По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

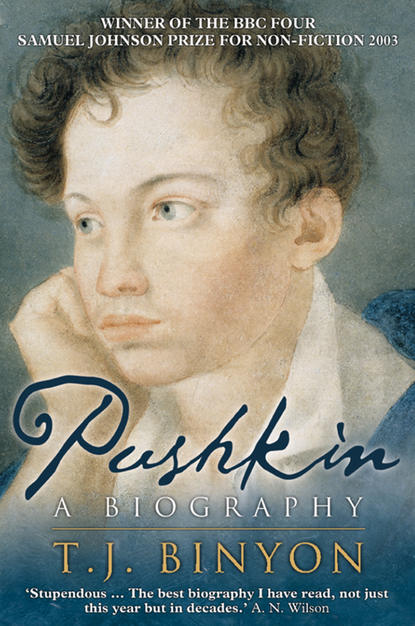

Pushkin

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

â (#ulink_779ad34d-3019-5a6a-80ac-c0520059e57e) The quatrain is listed under Dubia in the Academy edition; its ascription to Pushkin is based on an army report of the interrogation of Private (demoted from captain) D. Brandt, who, on 18 July 1827, deposed that his fellow-inmate in the Moscow lunatic asylum, Cadet V.Ya. Zubov, had declaimed this fragment of Pushkin to him (II, 1199â200).

* (#ulink_4bf7ebe9-4864-594b-a479-910bd8b388fc) Pushkin is comparing himself to St John; earlier in the letter he refers to Kishinev as Patmos, the island to which the apostle was exiled by the Emperor Domitian, and where he is supposed to have written the Book of Revelation, the Apocalypse.

* (#ulink_4b2625d5-2b2f-5e83-a645-c1e159297de1) It was first printed in London in 1861; the first Russian edition â with some omissions â appeared in 1907.

* (#ulink_e8391ed9-76d1-5184-9f2f-bbb6259656cd) A system for mass education devised by the Englishman Joseph Lancaster (1778â1838), by which the advanced pupils taught the beginners.

* (#ulink_fed2b239-f5df-5041-9097-d92e4c2a2d4c) Formerly proprietor of the Hotel de lâEurope, a luxurious establishment situated at the bottom of the Nevsky Prospect, he took to drink, got into financial difficulty and was ruined when his wife absconded with his cash-box and a colonel of cuirassiers. He fled to Odessa and, after various vicissitudes, ended up in Kishinev.

* (#ulink_a1a0b4d0-e380-58a5-98ac-f2971e226a51) Pushkin often uses the word âoccasionâ (Russian okaziya, borrowed from the French occasion) to mean the opportunity to have a letter conveyed privately, by a friend or acquaintance, instead of entrusting it to the post, when it might be opened and read. Here the âdependable occasionâ is a trip by Liprandi to St Petersburg.

â (#ulink_a1a0b4d0-e380-58a5-98ac-f2971e226a51) âLittle book (I donât begrudge it), you will go to the city without me,/Alas for me, your master, who is not allowed to go.â

* âI fear the Greeks [though they bear gifts]â. Virgil, Aeneid, II, 49. The quotation had especial relevance to Gnedich: he was âGreekâ because he was in the process of translating the Iliad.

* (#ulink_e5e2b716-beeb-5d44-b16c-b0e2112dfc87) Vyazemskyâs enthusiastic article on the poem had appeared in Son of the Fatherland in 1822.

* The nickname often given to Pushkin in the correspondence between Turgenev and Vyazemsky: a pun on bes arabsky, âArabian devilâ, and bessarabsky, âBessarabianâ.

* (#ulink_c229a29e-afed-58e5-8ff2-a2e2cac6990c) The last two sentences are a quotation from Zhukovskyâs translation of The Prisoner of Chillon. The original reads: âAnd I felt troubled â and would fain/I had not left my recent chainâ (357â8).

8 ODESSA 1823â24 (#ulink_5cf3e488-7935-5054-8a6c-e78abcd413d0)

I lived then in dusty Odessa â¦

There the skies long remain clear,

There abundant trade

Busily hoists its sails;

There everything breathes, diffuses Europe,

Glitters of the South and is gay

With lively variety.

The language of golden Italy

Resounds along the merry street,

Where walk the proud Slav,

The Frenchman, the Spaniard, the Armenian,

And the Greek, and the heavy Moldavian,

And that son of the Egyptian soil,

The retired corsair, Morali.

Fragments from Oneginâs Journey

IN 1791 THE TREATY OF JASSY, which brought the Russo â Turkish war to an end, gave Russia what its rulers had sought since the late seventeenth century: a firm footing on the Black Sea littoral. To exploit this a harbour was needed; those in the Sea of Azov and on the river deltas were too shallow for large vessels, and attention was turned to the site of the Turkish settlement of Khadzhibei, between the Bug and Dniester, where the water was deep close inshore, and which, with the construction of a mole and breakwater, would be safe in any weather. Here, where the steppe abruptly terminated in a promontory, some 200 feet above the coastal plain, the construction of a new city began on 22 August 1794. Its name, Odessa, came from that of a former Greek settlement some miles to the east, but was, apparently on the orders of the Empress Catherine herself, given a feminine form. The cityâs architect and first governor was Don Joseph de Ribas, a soldier of fortune in Russian service, born in Naples of Spanish and Irish parentage. With the assistance of a Dutch engineer, he laid out a gridiron plan of wide streets and began construction of a mole.

Under Richelieu, governor from 1803 to 1815 â whose little palazzo in Gurzuf had sheltered Pushkin and the Raevskys â the city prospered and gained in amenities: a wide boulevard was constructed along the cliff edge, overlooking the sea; and âan elegant stone theatre, [â¦] the front of which is ornamented by a peristyle supported by columnsâ,

(#litres_trial_promo) was built. It was usually occupied by an Italian opera company: Pushkin became addicted to âthe ravishing Rossini,/Darling of Europeâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) However, the town âwas still in the course of construction, there were everywhere vacant lots and shacks. Stone houses were scattered along the Rishelevskaya, Khersonskaya and Tiraspolskaya streets, the cathedral and theatre squares; but for the most part all these houses stood in isolation with wooden single-storey houses and fences between them.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Very few streets were paved: all travellers mention the insupportable dust in the summer, and the indescribable mud in the spring and autumn.

In 1819 Odessa had become a free port: the population increased â there were some 30,000 inhabitants in 1823 â as did the number of foreign merchants and shipping firms. The lingua franca of business was Italian, and many of the streets bore signs in this language or in French, until Vorontsov, in a fit of patriotism, had them replaced by Russian ones. But this could not conceal the fact that the city was very different in its population and its manners from the typical Russian provincial town: âTwo customs of social life gave Odessa the air of a foreign town: in the theatre during the entrâactes the men in the parterre audience would don their hats, and the smoking of cigars on the street was allowed.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Odessa, with its opera and its restaurants, might seem a far more attractive place for exile than Kishinev. Nevertheless, Pushkin was to be considerably less happy here. He had lost the company of his close friends: Gorchakovâs regiment was still stationed in Kishinev; Alekseev, not wishing to part from his mistress Mariya Eichfeldt, had turned down a post he had been offered with Vorontsov in Odessa; while Liprandi, who had left the army and was attached to Vorontsovâs office, was rarely in Odessa, being continually employed on missions elsewhere. And though Aleksandr Raevsky was now living in the town, the relationship between the two was to become very strained over the following months. Pushkin did make a number of new acquaintances, but they remained acquaintances, rather than friends. He was closest, perhaps, to Vasily Tumansky, a year younger than himself, an official in Vorontsovâs bureau and a fellow-poet â âOdessa in sonorous verses/Our friend Tumansky has described.â

(#litres_trial_promo) But he had no great opinion of his talent: âTumansky is a famous fellow, but I do not like him as a poet. May God give him wisdom,â he told Bestuzhev.

(#litres_trial_promo) He found, too, Tumanskyâs hyperbolic praise â calling him âthe Jesus Christ of our poetryâ

(#litres_trial_promo) â and servile imitation of his work distasteful. However, they dined together most evenings in Dimitrakiâs Greek restaurant, sitting with others over wine until the early hours. An acquaintance of a different kind was âthe retired corsair Moraliâ,

(#litres_trial_promo) a Moor from Tunis, and the skipper of a trading vessel â âa very merry character, about thirty-five years old, of medium height, thick-set, with a bronzed, somewhat pock-marked, but very pleasant physiognomyâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) He spoke fluent Italian, some French, and was very fond of Pushkin, whom he accompanied about the town. Some believed that he was a Turkish spy. Pushkin struck up an acquaintance, too, with the Vorontsovsâ family doctor, the thirty-year-old William Hutchinson, whom they had engaged in London in the autumn of 1821. Tall, thin and balding, Hutchinson proved to be an interesting companion, despite his deafness, taciturnity and bad French. The vicissitudes of his emotional life, however, contributed most to his unhappiness. In Kishinev he may have believed himself several times to be in love, but these light and airy flirtations bore no resemblance to the serious and deep involvements he was now to experience. And whereas Inzov had shown a paternal affection towards him, indulgently pardoning Pushkinâs misdemeanours, or, if this was impossible, treating him like an erring adolescent, his relationship with Vorontsov, far more of a grandee than his predecessor, was of a very different kind.

In 1823 Count Mikhail Vorontsov was forty-one. He was the son of the former Russian ambassador in London, who had married into the Sidney family and settled in England permanently after his retirement. Vorontsov had received an English education, had studied at Cambridge, and was, like his father, a convinced Anglophile. His sister, Ekaterina, had married Lord Pembroke in 1808, and English relatives would occasionally visit Odessa. A professional soldier, Vorontsov had fought throughout the Napoleonic wars, being wounded at Borodino, and at Craonne in March 1814 had led the Russian corps that took on Napoleon himself in one of the bloodiest battles of the war. After Waterloo he commanded the Russian Army of Occupation in France, when Aleksandr Raevsky was one of his aides-de-camp. He was extremely wealthy, and had added to his fortune by marrying, in 1819, Elizaveta Branicka, who brought with her an enormous dowry: her mother, Countess Branicka, whose estate was at Belaya Tserkov, just south of Kiev, was one of the richest landowners in Russia. Before taking up his new appointment, he had invested massively in land in New Russia, buying immense estates near Odessa and Taganrog, and in the Crimea. He was âtall and thin, with remarkably noble features, as though they had been carved with a chisel, his gaze was unusually calm, and about his thin long lips there eternally played an affectionate and crafty smileâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) âPerhaps only Alexander could be more charming, when he wanted to please,â remarked Wiegel. âHe had a certain exquisite gaucheness, the result of his English upbringing, a manly reserve and a voice which, while never losing its firmness, was remarkably tender.â

(#litres_trial_promo) As a commander he had, like Orlov, discouraged brutality and cruelty in enforcing discipline and had set up regimental schools to educate the troops. He was close to a number of the future Decembrists, and had even, together with Nikolay Turgenev, Pushkinâs St Petersburg friend and fellow-Arzamasite, attempted to set up a society of noblemen with the aim of gradually emancipating the serfs. He had thus acquired the reputation of a liberal; a reputation which he was now strenuously attempting to live down, given the current climate in government circles: a mixture of mysticism and reaction, combined with â since the mutiny of the Semenovsky Life Guards in 1820 â paranoid suspicion of anything remotely radical.

When, at the beginning of August, Pushkin returned to Odessa in Vorontsovâs suite, he took a room in the Hotel Rainaud, where he lived throughout his stay. The hotel was on the corner of Deribasovskaya and Rishelevskaya Streets (named after the first two governors, de Ribas and Richelieu); behind it an annexe, which fronted on Theatre Square, housed the Casino de Commerce, or assembly-rooms: âThe great oval hall, which is surrounded by a gallery, supported on numerous columns, is used for the double purpose of ballroom, and an Exchange, where the merchants sometimes transact their affairs,â wrote Robert Lyall, who visited Odessa in May 1822.

(#litres_trial_promo) Baron Rainaud, the owner of the hotel and casino, was a French émigré; he also possessed a charming villa on the coast three miles to the east of the city, with wonderful views over the Black Sea. Vorontsov rented it for his wife, who was in the final stages of pregnancy when she arrived from Belaya Tserkov on 6 September: she gave birth to a son two months later.

Pushkin had a corner room on the first floor with a balcony, which gave a view of the sea. The theatre and casino were two minutes away; five minutesâ walk down Deribasovskaya and Khersonskaya Streets took him to César Automneâs restaurant, the best in town â

What of the oysters? theyâre here! O joy!

Gluttonous youth flies

To swallow from their sea shells

The plump, living hermitesses,