По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

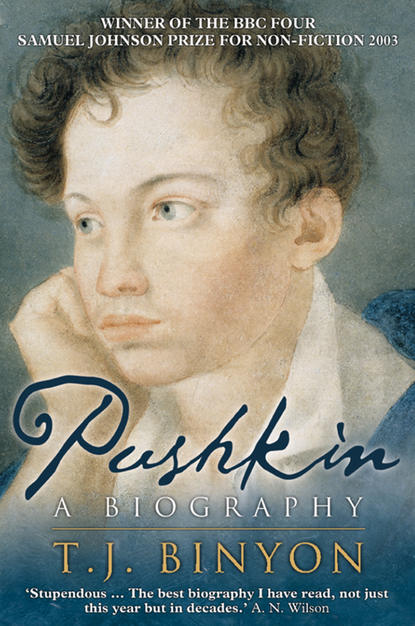

Pushkin

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Full of malice, full of vengeance,

Without wit, without feeling, without honour,

Who is he? Loyal without flattery,

The penny soldier of a whore.

(#ulink_1083e814-a08b-5ce7-a507-6882c35acde6)

(#litres_trial_promo)

Opinions differed on how the abolition of serfdom was to be brought about. In the view of the more conservative, it had to be preceded by constitutional reform. More radical opponents of the institution believed that constitutional reform would merely strengthen the hand of the landowners and worsen the condition of the serfs. Paradoxically, therefore, they saw the solution to lie in the exercise of autocratic power, through an arbitrary fiat of the emperor. It is this view which Pushkin, echoing the ideas of Nikolay Turgenev, expresses in the concluding stanza of âThe Countryâ:

Will I see, o friends! a people unoppressed

And Servitude banished by the will of the tsar,

And over the fatherland will there finally arise

The sublime Dawn of enlightened Freedom?

Towards the end of 1819 Alexander expressed the wish to see some of Pushkinâs work. The request was made to General Illarion Vasilchikov, commander of the Independent Guards Brigade, who handed it on to his aide-de-camp, Petr Chaadaev, possibly knowing that he and Pushkin were acquainted. Pushkin gave Chaadaev âThe Countryâ; it was presented to Alexander, who, reading it with interest, is reported to have said to Vasilchikov: âThank Pushkin for the noble sentiments which his verse inspires.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

He would have been less gracious had he seen Pushkinâs more overtly political verse, much of which was directed at him: such as the playful satire âFairy Talesâ, in which the tsar promises to dismiss the director of police, put the censorship secretary in the madhouse, and âgive to the people the rights of the peopleâ â all of which promises are, of course, fairy tales.

(#litres_trial_promo) The scatological is also pressed into the service of lese-majesty: in âYou and Iâ Pushkin draws a series of comparisons between himself and the tsar, ending:

Your plump posterior you

Cleanse with calico;

I do not pamper

My sinful hole in this childish manner,

But with one of Khvostovâs harsh odes,

Wipe it though I wince.

(#ulink_ecc99c12-7806-5186-a050-61d8ac30d3ad)

(#litres_trial_promo)

Equally unacceptable are the witty, occasionally obscene, epigrams dedicated to prominent members of the government: Arakcheev, Golitsyn, and others such as Aleksandr Sturdza, a high official in the Ministry of Education, known for his extreme obscurantist views.

Slave of a crowned soldier,

You deserve the fame of Herostratus

Or the death of Kotzebue the Hun,

(#ulink_9010132d-d308-5e2c-9eae-3394b2e89970)

And, incidentally, fuck you.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Nikolay Turgenev took Pushkin to task on several occasions, scolding him for âhis epigrams and other verses against the governmentâ and appealing to his conscience, saying it was âwrong to take a salary for doing nothing and to abuse the giver of itâ.

(#litres_trial_promo)

If late eighteenth-century opponents of serfdom had attacked it chiefly as a morally repugnant system, by now it was also seen as a brake on economic progress. But it was not wholly responsible for the post-war crisis which Russia experienced after 1815. In 1825 the Decembrist Kakhovsky wrote to Nicholas I from his cell in the Peter-Paul fortress: âWe need not be afraid of foreign enemies, but we have domestic enemies which harass the country: the absence of laws, of justice, the decline of commerce, heavy taxation and widespread poverty.â

(#litres_trial_promo) This sense among the younger generation of indignant dissatisfaction with the state of the nation was exacerbated â for those who had fought through Germany and France â by the vivid contrast between Russia and the West. But the absence in Russia of freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly forced those who wished for reform to turn to secret political activity. Freemasonry â often connected, if as often unjustifiably, with secret revolutionary activity and for that reason suppressed by conservative governments â provided a means of association. In Russia the number of lodges grew rapidly after the war, and many of the future Decembrists were, or had been â like Pierre Bezukhov in War and Peace â Masons.

On 9 February 1816 six young officers â Aleksandr Muravev and Nikita Muravev, Prince Sergey Trubetskoy, Ivan Yakushkin, and the brothers Matvey and Sergey Muravev-Apostol, the eldest twenty-six, the youngest twenty-one â met in a room of the officersâ quarters of the Semenovsky Life Guards on Zagorodny Prospect. All had served abroad, and all â with the exception of Yakushkin â were Masons. They agreed to organize a secret political society to be called the Union of Salvation or Society of True and Faithful Sons of the Fatherland: from this beginning came the Decembrist revolt of 1825. According to Aleksandr Muravev, the societyâs primary aims were the emancipation of the serfs, the establishment of equality before the law and of public trial, the abolition of the state monopoly on alcohol, the abolition of military colonies,

(#ulink_2d44cf6c-f7bf-5232-9780-41fc794cf5dc) and the reduction of the term of military service. More members were soon enrolled, including the twenty-three-year-old Pavel Pestel, an officer in the Chevalier Guards. âSpent the morning with Pestel, a wise man in every sense of the word,â Pushkin noted in his diary in April 1821. âWe had a conversation on metaphysics, politics, morality, etc. He is one of the most original minds I know.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Charismatic, erudite, with an iron will and a clear vision, Pestel became the moving spirit in the conspiracy. Under his influence a constitution was drawn up, entitled the Green Book, at the same time the Union of Salvation was dissolved and its members joined the new Union of Welfare. And in 1818 Pestel set up a southern branch of the society at Tulchin in the Ukraine.

Much ink has been spilt in debating the question of the extent of Pushkinâs knowledge of the conspiracy, and of his involvement in it. The simplest answer seems the most correct. A number of the future Decembrists were his close friends, and he was acquainted with many others. He frequented houses in which they held meetings; he shared many of the political views of their programme. Nevertheless, he was never, as far as we know, involved in the conspiracy, never invited to become a member of it, never â consciously â present at a gathering of the conspirators, and, though he had a vague suspicion that something was afoot, never knew what this was.

The clearest evidence of his lack of involvement comes from his closest friend at the Lycée, Pushchin. In the summer of 1817 the latter, then an ensign in the Life Guards Horse Artillery, was recruited into the Union of Salvation. âMy first thought,â he writes, âwas to confide in Pushkin: we always thought alike about the res publica.â But Pushkin was then in Mikhailovskoe. âLater, when I thought of carrying out this idea, I could not bring myself to entrust a secret to him, which was not mine alone, where the slightest carelessness could be fatal to the whole affair. The liveliness of his ardent character, his association with untrustworthy persons, frightened me [â¦] Then, involuntarily, a question occurred to me: why, besides myself, had none of the older members who knew him well considered him? They must have been held back by that which frightened me: his mode of thought was well known, but he was not fully trusted.â

(#ulink_575ea66f-82fa-50a2-81ce-fd17180da25b)

(#litres_trial_promo)

Pushkin was still ignorant of the societyâs existence in November 1820, when a guest on Ekaterina Davydovaâs estate at Kamenka, in the Ukraine. A number of the conspirators were present: Yakushkin, Major-General Mikhail Orlov, his aide-de-camp, Konstantin Okhotnikov, and Vasily Davydov, Ekaterinaâs son. Among the other guests were Vasilyâs elder brother Aleksandr and General Raevsky, half-brother to the Davydovs and soon to become Orlovâs father-in-law. According to Yakushkin, the behaviour of the conspirators aroused Raevskyâs suspicions; becoming aware of this, they resolved to dissipate them by means of a hoax. During the customary discussion after dinner, the arguments for and against the establishment of such a society were rehearsed. Orlov put both sides of the case, Pushkin âheatedly demonstrated all the advantages that a Secret society could bring Russiaâ. When Raevsky too seemed in favour, Yakushkin said to him: âItâs easy for me to prove that you are joking; Iâll put a question to you: if a Secret society now already existed, you certainly wouldnât join it, would you?â

âOn the contrary, I certainly would join it,â he replied. âThen give me your hand,â I said. He stretched out his hand to me, and I burst out laughing, saying to him: âOf course, all this was only a joke.â Everyone else laughed, except for A.L. Davydov, the majestic cuckold,

(#ulink_9a13b779-c377-5590-aa04-03fec23e41b8) who was asleep, and Pushkin, who was very agitated; before this he had convinced himself that a Secret society already existed, or would immediately begin to exist, and he would be a member; but when he realized that the result was only a joke, he got up, flushed, and said with tears in his eyes: âI have never been so unhappy as now; I already saw my life ennobled and a sublime goal before me, and all this was only a malicious joke.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Considered objectively, it is difficult to imagine that any serious conspirator belonging to a secret society which had the aim of overthrowing an absolute monarchy would wish to enlist a crackbrained, giddy, intemperate and dissolute young rake, whose heart and sentiments â as his poetry demonstrated â might have been in the right place, but whose reason all too often seemed absent. How could any conspiracy remain secret which had as one of its members someone who, in a theatre swarming with police spies, paid and amateur, was capable of parading round the stalls carrying a portrait of the French saddler, Louvel, who assassinated Charles, duc de Berry, in 1820, inscribed with the words âA Lesson to Tsarsâ?

(#litres_trial_promo) Or who, again in the theatre, could shout out âNow is the safest time â the ice is coming down the Nevaâ?

(#litres_trial_promo) â meaning that, since the pontoon bridges across the river, removed when it froze, could not yet be re-established, a revolt would not have to contend with the troops of the fortress.

In Rome he would have been Brutus, in Athens Pericles,

But here he is â a hussar officer,