По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

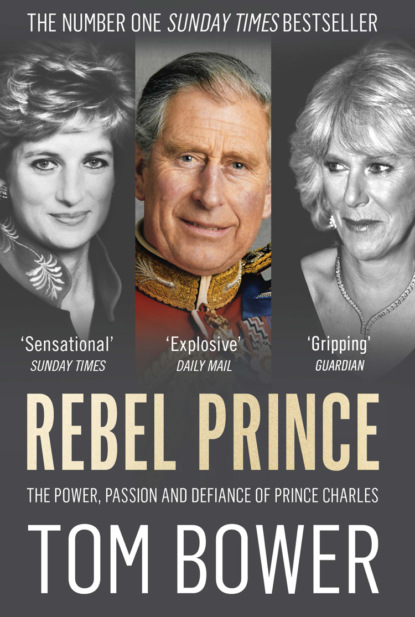

Rebel Prince: The Power, Passion and Defiance of Prince Charles – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Overcoming the obstacles to a constitutional debate depended upon neutralising the queen’s dislike of change. ‘Well, my father told me this …’ she would still regularly say. Wedded to George VI’s influence and with the queen mother urging the most reactionary decisions during her daily telephone calls to her daughter, the queen was shaped by Edwardian precedents. Rigidly conservative, she refused to allow even moving any furniture in Balmoral from the place assigned by Queen Victoria. Charles, she feared, would change everything, not least out of pique. ‘My son,’ she once complained to a nobleman, ‘resents me because I taught him the alphabet.’

On many matters she would defer to her husband, who was well aware of the problems they all faced. ‘Throughout history,’ Philip told an adviser, ‘there’s been a difficult relationship between monarch and heir. It’s not a job but a predicament.’ He wanted his children to follow his way of doing things, but knew that Charles would not forgive his father’s apparent ‘sins’ – including his ordering Charles, as a child, to wear corduroy trousers to a birthday party, the only one present to do so. Even as a middle-aged man, Charles still felt the legacy of that trivial humiliation. He also lacked his mother’s genius for concealing what she truly felt and separating her personal values from those of the nation. He would never be able to emulate her landmark speech at a lunch in Whitehall to celebrate her golden wedding anniversary in November 1997, when she had volunteered that the monarchy’s existence rested on popular approval – adding, to applause, that she herself was willing to change after listening to the public.

Charles disliked those sentiments. He preferred to confront anyone he disliked, regardless of the fallout. Unlike his mother, he failed to provide a sense of solidarity or stability. He did not stand as a symbol of the country and its heritage, or personify an idea. Not astute enough to create illusions when needed, or to float above the rancour, he was content to pose a threat.

Negotiating peace with the unpredictable heir was complicated by the appointment to head the queen’s household of Lord Camoys, a banker from an old Roman Catholic family, as the lord chamberlain. To Charles, Camoys represented the old guard, with its antediluvian understanding of the monarchy. His dislike was exacerbated by Camilla’s complaint that Camoys had once accused the Parker Bowles children of cheating in a school race.

Since the 1980s, Charles had sabotaged every attempt by the queen’s advisers to coordinate their two courts. To him, Buckingham Palace was not a homogeneous organisation. In his opinion, little had changed since he was born. Within the immutable layers of rank, right down to the servants who laboured in the basement of the palace, there was unyielding respect for the queen and fear of her displeasure, but also an understanding that individual power depended on every courtier’s relationship with his or her immediate superior, the high value of intimate information, and ultimately access to the queen. Charles’s disdain for that culture was magnified by his dislike of Fellowes, Janvrin and now Camoys.

Janvrin’s hope that he could fashion a new relationship with St James’s Palace rested on Stephen Lamport’s skill in persuading Charles to resist his instincts and stabilise his relationship with Buckingham Palace. But that depended on Charles’s whims. Giving honest advice to a man who would explode when contradicted was no easy task, especially as the prince once confessed, ‘My problem is that I believe the last person I spoke to.’

Unlike the queen, Charles frowned on people with different ideas from his own. While her lack of dogmatism encouraged free discussion, he was closed to alien thoughts. Every day his public and private life threw up difficulties, and every day Lamport tried to tone down Charles’s opinions, especially about the environment, education and fox-hunting – although after their lunch at Highgrove, Peter Mandelson had told journalists that any private member’s attempt to introduce legislation banning hunting would not be supported by the government.

In their daily meetings, Lamport tried to measure Charles’s intentions in comparison with the precedents established by his predecessors over the previous two hundred years. He then gave advice, but he could not always gauge Charles’s reaction. To reach the ideal decision on almost any matter required him to follow a convoluted and uncomfortable route. If his advice were rejected, Lamport suffered in isolated silence: ‘I blame the vipers’ nest in Charles’s private office,’ observed an official in Buckingham Palace about the tortuous process. There were layers of hierarchy, with everyone attempting to climb the greasy pole. Whatever was said, one never knew how far it might go, ‘who could be trusted and how it would be twisted’. Buckingham Palace and St James’s Palace suffered from identical manipulative tussles.

Uncertain about the best course, in the summer of 1998 Janvrin and Fellowes invited Alastair Campbell for lunch. Charles’s stubborn grudge, they confided, was a tough, long-term problem made worse by their distrust of Bolland. True to his conviction that ‘spin’ was the answer to most difficulties, Campbell urged the two to ‘get a grip’ and embrace a new generation by appointing Simon Lewis, a Blairite public relations expert. On Campbell’s recommendation, Janvrin immediately hired Lewis as Buckingham Palace’s new spokesman. Unlike his predecessors, Lewis was told to bridge the gap between the monarch and the people – or, at least, to break the mould.

Adopting the Blairite tactic of targeted messages, Janvrin believed, would modernise the brand and help define the monarch’s renewed contract to serve the country. Inevitably, some courtiers were puzzled that he was putting so much faith in a New Labour marketing man with no experience of the royal family. Janvrin replied that Lewis and Camoys would repair the monarchy’s vulnerability. As the first anniversary of Diana’s death approached, he feared renewed damage from the tabloids.

Lewis, as a newcomer, struggled to understand the tension between the palaces. Hearing critical comments in Buckingham Palace about Charles’s weaknesses, the contamination caused by Camilla, and how Bolland was promoting the prince at the expense of other members of the family, bore little resemblance to Westminster’s wars. Lewis’s proposals to start lobby briefings, issue statements, send an annual report on the queen’s behalf to twenty million homes, and harness Buckingham Palace to Cool Britannia (New Labour’s gospel to revolutionise Britain) bewildered Janvrin’s critics. He replied that changing the culture was essential to prepare for a modern monarchy.

Charles disagreed. Conjuring an air of change was merely colourful spin, in his opinion, and ignored the House of Windsor’s instinct for self-preservation. Ever since the Saxe-Coburgs had reinvented themselves as the Windsors in 1917 to avoid the fate of the Tsar of Russia, the Kaisers of Germany and Austria and the downfall of other minor European monarchs, the queen had separated herself from Britain’s aristocracy. Unimpressed by titles, the royal family was aware of the country’s hereditary families only if they were genuine friends or were criticised by the media. The natural order, with the monarch at the head of a pyramid supported by the landed nobility, had vanished.

The gentry’s loss of power was of no interest to St James’s Palace. After a decade of gossip and misbehaviour, Charles’s household yearned for a period free of notoriety. His officials’ expectations were frustrated by the prince’s feudal exercise of power, a different kind of misbehaviour.

Some long-term employees who had been granted a home were obliged to receive a visit from Charles as a reminder of their place in the scheme of things; others were invited for dinner, or to a garden party at Highgrove. Lesser mortals received gifts. The prince dispensed presents, graded by his opinion of their importance, to paid and unpaid employees: whisky glasses engraved with his motif, or designer salt and pepper grinders. A typed letter signed by Charles was welcome, but the greatest trophy was a handwritten message in black ink. The universal fear was his expression of displeasure, signalled by the absence of a ‘please’ or ‘thank you’. Finely calibrated blanking – like a Mafia don’s kiss of death – was an overt threat to the courtier’s job, income, school fees and self-respect. After dismissal, there was nothing. Being cut off without even a much-prized Christmas card to acknowledge the relationship was ‘so hurtful’, repeated all the casualties. Charles had made himself clear that they were no longer useful. Loyalty was always a one-way street.

Preferring to live at Highgrove to enjoy his garden and to be near Camilla, Charles summoned people to drive the two hours from London for even the briefest meeting, and would regularly keep them waiting. Yet few refused. The outstanding garden, more than thirty-five years in the making, had been designed by a succession of experts. Molly Salisbury, Rosemary Verey, Miriam Rothschild, Julian and Isabel Bannerman, one after another, were enlisted to fill the landscape with trees, hedges, wildflowers, fountains, rare breeds of farm animals and architectural features, all blended into a romantic safe haven. In return, the heir to the throne offered conditional gratitude. Professional gardeners were divided about the extent of Charles’s own contribution.

Roy Strong was summoned to advise on the cultivation of hedges. He spent days with his own gardener perfecting his ideas. At the end, he submitted his employee’s bill for £1,000 – and was never asked to return, or even thanked. Strong had personally inscribed a copy of his book on gardening to Charles, but it was left in a waiting room rather than included in the prince’s library. ‘He’s shocked by the sight of an invoice,’ Strong noted. ‘So he likes people who don’t charge for their services.’ Inevitably, none of those advisers was individually thanked after Charles received the Victoria Medal of Honour from the Royal Horticultural Society, presented by the queen for his services to gardening, in 2009.

‘Grace and favour’ took on a new meaning. To make up a floragim (a book of paintings of Highgrove’s flowers), Charles recruited over twenty artists to paint two or three flowers each, for free. Similarly, he approached Jonathan Heale, a woodcut artist, for some of his work, which he expected to be donated as a gift. One of the few artists known to have rebuffed similar demands was Lucian Freud. Would Freud swap one of his oils – which sold for millions of pounds – for one of Charles’s watercolours? ‘I don’t want one of your rotten paintings,’ Freud replied.

Strong, despite the rebuffs, narrated a BBC TV documentary about Highgrove. He intended to report that Charles had followed fashion by asking Molly Salisbury to build a ‘potager’ – a vegetable garden, but his draft commentary was returned from Charles’s office with the rebuke, ‘His Royal Highness never follows fashion.’ Strong removed the comment. Charles, clearly, stood ‘above fashion and is always right’. Thereafter, Strong stepped back: ‘I stayed on the edge with Charles. It was less dangerous.’

In the same spirit, in 1998 Charles called Tim Bell, Margaret Thatcher’s media adviser, to ask whether he could borrow Elizabeth Buchanan, employed by Bell to develop relationships with Conservative politicians and bankers, for three days a week. ‘You can’t turn down a royal summons,’ said Bell, knowing that Charles would not pay Buchanan’s salary. Buchanan went to work at the royal home.

Charles had chosen an utterly devoted woman. ‘Elizabeth curtsied lower than anyone thought possible,’ one household member noticed, ‘and then for longer than necessary. She worked all the hours God gave and then some God hadn’t thought about.’ Dubbed ‘the virgin queen’ by her fellow staff, she understood the ritual, the pattern and the access Charles expected. He would sit for hours, and sometimes for a whole day, dressed in eccentric clothes in an armour stone garden surrounded by trees and wildflowers, while Buchanan, ‘blinded by devotion’, pandered to his requirements. On occasions when Charles, in the midst of a meal, took exception to the conversation – especially criticism of his opinions – and stormed out, she was summoned by Michael Fawcett to smooth things over with the guests and to placate the prince. When Charles, near the end of a seemingly pleasant dinner, abruptly headed to his study to spend hours handwriting letters late into the night, it was Buchanan who made excuses to his guests. Tim Bell was unsurprised when she became a full-time employee. Her salary did not reflect her new position as an assistant private secretary, but the media man quietly bridged the gap.

5

Mutiny and Machiavellism (#ulink_99ad3a7c-cc96-59bc-8ad3-3c03a36c2e41)

In mid-1998, Mark Bolland and Fiona Shackleton were lunching at the Ivy restaurant off St Martin’s Lane when both their mobile phones rang. The Highgrove switchboard connected the prince. ‘I’ve got a terrible problem,’ said Charles. ‘I’ve had a delegation of the staff led by Bernie and Tony and they say that everyone will resign unless Michael Fawcett goes.’

The mutiny among Charles’s staff at Highgrove had been brewing for weeks. Fawcett had been imposing unreasonable demands, especially on five of the staff serving under him: a valet, two sub-valets, an equerry’s assistant and a chauffeur. The result was a revolt by a group of people noted for exaggerating the smallest inconveniences out of all proportion. However, on this occasion Fawcett’s behaviour would seem to have been insufferable. Fearful of losing all his employees, Charles had instantly surrendered to the delegation and agreed that Fawcett should resign, despite his seventeen years’ service. Then, immediately regretting his decision, he had telephoned Bolland and Shackleton. Both were joyful at the news. Later that afternoon, on Stephen Lamport’s orders, Bolland drove to Highgrove. ‘Make sure he’s fired,’ were Lamport’s parting words. In unison, the prince’s closest advisers ‘went into overdrive to make sure Fawcett left before Charles changed his mind’. The thirty-five-year-old, they agreed, was a hated bully. Regardless of Fawcett’s usefulness, no one could understand why Charles had chosen to live alongside such a seemingly unpleasant man.

Bolland entered the prince’s study to be ‘greeted by the sight of Charles and Fawcett crying together’. Amid their tears, Charles told Fawcett that he would have to go, but that provision would be made for him to continue working for him privately. An announcement was made that Fawcett’s departure was ‘entirely amicable’. Commentators, misled by spokesmen, mistakenly reported that Fawcett was the casualty of a ‘war’ within St James’s Palace between the old guard and the modernisers.

The backlash began soon after. Led by Patty Palmer-Tomkinson, Charles’s friends urged him to recall Fawcett.

‘Poor Michael,’ said Palmer-Tomkinson.

‘It’s not my fault,’ replied Charles. ‘They made me do it.’

The following Friday, Charles and Camilla were invited to Chatsworth by Debo, the Duchess of Devonshire. Debo, at seventy-eight the youngest of the Mitford sisters, was a favourite of Charles. Amusing and resourceful, she was independent-minded and the most practical of duchesses, having rescued the family estate at Chatsworth with her marketing zeal. During his marriage to Diana, Charles and Camilla had often been welcomed by Debo to stay while they discreetly hunted with the Meynell in Derbyshire. Less discreetly, she revealed to a confidential source that Charles and Camilla slept in the same bed on these visits, and that Charles was submissive to Camilla. ‘That’s why the relationship works,’ she had said, smiling, hinting at a deeper meaning to Charles’s expressions of adoration in the Camillagate tape.

The next day, while Charles and Camilla were out hunting, Debo summoned Bolland and Lamport to drive up immediately from London. Within minutes of their arrival, she reprimanded them: ‘You’re making Charles unhappy about Fawcett. This must stop.’ Charles, it became obvious, had been easily persuaded by his hostess that Fawcett was too important to lose, especially as Camilla remained so indebted to him.

During the months after her separation from her husband, Camilla had lived in comparative impoverishment. Receiving £20,000 a year in alimony, she could barely afford to run her Wiltshire home. Without Fawcett’s help, Debo reminded Bolland and Lamport, Camilla’s life would have been ‘seriously unpleasant’. Thanks to him, food had been sent from Highgrove, her laundry was returned pristine, and Andy Crichton, a former police protection officer, had been made available to act as her driver. Moreover, Fawcett was a great survivor. Ten years earlier, John Riddell had arranged his dismissal, only to discover that Charles had reneged on their agreement. The same would happen now. Fawcett, Debo made clear, was non-negotiable. As one of Charles’s senior staff was to observe, ‘The man who puts the death mask on the king will be Fawcett.’ However, neither man was persuaded to reverse his dismissal.

On their return from hunting, Charles and Camilla were frosty towards the two private secretaries, whom they inexplicably blamed for Fawcett’s plight. One solution, they nevertheless speculated, would be for him to be employed by Robert Kime, the prince’s favourite interior decorator. Kime was invited to Highgrove for dinner the following Saturday.

Around the table a week later sat Charles, Kime, Lamport and Bolland. Kime advised that Fawcett be employed as a private contractor, as Charles had suggested originally, but after listening to Bolland and Lamport discuss the valet’s fate, Charles expressed his fears. For the past week he had lived through the horror of life without Fawcett. No doubt the valet had crossed the line by bullying the staff, but he was more important than any friend. He also posed an enduring threat, as at any time he could succumb to the temptation to sell his story to the media.

Kime was concluding that Fawcett was not going anywhere when there was a commotion. Arriving late, Camilla had entered Highgrove through the kitchen, where several employees were milling about. Dressed as the woman in charge rather than in her usual country clothes, she told them, ‘I hear you’re being beastly to Michael and I’m angry with all of you.’ Her direct language, Roy Strong later said, brought ‘the common touch to the household which Charles lacked’. After extracting grovelling apologies, she headed for the dining room, where Kime was pleading Fawcett’s case. Finally, at 2 a.m., it was agreed that he would stay, and that some of the members of staff who had complained about his bullying would be fired.

During the previous week, Camilla’s assistant Amanda McManus had shifted her attitude. On Monday she had told Robert Higdon, ‘I hate Michael. He’s not honest and he’s a liar. He should go,’ but by Thursday she was willing ‘to go through hell to help Camilla on Fawcett’s behalf’. Survival, she evidently realised, depended upon unquestioning sycophancy.

The crisis had been a failure of management. Unlike conventional executives, Lamport could not tell Charles to his face that his loyalty to Fawcett was unwise. Such outspokenness would guarantee his dismissal. Quietly, he implemented the royal wishes. Fawcett’s authority was restored, and indeed magnified. Outsiders seeking an appointment with Charles increasingly approached Fawcett in the hope that he would deign to be helpful.

The contrast between Charles’s management of his personal kingdom and his mother’s concern for the realm was captured soon afterwards at a meeting of the Way Ahead Group in Buckingham Palace’s cinema.

As he stood chatting with Simon Lewis, Lord Camoys and Michael Peat, Robin Janvrin felt particularly proud of his creation of the group back in 1993. The four officials who had taken over the queen’s private office presented themselves as the new generation. In the past, Richard Aylard had simply kept the show on the road, while Robert Fellowes had been the firefighter. Now Janvrin, jokingly dubbed ‘the angry young man’ by David Airlie, stood before the royals under a metaphorical banner that read ‘We must have change.’ In his opinion, his opponents offered the ‘doctrine of unripe time’. Gathering the key members of the royal family together, he suggested, could resolve their differences, and would help them plan the monarchy’s response to the tabloids’ intention to scratch open the raw scars once again as the first anniversary of Diana’s death approached.

The queen, Philip and their four children arrived, kissing each other warmly without betraying any tensions. Despite their rivalries, the family ostensibly remained friends. Janvrin’s tripwire was Charles. The heir’s natural stubbornness, he hoped, would melt away in the face of his unemotional presentation of the advantages of reform.

In anticipation of the meeting, Lewis had sent the queen a report based on a Mori opinion poll. Commissioned by Janvrin, it had been opposed by Michael Peat as a waste of money. Its conclusions were the basis of Lewis’s one-hour presentation, complete with slideshow.

The six royals understood the sharp difference between the public’s attitude towards the monarchy and towards other British institutions. Each of the four nations and each age group had differing attitudes towards the family. To rebuild its popularity, Lewis advised, over the coming months they should take up a dual focus: on Scotland, and on forging a relationship with Britain’s youth.

The queen agreed. Janvrin proposed to lighten the tone of her official tours. Meetings with the uniformed county lord lieutenants would be reduced, and instead she would visit schools, a pub, take a ride in a London taxi, sign a Manchester United football, walk past a McDonald’s and meet some of the homeless and unemployed. The queen agreed again. To placate Anne’s anger that Charles was occupying too much of the spotlight, Janvrin proposed that the princess should be given special status in Scotland. The queen’s continuing approval encouraged the Blairite modernisers.

The next item was the Jubilee, four years in the future. ‘What will we do?’ asked Philip, starting a family discussion. The unity crumbled. Charles wanted to reduce the numbers of the family appearing on the Buckingham Palace balcony and the number of teenage royals entitled to police protection. His particular targets were Andrew’s two daughters, Beatrice and Eugenie. Then he mentioned in a critical tone the commercial activities of his two brothers. ‘Enough has been done,’ interrupted Philip. He urged the queen to protect tradition. Amid that discord, the meeting ended.

Nervous that the Mori poll’s findings would provide negative headlines, Janvrin forbade Lamport to show the results to Bolland. Regardless, Charles ensured that some critical figures were leaked to the Sunday Times, partly because he disliked the idea of the Way Ahead Group and the meetings, and partly because he wanted to assert his primacy over his siblings. ‘I’m the Prince of Wales and they’re not,’ he said. To reassert his status still further, he opposed Janvrin’s plan to improve cooperation between himself and his mother by merging the two palaces’ press offices and appointing Lewis at their head. He ridiculed the idea of a New Labour spin master overseeing ‘The New Monarchy’ and prying into his plans, not least because he was becoming disenchanted with the government.

That disenchantment would soon become public knowledge. In June 1998, Charles declared war on Labour’s support for genetically modified crops. In an interview with the Daily Telegraph, he warned that scientists were straying into ‘realms that belong to God, and God alone’, and questioned whether man had the right to ‘experiment with and commercialise the building blocks of life’. Genetic food engineering to produce long-life tomatoes, pest-resistant crops and soya beans with added protein would, he asserted, create a man-made disaster and deprive the public of organic foods. Consumers should consider the profits made by the manufacturers of the pesticide DDT and asbestos – both once hailed as scientific wonders but eventually proven to have potentially fatal side-effects – as an omen for GM crops.

Forewarned about the prince’s attack, Blair told Alastair Campbell, ‘We’re going to have running troubles with Charles because on many issues he’s more traditional than the queen.’ In the hope of securing an armistice, the two drove to Highgrove in the September sunshine. By then, Blair’s acerbic spokesman had become hostile towards Charles. The begrudging agreement by Highgrove’s staff that Campbell could use the swimming pool – which he found ‘a bit manky and with too many leaves floating around’ – did little to improve his temper. The visit, he declared, was ‘a journey back so far back in time it felt extra-planetary’.

After his swim, Campbell was offered lunch in the staff canteen. Inside the house, Blair was sharing a meal with his host, who for over fifteen years had championed a number of unfashionable causes, a category which until recently had included environmental protection. Ignoring Tory ministers’ mockery, he had warned about the failure to combat acid rain, protested against farmers burning straw, demanded a ban on CFC gases to protect the ozone layer, forecast ‘the problems and dangers of possibly catastrophic climate changes through air pollution’, warned about plastic bags and bottles polluting the seas, and lamented the mass extinction of species as a result of the loss of tropical forests. All his campaigns, Charles believed, had been dismissed by lethargic politicians and ignorant officials. Almost without exception, they had ignored the threats to mankind. The latest of that breed, he suspected, was Tony Blair.

Dealing with the royal family was difficult for any politician. To have a direct conversation with someone with unusual preoccupations was inevitably uphill, but a dialogue with Charles was especially perilous. The various self-deprecating cartoons of the prince in the guest lavatory did not signal democracy in the household, but rather the owner’s vanity. Blair understandably wanted to know in advance where any discussion would end. There was no answer. His caution proved justified when four weeks later a newspaper published an account of their meeting. Blaming the ‘national disgrace’ of using unproven technology for ruining farmers in ‘an arms race against Nature’, Charles publicly urged Britons to boycott GM crops – or, as environmental campaigners described them, ‘Frankenstein foods’.

The indiscretion surprised Blair. Not only did Charles explicitly oppose government policy, but, as Mark Bolland witnessed, ‘he didn’t care’ about a public disagreement. Far from upholding traditional royal impartiality, Charles thought only about his ‘duty’, discounted the government’s problems and ignored the danger of his overt prejudice. Blair asked Peter Mandelson to caution the prince, and in a telephone call from New York, Mandelson, who believed that Charles’s views ‘were anti-scientific and irresponsible in the light of food shortages in the developing world’, told the prince that his remarks were ‘unhelpful’. He congratulated himself that his royal hearer did ‘tone down his public interventions on the subject’, but his success was temporary.

Charles now switched his attention to Camilla. The discretion about their relationship, he decided, had to end. Camilla wanted to be seen with Charles at the theatre, go on holiday with him openly, and establish a bond with his sons; but a relationship akin to marriage could be considered only after the public had accepted her. Her principal opponents remained the queen and the queen mother. Neither would allow her to be in the same room with them, yet both welcomed her ex-husband to receptions, race meetings and house parties. To show their affection for him, a palace official had lobbied that he should be promoted from colonel to brigadier, and appointed director of the Royal Army Veterinary Corps. Both suggestions were approved. In protest, the army’s senior vet resigned, a rare exception to the universal enchantment with the new brigadier.