По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

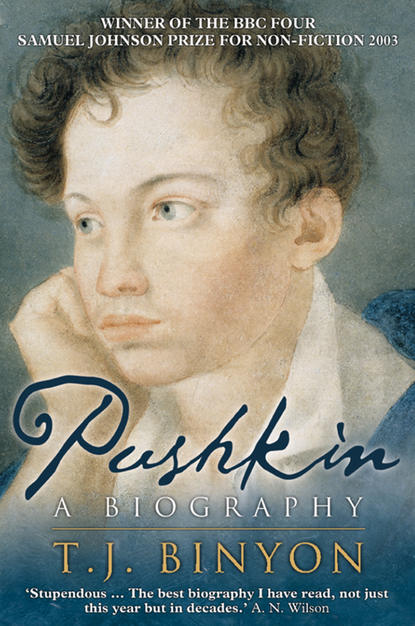

Pushkin

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Five days later the lycéens read Kutuzovâs dispatch from Borodino in the Northern Post. As they were cheering the news, the victorious Russian army was passing through Moscow and retreating to the southeast, towards Ryazan. Alexander learnt of this on 7 September. Rumour of the retreat quickly spread through St Petersburg, causing an abrupt change of mood. Napoleon now stood between the capital and the main Russian army. Only Wittgensteinâs weak First Corps protected the city; if Napoleon turned north, an evacuation would be necessary. Government archives and the pictures in the Hermitage were packed up; plans were made for removing the statues of Peter the Great and Suvorov; many of the books of the imperial public library were crated and sent up the Neva.

(#ulink_171409b6-f804-594b-92e3-f59e933b9fbd) And Razumovsky wrote to Malinovsky, telling him that the Lycée, like the court, would be evacuated to à bo (Turku) in Finland, and asking him to supply a list of necessities for the move. When Malinovsky did so, the minister objected that tin plates and cups for travelling were not essential and that trunks for the pupilsâ clothes could be replaced by wooden crates. He added that the items should be bought only on the condition that a refund would be made, should they not be required.

Napoleon entered Moscow on 2 September. Fires broke out that night and the night after, apparently lit on the orders of the Governor-General of Moscow, Count Fedor Rostopchin. The city burned for four days. Pushkinâs uncle lost his house, his library and all his possessions, and â one of the last to leave â arrived in Nizhny Novgorod with no money and only the clothes he stood up in. The Grande Armée left Moscow on 7 October, and after a bloody battle at Maloyaroslavets, which both sides again claimed as a victory, was forced back on its old line of march, losing stragglers to cold, hunger, illness and Davydovâs partisans each day. News of Maloyaroslavets and of General Wintzingerodeâs entry into Moscow reached the Lycée simultaneously. The fear of evacuation was past, and with the French on the retreat normal life could be resumed. Pushkin called Gorchakov a âpromiscuous Polish madamâ; insulted Myasoedov with some unrepeatable verses about the Fourth Department, in which the latterâs father worked (since the Fourth Department of the Imperial Chancery administered the charitable foundations and girlsâ schools of the dowager empress, a guess can be made at the nature of the insult); and pushed Pushchin and Myasoedov, saying that if they complained they would get the blame, because he always managed to wriggle out of it.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On 4 January 1813 the Northern Post reported the reading in St Petersburgâs Kazan Cathedral of the imperial manifesto announcing the end of the Fatherland War: the last of Napoleonâs troops had recrossed the Neman. Napoleon, however, was not yet beaten. Fighting continued throughout that year, with Austria, Prussia and Russia in alliance. Alexander was determined to avenge the fall of Moscow with the surrender of Paris, but it was not until 31 March 1814 (NS) that he entered the city and was received by Talleyrand. The news reached St Petersburg three weeks later, and Koshansky immediately gave his pupils âThe Capitulation of Parisâ as a theme for prose and poetic composition.

If Pushkin produced a composition on this occasion, it has not survived. However, when in November 1815 Alexander returned from the peace negotiations in Paris that followed Waterloo, Pushkin was asked by I.I. Martynov, the director of the department of education, to compose a piece commemorating the occasion. He completed the poem by 28 November, and sent it to Martynov, writing, âIf the feelings of love and gratitude towards our great monarch, which I have described, are not too unworthy of my exalted subject, how happy I would be, if his excellency Count Aleksey Kirilovich [Razumovsky] were to deign to put before his majesty this feeble composition of an inexperienced poet!â

(#litres_trial_promo) The poem, written in the high, solemn style that befits the subject, begins with an account of the French invasion and ensuing battles â in which, Pushkin laments, he was unable to participate, âgrasping a sword in my childish handâ â before describing the liberation of Europe and celebrating Alexanderâs return to Russia. It ends with a vision of the idyllic future, when

a golden age of tranquillity will come,

Rust will cover the helms, and the tempered arrows,

Hidden in quivers, will forget their flight,

The happy villager, untroubled by stormy disaster,

Will drag across the field a plough sharpened by peace;

Flying vessels, winged by trade,

Will cut the free ocean with their keels;

and, occasionally, before âthe young sons of the martial Slavsâ, an old man will trace plans of battle in the dust with his crutch, and

With simple, free words of truth will bring to life

In his tales the glory of past years

And will, in tears, bless the good tsar.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Pushkins had decided not to return to Moscow, four-fifths of which had been destroyed by the fire of 1812, but to move to St Petersburg. Nadezhda, with her surviving children, Olga and Lev (Mikhail, born in October 1811, had died the following year), arrived in the capital in the spring of 1814, and rented lodgings on the Fontanka, by the Kalinkin Bridge, in the house of Vice-Admiral Klokachev. When she and the children drove out to visit Pushkin at the beginning of April, it was the first time for more than two years that he had seen his mother, and nearly three years since he had last seen his brother and sister. Lev became a boarder at the Lycée preparatory school, and from now on Nadezhda, usually accompanied by Olga, came to Tsarskoe Selo almost every Sunday. In the autumn the family circle was completed by the arrival of Sergey, after a leisurely journey from Warsaw. His first visit to his sons was on 11 October. In the final school year Engelhardt relaxed the regulations and allowed lycéens whose families lived nearby to visit them at Christmas 1816 and at Easter 1817. Pushkin spent both holidays with his family.

âI began to write from the age of thirteen,â Pushkin once wrote.

(#litres_trial_promo) The first known Lycée poem was written in the summer of 1813. From then on the school years were, in Goetheâs words, a time âDa sich ein Quell gedrängter Lieder/Ununterbrochen neu gebarâ.

(#ulink_281d5db6-1d43-5380-9601-3684d50acd5b) Impromptu verse sprang into being almost without conscious thought: Pushchin, recuperating in the sickbay, woke to find a quatrain scrawled on the board above his head:

Here lies a sick student â

His fate is inexorable!

Away with the medicine:

Loveâs disease is incurable!

(#litres_trial_promo)

Semen Esakov, walking one winterâs day in the park with Pushkin, was suddenly addressed:

Weâre left with the question

On the frozen watersâ bank:

âWill red-nosed Mademoiselle Schräder

Bring the sweet Velho girls here?â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Like other lycéens, the two were ardent admirers of Sophie and Josephine, the banker Joseph Velhoâs two beautiful daughters, whom they often met at the house of Velhoâs brother-in-law, Ludwig-Wilhelm Tepper de Ferguson, the Lycéeâs music teacher. Sophie was unattainable, however: she was Alexander Iâs mistress, and would meet him in the little, castle-like Babolovsky Palace, hidden in the depths of the park.

Beauty! Though ecstasy be enjoyed

In your arms by the Russian demi-god,

What comparison to your lot?

The whole world at his feet â here he at yours.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Not wishing to be outdone by Delvig, Pushkin sent one of his poems â âTo My Friend the Poetâ, addressed to Küchelbecker â anonymously to the Herald of Europe in March 1814. The next number of the journal contained a note from the editor, V.V. Izmailov, asking for the authorâs name, but promising not to reveal it. Pushkin complied with the request, and the poem, his first published piece, appeared in the journal in July over the signature Aleksandr N.k.sh.p.: âPushkinâ written backwards with the vowels omitted. While at the Lycée he was to publish four other poems in the Herald of Europe, five in the Northern Observer, one in the Son of the Fatherland, and eighteen in a new journal, the Russian Musaeum, or Journal of European News. The only poem published during the Lycée years without a pseudonym was âRecollections in Tsarskoe Seloâ, which appeared in the Russian Musaeum in April 1815 accompanied by an editorial note: âFor the conveyance of this gift we sincerely thank the relatives of this young poet, whose talent promises so much.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Pushkin wrote this poem at the end of 1814, on a theme given to him by the classics teacher, Aleksandr Galich, for recital at the examination at the end of the junior course. Listing the memorials to Catherineâs victories in the Tsarskoe Selo park, he apostrophizes the glories of her age, hymned by Derzhavin, before describing the 1812 campaign and capitulation of Paris and paying a graceful tribute to Alexander the peace-maker, âworthy grandson of Catherineâ. In the final stanza he turns to Zhukovsky, whose famous patriotic poem, âA Bard in the Camp of Russian Warriorsâ, had been written immediately after the battle of Borodino, and calls upon him to follow this work with a paean to the recent victory:

Strike the gold harp!

So that again the harmonious voice may honour the Hero,

And the vibrant strings suffuse our hearts with fire,

And the young Warrior be impassioned and thrilled

By the verse of the martial Bard.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The examinations took place on Monday 4 and Friday 8 January 1815, before an audience of high state officials and relatives and friends of the lycéens. The seventy-one-year-old Derzhavin, the greatest poet of the preceding age, was invited to the second examination.