По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

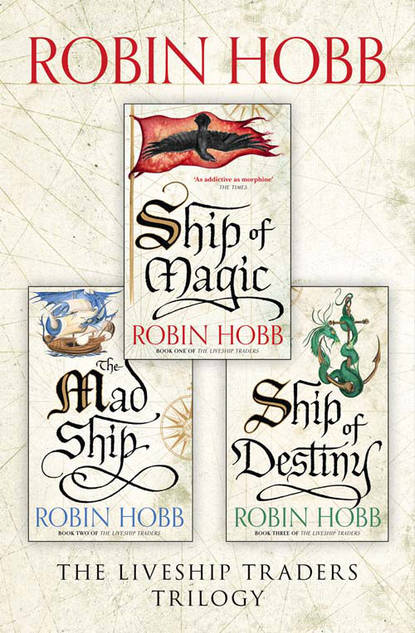

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I suppose I do. You do not come often. And your father roaring at us when he found you here with me is what I remember best about you. He called me a “damnable piece of wreckage” and “the worst sort of luck one could have”.’

She sounded almost ashamed as she replied, ‘Yes. I remember that too, very clearly.’

‘Probably not as clearly as I. But then, you probably have a greater variety of memories to choose from.’ He added petulantly, ‘One does not gather many unique memories, hauled out on a beach.’

‘I am sure you had a great many adventures in your day,’ Althea offered.

‘Probably. It would be nice if I could remember any of them.’

He heard her come closer. From the shifting in the angle of her voice, he judged she had sat down on a rock on the beach. ‘You used to speak to me of things you remembered. When I was a little girl and came here, you told me all sorts of stories.’

‘Most of them were lies, I expect. I don’t remember. Or maybe I did then, but no longer do. I think I am getting vaguer. Brashen thinks it might be because my log is missing. He says I do not seem to recall as much of my past as I used to.’

‘Brashen?’ A sharp edge of surprise in her voice.

‘Another friend,’ Paragon replied carelessly. It pleased him to shock her with the news he had another friend. Sometimes it irritated him that they expected him to be so pleased to see them, as if they were the only people he knew. Though they were, they should not have been so confident of it, as if it were impossible a wreck such as he might have made other friends.

‘Oh.’ After a moment, Althea added, ‘I know him as well. He served on my father’s ship.’

‘Ah, yes. The… Vivacia. How is she? Has she quickened yet?’

‘Yes. Yes, she has. Just two days ago.’

‘Really? Then it surprises me you are here. I thought you would rather be with your own ship.’ He had had all the news from Brashen already, but it gave him an odd pleasure to force Althea to speak of it.

‘I suppose I would be, if I could,’ the girl admitted unwillingly. ‘I miss her so much. I need her so badly just now.’

Her honesty caught Paragon off-guard. He had accustomed himself to think of people as givers of pain. They could move about so freely and end their lives at any time they chose; it was hard for him to understand that she could feel such a depth of pain as her voice suggested. For a moment, somewhere in the labyrinths of his memory a homesick boy sobbed into his bunk. Paragon snatched his consciousness back from it. ‘Tell me about it,’ he suggested to Althea. He did not truly want to hear her woes, but at least it was a way to keep his own at bay.

It surprised him when she complied. She spoke long, of everything, from Kyle Haven’s betrayal of her family’s trust to her own incomplete grief for her father. As she spoke, he felt the last warmth of the afternoon ebb away and the coolness of night come on. At some time she left her rock to come and lean her back against the silvered planking of his hull. He suspected she did it for the warmth of the day that lingered in his bones, but with the nearness of her body came a greater sharing of her words and feelings. It was almost as if they were kin. Did she know that she reached toward him for understanding as if he were her own liveship? Probably not, he told himself harshly. It was probably just that he reminded her of Vivacia and so she extended her feelings into him. That was all. It was not especially intended for him.

Nothing was especially intended for him.

He forced himself to remember that, and so he could be calm when, after she had been silent for some time, she said, ‘I have no place to stay tonight. Could I sleep aboard?’

‘It’s probably a smelly mess in there,’ he cautioned her. ‘Oh, my hull is sound enough, still. But one can do little about storm waters, and blown sand and beach lice can find a way into anything.’

‘Please, Paragon. I won’t mind. I’m sure I can find a dry corner to curl up in.’

‘Very well, then,’ he conceded, and then hid his smile in his beard as he added, ‘if you don’t mind sharing space with Brashen. He comes back here every night, you know.’

‘He does?’ Startled dismay was in her voice.

‘He comes and stays almost every time he makes port here. It’s always the same. The first night it’s because it’s late and he’s drunk and he doesn’t want to pay a full night’s lodging for a few hours’ sleep and he feels safe here. And he always goes on about how he’s going to save his wages and only spend a bit of it this time, so that some day he’ll have enough saved up to make something of himself.’ Paragon paused, savouring Althea’s shocked silence. ‘He never does, of course. Every night he comes stumbling back, his pockets a bit lighter, until it’s all gone. And when he has no more to spend on drink, then he goes back and signs on whatever ship will have him until he ships out again.’

‘Paragon,’ Althea corrected him gently. ‘Brashen has worked the Vivacia for years now. I think he always used to sleep aboard her when he was in port here.’

‘Well, but, yes, I suppose so, but I meant before that. Before that, and now.’ Without meaning to, he spoke his next thought aloud. ‘Time runs together and gets tangled up, when one is blind and alone.’

‘I suppose it would.’ She leaned her head back against him and sighed deeply. ‘Well. I think I shall go in and find a place to curl up, before the light is gone completely.’

‘Before the light is gone,’ Paragon repeated slowly. ‘So. Not completely dark yet.’

‘No. You know how long evening lingers in summer. But it’s probably black as pitch inside, so don’t be alarmed if I go stumbling about.’ She paused awkwardly, then came to stand before him. Canted as he was on the sand, she could reach his hand easily. She patted it, then shook it. ‘Good night, Paragon. And thank you.’

‘Good night,’ he repeated. ‘Oh. Brashen has been sleeping in the captain’s quarters.’

‘Right. Thank you.’

She clambered awkwardly up his side. He heard the whisper of fabric, lots of it. It seemed to encumber her as she traversed his slanting deck and finally fumbled her way down into his cargo hold. She had been more agile as a girl. There had been a summer when she had come to see him nearly every day. Her home was somewhere on the hillside above him; she spoke of walking through the woods behind her home and then climbing down the cliffs to him. That summer she had known him well, playing all sorts of games inside him and around him, pretending he was her ship and she his captain, until word of it came to her father’s ears. He had followed her one day, and when he found her talking to the cursed ship, he soundly scolded them both and then herded Althea home with a switch. For a long time after that she had not come to see him. When she did come, it was only for brief visits in early dawn or evening. But for that one summer, she had known him well.

She still seemed to remember something of him, for she made her way through his interior until she came to the aft space where the crew used to hang their hammocks. Odd, how the feel of her inside him could stir such memories to life again. Crenshaw had had red hair and was always complaining about the food. He had died there, the hatchet that ended his life had left a deep scar in the planking as well, his blood had stained the wood…

She curled up against a bulkhead. She’d be cold tonight. His hull might be sound, but that didn’t keep the damp out of him. He could feel her, still and small against him, unsleeping. Her eyes were probably open, staring into the blackness.

Time passed. A minute or most of the night. Hard to tell. Brashen came down the beach. Paragon knew his stride and the way he muttered to himself when he’d been drinking. Tonight his voice was dark with worry and Paragon judged he was close to the end of his money. Tomorrow he would rebuke himself long for his stupidity, and then go out to spend the last of his coins. Then he’d have to go to sea again.

Paragon would almost miss him. Having company was interesting and exciting. But also annoying and unsettling. They made him think about things better left undisturbed.

‘Paragon,’ Brashen greeted him as he drew near. ‘Permission to come aboard.’

‘Granted. Althea Vestrit’s here.’

A silence. Paragon could almost feel him goggling up at him. ‘She looking for me?’ Brashen asked thickly.

‘No. Me.’ It pleased him inordinately to give the man that answer. ‘Her family has turned her out, and she had nowhere else to go. So she came here.’

‘Oh.’ Another pause. ‘Doesn’t surprise me. Well, the sooner she gives up and goes home, the wiser she’ll be. Though I imagine it will take her a while to come to that.’ Brashen yawned hugely. ‘Does she know I’m living aboard?’ A cautious question, one that begged for a negative answer.

‘Of course,’ Paragon answered smoothly. ‘I told her that you had taken the captain’s cabin and that she’d have to make do elsewhere.’

‘Oh. Well, good for you. Good for you. Good night, then. I’m dead on my feet.’

‘Good night, Brashen. Sleep well.’

A few moments later, Brashen was in the captain’s quarters. A few minutes after that, Paragon felt Althea uncurl. She was trying to move quietly, but she could not conceal herself from him. When she finally reached the door of the aftercastle chamber where Brashen had strung his hammock, she paused. She rapped very lightly on the panelled door. ‘Brash?’ she said cautiously.

‘What?’ he answered readily. He had not been asleep, nor even near sleep. Could he have been waiting? How could he have known she would come to him?

Althea took a deep breath. ‘Can I talk to you?’

‘Can I stop you?’ he asked grumpily. It was evidently a familiar response, for Althea was not put off by it. She set her hand to the door handle, then took it away without opening the door. She leaned on the door and spoke close to it.

‘Do you have a lantern or a candle?’

‘No. Is that what you wanted to talk about?’ His tone seemed to be getting brusquer.

‘No. It’s just that I prefer to see the person I’m talking to.’