По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

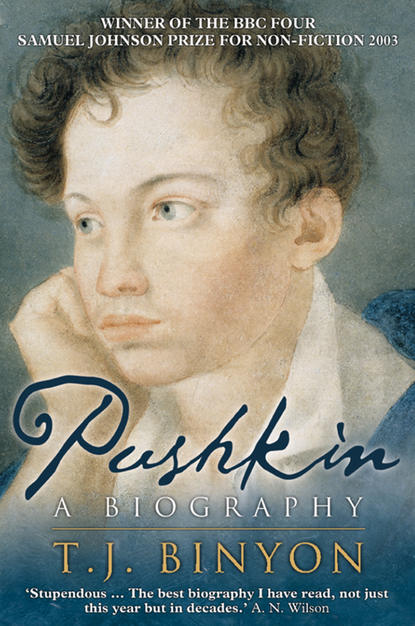

Pushkin

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When we learnt that Derzhavin would be coming â Pushkin wrote â we all were excited. Delvig went out to the stairs to wait for him and to kiss his hand, the hand that had written âThe Waterfallâ. Derzhavin arrived. He came into the vestibule and Delvig heard him asking the porter: âWhere, fellow, is the privy here?â. This prosaic inquiry disenchanted Delvig, who changed his intention and returned to the hall. Delvig told me of this with surprising simplicity and gaiety. Derzhavin was very old. He was wearing a uniform coat and velveteen boots. Our examination greatly fatigued him. He sat, resting his head on his hand. His expression was senseless; his eyes were dull; his lip hung; his portrait (in which he is pictured in a nightcap and dressing-gown) is very lifelike. He dozed until the Russian literature examination began. Then he came to life, his eyes sparkled; he was completely transformed. Of course, his verses were being read, his verses were being analysed, his verses were being constantly praised. He listened with extraordinary animation. At last I was called out. I read my âRecollections in Tsarskoe Seloâ, standing two paces away from Derzhavin. I cannot describe the condition of my spirit: when I reached the line where I mention Derzhavinâs name, my adolescent voice broke, and my heart beat with intoxicating rapture â¦

I do not remember how I finished the recitation, do not remember whither I fled. Derzhavin was delighted; he called for me, wanted to embrace me ⦠There was a search for me, but I could not be found.

(#litres_trial_promo)

âRecollections in Tsarskoe Seloâ made, for the first time, Pushkin known as a poet beyond the walls of the Lycée; the promise it gave for the future was immediately recognized. âSoon,â Derzhavin told the young Sergey Aksakov, âa second Derzhavin will appear in the world: he is Pushkin, who in the Lycée has already outshone all writers.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Pushkin sent a copy of the poem to his uncle; Vasily passed it on to Zhukovsky, who was soon reading it, with understandable enthusiasm, to his friends. Prince Petr Vyazemsky, a friend of Pushkinâs family, wrote to the poet Batyushkov: âWhat can you say about Sergey Lvovichâs son? Itâs all a miracle. His âRecollectionsâ have set my and Zhukovskyâs head in a whirl. What power, accuracy of expression, what a firm, masterly brush in description. May God give him health and learning and be of profit to him and sadness to us. The rascal will crush us all! Vasily Lvovich, however, is not giving up, and after his nephewâs verse, which he always reads in tears, never forgets to read his own, not realizing that in verse compared to the other it is now he who is the nephew.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Vasily, unlike his fellow poets, was not totally convinced of Pushkinâs staying-power, remarking to a friend: âMon cher, you know that I love Aleksandr; he is a poet, a poet in his soul; mais je ne sais pas, il est encore trop jeune, trop libre, and, really, I donât know when he will settle down, entre nous soit dit, comme nous autres.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Recognition led to a widening of Pushkinâs poetic acquaintance. Batyushkov had called on him in February; in September Zhukovsky â after Derzhavin, the best-known poet in Russia â wrote to Vyazemsky: âI have made another pleasant acquaintanceship! With our young miracle-worker Pushkin. I called on him for a minute in Tsarskoe Selo. A pleasant, lively creature! He was very glad to see me and firmly pressed my hand to his heart. He is the hope of our literature. I fear only lest he, imagining himself mature, should prevent himself from becoming so. We must unite to assist this future giant, who will outgrow us all, to grow up [â¦] He has written an epistle to me, which he gave into my hands, â splendid! His best work!â

(#litres_trial_promo)

In March 1816 Vasily Lvovich, who was travelling back to Moscow from St Petersburg with Zhukovsky, Vyazemsky and Karamzin, persuaded them to stop off at the Lycée; they stayed for about half an hour: Pushkin spoke to his uncle and Vyazemsky, whom he had known as a child in Moscow, but did not meet Karamzin. Two days later he sent Vyazemsky a witty letter, complaining of his isolated life at the Lycée: âseclusion is, in fact, a very stupid affair, despite all those philosophers and poets, who pretend that they live in the country and are in love with silence and tranquillityâ, and breaking into verse to envy Vyazemskyâs life in Moscow:

Blessed is he, who noisy Moscow

Does not leave for a country hut â¦

And who not in dream, but in reality

Can caress his mistress! â¦

Only a year of schooling remains, âBut a whole year of pluses and minuses, laws, taxes, the sublime and the beautiful! ⦠a whole year of dozing before the masterâs desk ⦠what horror.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

In April he received a letter from Vasily Lvovich, telling him that Karamzin would be spending the summer in Tsarskoe Selo: âLove him, honour and obey. The advice of such a man will be to your good and may be of use to our literature. We expect much from you.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Nikolay Karamzin, who at this time had just turned fifty, was Russiaâs most influential eighteenth-century writer, and the acknowledged leader of the modernist school in literature. Though best-known as author of the extraordinarily popular sentimental tale Poor Liza (1792), his real achievement was to have turned the heavy and cumbersome prose of his predecessors into a flexible, supple instrument, capable of any mode of discourse. He arrived in Tsarskoe Selo on 24 May with his wife and three small children, and settled in one of Cameronâs little Chinese houses in the park to complete work on his monumental eight-volume History of the Russian State. He remained there throughout the summer, returning to St Petersburg on 20 September. During this time Pushkin visited him frequently, often in the company of another lycéen, Sergey Lomonosov. The acquaintance ripened rapidly: on 2 June Karamzin informs Vyazemsky that he is being visited by âthe poet Pushkin, the historian Lomonosovâ, who âare amusing in their pleasant artlessness. Pushkin is witty.â

(#litres_trial_promo) And when Prince Yury Neledinsky-Meletsky, an ageing privy councillor and minor poet, turned to Karamzin for help because he found himself unable to compose the verses he had promised for the wedding of the Grand Duchess Anna with Prince William of Orange, Karamzin recommended Pushkin for the task. Pushkin produced the required lines in an hour or two, and they were sung at the wedding supper in Pavlovsk on 6 June. The dowager empress sent him a gold watch and chain.

Pushkinâs work â like that of Voltaire, much admired, and much imitated by him at this time â is inclined to licentiousness, but any coarseness is always â even in the Lycée verse â moderated by wit. Once Pushchin, watching from the library window as the congregation dispersed after evening service in the church opposite, noticed two women â one young and pretty, the other older â who were quarrelling with one another. He pointed them out to Pushkin, wondering what the subject of the dispute could be. The next day Pushkin brought him sixteen lines of verse which gave the answer: Antipevna, the elder, is angrily taking Marfushka to task for allowing Vanyusha to take liberties with her, a married woman. âHeâs still a child,â Marfushka replies; âWhat about old Trofim, who is with you day and night? Youâre as sinful as I am,â

In anotherâs cunt you see a straw,

But donât notice the beam in your own.

(#litres_trial_promo)

âPushkin was so attracted to women,â wrote a fellow lycéen, âthat, even at the age of fifteen or sixteen, merely touching the hand of the person he was dancing with, at the Lycée balls, caused his eye to blaze, and he snorted and puffed, like an ardent stallion in a young herd.â

(#litres_trial_promo) The first known Lycée poem is âTo Natalyaâ, written in 1813, and dedicated to a young actress in the serf theatre of Count V.V. Tolstoy. He imagines himself an actor, playing opposite her: Philemon making love to Anyuta in Ablesimovâs opera, The Miller, Sorcerer, Cheat and Matchmaker, or Dr Bartolo endeavouring to seduce Rosina in The Barber of Seville. Two summers later he made her the subject of another poem. You are a terrible actress, he writes; were another to perform as badly as you do, she would be hissed off the stage, but we applaud wildly, because you are so beautiful.

Blessed is he, who can forget his role

On the stage with this sweet actress,

Can press her hand, hoping to be

Still more blessed behind the scenes!

(#litres_trial_promo)

When Elena Cantacuzen, the married sister of his fellow-lycéen Prince Gorchakov, visited the Lycée in 1814, he composed âTo a Beauty Who Took Snuffâ:

Ah! If, turned into powder,

And in a snuff-box, in confinement,

I could be pinched between your tender fingers

Then with heartfelt delight

Iâd strew myself on the bosom beneath the silk kerchief

And even ⦠perhaps ⦠But no! An empty dream.

In no way can this be.

Envious, malicious fate!

Ah, why am I not snuff!

(#litres_trial_promo)

There is far more of Pushkin in the witty, humorous light verse of this kind, when he can allow himself the expression of carnal desire, than in his love poems of the Lycée years â such as those dedicated to Ekaterina Bakunina, the sister of a fellow-lycéen. She was four years older than he and obviously attractive, for both Pushchin and the young Malinovsky were his rivals. In a fragment of a Lycée diary he wrote, on Monday 29 November 1815:

I was happy! ⦠No, yesterday I was not happy: in the morning I was tortured by the ordeal of waiting, standing under the window with indescribable emotion, I looked at the snowy path â she was not to be seen! â finally I lost hope, then suddenly and unexpectedly I met her on the stairs, a delicious moment! [â¦] How charming she was! How becoming was the black dress to the charming Bakunina! But I have not seen her for eighteen hours â ah! what a situation, what torture â But I was happy for five minutes.

(#litres_trial_promo)

There is, however, no trace of this artless sincerity in any of the twenty-three poems he devoted to his love between the summer of 1815 and that of 1817, which are, almost without exception, expressions of blighted love. No doubt Pushkinâs grief was real; no doubt he experienced all the torments of adolescent love. But the agony is couched in such conventional terms, is often so exaggerated, that the emotion comes to seem as artificial as the means of its expression. The cycle begins with the sadness he experiences at her absence; she returns, only for him to discover he has a successful rival; having lost her love, he can only wish for death. âThe early flower of hope has faded:/Lifeâs flower will wither from the torments!â he laments

(#litres_trial_promo) â an image with which, in Eugene Onegin, he would mock Lenskyâs adolescent despair: âHe sang of lifeâs wilted flower/At not quite eighteen years of ageâ (II, x).

Far less ethereal were his feelings for Natasha, Princess Varvara Volkonskayaâs pretty maid, well-known to the lycéens and much admired by them. One dark evening in 1816, Pushkin, running along one of the palace corridors, came upon someone he thought to be Natasha, and began to âpester her with rash words and even, so the malicious say, with indiscreet caressesâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) Unfortunately the woman was not Natasha, but her mistress, who recognized Pushkin and through her brother complained to the emperor. The following day Alexander came to see Engelhardt about the affair. âYour pupils not only climb over the fence to steal my ripe apples, and beat gardener Lyaminâs watchmen,â he complained, âbut now will not let my wifeâs ladies-in-waiting pass in the corridor.â Engelhardt assured him that Pushkin was in despair, and had asked the director for permission to write to the princess, âasking her magnanimously to forgive him for this unintended insultâ. âLet him write â and there will be an end of it. I will be Pushkinâs advocate; but tell him that it is for the last time,â said Alexander, adding in a whisper, âBetween ourselves, the old woman is probably enchanted at the young manâs mistake.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Pushkin made up for the letter of apology with a malicious French epigram:

One could easily, miss,