По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

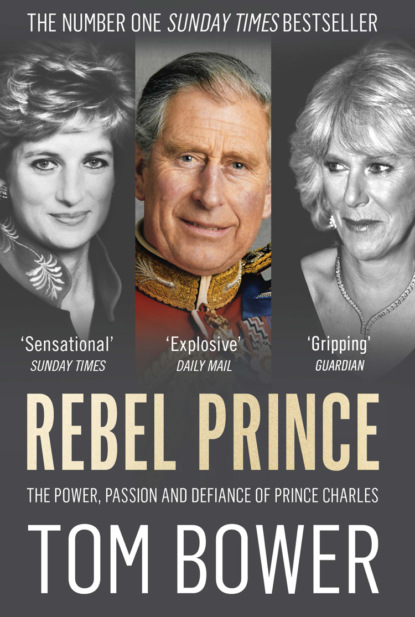

Rebel Prince: The Power, Passion and Defiance of Prince Charles – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

On the instructions of Charles and Camilla, Bolland’s new task was to persuade the queen and her advisers that the heir to the throne’s continuing relationship with Camilla was non-negotiable, and that Charles’s primacy among his siblings should be conspicuously revived. ‘I won’t be trodden down any more,’ Charles declared.

Soon after, Diana called Bolland. Despite his position in the enemy camp, she was easily charmed by him, and he responded in kind to her wiles. Working together, both agreed, was so much easier than fighting. The Camilla campaign, Diana said, was disturbing: ‘I know that as part of the plan she’ll give an interview next week, but if and when she does, I will have to make a statement.’

‘There’s no plan for an interview,’ replied Bolland, aware that Diana’s ability to manipulate the media was legendary.

Her suspicion about the Camilla campaign was shared in Buckingham Palace. For the first five months of Bolland’s job, Robert Fellowes and Charles Anson, the queen’s press secretary, regarded him as benign. While both distrusted the media, they assumed that, given his previous employment at the Press Complaints Commission, Bolland would continue to guard William and Harry’s privacy. Their own priority was to protect the monarchy, not least from Charles heaping greater disrepute upon his own family and endangering his succession. But once both realised that the new man did not share their view of Camilla, Fellowes spoke about destabilising Bolland’s campaign by hiring a private detective to find evidence that he was gay. The plan was ill-conceived. ‘You can just ask him,’ Fiona Shackleton told Fellowes, ‘and he’ll admit it.’

The report to Charles about that conversation inflamed his bitterness towards Buckingham Palace’s officials, particularly Fellowes. His ex-brother-in-law, he knew, wanted to end his relationship with Camilla. In retaliation, Charles ordered Bolland to tell Fellowes and Janvrin that the queen ‘needed to move with the times’. Unsurprisingly, he was ignored. Of the besieged lovers, Fellowes judged: ‘Those two are the most selfish people I have ever met.’

At the end of 1996, a BBC TV programme about the royals and their companions called The Nation Decides echoed this view. In a poll of three thousand people, Charles was voted the most hated royal, just above Camilla. The popular dislike was personal. A further telephone poll in January 1997 found that 66 per cent of Britons supported the monarchy, slightly less than in previous years.

Finding a permanent solution to the conundrum of Charles, Diana and Camilla was the elephant in the room at the 9 a.m. daily meetings in Buckingham Palace, where the private secretaries and other advisers to the royal family met over coffee to discuss events and problems. Once mundane matters had been agreed, the officials forlornly considered the War of the Waleses. Charles, Fellowes suspected, was unwilling to surrender or even compromise. His judgement was right: Charles fought to win, regardless of any collateral damage. Like Fellowes, the influence of the other officials at the meeting was limited. All deferred to the queen. She could have summoned Charles and Diana to order both to cease manipulating the media, or asked Robin Janvrin, trusted by Diana as an honest broker, to mediate a ceasefire. Or she could have issued an ultimatum to Charles to choose between the crown and Camilla. Instead, she ignored the problem.

The queen’s fence-sitting reflected her doubts about Charles’s judgement, and also the erosion of her own self-confidence. Five years earlier, her ‘annus horribilis’ speech, written by Robert Fellowes, had revealed how vulnerable she was. Suffering from the divorce of three of her four children and having witnessed Windsor Castle engulfed in flames, she told Britons, ‘No institution – city, monarchy whatever – should expect to be free from the scrutiny of those who give it their loyalty.’ Her honesty had won widespread affection. Nevertheless, as 1997 began, she still felt battered.

‘I cannot believe what’s happened to me,’ she confessed to an adviser after describing the state of her family and her continuing struggle with Charles.

‘It’s common today,’ was the consoling reply.

Philip, her most loyal friend, offered little comfort. He merely encouraged distrust of Charles without making any meaningful suggestions other than to reinforce the queen’s anger towards Camilla.

On Charles’s behalf, Stephen Lamport was in no position to offer a solution. A cautious man seconded from the Foreign Office, he was regarded as indecisive. Cast as middle-class, Lamport knew that his income, home and perks would be terminated at a moment’s notice if the prince were displeased. ‘Stephen,’ a courtier explained to a newly appointed official, ‘hasn’t got much money, so his job is important for him.’ Every obedient courtier, irretrievably bound by Charles’s temperament and outbursts, would search his employer’s face for signs of that hour’s attitude. Charles’s rages or frosty blanking could be calculated to assert his supremacy over every official, or just reflect that moment’s volatility. Lamport was employed to obey if his advice was rejected, not to take responsibility. Loyal to the monarchy, he agreed to be led by his new deputy; after all, Bolland was acting on Charles’s behalf with Camilla’s approval. Whenever Patrick Jephson complained that Bolland was ‘monstering the media’, Lamport would reply: ‘I can find no evidence.’ His sharpest reproach to Bolland was ‘We don’t do that sort of thing.’ Both men understood their terms of employment – with Charles, only unquestioning obedience was acceptable.

3

The Masters of Spin (#ulink_34a2d3f4-36ec-51ff-8ab2-7a2c2f366f56)

On 1 May 1997, ‘spin’ won New Labour’s landslide victory. Charles, like every powerbroker, was in awe of the conjurer of those arts, Tony Blair.

The two men had first met at a dinner in 1995 at St James’s Palace. Blair was hardly a passionate royalist. Only the previous year, he had advocated a smaller, Scandinavian-type monarchy, curbing the rights of the royal family to engage in public controversy. The queen, he suggested, needed to decide whether the monarchy should ‘retreat into isolation and the old hierarchical order, or seek to become more like a normal family’. His ideas, popular in the Labour Party, had been criticised by Charles for seeking to transform the family into something ‘more pompous and harder to approach’.

Despite their differences, Charles and Blair soon arranged further meetings. Familiarity had not lessened the prince’s cynicism about those in government. Concerned for his two passions, the environment and education, he believed politicians to be dishonest, especially about young people’s supposed inability to read and enjoy Shakespeare. ‘I don’t see why politicians and others should think they have the monopoly of wisdom,’ he said. Unintentionally, he aspired to emulate the status which Samuel Johnson had attributed in 1783 to his unconventional predecessor, the future George IV: ‘the situation of the Prince of Wales was the happiest of any person’s in the kingdom, even beyond that of the Sovereign … the enjoyment of hope – the high superiority of rank without the anxious cares of government, – and a great degree of power, both from natural influence wisely used, and from the sanguine expectations of those who look forward to the chance of future favour’.

Charles had travelled a long way since his first serious encounter with senior functionaries, in 1970. ‘I pointed out,’ he wrote after an extended meeting with President Nixon in Washington that year, ‘that one must not become controversial too often, otherwise people don’t take you seriously.’ But he added, ‘To be just a presence would be fatal.’ He refined that thought after flying with Ted Heath and three former prime ministers to the funeral of Charles de Gaulle later the same year. ‘Perhaps the most important lesson,’ Dimbleby concluded from his conversations with Charles, ‘was that his future would be frustratingly circumscribed unless he chose to make more of his role than precedent strictly required – or observers expected.’ Twenty-three years later, Charles told an aide, ‘I have always wanted to roll back some of the more ludicrous frontiers of the Sixties in terms of education, architecture, art, music and literature, not to mention agriculture.’ In middle age, he felt underused and under-appreciated by successive governments. Instead of ceremonial duties, he wanted to promote British culture and industry.

Tony Blair had no interest in Charles’s ambitions. Outside the prince’s hearing, he did not conceal his feelings about the royal family. At best, he gave the impression to his senior staff that he would ‘wing it’ with the royals, while officials at St James’s Palace concluded that Blair preferred to keep away from those he did not know or particularly like. Nevertheless, he played the part, and was not immune to being impressed. After his first royal audience, he recounted with awe how the queen was ‘clued up on current affairs’.

On his first visit to Balmoral, Blair wore a tweed suit and instructed Cherie, although anti-royalist, to be on her best behaviour. He judged the heir to the throne to be a mix of traditional and radical: both princely and insecure, nervous about the public’s reaction towards him and uneasy about informality. He had been spared Charles’s pained response to his letter which started ‘Dear Prince Charles’ and was signed ‘Yours ever, Tony.’ Lamport called Downing Street to stipulate that in future Charles wanted Blair’s letters to start ‘Sir’ and to end ‘Your obedient servant’. The prime minister’s private secretary replied that he refused to ask his master to change his style. Blair’s ignorance of the required etiquette extended to an invitation from Downing Street for Diana and her sons to spend a day at Chequers. Charles was not informed, which he complained was a breach of protocol.

When on 1 July 1997 Charles met Blair in Hong Kong for the former British colony’s handover to China, he put such lapses to one side. Instead, in a journal he wrote soon after, he praised Blair as ‘a most enjoyable person to talk to – perhaps partly due to his being younger than me!’ The prince found it ‘astounding’ that the prime minister listened to him, but he was critical of Blair’s ‘introspection, cynicism and criticism [which] seem to be the order of the day. Clearly he recognised the need to find ways of overcoming the apathy and loss of self-belief, to find a fresh national direction.’ As a traditionalist, Charles also disliked New Labour’s use of focus groups and reliance on untested advisers: ‘They take decisions based on market research or focus groups, or papers produced by political advisers or civil servants, none of whom will ever have experienced what it is they are taking decisions about.’ Charles did not consider that the same could be said about him.

He had arrived in Hong Kong in a bad mood, having been forced to fly Club Class in the chartered British Airways plane because government ministers had grabbed all the first-class seats. ‘It took me some time to realise,’ he wrote in his journal, ‘that this was not first class (!) although it puzzled me as to why the seat seemed so uncomfortable. Such is the end of Empire, I sighed to myself.’ He added a lament about his family’s last use of the royal yacht Britannia before it was scrapped. Without those perks and privileges, he feared, his status was diminished.

Blighted by monsoon rain, the ceremony in Hong Kong was dire. In his private journal, headed ‘The Handover of Hong Kong or The Great Chinese Takeaway’, Charles was scathing about the Chinese leaders, in his view ‘appalling old waxworks’. Sympathetic to the Tibetans, he regarded Beijing’s rulers as ‘corrupt’, and ridiculed the People’s Liberation Army for an ‘awful Soviet-style display’ of goose-stepping. Wind generators, he noticed, were employed to enable the Chinese flags to ‘flutter enticingly’. Charles appeared unaware that his host, President Jiang Zemin, was the architect of the phenomenal economic growth that had tripled China’s average wages in fifteen years and was transforming the country into a global power.

Blair would have sympathised with Charles’s mockery. His own meetings with the Communist Party chiefs were disappointing. By contrast with the prime minister’s tactful concealment of his true feelings, his pugnacious spokesman Alastair Campbell was uncharacteristically generous towards Charles during the visit, summing him up as ‘a fairly decent bloke, surrounded by a lot of nonsense and people best described as from another age’. Campbell astutely added that there was ‘something sad about him. All his life, even on the big issues, he had to make small talk, surrounded by luxury, as here, people fawning on him, and yet somehow obviously unfulfilled,’ and with his ‘private life a mess’.

Campbell was unaware of the full scope of Charles’s arrangements during the visit. The prince never travelled without Michael Fawcett. Dressed as a perfect gentleman in an Anderson & Sheppard suit with a silk handkerchief in the breast pocket, a Turnbull & Asser shirt and a silk tie, Fawcett flattered his employer by adopting his style and mannerisms, fashioning himself as Charles’s doppelganger, even furnishing his home with items purchased from the prince’s suppliers.

With a love of grandeur and extravagance similar to his master’s, he was skilled at satisfying Charles’s expectations, and set himself to provide the luxury Charles demanded day and night. Every morning, wherever he travelled, the prince was woken by Fawcett who ran his bath and laid out his clothes – matching suit with shirt, socks, tie, handkerchief and highly-polished shoes – all carefully folded between tissue paper for the journey. Every night Fawcett prepared Charles’s bedroom with masterly attention to detail. With familiarity spawned by living close to his employer since 1981, he could anticipate his employer’s requests without any order being issued. He would discreetly replenish the royal lavatory paper, clean up vomit, wash the royal boxer shorts by hand (salacious gossips on the Sun credited Fawcett with revealing that Charles’s underwear had to be specially adapted because he was so well endowed), guarded his liaisons, bowed to his tantrums, tested the royal boiled eggs and always spoke in deferential tones. At each of Charles’s homes he supervised every detail, ensuring that the gravel on the drive was raked, the paintings hanging precisely, the cushions properly positioned, the kitchens supplied with organic food from the prince’s favourite suppliers, the elaborate flower arrangements refreshed daily, and the dining table covered with the appropriate linen tablecloth, silver cutlery and candlesticks.

Some of those who witnessed Fawcett’s outbursts of fury when he spotted an error considered him a thug, but Charles embraced this one servant who, in his eyes, could do no wrong. Most royals have a weakness for a special retainer. The queen’s was Angela Kelly, her personal assistant; Queen Victoria’s her beloved attendant John Brown. Charles would confess, ‘I can manage without just about anyone except Michael.’ Operating like a general, Fawcett was given the keys to the front and back doors of Charles’s homes – and control over his life.

Shortly before leaving for Hong Kong, Fawcett was told about an important dinner party that would be hosted by his master during the trip. Charles was focusing on his charities, for which he hoped to raise money from American billionaires. ‘Show your good side,’ said Mark Bolland. Searching for a new fundraiser, the prince asked Geoffrey Kent for a recommendation. Kent had heard about Robert Higdon from Alecko Papamarkou, a Greek banker. At the time Higdon was accompanying Margaret Thatcher on her speaking engagements, having been recruited by Thatcher’s son Mark, who knew of the American’s successful work for Ronald and Nancy Reagan.

In July 1995, Colin Amory, an architect and sometime adviser to Charles, invited Higdon to meet him and Geoffrey Kent at Claridge’s. Higdon arrived with the billionaire American publisher Kip Forbes, who was said to have first met him in a Red Lobster restaurant in Florida. Over a drink, Amory and Kent told Higdon that the Prince of Wales’s Foundation in America, which had been created two years earlier, needed a professional fundraiser.

‘I have met Charles,’ said Higdon, ‘when he and Diana came to the White House to meet the Reagans.’

Soon after, Kent asked Higdon as a trial to arrange a dinner with potential donors.

‘What’s your platform?’ asked Higdon.

‘The Prince of Wales’s interest in architecture,’ replied Kent.

‘No one’s interested in that over here,’ said the American bluntly. ‘I raised money for the Frick, but for the prince there’s nothing to discuss.’

Kent managed to overcome Higdon’s objections, and a dinner party was arranged in New York for people who had previously ‘written a cheque for Charles’. To Higdon’s surprise, 150 people accepted the invitation, including members of the Rockefeller family, and the event was reported in the city newspapers’ society columns. ‘I raised about £75,000,’ said Higdon. ‘I was the money whore.’

Delighted by the evening’s success, Charles asked Kent to sign up the American for further fundraising. ‘I’d need to meet Charles again,’ replied Higdon. Before long he was in the prince’s office at St James’s Palace. ‘We chatted as long-lost friends,’ said Higdon. With Lamport sitting in, ‘I bluntly told Charles what would and wouldn’t work.’

Lamport interrupted: ‘You cannot speak to His Royal Highness like that.’

‘Lamport didn’t like me or want me to help,’ Higdon concluded, ‘but Charles trusted me.’

In January 1997 Charles formally asked Higdon to run his foundation under Kent’s chairmanship. Within weeks the new recruit encountered obstruction: ‘The gatekeepers wouldn’t let me speak to Charles. Fawcett and others were fighting against me. I saw no good.’ Eventually he met Charles for a third time, at Birkhall, the queen mother’s house on the Balmoral estate. ‘You won’t get a dime for your architecture,’ he told Charles, ‘because you’ve got a bunch of cuckoos in this building wanting a pay cheque.’ He blamed Fawcett for taking too much interest in his fundraising, and continued, ‘You can be so much more and do much more if you have a global vision.’ Charles agreed to his reorganising the foundation.

Shortly after, Lamport telephoned Higdon to tell him, ‘We need a fundraising dinner for HRH during the handover in Hong Kong.’ The target, he said, was $1 million. Higdon now understood that every foreign trip organised by the British government for Charles would be, whatever else was intended, an attempt to raise money for his charities – ‘So I became Mr Cash Cow.’ Against the odds, he managed to corral a group of local plutocrats.

To set the table for the dinner, Fawcett had brought a full set of eighteenth-century china and glasses to Hong Kong, which would replace the governor’s nineteenth-century equivalents. He had also brought a set of special bells used by Charles to summon his staff. After arranging the table decorations, Fawcett turned to the seating plan. The potentially largest donors would be closest to the prince. To ensure that everything went smoothly during the dinner, Fawcett stood behind Charles, protecting him from careless hands spilling wine or food, and waiting, as ever, for the royal click of the finger should his boss need something – the china cup filled with his special tea, an orchestra at short notice, or even, thinking ahead to another event, a private plane. Based on such knowledge and trust, Fawcett was Charles’s Rasputin, empowered to outflank everyone. For that reason, the queen had no time for him. At a dinner in Holyrood, she cringed when his name was mentioned. Fawcett appeared unenthusiastic about Higdon’s role. Any competitor for Charles’s attention aroused his antagonism, even those who were helpful. ‘I was the new enemy,’ Higdon recalled after he had successfully met his $1 million target.

One group that Fawcett ignored was politicians, and among the Blairite luminaries to whom Charles was naturally attracted was Peter Mandelson, a principal architect of New Labour’s electoral success. Known as ‘the Prince of Darkness’, Mandelson sought an introduction to Charles with the help of Carla Powell, the wife of Margaret Thatcher’s foreign affairs adviser Charles Powell. Powell had invited Camilla to a dinner at which Mandelson made a pitch for a relationship with Charles.

Camilla’s favourable report back sealed the ambition of Labour’s spin maestro. He was invited to lunch at Highgrove the month after the Hong Kong trip. Charles’s ostensible reason was to urge him to discourage Labour’s proposed ban on fox-hunting. Pleased that their guest seemed sympathetic, Camilla treated Mandelson as an ally. Recalling election night, she told him that she had worn a red dress at dinner with friends, telling them, ‘I’m dressing for the future.’ Now the conversation drifted to the problems caused to the government by the recent messy divorce of the foreign secretary Robin Cook. After listening to Mandelson’s uncharitable judgement of his beleaguered opponent, Charles mentioned his prime concern. What, he asked, did ministers think about him, the Prince of Wales? In a reassuring manner, Mandelson replied that they saw him as hardworking and civilised, with a deep social conscience. He then grasped the nettle: ‘Some people have gained the impression you feel sorry for yourself, that you’re rather glum and dispirited. This has a dampening effect on how you are regarded.’

Charles reeled. But Mandelson had not finished, and turned to the prince’s relationship with Camilla: ‘You will need to be patient. Let things find their own level and not force the pace.’

Again Charles looked stunned. After Mandelson had left, he beseeched Camilla, ‘Is that true? Is that true?’

‘I don’t think any of us can cope with you asking that question over and over again for the next month,’ she replied.

‘Well, then,’ said Charles, ‘how about for just the next twenty minutes?’

Humour was often the saving grace between them. Camilla was Charles’s rock, and nothing would deter him from hosting a grand party to celebrate her fiftieth birthday in July 1997. The news aroused Diana’s bile and Robert Fellowes’s fury. According to reports from Buckingham Palace, Fellowes intended to ask the queen not to allow the event. That news encouraged Charles to order Fawcett to plan a spectacular celebration. While he would not remarry, the prince told his former brother-in-law, he would not abandon Camilla. On the contrary, he wanted the world to appreciate her as much as he did. He reported back to Camilla that Fellowes had surrendered.

The birthday party was successful, but the obstacles to progress were confirmed by a BBC poll after a TV show, You Decide. Sixty thousand viewers voted that Charles should not be crowned if he married Camilla. Few voted in his favour.

Undeterred, Charles wanted a final reckoning with Diana. In the war of books, he contemplated cooperating with Penny Junor, a well-known journalist sympathetic to his cause and familiar with some of Camilla’s Wiltshire set. Junor’s book would focus on presenting Camilla in a favourable light, but would also disparage Diana and portray Charles as the victim of a sick wife. To protect himself from the kind of recriminations that had followed Jonathan Dimbleby’s book, Charles decided that any cooperation with Junor should be channelled through Bolland.