По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

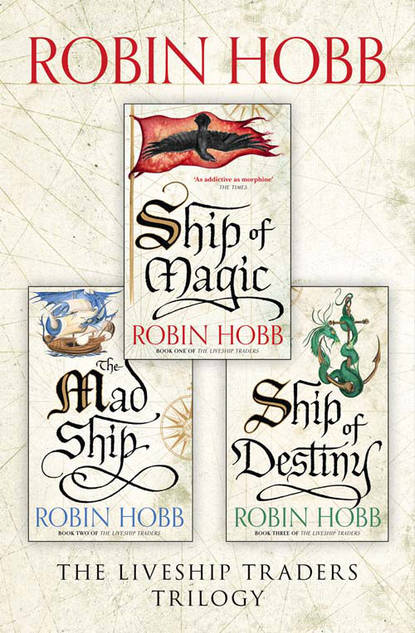

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Like what?’ he demanded.

She could not stop herself. ‘Like having a greedy fool for a son-in-law. You don’t know what you’re talking about when you speak of the Rain River.’

Kyle gave her an icy smile. ‘Why don’t you give me the charts then, and let me find out? If you’re right, you’ll be rid of me as a son-in-law. You’ll be free to sink all your children and grandchildren into debt.’

‘No!’ Keffria started up with a shriek. ‘I can’t stand this! Don’t talk about things like that. Kyle, you mustn’t go up the Rain River. Slaves are far better, trade in slaves, and take Wintrow with you if you must, but you mustn’t go up the Rain River!’ She looked at them both pleadingly. ‘He would never come back. We both know that. Papa’s only just died and now you’re talking about letting Kyle get himself killed.’

‘Keffria. You’re overwrought, and over-reacting to everything.’ The look Kyle shot Ronica suggested it was her fault for playing upon her daughter’s imagination. A tiny spark of anger kindled in Ronica’s heart, but she doused it firmly, for her daughter was looking at her husband with eyes full of hurt. Opportunity, she breathed to herself. Opportunity.

‘Let me take care of her,’ she suggested smoothly to Kyle. ‘I’m sure you have so much to do to ready the ship. Come, Keffria. Let’s go to my sitting room. I’ll have Rache bring us some tea. In truth, I feel a bit overwrought myself. Come. Let’s leave things to Kyle for a while.’

She stood and slipped an arm around Keffria and led her from the room. Salvage, she silently whispered to Ephron. I’ll salvage what I can of what you left me, my dear. At least one daughter I shall keep safe by me.

11 CONSEQUENCES AND REFLECTIONS (#ulink_c0d20c03-a904-5884-b5e8-1423bb8135b7)

‘AND IF I WISHED to dispute these documents?’ Althea asked slowly. She tried to make her voice impartially calm, but inside she was quivering with both anger and hurt.

Curtil scratched reluctantly at what was left of his greying hair. ‘That is specifically provided for. Anyone who disputes this last testament is automatically excluded from benefiting from it.’ He shook his head, almost apologetically. ‘It’s a standard thing,’ he told her gently. ‘It’s not as if your father was thinking specifically of you when we wrote it.’

She looked up from her tangled hands and met his eyes firmly. ‘And you believe this is actually what he wished? That Kyle take over Vivacia, and I be dependent on my sister’s charity?’

‘Well, I doubt that is how he envisioned it,’ Curtil said judiciously. He took a sip of his tea. Althea wondered if that were a delaying tactic, to give him time to think. The old man straightened in his chair as if he’d decided something. ‘But I do believe he knew his own mind. No one deceived him or coerced him. I would never have been a party to that. Your father wished to see your sister as his sole heir. He did not desire to punish you, but rather to safeguard his entire family.’

‘Well, in both of those desires he failed,’ Althea said harshly. Then she lowered her face into her hands, ashamed to have spoken so of her father. Curtil let her be. When she lifted her face some time later, she observed, ‘You must think me a carrion bird. Yesterday my father died, and today I come quarrelling for a share of what was his.’

Curtil offered her his handkerchief and she took it gratefully. ‘No. No, I don’t think that. When the mainstay of one’s world is taken away, it’s only natural to cling to all the rest, to try desperately to keep things as close to the way they were as one can.’ He shook his head sorrowfully. ‘But no one can ever go back to yesterday.’

‘No. I suppose not.’ She sighed heavily. She considered her last pathetic straw of hope. ‘Trader Curtil. By Bingtown law, if a man swears an oath to Sa, cannot he be held to that oath as a legal contract?’

Curtil’s long brow furrowed. ‘Well. It depends. If in a fit of anger, in a tavern, I say that by Sa, I’m going to kill so-and-so, well, that’s not a legal action in the first place, so…’

Althea stopped mincing words. ‘If Kyle Haven swore before witnesses that if I could produce proof that I was a worthy seaman, he would give Vivacia back to me, if he swore that in Sa’s name, could it be enforced?’

‘Well, technically, the ship is your sister’s property, not his—’

‘She has ceded control of it over to him,’ Althea said impatiently. ‘Is such an oath legally binding?’

Curtil shrugged. ‘You’d end up before the Traders’ Council, but, yes, I think you’d win. They’re conservative, the old customs count for much with them. An oath sworn before Sa would have to be legally honoured. You have witnesses to this, at least two?’

Althea leaned back in her chair with a sigh. ‘One, perhaps, who would speak up for the truth of what I say. The other two… I no longer know any more what I could expect of my mother and sister.’

Curtil shook his head. ‘Family disputes such as these are such messy things. I counsel you not to pursue this, Althea. It can only lead to even worse rifts.’

‘I do not believe that it can get any worse,’ she observed grimly, before bidding him farewell.

She was her father’s daughter. She had gone immediately to Curtil in his offices. The old man had not seemed at all surprised to see her. As soon as she was shown into his chambers, he rose and took down several rolled documents. One after another, he set them before her, and made plain to her just how untenable her position was. She had to give her mother credit for thoroughness; the whole thing was lashed down like storm-weather cargo. Legally, she had nothing. Legally, she was dependent entirely on her sister’s goodwill.

Legally. She did not intend that her reality would have anything to do with that kind of legality. She would not live off Keffria’s charity, especially not if it meant she would have to dance to Kyle’s tunes. No. Let them go on thinking her father had died and left her nothing. They’d be wrong. All he had taught her, all her knowledge of the sailing trade and her observations of his trading were still hers. If she could not make her own way on that, then she deserved to starve. Stoutly she told herself that when the first Vestrit came to Bingtown, he probably knew little more than that, and he had made his own way. She should be able to do as much for herself.

No. More than that. She’d get the proof that she was all she said she was, and she’d hold Kyle to his oath. Wintrow, she was sure, would support her. It was his only way out from under his father’s thumb. But would her mother or Keffria? Althea considered. She did not think they would willingly do so. On the other hand, she did not think they would speak before the Traders’ Council and lie. Her resolve firmed itself. One way or another, she’d stand up to Kyle and claim what was rightfully hers.

The docks were busy. Althea picked her way down to where Vivacia was tied, side-stepping men with barrows, freight wagons drawn by sweating horses, chandlers making deliveries of supplies to outbound ships and merchants hastening to inspect their incoming shipments before taking delivery. Once the hustle of the midday business on the docks would have excited her. Now it weighed her spirits. Abruptly she felt excluded from these lives, set apart and invisible. When she walked the docks dressed as befitted a daughter of a Bingtown Trader, no sailor dared to notice her, let alone call out a cheery greeting to her. It was ironic. She had chosen the simple dark dress and laced sandals that morning as a partial apology to her mother for how badly she had behaved the night before. She had little expected that it would become her sole fortune as she set off on her own into the world.

But as she walked down the docks, her confidence peeled away from her. How was she to employ such knowledge to feed herself? How could she approach any ship’s captain or mate, dressed as she was, and convince him that she was an able-bodied sailor? While female sailors were not rare in Bingtown, they were not all that common either. One frequently saw women working the decks of Six Duchies ships when they came to Bingtown. Many of the Three-Ships’ Immigrants had become fisherfolk, and among them, family ships were worked by the whole family. So while female sailors were not unknown in Bingtown, she’d be expected to prove herself just as tough or tougher than the men she’d have to work alongside. But she wouldn’t even be given the chance to try, dressed as she was. As the rising heat of the day made her uncomfortably aware of the weight and breadth of her dark skirts and modest jacket, she longed more and more for simple canvas trousers and a cotton shirt and vest.

Finally she stood beside Vivacia. She glanced up at the figurehead. To anyone else, it would have appeared that the ship was dozing in the sun. Althea did not even need to touch her to know that in actuality, the ship’s senses and thoughts were turned inward, keeping track of her own unloading. That job was proceeding apace, with longshoremen streaming down her gangplanks burdened with the variety of her cargo like ants fleeing a disturbed nest. They paid scant attention to her; Althea was just another gawker on the docks. She ventured closer to Vivacia and set a hand to her sun-warmed planking. ‘Hello,’ she said softly.

‘Althea.’ The ship’s voice was a warm contralto. She opened her eyes and smiled down at Althea. Vivacia extended a hand towards her, but lightened as she was, she floated too high for their hands to reach. Althea had to content herself with the sensations she received through the rough planking her hand rested on. Already her ship had a much greater sense of self. She could speak to Althea, and still keep awareness of cargo as it was shifted in her holds. And, Althea realized with a pang, she focused much of her awareness on Wintrow. The boy was in the chain locker, coiling and stowing lines. The heat of the tiny enclosed room was oppressive, while the thick ship’s smell all around him made him nauseated. The distress he felt had spread through the ship as a tension in the planking and a stiffness to the spars. Here, tied to the dock, that was not so bad, but out in the open sea a ship had to be able to give with the pressures of the water and wind.

‘He’ll be all right,’ Althea told Vivacia comfortingly, despite the jealousy she felt over the ship’s concern. ‘It’s a hard and boring task for a green hand, but he’ll survive it. Try not to think of his discomfort right now.’

‘It’s worse than that,’ the ship confided quietly. ‘He’s all but a prisoner here. He doesn’t want to be aboard, he wants to be a priest. We started out to be such wonderful friends, and now I think they are making him hate me.’

‘No one could hate you,’ Althea assured her, and tried to make her words sound confident. ‘He does want to be somewhere else; there’s no use in my lying to you about that. So what he hates is not being where he wants to be. He couldn’t possibly hate you.’ Steeling herself, as if she plunged her hand into fire, she added, ‘You can be his strength, you know. Let him know how much you value him, and what a comfort it is to you that he is aboard. As you once did for me.’ Try as she might, she could not keep her voice from breaking on the last words.

‘But I am a ship, not your child,’ Vivacia replied to Althea’s unvoiced thought rather than her words. ‘You are not giving up a little child with no knowledge of the world. I know in many ways I am naive still, but I have a wealth of memories and information to draw on. I just need to put them in some sort of order, and see how they relate to who I am now. I know you, Althea. I know you did not abandon me by choice. But you also know me. And you must understand how deeply it hurts me when Wintrow is forced to be aboard me, forced to be my companion and heart’s friend when he wishes he were elsewhere. We are drawn to one another, Wintrow and I. But his anger at the situation makes him resist that bond. And it makes me ashamed that I so often reach toward him.’

The division within the ship’s heart was terrible to feel. Vivacia battled her own need for Wintrow’s companionship, forcing herself to stand still in a cold isolation that was grey as fog. Almost Althea could sense it as a terrible place, rainswept and chill and endlessly grey. It appalled her. As Althea searched for comforting words, a man’s voice rang out loud and commanding over the ordinary dock yells and thuds. ‘You. You there! Get away from the ship! Captain’s orders, you aren’t to come aboard her.’

Althea tipped her head back, shielding her eyes against the sun’s glare. She stared up at Torg as if she had not recognized his voice. ‘This, sir, is a public dock,’ she pointed out calmly.

‘Well, this ain’t a public ship. So shove off!’

As little as two months ago, Althea would have exploded at him. But the time she had spent secluded with Vivacia and the events of the last three days had changed her. It was not that she was a better-tempered person, she decided detachedly. It was that her anger had learned a terrible patience. What good was wasting words on a petty and tyrannical second mate? He was a little yapping dog. She was a tigress. One did not waste snarls on such a creature. You waited until you could snap his spine with a single blow. He had sealed his fate with his mistreatment of Wintrow. His rudeness to Althea would be redeemed at the same time.

And with a wave of giddiness, Althea realized that while her hand rested on the planking, her thoughts were Vivacia’s and Vivacia’s were hers. Belatedly she pulled free of the ship, feeling as if she drew her hand out of cold, wrist-deep molasses. ‘No, Vivacia,’ Althea said quietly. ‘Do not let my anger become your own. And leave vengeance to me, do not soil yourself with it. You are too big, too beautiful; it is unworthy of you.’

‘He is unworthy of my deck, then,’ Vivacia replied in a low, bitter voice. ‘Why must I tolerate vermin like him while you are put ashore? You cannot tell me it is the Vestrit way to treat kinsmen so.’

‘No. No, it is not,’ Althea hastily assured her.

‘I said, move on,’ Torg shouted once more from the deck above her. Althea glanced up at him. He was leaning over the railing, shaking his fist at her. ‘Move along, or I’ll have you moved along!’

‘There’s really nothing he can do,’ Althea assured the ship. But even as she spoke, she heard a muffled cry and then a heavy thud from within Vivacia’s hold. Someone cursed fluently on the deck, followed by cries for Torg. A young sailor’s voice floated up clearly. ‘The hoist tackle’s pulled free of the beam, sir! I’d swear it was set sound enough when we started work.’

Torg’s head disappeared and Althea heard the sound of his feet running across the deck. The unloading of Vivacia’s cargo ground to a halt as half the crew came to gawk at the smashed pallet and crates and the scattered comfer nuts. ‘That should keep him busy for a time,’ Vivacia observed sweetly.

‘I do have to leave, though,’ Althea hastily decided. If she stayed, she would have to ask the ship if she had had anything to do with the fallen block-and-tackle. ‘Take care of yourself,’ she told Vivacia. ‘And look after Wintrow, too.’

‘Althea! Will you be back?’

‘Of course I will. There are just a few things I need to take care of. But I’ll be back to see you again before you sail.’

‘I can’t imagine sailing without you,’ Vivacia said desolately. The figurehead lifted her eyes to the distant horizon, as if she were already far beyond Bingtown. A stray breeze stirred the heavy locks of her hair.

‘It’s going to be hard to stand here on the docks and watch you go off into the distance. At least you’ll have Wintrow aboard.’

‘Who hates being with me.’ The ship abruptly sounded very young again. And very distressed.