourishment wouldn’t come amiss.’

No argument there, thought Hat.

He sat down and resumed eating his second slice of bread on which he’d spread butter and marmalade to a depth that had the robin tic-ticking in admiration and envy.

Waverley took two mugs from a shelf, and poured the tea.

‘Is there anywhere I can give you a lift to when we go?’ he said.

‘Thank you, I don’t know …’

It occurred to Hat he had no idea where he was in relation to his own vehicle.

To cover his uncertainty, he said, ‘Did you come by car? I didn’t hear it.’

‘I leave it by the roadside. You’ll understand why when you see the state of the track up to the cottage. Miss Mac doesn’t encourage callers.’

Was he being warned off?

Hat said, ‘But she makes them very welcome,’ with just enough stress on she for it to be a counter-blow if the man wanted to take it that way.

Waverley smiled faintly and said, ‘Yes, she has a soft spot for lame ducks, whatever the genus. There you are, my dear.’

Miss Mac had reappeared, having prepared for her outing by pulling a cracked Barbour over her T-shirt and changing her wellies for a pair of stout walking shoes.

‘Shall we be off? Mr Hat, you haven’t finished your tea. No need to rush. Just close the door when you leave.’

Hat caught Waverley’s eye and read nothing there except mild curiosity.

He said, ‘No, I’d better be on my way too. But I’d like to come again some time, if you don’t mind … Sorry, that sounds cheeky, I don’t want to be …’