По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

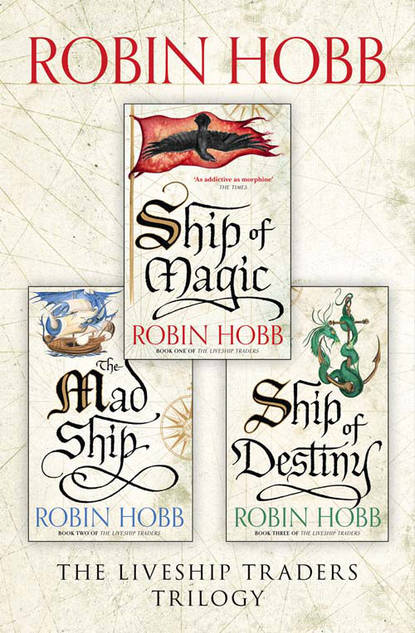

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I know. I’m sorry.’ She spoke no louder than she had to in order to be heard through the storm.

‘Sorry? I’ll make you a sight more than just sorry. I’ll kick your arse till your nose bleeds.’

He lifted his fist and Althea braced herself to take the blow. She knew that by ship’s custom she had it coming. When after a moment it did not land, she opened her eyes.

Brashen peered at her through the darkness. He looked more shaken than he had when he’d first dragged her up from the water. ‘Damn you. I didn’t even recognize you.’

She made a small gesture that could have been a shrug. Her eyes did not meet his.

Another wave made its passage across the ship. Again the ship began its wallowing climb.

‘So. How have you been doing?’ Brashen’s voice was pitched low, as if he feared to be overheard talking to her. A mate was not expected to have chummy little chats with the ship’s boy. Since discovering her, he had avoided all contact with her.

‘As you see,’ Althea said quietly. She hated this. She abruptly hated Brashen, not for anything he had done, but because he was seeing her this way. Ground down to someone less than dirt under his feet. ‘I get by. I’m surviving.’

‘I’d help you if I could.’ He sounded angry with her. ‘But you know I can’t. If I take any interest in you at all, someone will suspect. I’ve already made it plain to several of the crew that I’ve no interest in… other men.’ He suddenly sounded awkward. A part of Althea found the irony in this. Clinging to rigging on this scummy ship in the middle of a storm after he’d just offered to kick her arse, and he could not bring himself to speak of sex with her. For fear of offending her dignity. ‘On a ship like this, any kindness I showed you would be construed only one way. Then someone else would decide he fancied you, too. Once they found out you were a woman…’

‘You needn’t explain. I’m not stupid,’ Althea interrupted to stop his litany. Didn’t he know she lived aboard the scum-infested tub?

‘You’re not? Then what are you doing aboard?’ He threw the last bitter words over his shoulder before he dropped from the rigging to the deck. Agile as a cat, quick as a monkey, he made his way swiftly to the bow of the ship, leaving her clinging in the rigging and staring after him.

‘The same thing you are,’ she replied snidely to his last words. It didn’t matter that he could not hear them. The next time the water cleared the deck, she followed Brashen’s example, but with considerably less grace and skill. Moments later, she was below decks, listening to the rush of water all around her. The Reaper moved through the water like a barrel. She sighed heavily, and once more dashed the water from her face and bare arms. She wrung out her queue and shook her wet feet like a cat before padding back to her corner. Her clothing was sodden against her skin, chilling her. She changed hastily into clothing that was merely damp, then wrung out what she had had on. She shook it out, hung her shirt and trousers on a peg to drip and tugged her blanket out from its hiding-place. It was damp and smelled musty, but it was wool. Damp or not, it would hold the heat of her body. And that was the only warmth she had. She rolled herself into it and then curled up small in the darkness. So much for Reller’s kindness. It had got her half-drowned and cost her half an hour of her sleep. She closed her eyes and let go of consciousness.

But sleep betrayed her. As weary as she was, oblivion would not come to her. She tried to relax, but could not remember how to loosen the muscles in her lined brow. It was the words with Brashen, she decided. Somehow they brought the situation back to her as a whole. Often she went for days without catching so much as a glimpse of him. She wasn’t on his watch; their lives and duties seldom intersected. And when she had no reminders of what her life once had been, she could simply go from hour to hour, doing what she had to do to survive. She could give all her attention to being the ship’s boy and think no further than the next watch.

Brashen’s face, Brashen’s eyes, were crueller than any mirror. He pitied her. He could not look at her without betraying to her all that she had become, and worse, all that she had never been. Bitterest of all, perhaps, was seeing him recognize as surely as Althea herself had, that Kyle had been right. She had been her Papa’s spoiled little darling, doing no more than playing at being a sailor. She recalled with shame the pride she had taken in how swiftly she could run the rigging of the Vivacia. But her time aloft had mostly been during warm summer days, and whenever she was wearied or bored with the tasks of it, she could simply come down and find something else to amuse herself. Spending an hour or two splicing and sewing was not the same as six hours of frantically hasty sailwork after a piece of canvas had split and needed to be immediately replaced. Her mother had fretted over her callouses and rough hands; now her palms were as hardened and thick-skinned as the soles of her feet had been; and the soles of her feet were cracked and black.

That, she decided, was the worst aspect of her life. Finding out that she was no more than adequate as a sailor. No matter how tough she got, she was simply not as strong as the larger men on the ship. She had passed herself off as a fourteen-year-old boy to get this position aboard the Reaper. Even if she had wished to stay with this slaughter-tub, in a year or so they were bound to notice she wasn’t growing any larger or stronger. They wouldn’t keep her on. She’d wind up in some foreign port with no prospects at all.

She stared up into the darkness. At the end of this voyage, she had planned to ask for a ship’s ticket. She still would, and she’d probably get it. But she wondered now if it would be enough. Oh, it would be the endorsement of a captain, and perhaps she could use it to make Kyle live up to his thoughtless oath. But she feared it would be a hollow triumph. Having a stamped bit of leather to show she had survived this voyage was not what she had wanted. She had wanted to vindicate herself, to prove to all, not just Kyle, that she was good at her chosen life, a worthy captain to say nothing of being a competent sailor. Now, in the brief times when she did think about it, it seemed to her that she had only proved the opposite to herself. What had seemed daring and bold when she’d begun it back in Bingtown now seemed merely childish and stupid. She’d run away to sea, dressed as a boy, taking the first position that was offered to her.

Why, she asked herself now. Why? Why hadn’t she gone to one of the other liveships and asked to be taken on as a hand? Would they have refused as Brashen had said they would? Or could she, even now, be sleeping aboard a merchant vessel cruising down the Inside Passage, sure of both wages and recommendation at the end of the voyage? Why had it seemed so important to her that she be hired anonymously, that she prove herself worthy without either her name or her father’s reputation to fall back on? It had seemed such a spirited thing to do, on those summer evenings in Bingtown when she had sat cross-legged in the back room of Amber’s store and sewed her ship’s trousers. Now it merely seemed childish.

Amber had helped her. But for her help, with both needlework and readily shared meals, Althea would never have been able to do it. Amber’s sudden befriending of her had always puzzled Althea. Now it seemed to her that perhaps Amber had actually been intent on propelling her into danger. Her fingers crept up to touch the serpent’s egg bead that she wore on a single strand of leather about her neck. The touch of it almost warmed her fingers and she shook her head at the darkness. No. Amber had been her friend, one of the few rare women-friends she’d ever had. She’d taken her in for the days of high summer, helped her cut and sew her boy’s clothing. More, Amber had donned man’s clothing herself, and schooled Althea in how to move and walk and sit as if she were male. She had, she told Althea, once been an actress in a small company. Hence she’d played many roles, as both sexes.

‘Bring your voice from here,’ she’d instructed her, prodding Althea below her ribs. ‘If you have to talk. But speak as little as you can. You’ll be less likely to betray yourself, and you’ll be better accepted. A good listener of any sex is rare. Be one, and it will make up for anything else perceived as a fault.’ Amber had also shown her how to wrap her breasts flat to her chest in such a way that the binding cloth appeared to be no more than another shirt worn under her outer shirt. Amber had shown her how to fold dark-coloured stockings to use as blood rags. ‘Dirty socks you can always explain,’ Amber had told her. ‘Cultivate a fastidious personality. Wash your clothing twice as much as anyone else does, and no one will question it after a time. And learn to need less sleep. For you will either have to rise before any others or stay up later in order to keep the privacy of your body. And this I caution you most of all. Trust no one with your secret. It is not a secret a man can keep. If one man aboard the ship knows you are a woman, then they all will.’

This was the only area in which Amber had, perhaps, been mistaken. For Brashen knew she was a woman, and he had not betrayed her. At least, he hadn’t so far. A sudden irony came to Althea. She grinned bitterly to herself. In my own way I took your advice, Brashen. I arranged to be reborn as a boy, and not one called Vestrit.

Brashen lay on his bunk and studied the wall opposite him. It was not far from his face. Was a time, he thought ruefully, when I would have scorned this cabin as a clothes-closet. Now he knew what a luxury even a tiny space to himself could be. True, there was scarce room to turn around once a man was inside, but he did have his own berth, and no one slept in it but him. There were pegs for his clothing, and a corner just large enough to hold his sea-chest. In the bunk, he could brace himself against the ledge that confined his body and almost sleep secure when he was off watch. The captain’s and the mate’s cabins were substantially larger and better appointed, even on a tub like this. But then on many ships the second mate had no better quarters than the crew. He was grateful for this tiny corner of quiet, even if it had come to him by the deaths of three men.

He had shipped as an ordinary seaman, and spent the first part of his trip growling and elbowing in the forecastle with the rest of his watch. Early on, he had realized he had not only more experience but a stronger drive to do his job well than the rest of his fellows. The Reaper was a slaughter-ship out of Candletown far to the south, on the northern border of Jamaillia. When the ship had left the town many months ago in spring, it had left with a mostly conscripted crew. A handful of professional sailors were the backbone of the crew, charged with battering the newcomers into shape as sailors. Some were debtors, their work sold by their creditors as a means of forcing them to pay back what they owed. Others were simple criminals purchased from the Satrap’s jails. Those who had been pickpockets and thieves had soon learned better or perished; the close quarters aboard a slaughter-ship did not encourage a man to be tolerant of such vice in his fellows. It was not a crew that worked with a will, nor one whose members were likely to survive the rigours of the trip. By the time the Reaper reached Bingtown, she’d lost a third of her crew to sickness, accidents and violence aboard. The two thirds that remained were survivors; they’d learned to sail, they’d learned to pursue the slow-moving turtles and the so-called brack-whales of the southern coast inlets and lagoons. Their services were not, of course, to be confused with the skills of the professional hunters and skinners who rode the ship in the comparative comfort of a dry chamber and idleness. The dozen or so men of that ilk never set a hand to a line or stood a watch; they idled until their time of slaughter and blood. Then they worked with a fury, sometimes going without sleep for days at a time while the reaping was good. But they were not sailors and they were not crew. They would not lose their lives save that the whole ship went down or one of their prey turned on them successfully.

The ship had beat her way north on the outside of the pirate islands, hunting, slaughtering and rendering all the way. At Bingtown, the Reaper had put in to take on clean water and supplies and to make such repairs as they had the coin to pay for. The mate had also actively recruited more crew, for the journey out to the Barren Islands. It had been nearly the only ship in the harbour that was hiring.

The storms between Bingtown and the Barrens were as notorious as the multitude of sea mammals that swarmed there just prior to the winter migration. They’d be fat with the summer feedings, the sleek coats of the young ones large enough to be worth the skinning and unscarred from battles for mates or food. It was worth braving the storms of autumn to take such prizes — soft furs, the thick layer of fat, and beneath it all the lean, dark-red flesh that tasted both of sea and land. The casks of salt that had filled the hold when they left Candletown would soon be packed instead with salted slabs of the prized meat, with hogsheads of the fine rendered oil, while the scraped hides would be packed with salt and rolled thick to await tanning. It would be a cargo rich enough to make the Reaper’s owners dance with glee, while those debtors who survived to reach Candletown again would emerge from their ordeal as free men. The hunters and skinners would claim a percentage of the total take and begin to take bids on their services for the next season based on how well they had done this time. As for the true sailors who had taken the ship all that way and brought her back safely, they would have a pocketful of coins to jingle, enough to keep them in drink and women until it was time to sail again for the Barrens.

A good life, Brashen thought wryly. Such a fine berth as he had won for himself. It had not taken much. All he had had to do was scramble swiftly enough to catch the mate’s eye and then the captain’s. That, and the vicious storm that had carried off two men and crippled the third who was a likely candidate for this berth.

Yet it was not any peculiar guilt at having stepped over dead men to claim this place and the responsibilities that went with it that bothered him tonight. No. It was the thought of Althea Vestrit, his benefactor’s daughter, curled in wet misery in the hold in the close company of such men as festered there. ‘There’s nothing I can do about it.’ He spoke the words aloud, as if by giving them to air he could make them ease his conscience. He hadn’t seen her come aboard in Bingtown; even if he had, he wouldn’t have recognized her easily. She was a convincing mimic as a sailor lad; he had to give her that.

His first hint that she was aboard had not been the sight of her. He’d glimpsed her any number of times as ‘a ship’s boy’ and given no thought to it. Her flat cap pulled low on her brow and her boy’s clothes had been more than sufficient disguise. The first time he’d seen a rope secured to the hook on a block with a double blackwall hitch rather than a bowline, he’d raised an eyebrow. It was not that rare a knot, but the bowline was the common preference. Captain Vestrit, however, had always preferred the blackwall. Brashen hadn’t given much thought to it at the time. A day or so later, coming out on deck before his watch, he’d heard a familiar whistle from up in the rigging. He’d looked up to where she was waving at the lookout, trying to catch his attention for some message, and instantly recognized her. ‘Oh, Althea,’ he’d thought to himself calmly, and then started an instant later as his mind registered the information. In disbelief, he’d stared up at her, mouth half-agape. It was her: no mistaking her style of running along the footropes. She’d glanced down, and at sight of him had so swiftly averted her face that he knew she’d been expecting and dreading this moment.

He’d found an excuse to linger at the base of the mast until she came down. She’d passed him less than an arm’s length away, with only one pleading glance. He’d clenched his teeth and said nothing to her, nor had he spoken to her since then until tonight. Once he had recognized her, he’d known the dread of certainty. She wouldn’t survive the voyage. Day by day, he’d waited for her to somehow betray herself as a woman, or make the one small error that would let the sea take her life. It had seemed to him simply a matter of time. The best he had been able to hope for her was that her death would be swift.

Now it appeared that would not be the case. He allowed himself a small, rueful smile, The girl could scramble. Oh, she hadn’t the muscle to do the work she was given. Well, at least not as fast as the ship’s first mate expected such work to be done. It wasn’t, he reflected, so much a matter of muscle and weight that she lacked; she could do the work well enough, actually, save that the men she worked alongside overmatched her. Even a few inches of extra reach, a half-stone of extra weight to fling against a block-and-tackle’s task could make all the difference. She was like a horse teamed with oxen; it wasn’t that she was incapable of the work, only that she was mismatched.

Additionally, she had come from a liveship — her family liveship, at that — to one of mere wood. Had Althea even guessed that pitting one’s strength against dead wood could be so much harder than working a willing ship? Even if the Vivacia hadn’t been quickened in his years aboard her, Brashen had known from the very first time he touched a line of her that there was some underlying awareness there. The Vivacia was far from sailing herself, but it had always seemed to him that the stupid incidents that always occurred aboard other ships didn’t happen on her. On a tub like the Reaper, work stair-stepped. What looked like a simple job, replacing a hinge for instance, turned into a major effort once one had revealed that the faulty hinge had been set in wood that was half-rotten and out of alignment as well. Nothing, he sighed to himself, was ever simple on board the Reaper.

As if in answer to the thought, he heard the sharp rap of knuckles against his door. It wasn’t his watch so that could only mean trouble. ‘I’m up,’ he assured his caller. In an instant he was on his feet and had the door opened. But this was not the mate come to call him to extra duties on this stormy night. Instead Reller stepped in hesitantly. Water still streamed down his face and dripped from his hair.

‘Well?’ Brashen demanded.

A frown divided the man’s wide brow. ‘Shoulder’s paining me some,’ he offered.

Brashen’s duties included minding the ship’s medical supplies. They’d started the voyage with a ship’s doctor he’d been told, but had lost him overboard one wild night. Once it had been discovered that Brashen could read the spidery letters that labelled the various bottles and boxes of medicines, he’d been put in charge of what remained of the medical stores. He personally doubted the efficacy of many of them, but passed them out according to the labels’ instructions.

So now he turned to the locked chest that occupied almost as much space as his own sea-chest did and groped inside his shirt for the key that hung about his neck. He unlocked the chest, frowned into it for a moment, and then took out a brown bottle with a fanciful green label on it. He squinted at the writing in the lantern’s unsteady light. ‘I think this is what I gave you last time,’ he guessed aloud, and held the bottle up for Reller’s inspection.

The sailor peered at it as if a long stare would make the letters intelligible to him. At last he shrugged. ‘Label was green like that,’ he allowed. ‘That’s probably it.’

Brashen worked the fat cork loose from the thick neck and shook out onto his palm half a dozen greenish pellets. They looked, he thought to himself, rather like a deer’s droppings. He’d have only been mildly surprised to discover that’s what they actually were. He returned three to the bottle and offered the other three to Reller. ‘Take them all. Tell Cook I said to give you a half-measure of rum to wash those down, and to let you sit in the galley and stay warm until they start working.’

The man’s face brightened immediately. Captain Sichel was not free with the spirits aboard ship. It would probably be the first taste he’d had since they’d left Bingtown. The prospect of a drink, and a warm place to sit for a time made the man’s face glow with gratitude. Brashen knew a moment’s doubt but then reflected that he had no idea how well the pellets would work; at least he could be sure that the rough rum they bought for the crew would help the man to sleep past his pain.

As Reller was turning to leave, Brashen forced himself to ask his question. ‘My cousin’s boy… the one I asked you to keep an eye on. How’s he working out?’

Reller shrugged. He jiggled the three pellets loosely in his left hand. ‘Oh, he’s doing fine, sir, just fine. He’s a willing lad.’ He set his hand to the latch, clearly eager to be gone. The promised rum was beckoning him.

‘So,’ Brashen went on in spite of himself. ‘He knows his job and does it smartly?’

‘Oh, that he does, that he does, sir. A good lad, as I said. I’ll keep an eye on Athel and see he comes to no harm.’

‘Good. Good, then. My cousin will be proud of him.’ He hesitated. ‘Mind, now, don’t let the boy know any of this. Don’t want him to think he’ll get any special treatment.’

‘Yes sir. No sir. Goodnight, sir.’ And Reller was gone, shutting the door firmly behind him.

Brashen shut his eyes and took a deep breath. It was as much as he could do for Althea, asking a reliable man like Reller to keep an eye on her. He checked to make sure the catch on his door was secure, and then re-locked the cabinet that held the medical supplies. He crawled back into the narrow confines of his bunk and heaved a heavy sigh. It was as much as he could do for Althea. Truly, it was. It was.

Eventually, he was able to fall asleep.

Wintrow didn’t like the rigging. He had done his best to conceal that from Torg, but the man had a bully’s unerring instinct. As a result, a dozen times a day he would fabricate a reason why Wintrow had to climb the mast. When he had sensed the repetition was dulling Wintrow’s trepidation, he had added to the task, giving him things to carry aloft and place in the crow’s nest, only to send him to fetch them back down almost as soon as he’d regained the deck. Torg’s latest commands had him not only climbing the rigging, but going out to the ends of the spars and clinging there, heart in his mouth, waiting for Torg’s shouted command to return. It was simple hazing, of the stupidest, most predictable sort. Wintrow expected such from Torg. It had been harder to comprehend that the rest of the crew accepted his torment as normal. When they paid any attention at all to what Torg was subjecting him to, it was usually with amusement. No one intervened.

And yet, Wintrow reflected as he clung to a spar and looked down at the deck so far below him, the man had actually done him a favour. The wind rushed past him, the canvas was full-bellied with it, and the line he perched on sang with the tension. The height of the mast exaggerated the ship’s motion through the water, amplifying every roll into an arc. He still did not like being up there, but he could not deny there was an exhilaration to being there that had nothing to do with enjoyment. He had met a challenge and bested it. Left to himself, he would never have sought to take his own measure in this way. He squinted his eyes to the wind that rushed past his ears deafeningly. For a moment he toyed with the idea that perhaps he did belong here, that maybe deep within the priest there could be the heart of a sailor.

A small, odd noise came to his ears. A vibration of metal. He wondered if it were some fitting about to give way, and his heart began to beat a bit faster. Slowly he worked his way along the ratline, looking for the source of the sound. The wind mocked him, bringing the sound and then blasting it away. He had heard it a few times before he recognized that there were variations in tone and a rhythm to the sound that defied the steady rush of the wind. He got to the crow’s nest and clung to the side.

Within the lookout’s post was Mild. The sailor had folded himself up into a comfortable braced squat. His eyes were closed to slits, a tiny jaw harp braced against his cheek. He played it one-handed, the sailor’s way, using his own mouth as a sounding box as his fingers danced on the metal prongs that were the keys. His ears were turned to his private music as his eyes scanned the horizon.