По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

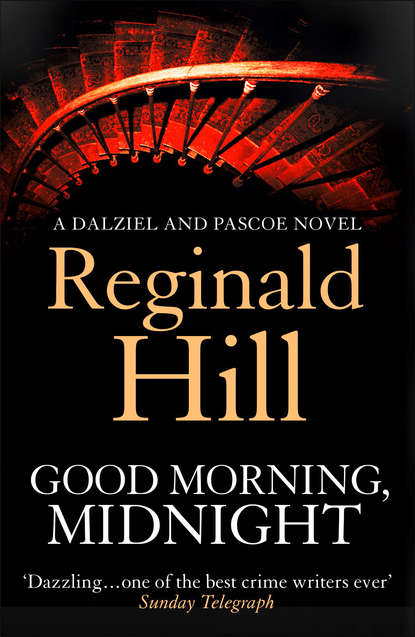

Good Morning, Midnight

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Of course you’ll come again,’ she interrupted as if surprised. ‘Good-looking young man who knows about birds, how should you not be welcome?’

‘Thank you,’ said Hat. ‘Thank you very much.’

He meant it. While he couldn’t say he was feeling well, he was certainly feeling better than he had done for weeks.

They went out of the door he’d come in by. She didn’t bother to lock it. Waste of time anyway with the window left open for the birds.

They went down the side of the cottage, Miss Mac leaning on the stick in her right hand and hanging on to Waverley’s arm with the other as they headed up a rutted track towards a car parked on a narrow country road about fifty yards away.

If Hat had thought of guessing what sort of car Waverley drove, he would probably have opted for something small and reliable, a Peugeot 307 for instance, or maybe a Golf. His enforced absence from work must have dulled his detective powers. Gleaming in the morning sunlight stood a maroon coloured Jaguar S-type.

He said, ‘That lift you offered me, my car’s on the old Stangdale road, if that’s not out of your way.’

‘My pleasure, Mr Hat,’ said Waverley. ‘My pleasure.’

2 (#ulink_056357d6-0ef2-5b36-b301-8052268ef82b)

the Kafkas at home (#ulink_056357d6-0ef2-5b36-b301-8052268ef82b)

Some miles to the south, close to the picturesque little village of Cothersley, dawn gave the mist still shrouding Cothersley Hall the kind of fuzzy golden glow with which unoriginal historical documentary makers signal their next inaccurate reconstruction. For a moment an observer viewing the western elevation of the building might almost believe he was back in the late seventeenth century just long enough after the construction of the handsome manor house for the ivy to have got established. But a short stroll round to the southern front of the house bringing into view the long and mainly glass-sided eastern extension would give him pause. And when further progress allowed him to look through the glass and see a table bearing a glowing computer screen standing alongside an indoor swimming pool, unless possessed of a politician’s capacity to ignore contradictory evidence, he must then admit the sad truth that he was still in the twenty-first century.

A man in a black silk robe sat by the table staring at the screen. He didn’t look up as the door leading into the main house opened and Kay Kafka appeared, clad in a white towelling robe on the back of which was printed IF YOU TAKE ME HOME YOUR ACCOUNT WILL BE CHARGED. She was carrying a tray set with a basket of croissants, a butter dish, two china mugs and an insulated coffee-pot.

Putting the tray on the table she said, ‘Good morning, Tony.’

‘He’s back.’

‘Junius?’ That was the great thing about Kay. You could talk shorthand with her. ‘Same stuff as before?’

‘More or less. Calls himself NewJunius now. Broke in again, left messages and a hyperlink.’

‘I thought they said that was impossible.’

‘They said boil-in-the-bag rice was impossible. His style doesn’t improve.’

‘You seem pretty laid-back about it.’

‘Why not? Some bits I even find myself agreeing with these days.’

‘What bits would they be?’

‘The bits where he suggests there’s more to being a good American than making money.’

‘You tried that one out on Joe lately?’ she asked casually.

‘You know I did, end of last year when the dust had started to settle after 9/11. There were no certainties any more. We talked about everything.’

‘Then after that Joe said it was business as usual, right?’

‘Not so. You’ve got Joe wrong. He feels things as strongly as me. I don’t see him face to face enough, that’s all.’

‘He’s only a flight away,’ she said gently.

It wasn’t a discussion she wanted to get into. Joe Proffitt, head of the Ashur-Proffitt Corporation, wasn’t a man she liked very much, but she didn’t feel able to speak out too strongly against him. Last September she knew that every instinct in Tony Kafka’s body had told him to head for home, permanently. But with Helen three months pregnant, he’d known how his wife would feel about that. So Tony was still here and, as far as she could detect, Joe Proffitt’s business certainties had hardly been dented at all.

‘Yeah, I ought to go more often. It’s as quick going to the States as it is getting to London with these goddam trains,’ he grumbled. ‘Look at me, up with the dawn so I can be sure to be in time for lunch barely a couple of hundred miles away.’

‘You’ll have time for some breakfast?’ she said.

‘No thanks. I’ll get some on the train. What time you get back last night?’

‘Late. Two o’clock maybe, I don’t know. You didn’t wait up.’

‘What for? You may not need sleep but I do, specially with an early start and a long hard day ahead speaking a foreign language.’

‘I thought it was just Warlove you were meeting?’

‘That’s the foreign language I mean.’ They smiled at each other. ‘Anyway, last night when you rang, you didn’t think there was anything there to lose sleep over. Has anything changed? I’ll get asked.’

‘You think they’ll know already?’

‘I’d put money on it,’ he said.

‘It’s cool,’ she said pouring herself some coffee. ‘Domestic drama, that’s all. Main thing is Helen’s fine and the twins don’t seem any the worse for being a tad early.’

‘Good. Born in Moscow House, eh? There’s a turn-up.’

‘Like their mother. Nature likes a pattern. She wants to call the girl Kay.’

‘Yeah, you said. And the boy?’

‘Last night she was talking about Palinurus. Of course she’s very upset over what happened and later she might get to thinking …’

‘A bit ill-omened? Right. And your fat friend is quite happy, is he?’

‘Copycat suicide, no problems.’

‘Copycat suicide? He doesn’t find that a bit weird?’

‘I think in his line of business he takes weird in his stride. I’m having a drink with him later, so I’ll get an update.’

‘Who was it said an update was having sex the first time you went out?’

‘You, I’d guess. No passes from Andy. He is, despite appearances, a kind man.’

‘Yeah,’ he said, as if unconvinced.

Silence fell between them broken by the distant chime of the old long-case clock standing in the main entrance hall. Though it looked as if it had been there almost as long as the house, in fact it had come later than its owners. Kay had spotted it in an antique shop in York. When she’d pointed out the inscription carved on the brass dial – Hartford Connecticut 1846 – Tony had laughed and said, ‘Real American time at last!’ She’d gone back later and bought it for his birthday. He’d been really touched. It turned out to have a rather loud chime which she’d wanted to muffle, but he’d refused, saying, ‘We need to make ourselves heard over here!’ In return, however, he’d conceded when she resisted his proposal to set it five hours behind Greenwich Mean Time.