По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

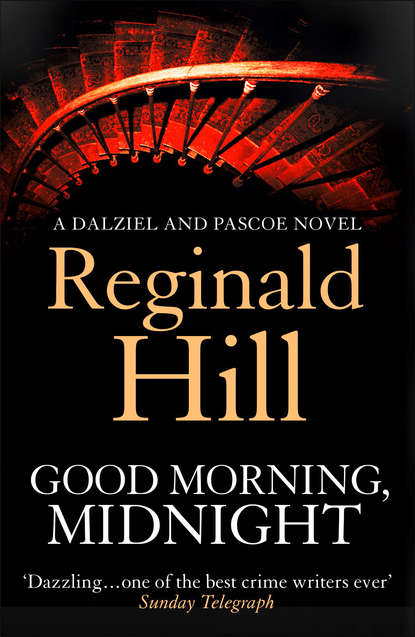

Good Morning, Midnight

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Now its brassy note rang out eight times.

‘Gotta go,’ said Kafka. ‘Let me know how you get on with Mr Blobby, if you’ve a moment.’

‘Sure. Tony, you’re not worried?’

‘No. Just like to show those bastards I’m on top of things.’

‘You’re sure they’re not getting on top of you?’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘I don’t know … sometimes you get so restless … last night when I got in you were tossing and turning like you were at sea.’

For a moment he seemed about to dismiss her worries, then he shrugged and said, ‘Just the old thing. I dream I hear the fire bells and I know I’ve got to get home but I can’t find the way …’

‘Then you wake up and you’re home and everything’s fine, Right, Tony? This is our home.’

‘Yeah, sure. Only sometimes I think I feel more foreign here than anywhere. Sorry, no. I don’t mean right here with you. That’s great. I mean this fucking country. Maybe all I mean is that America’s where all good Americans ought to be right now. We are good Americans, aren’t we, Kay?’

‘As good as we can be, Tony. That’s all anyone can ask.’

‘I think a time’s coming when they can ask a fucking sight more,’ he said.

Abruptly he stood up, removed his black robe and stood naked before her except for the thin gold chain he always wore round his neck. On it was his father’s World War Two Purple Heart, which he wore as a good-luck charm.

‘Pay me no heed,’ he said. ‘Male menopause. I could pay a shrink five hundred dollars a session to tell me the same. Give my best to Helen.’

He turned away and dived into the swimming pool.

He was in his late forties, but his stocky body, its muscles sculpted into high definition by years of devoted weight training, showed little sign yet of paying its debt to age.

He did a length of crawl, tumble turned, and came back at a powerful butterfly. Back where he started, his final stroke brought his flailing arms down on to the lip of the pool and he hauled himself out in one fluid movement.

When he stops that trick, I’ll know he’s over the hill physically, thought Kay.

But where he was mentally, even her penetrating gaze couldn’t assess.

She watched him walk away, his feet stomping down hard on the tiled floor as if he’d have liked to feel it move. When he vanished through the door, she turned the laptop towards her and began to read.

ASHUR-PROFFITT & THE CLOAK OF INVISIBILITY

A Modern Fairy Tale

Once upon a time some cool dudes in the Greatest Country on Earth decided it would be real neat to sell arms to one bunch of folk they didn’t like at all called the Iranians and give the profits from the sale to another bunch of folk they liked a lot called the Contras. At the same time across the Big Water in the Second Greatest Country on Earth some other cool dudes decided it would be real neat to sell arms to another bunch of folk called the Iraqis that nobody liked much except that they were fighting another bunch of folk called the Iranians that no one liked at all. But it didn’t bother the cool dudes in either of the two Greatest Countries on Earth to know what the other was doing because in each of the countries there were people doing that too and as Mr Alan Clark of the second G.C.O.E. (who was so cool, if he’d been any cooler he’d have frozen over) remarked later, ‘The interests of the West were best served by Iran and Iraq fighting each other, and the longer the better.’

But the really amazing thing about all these dudes on both sides of the Big Water was that they were totally invisible – which meant that, despite the fact that everything they did was directly contrary to their own laws, nobody in charge of the two Greatest Countries on Earth could see what they doing!

She scrolled to the end, which was a long way away. Tony was right about the style. Once this kind of convoluted whimsicality had probably seemed as cool as you could get without taking your clothes off. Now it was just tedious, which was good news from A-P’s point of view. Only the final paragraph held her attention.

There was a time when you could argue a patriotic case – my enemy’s enemy is my friend so treat them all the same then sit back and watch them knock hell out of each other – but no longer. Hawk or dove, republican or democrat, every good American knows there’s a line in the sand and anyone who sends weapons across this line had better be sure which way they’re going to be pointing. The Ashur-Proffitt motive is no longer enough. It’s time we asked these guys just whose side they think they’re on.

She sat back and thought of Tony, of his admission that he felt foreign here. Could it be that now that the twins were born, he thought she might be persuadable to up sticks and head west? Funny that it should come to this, that he whose own father had been born God knows where should be the one who spoke of being a good American and going home, while she whose forebears, from what she knew of them, had been good Americans for at least a couple of centuries, could not bring to mind a single place in the States – save for one tiny plot covering a very few square feet – that exerted any kind of emotional pull. OK, so she agreed, home was a holy thing, but to her this was home, all the more holy since last night. Tony would have to understand that.

The script had vanished to be replaced by a screen saver – the Stars and Stripes rippling in a strong breeze.

She switched it off, leaned back in her chair and closed her eyes. Tony was right. She didn’t need much sleep and she’d perfected the art of dropping off at will for a pre-programmed period. This time she gave herself forty minutes.

When she woke, the sun was up and the mist was rising. She stood up, undid her robe, let it slide to the floor, and dived into the pool. Her slim naked body entered the water with barely a splash and what trace of her entry there was had almost vanished by the time she broke the surface two-thirds of a length away.

She swam six lengths with a long graceful breast stroke. Her exit from the pool was more conventional than her husband’s but in its own way just as athletic.

She slipped into her robe. The legend on the back didn’t amuse her but it amused Tony and his bad jokes were a small price to pay for all he’d done for her. But some stuff she needed to deal with herself. Like last night. Something had happened that she didn’t understand. If she could work it out and defend herself against it, she would. But if it turned out to be part of that darkness against which there was no defence, so what? She’d dealt with darkness before.

In any case, it was trivial alongside the thing that had happened that she did understand. The birth of Helen’s twins. Most dawns were false but you enjoyed the light even if you knew it was illusory.

Whistling ‘Of Foreign Lands and People’ from Schumann’s Childhood Scenes she walked back through the door into the house.

3 (#ulink_c82244f0-c914-5a1b-bc14-2c29b7bbd198)

a nice vase (#ulink_c82244f0-c914-5a1b-bc14-2c29b7bbd198)

By ten o clock that morning, with the curtaining mist raised by a triumphant sun and the brisk breeze that cued the wild daffodils to dance at Blacklow Cottage rattling the slats on his office blinds, Pascoe was far less certain about his uncertainties.

Dalziel had no doubts. His last words had been, ‘Tidy this up, Pete, then dump the lot on Paddy Ireland’s desk. Suicides are Uniformed’s business.’

He was right, of course, except that his idea of tidiness wasn’t the same as Pascoe’s, which was why on his way to work he diverted to the cathedral precinct where Archimagus Antiques was situated.

The closed sign was still displayed in the shop door, but when he peered through the window he saw someone moving within. He banged on the window. A woman appeared, mouthed ‘Closed’ and pointed at the sign. Pascoe in return pressed his warrant against the glass. She nodded instantly and opened the door.

‘I didn’t know what to do,’ she began even before he stepped inside. ‘It was on the news, you see, and I didn’t know if I should come in or not, but David said he thought I should, not to do business, but just in case someone from the police wanted to ask questions, which you clearly do, so he was right, and he’d have come with me but he felt he ought to go round to see poor Sue-Lynn, and I would have gone with him only it seemed better for me to come here.’

She paused to draw breath. She was tall, well made and attractive in a Betjeman tennis girl kind of way. As she spoke she ran her fingers through her short unruly auburn hair. Breathlessness suited her. Early twenties, Pascoe guessed, and with the kind of accent which hadn’t been picked up at the local comp. She was dressed, perhaps fittingly but not too becomingly, in a white silk blouse and a long black skirt. She looked tailor-made for jodhpurs, a silk headsquare and a Barbour.

‘I’m DCI Pascoe,’ he said. ‘And you are …?’

‘Sorry, silly of me, I’m babbling on and half of what I say can’t mean a thing. I’m Dolly Upshott. I work here. Partly shop assistant, I suppose, but I help with the accounts, that sort of thing, and I’m in charge when Pal’s off on a buying expedition. Please, can you tell me anything about what happened?’

‘And this David you mentioned is …?’ said Pascoe, who’d learned from his great master that the easiest way to avoid a question was to ask another.

‘My brother. He’s the vicar at St Cuthbert’s, that’s Cothersley parish church.’

Which was where the Macivers lived, in a house with the unpromising name of Casa Alba. Cothersley was one of Mid-Yorkshire’s more exclusive dormer villages. The Kafkas’ address was Cothersley Hall. Family togetherness? Didn’t seem likely from what he’d gathered about internal relationships last night. Also it was interesting that the brash American incomers should occupy the Hall while Maciver with his local connections and his antique-dealer background should live in a house that sounded like a rental villa on the Costa del Golf.

‘And he’s gone to comfort Mrs Maciver? Very pastoral. Were they active churchgoers then?’

‘No, not really. But they are … were … very supportive of church events, fêtes, shows, that sort of thing, and very generous when it came to appeals.’

What Ellie called the Squire Syndrome. Well-heeled townies going to live in the sticks and acting like eighteenth-century lords of the manor.