По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

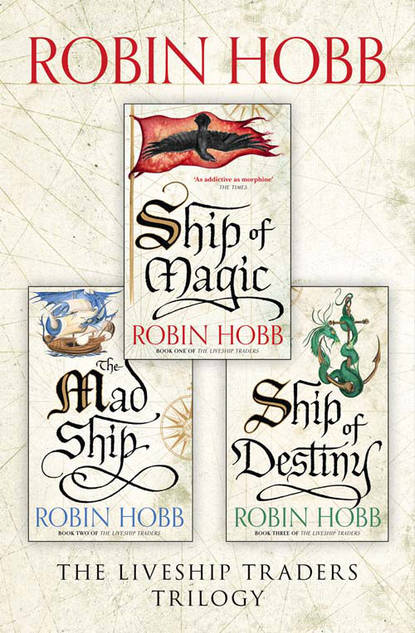

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A whisper light as a wraith’s sigh. ‘Yes, dear. Mother’s here.’ Ronica replied to it as quietly. She did not open her eyes. She knew these voices, had known them for years. Her little sons still sometimes came, to call to her in the darkness. Painful as such fancies were, she would not open her eyes and disperse them. One held on to what comforts one had, even if they had sharp edges.

‘Mother, I’ve come to ask your help.’

Ronica opened her eyes slowly. ‘Althea?’ she whispered to the darkness. Was there a figure just outside the window, behind the blowing curtains. Or was this just another of her night fancies?

A hand reached to pull the curtain out of the way. Althea leaned in on the sill.

‘Oh, thank Sa you’re safe!’

Ronica rolled hastily from her bed, but as she stood up, Althea retreated from the window. ‘If you call Kyle, I’ll never come back again,’ she warned her mother in a low, rough voice.

Ronica came to the window. ‘I wasn’t even thinking of calling Kyle,’ she said softly. ‘Come back. We have to talk. Everything’s gone wrong. Nothing’s turned out the way it was supposed to.’

‘That’s hardly news,’ Althea muttered darkly. She ventured closer to the window. Ronica met her gaze, and for an instant she looked down into naked hurt. Then Althea looked away from her. ‘Mother… maybe I’m a fool to ask this. But I have to, I have to know before I begin. Do you recall what Kyle said, when… the last time we were all together?’ Her daughter’s voice was strangely urgent.

Ronica sighed heavily. ‘Kyle said a great many things. Most of which I wish I could forget, but they seem graven in my memory. Which one are you talking about?’

‘He swore by Sa that if even one reputable captain would vouch for my competency, he’d give my ship back to me. Do you remember that he said that?’

‘I do,’ Ronica admitted. ‘But I doubt that he meant it. It’s just his way, to throw such things about when he is angry.’

‘But you do remember him saying it?’ Althea pressed.

‘Yes. Yes, I remember he said that. Althea, we have much more important things to discuss than this. Please. Come in. Come back home, we need to…’

‘No. Nothing is more important than what I just asked you. Mother, I’ve never known you to lie. Not when it was important. The time will come when I’ll be counting on you to tell the truth.’ Incredibly, her daughter was walking away, speaking over her shoulder as she went. For one frightening instant, she looked so like her father as a young man. She wore the striped shirt and black trousers of a sailor on shore. She even walked as he had, that roll to her gait, and the long dark queue of hair down her back.

‘Wait!’ Ronica called to her. She sat down on the window sill and swung her legs over it. ‘Althea, wait!’ she cried out, and jumped down into the garden. She landed badly, her bare feet protesting the rocky walk under her window. She nearly fell, but managed to catch herself. She hastened across a sward of green to the thick laurel hedge that bounded it. But when she reached it, Althea was already gone. Ronica set her hands to that dense, leafy barrier and tried to push through it. It yielded, but only a little and scratchily. The leaves were wet with dew.

She stepped back from it and looked around the night garden. All was silence and stillness. Her daughter was gone again. If she had ever really been here at all.

Sessurea was the one the tangle chose to confront Maulkin. It both angered and wounded Shreever that they had so obviously been conferring amongst themselves. If one had a doubt, why had not that one come to speak of it to Maulkin himself, rather than sharing the poisonous idea with the others? Now they were all crazed with it, as if they had partaken of tainted meat. The foolishness was most strong in Sessurea, for as he whipped himself into position to challenge Maulkin, his orange mane was already erect and toxic.

‘You lead us awry!’ he trumpeted. ‘Daily the Plenty grows shallower and warmer, and the salts of it more strange. You lead us where prey is scarce and then give us scant time to feed. I scent no other tangles, for no others have come this way. You lead us not to rebirth but to death.’

Shreever shook out her ruff, arching her neck to release her poisons. If Maulkin were attacked by the others, she vowed he would not fight alone. But Maulkin did not even erect his ruff. As lazily as weed in the tides, he wove a slow pattern in the Plenty. It carried him over and then under Sessurea, who twined his own head about in an effort to keep his gaze upon Maulkin. Before the whole tangle, he changed Sessurea’s challenge into a graceful dance in which Maulkin led.

His wisdom was as entwining as his movement when he addressed Sessurea. ‘If you scent no other tangle, it is because I follow the scent of those who passed here an age ago. But if you opened wide your gills, you would scent others, and not so far ahead of us. You fear the warmth of this Plenty, and yet you were among those who first protested when I led you from warmth to coolness. You taste the strangeness of the salts and think we have gone awry. Foolish serpent! If all were familiar, then we would be swimming back into yesterday. Follow me, and do not doubt any longer. For I lead you, not into your own familiar yesterday, but into tomorrow, and the yesterday of your ancestors. Doubt no longer, but swallow my truth!’

So close had Maulkin come to Sessurea as he wove his dance and wisdom that when he lifted his mane and released his toxins, Sessurea breathed them in. His great green eyes spun as he tasted the echo of death and the truth that hides in it. He faltered in his defence, going limp, and would have sunk to the bottom had not Maulkin wrapped his length with his own. Yet even as he bore up the one who would have denied him, the tangle cried out in unease. For above the Plenty and yet in it, and below the Lack and yet in it, a great darkness moved. Its shadow passed over them soundlessly save for the rush of its finless body.

Yet when the rest of the tangle would have fled back into the depths, Maulkin upheld Sessurea and pursued the shape. ‘Come!’ he trumpeted back to them all. ‘Follow! Follow without fear, and I promise you both food and rebirth when the time for the gathering is upon us!’

Shreever mastered her fear only with her loyalty to Maulkin. Of all the tangle, she first uncoiled herself to flow through the Plenty and follow their leader. She watched the first shivering of awareness come back to Sessurea, and marked how gently he parted himself from Maulkin. ‘I saw this,’ he called back to the others who still lagged and hesitated. ‘This is right, Maulkin is right! I have seen this in his memories, and now we live it again. Come. Come.’

At that acknowledgement, there came forth from the shape food, prey that neither struggled nor swam, but drifted down to be seized and consumed by all.

‘We shall not starve,’ Maulkin assured his followers quietly. ‘Nor shall we need to delay our journey for fishing. Set aside your doubts and reach for your deepest memories. Follow.’

AUTUMN (#ulink_f5a6046a-72be-5b33-9021-b41e1c7f08e7)

16 NEW ROLES (#ulink_8ef00627-88b2-5890-9a01-988bec9cb5db)

THE SHIP CRESTED THE WAVE, her bow rising as if she would ascend into the tortured sky itself. Sa knew, the rain was near heavy enough to float a ship. For a long hanging instant, Althea could see nothing but sky. In the next instant, they were rushing headlong down a long slope of water into a deep trough. It seemed as if they must plunge into the rising wall of water, and plunge they did, green water covering the deck. The impact jarred the mast, and with it the yard that Althea clung to. Her numbed fingers slipped on the wet cold canvas. She curled her feet about the footrope she had braced them on and made her grip more firm. Then with a shudder, the ship was shaking it off, rising through the water and rushing up the next mountain.

‘Ath! Move it!’ The voice came from below her. On the ratlines, Reller was glaring at her, eyes squinted against the wind and rain. ‘You in trouble, boy?’

‘No. I’m coming,’ she called back. She was cold and wet and incredibly tired. The other hands had finished their tasks and fled down the rigging. Althea had paused a moment to cling where she was and gather some strength for the climb down. At the beginning of her watch, at first sight of storm, the captain had ordered the sails hauled down and clewed up. The rain hit them first, followed by wind that seemed bent on picking them out of the rigging. They had no sooner finished and regained the deck than the cry came to double reef the topsails and furl everything else. In seeming response to their efforts, the storm grew worse. Her watch had clambered about the rigging like ants on floating debris, clewing down, close reefing and furling in response to order after order, until she had stopped thinking at all, only moving to obey the bellowed commands. She had not forgotten why she was there; of their own accord, her hands had packed the wet canvas and secured it. Amazing, what the body could do even when the mind was numbed by weariness and fear. Her hands and feet were like cleverly-trained animals now that contrived to keep her alive despite her own ambivalence.

She made her slow way down, the last to be clear of the rigging as always. The others had passed her on the way down and were most likely already below. That Reller had even bothered to ask her if she was in trouble marked him as far more considerate than the rest. She had no idea why the man seemed to keep an eye on her, but she felt at once grateful and humiliated by it.

When she had first joined the ship’s crew, she had been burning to distinguish herself. She had driven herself to do more, faster and better. It had seemed wonderful to be back on a deck again. Repetitious food, badly stored; crowded and smelly living conditions; even the crudity of those she was forced to call shipmates had all seemed tolerable in her first days aboard. She was back at sea, she was doing something, and at the end of the voyage she’d have a ship’s ticket to rub in Kyle’s face. She’d show him. She’d regain her ship, she promised herself, and resolutely set out to learn this new ship as swiftly as she could.

But despite her best efforts, her inexperience on such a vessel was multiplied by the lesser size of her body. This was a slaughter-ship, not a merchant-trader. The captain’s objective was not to get swiftly from one place to another to deliver goods, but to cruise a zig-zag path looking for prey. The ship carried a far larger crew than would a merchant-ship of the same size, for in addition to sailing, there must be enough hands to hunt, slaughter, render and stow the harvested meat and oil below. Hence the ship was more crowded and less clean. She had held fast to her resolution to learn fast and well, but determination alone could not make her the best sailor on this stinking carrion ship. She knew, in some dim back part of her mind, that she had vastly improved her skills and stamina since signing on to the Reaper. She also knew that what she had achieved was still not enough to make her what her father would have called ‘a smart lad’. Her purposefulness had wallowed down into despair. Then she had lost even that. Now she survived from day-to-day, and thought of little more than that.

She was one of three ‘boys’ aboard the slaughter-ship. The other two, young relatives of the captain, drew the gentler chores. They waited table for both the captain and mate, with a fair chance at getting the leavings from decent meals. They often helped the cook, too, with the lesser chores of preparing food for the main crew. She envied them that the most, she thought to herself, for it often meant they were inside, not only out of the storm’s reach but close to the heat of the cook stove. To Althea, the odd boy, fell the cruder tasks of a ship’s boy. The messy clean-ups, the hauling of buckets of slush and tar, and the make up work of any task that merited an extra man. She had never worked so hard in her life.

She held tight to the mast for a moment longer, just out of reach of yet another wave that swamped the deck. From there to the shelter of the forepeak, she moved in a series of dashes and gasping moments of clinging tight to lines and rails to stay with the vessel as she ploughed through wave after wave. They’d had three solid days of bad weather now. Before the current storm began, Althea had naively believed it would not get much worse. The experienced hands seemed to accept it as part of a normal season on the Outside. They cursed it and demanded of Sa that he end it, but always wound up telling one another tales of worse storms they had endured upon less seaworthy vessels.

‘Ath! Boy! Best get a move on if you want your share of the mess tonight, let alone to eat it while it’s got a breath of warmth in it!’

Reller’s words had more than a bit of threat to them, but despite that tone the old hand stayed on deck, watching her until she gained his side. Together they went below, sliding the hatch tight shut behind them. Althea paused on the step behind Reller to dash the water from her face and arms and then wring out the thick queue of her hair. Then she followed him down into the belly of the ship.

A few months ago, she would have said it was a cold, wet, smelly place. Now it was haven if not home, a place where the wind could not drive the rain into you so fiercely. The yellow light of a lantern was almost welcoming. She could hear food being served out, a wooden ladle clacking against the inside of a kettle, and hastened to be sure of getting her rightful share.

On board the Reaper, there were no crew quarters. Each man found himself a sleeping spot and claimed it. The more desirable ones had to be periodically defended with fists and oaths. There was a small area in the midst of the cargo hold that the men had claimed as a sort of den. Here the kettle of food was brought by one of the ship’s boys and rationed out in dollops as soon as they came off watch. There was no table, no benches to sit on, save your sea-chest if you had one. For the rest, there was only the deck and the odd keg of oil to lean against. The plates were wooden trenchers, cleaned only with a wiping of fingers or bread, when they had bread. Ship’s biscuit was the rule, and in a storm like this, there was small chance that Cook had tried to bake anything. Althea made her way through a jungle of dangling garments. Wet clothing hung everywhere from pegs and hooks in a pretence of drying. Althea shrugged out of her oilskin, won last week gambling with Oyo, and hung it on the peg she had claimed as her own.

Reller’s threat had not been idle. He was serving himself as Althea approached, and like every man on the ship, he took what he wanted with no regard for who came after. Althea snatched up an empty trencher and waited eagerly for him to be out of the way. She sensed he was taking his time about it, trying to bait her into complaint, but she had learned the hard way to be wiser than that. Anyone could cuff a ship’s boy, and they did not need the excuse of his whining to do it. Better to keep silent and get half a ladle of soup than to complain and get only a cuff for her supper. Reller crouched over the kettle and ladled up scoop after scoop from the shallow puddle of what was left. Althea swallowed and waited her turn.

When Reller saw she would not be baited, he almost smiled. Instead he told her, ‘There, lad. I’ve left you a few lumps in the bottom. Clean up the kettle, and then run it back to Cook.’

Althea knew this was a kindness, in a way. He could have taken all and left her naught but scrapings and no one would have even considered speaking against him. She was happy to take the kettle and all and retire to her claimed spot to devour it.

She had a good place, all things considered. She had wedged her meagre belongings up in a place where the curve of the hull met the deck above. It made it near impossible to stand upright. Here she had slung her hammock. No one else could have curled himself small enough to sleep comfortably there. She had found she could retreat there and be relatively undisturbed while she slept; no one was brushing past her in wet rain gear. So she took the kettle to her corner and settled down with it.

She scooped up what broth was left with her mug and drank it down. It was not hot — in fact the grease had congealed in small floating blobs — but it was warmer than the rain outside and the fat tasted good to her. True to his word, Reller had left some lumps. Potato, or turnip or perhaps just a doughy blob of something meant to be a dumpling but not cooked enough. Althea didn’t care. Her fingers scooped it up and she ate it. With a hard round of ship’s biscuit she scraped the kettle clean of every last remnant of food.

She had no sooner swallowed the last bite than a great weariness rose up in her. She was cold and wet and ached in every bone. More than anything, she longed simply to drag down her blanket, roll up in it and close her eyes. But Reller had told her she had to take the kettle back to the cook. She knew better than to wait until after she had slept. That would be seen as shirking. She thought Reller himself might turn a blind eye to it, but if he did not, or if the cook complained, she could catch the end of a rope for it. She couldn’t afford that. With a sound that could have been a whimper, she crept from her sleeping space with the kettle cradled in her arms.

She had to brave the storm-washed deck again to reach the galley. She made it in two dashes, holding onto the kettle as tightly as she held onto the ship. If she let something like that wash overboard, she knew they’d make her wish she’d gone with it. When she got to the galley, she had to kick and beat upon the door; the cook had secured it from inside. When he did let her in, it was with a scowl. Wordlessly, she offered him the kettle, and tried not to look longingly at the fire in its box behind him. If you were favoured by the cook, you could stay long enough to warm yourself. The truly privileged could hang a shirt or a pair of trousers in the galley, where they actually dried completely. Althea was not even marginally favoured. The cook gestured her out the door as soon as she set the kettle down.

On the trip back, she misjudged her timing. Later, she would blame it on the cook for turning her so swiftly out of the galley. She thought she could make it in one dash. Instead the ship seemed to dive straight into a mountain of water. She felt her desperate fingers brush the line she lunged for, but she did not make good her hold. The water simply swept her feet out from under her and rushed her on her belly across the deck. She kicked and struggled wildly, trying to claw some kind of a hold on the deck with fingers and toes. The water was in her eyes and up her nose; she could not see nor find breath to shout for help. An eternal instant later, she was slammed into the ship’s railing. She took a glancing blow to the side of her head that rang darkness before her eyes and near tore her ear off. For a brief moment, she knew nothing but to hold tight to the railing with both hands as she lay belly down on the swamped deck. Water rushed past her in its hurry to be overboard. She clung to the ship, feeling the seawater cascade past her, but unable to lift her head high enough to get a clear breath. She knew, too, that if she waited until the water was completely gone before she got to her feet, the next wave would catch her as well. If she didn’t manage to get up now, she wasn’t ever going to get up. She tried to move but her legs were jelly.

A hand grabbed the back of her shirt, hauled her choking to her knees. ‘You’re plugging the scuppers!’ someone exclaimed in disgust. She hung from his grip like a drowned kitten. There was air against her face, mixed with driving rain, but before she could take it in, she had to gag out the water in her mouth and nose. ‘Hang on!’ she heard him shout and she wrapped her legs and arms about his legs. She managed one gargly breath of air before the water hit them both.

She felt his body swing with the impact of the water and thought surely they would both be torn loose from the ship. But an instant later, as the water retreated, he struck her a cuff to the side of the head that loosened her grip on him. Suddenly he was moving across the deck, dragging her behind him, her pigtail and shirt caught together in his grip. He hauled her up a mast; as soon as her feet and hands felt the familiar rope, they clung to them and propelled her up of their own accord. The next wave that rushed over the deck went by beneath her. She gagged and then spat a quantity of seawater into it. She blew her nose into her hand and shook it clean. With her first lungful of air, she said, ‘Thank you.’

‘You stupid little deck rat! You damn near got us both killed.’ Anger and fear vied in the man’s voice.