По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

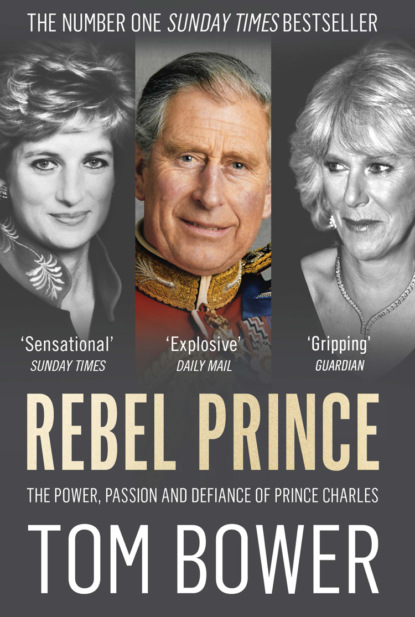

Rebel Prince: The Power, Passion and Defiance of Prince Charles – the explosive biography, as seen in the Daily Mail

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Charles could not understand the queen’s sympathy for Diana and her antagonism towards Camilla. After all, Diana’s theatrics in the media had damaged the family, while Camilla had remained utterly discreet. Why, he asked, could his mother not approve of a traditional Englishwoman who loved the countryside and horses? Camilla’s case had been raised by the Earl of Carnarvon, the queen’s racehorse trainer and close friend. His efforts as a go-between having proved unsuccessful, he switched to the queen’s side. Princess Margaret had also tried on Charles’s behalf, but her sister had replied that she wanted neither to meet nor to talk about Camilla. Few understood the reason for her disapproval: the queen was nervous that the character exposed in the Camillagate tapes was that of a shrewd mistress. ‘Oh darling, I love you,’ Camilla had gushed. The much less savvy Diana never made such over-the-top declarations. Carried away by a gust of tenderness towards himself, Charles complained that neither Diana nor his mother ever sympathised with his needs.

Exasperated by what he termed an intolerable situation, and egged on by Princess Margaret, he approached his mother late one night while he was staying at Balmoral and asked that she soften her antagonism so he could live openly with Camilla. He assumed that the queen, who rarely interfered or directly forbade anything, even the Dimbleby project, would not object.

But on that evening she had had several Martinis, and to Charles’s surprise she replied forcefully: she would not condone his adultery, nor forgive Camilla for not leaving Charles alone to allow his marriage to recover. She vented her anger that he had lied about his relationship with what she called ‘that wicked woman’, and added, ‘I want nothing to do with her.’ Met with a further hostile silence, Charles fled the room. In his fragile state, her phrase – ‘that wicked woman’ – was unforgettable. Tearfully, he telephoned Camilla. She in turn sought consolation from Bolland, who later received a call from Charles with a verbatim report of his conversation with his mother. Shortly after the confrontation, an opinion poll found that 88 per cent of Britons opposed their marriage.

Not everything was bad news. Good fortune had pushed disagreeable characters to one side. ‘Kanga’ Tryon, Charles’s Australian former girlfriend, had died suddenly after a period of declining health, so removing one potential source of mischief; and Charles Spencer, Diana’s brother and an outspoken critic of Charles, had damaged his own reputation with an acrimonious divorce.

With two irritants removed, Charles decided to defy the queen and take a small but critical step towards Camilla’s acceptance. On 12 June 1998 he introduced Camilla to William at St James’s Palace. On the eve of his sixteenth birthday, his son assumed that the twenty-minute meeting would remain private, but in what turned out to be a genuine mistake Camilla’s assistant leaked it. In the tabloid storm that followed, Camilla found herself implicated in Diana’s death. To fight back, she and Bolland arranged that Stuart Higgins, a former editor of the Sun, would write a flattering article in the Sunday Times. At the recent Way Ahead Group meeting, Higgins wrote, the royal family had agreed as a priority to normalise Camilla’s position in the royal household. That was inaccurate: she had not even been mentioned during that summer’s meeting. But the distortion, approved by Charles, chimed with his campaign during the weeks before his fiftieth birthday. In Downing Street no one was fooled. Alex Allan, the prime minister’s private secretary, had written about the obstacles that faced Charles and Camilla, and concluded that nuptials were unlikely.

Disregarding the resentment towards them, Charles, Camilla and Bolland met at Highgrove to construct another campaign. The first hurdle was to demythologise Diana by radically changing her image and portraying her as a manipulative hysteric. The vehicle was to be Penny Junor’s book. The author’s plan had changed since Diana’s death. Instead of focusing on Camilla, Junor intended to shatter the image of the late Princess of Wales as the put-upon innocent and to cast Charles as a helpless victim, with neither parents nor friends to provide support. The publication of Charles: Victim or Villain? was timed to coincide with his birthday in November. Enriched by dramatic disclosures, the book described Diana as ‘sick, irrational, unreasonable and miserable’ on account of her bulimia, and therefore an unbalanced and unfaithful woman who compelled Charles to return to his true love. ‘[Charles] had to put up with years of tantrums and abuse,’ wrote Junor. He ‘cut his friends out of his life at Diana’s insistence, and even gave away the dog he loved in an effort to make Diana happy’.

Junor questioned Diana’s sanity by quoting a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, arrived at by scouring the internet, for an explanation of her behaviour. Charles supported the diagnosis: ‘We must get this out,’ he said. In a further attempt to damage Diana’s reputation, Junor wrote that the princess had been the first to commit adultery. In a series of revelations, the book described Diana bombarding Oliver Hoare, a married art dealer with whom she was having an affair, with anonymous telephone calls. Diana had denied the relationship, even though it had lasted some months, but accurately blamed a mischievous schoolboy for the nuisance calls. The book also unmasked her affair in 1986 with Barry Mannakee, one of her police protection officers, as well as confirming her long amour fou with James Hewitt.

Junor’s book shocked Diana’s loyalists, who were outraged by the complicity of Charles’s staff. Throughout his life, Charles had never been able to give and take. Thinking only about himself, he resented suggestions of equality with his wife. Diana’s supporters recalled his jealousy of her popularity during their first visit to Australia in 1983. Junor, they noted, had omitted from her book the argument between Charles and Diana on their plane after it landed at Alice Springs about who should go down the steps first (Charles won). Later that day, the roaring welcome that the children in the crowds gave to Diana had infuriated the prince. ‘I should have had two wives and just walked in the middle,’ he said grumpily to an aide.

At first, Diana had not grasped her husband’s feelings of resentment, and when she did, she fuelled them. At a music college during their second visit to Australia in 1988, Charles scraped a bow over a cello, whereupon Diana glided across to a piano to play perfectly a favourite piece by Grieg. To the media’s bemusement, Charles looked crestfallen. She had stolen his show. While she glowed as the global icon, he was the middle-aged man typically photographed on a Scottish estate, dressed in tweeds, resting against a shepherd’s crook.

To combat that image, Junor described incidents that appeared to be fuelled by Charles’s desire for revenge. The book mentioned the speculation about Diana’s death threats to Camilla in telephone calls, and her attempted suicide while pregnant with William. However, she omitted any description of Diana’s misery during her honeymoon on Britannia after she heard Charles talking on the phone with Camilla, conversations also overheard by the ship’s crew. Nor was there any mention of Diana’s acts of vindictiveness: that Charles had entered their suite on the yacht to find her in tears cutting up a watercolour he had just completed (a version of that episode would be included in Junor’s admiring biography of Camilla in 2017). The book had only minimal sympathy for the neglected twenty-year-old bride. Undoubtedly, Diana had fabricated and exaggerated Charles’s drift towards adultery, but equally Junor did not reveal the complete truth about his relations with Camilla. In 1973, while waiting for Andrew Parker Bowles’s proposal, Camilla had many admirers but only two other serious boyfriends. Andrew, she knew, was not passionately in love with her, but he was charming, good-looking and well-connected. As a close friend would say, he was a thirty-three-year-old officer who needed to marry. Camilla was the best of the bunch as a potential wife, fun and good with people, yet he expected his bachelor life to go on as before.

One week before their wedding, Charles had telephoned Camilla from his Royal Navy ship. Sounding desperately lonely, he asked whether she was sure about marrying, but did not propose himself. After ending the call, Camilla immediately repeated the conversation to her fiancé. They both laughed, knowing that Charles felt isolated and depressed as a result of his sister Anne’s marriage to Mark Phillips.

In hindsight, even Andrew Parker Bowles would realise that he could never have been loyal to Camilla. Despite his Catholicism and his intention to be a good husband, he started his adulteries earlier than he had anticipated. Not long after their wedding, Camilla discovered her husband’s affairs. She was upset but resigned. Her feelings for Charles changed only after Andrew abandoned her during long foreign trips. Even then, she was not genuinely in love with Charles. Many friends were convinced that she continued to love Andrew, but was flattered by the prince’s attentions.

The much-trumpeted newspaper serialisation of Junor’s book was accompanied by a statement from Charles’s office that he had ‘not authorized, solicited or approved’ it. Junor would confidently contradict that assertion, and offered details of the help she had received, with Charles’s authority, from his staff.

For his part, Mark Bolland denied providing any material critical of Diana, but Robin Janvrin did not believe him. In his opinion, Bolland’s fingerprints were all over the book, which marked a sharp escalation of the campaign to make Charles’s relationship with Camilla acceptable to the British public. As another Buckingham Palace official sniped, Charles reigned over ‘an old-fashioned court filled with a sack-full of snakes’. In the midst of the Junor headlines, ITV reported that Charles would be ‘privately delighted’ if the queen abdicated. Shortly after, following an unrecorded hour-long conversation with the prince, Gavin Hewitt reported on the BBC that Charles was frustrated by Buckingham Palace’s withholding of power. Janvrin was incandescent. Not only were the tabloids using Junor’s book to reignite stories about Charles’s adultery, but simultaneously his birthday party at Highgrove for 350 people was spawning headlines about the queen’s ‘snub’ – her rejection of his invitation because of Camilla’s presence. Further to enhance his client’s reputation, Bolland circulated a comment from Mario Testino, Diana’s favourite photographer, who when asked whether Camilla should be queen, replied, ‘Definitely. Have you met her? She’s a great person. If you meet her, you want to hang out with her.’

In Janvrin’s opinion, Bolland’s operation was out of control. Charles contacted his mother from Bulgaria to protest his innocence about the abdication report. His denial was suspicious to those around the queen who knew of his impatience to be king, while Bolland’s declaration of innocence was discounted. The tabloid headline-writers were ecstatic.

Janvrin’s anger reflected the queen’s bewilderment. The monarchy, her advisers believed, did not need spin like Downing Street. During a visit to St James’s Palace, Janvrin told Stephen Lamport that there was no reason for Charles to campaign so energetically to promote Camilla. Bolland was acting as a free agent rather than as part of the team, and by standing between the tabloids and the royals he risked getting ‘run over’ for his misjudgement.

Lamport could have honestly pleaded ignorance. He was unable to manage Bolland, who with the two principal plotters excluded him from their discussions. To keep face, he volunteered that, whenever relevant, Janvrin would be kept informed about Charles’s plans, and that his opinion would be taken into account. He added that Bolland might not be a desirable presence, but he was effective, and said that Charles would like to introduce Janvrin to Camilla, who by chance was in the building. ‘Certainly not,’ replied Janvrin – any meeting would need the queen’s permission. With that, he walked out of the palace. Charles was furious.

In an effort to calm the storm, David Airlie took Bolland for lunch at White’s, his club in St James’s. The older man counselled that things were done in a certain way, and that Her Majesty would be grateful if he could stick to the rules. In his defence, Bolland contended that Stuart Higgins, acting as an adviser to ITV, had distorted a conversation between them. ‘Stuart screwed me up,’ he said, and refused to speak to the former journalist again. ‘But it was a tricky week,’ he admitted.

Reports of the lunch at White’s reached Camilla. She feared that her agent was ‘moving to the dark side’ and taking orders from Buckingham Palace. Bolland rushed to reassure her, and in turn Charles, who on reflection decided there was no alternative but to treat Janvrin as an ally. Bolland was dispatched to tell the courtier about a weekend party Charles was hosting at Sandringham. Among the guests would be Jacob Rothschild, Peter Mandelson and Susan Hussey, a trusted friend and lady-in-waiting to the queen. Under pressure from Camilla, Charles agreed that she should also be invited. The tabloids would undoubtedly highlight her presence in the queen’s home despite the monarch’s disapproval. To Bolland’s relief, instead of protesting, Janvrin consulted the queen, who agreed that as it was a private party, she did not need to be involved.

Janvrin also averted another argument, this time about Michael Fawcett. Charles had insisted that Fawcett supervise the preparations for his official birthday party at Buckingham Palace. The queen, who still disliked Fawcett, objected, but Janvrin persuaded her that he ‘must be kept onside’ because of his importance to Charles.

Shortly after this, the plotters delivered their coup: a major birthday party for Charles, this time at Highgrove, with Camilla on public display. She was duly photographed arriving at the party looking regal, having prepared herself for the event with a week’s cruise on Yiannis Latsis’s yacht in the Aegean. Charles presented himself as a man who had found peace with the woman he loved. The event was arranged by Emilie van Cutsem, a socially ambitious Dutchwoman, the wife of an old friend of Charles from his Cambridge days. Having cared for William and Harry during the worst years of the prince’s marriage, she was distrusted by Camilla, but that undercurrent went unnoticed during the riotous celebration. However, what was not so easy to overlook were the absentees: of the royal family only Princess Margaret turned up. None of Charles’s three siblings accepted his invitation.

His close friends were divided. Some supported him for ‘pushing at the right pace’. Others, mindful of their relations with the queen and fearful of losing invitations to Sandringham and Balmoral, spoke loudly about the advantage of caution. This group included Nicholas Soames; Emilie van Cutsem’s husband Hugh; Charles Lansdowne, owner of Bowood House in Wiltshire near Ray Mill, Camilla’s home; Piers von Westenholz, an antique dealer; and Charles and Patty Palmer-Tomkinson. One malicious critic told of Patty’s panic during a motorway journey. Charles had telephoned to say he was unsure whether he could be present at her daughter Santa’s wedding. Patty pleaded, and finally Charles and Camilla agreed to come, but arrived separately. In the background hovered Annabel Elliot, Camilla’s sister. The Elliots protected Camilla from Soames and the Palmer-Tomkinsons. Their vigilance, sniped some, stemmed from their fear of losing influence. Everyone seemed to have mixed motives, but few forgot Diana’s carping about the ‘brown-nosers’ around Charles, whom she called ‘oilers’.

Two nights later there was yet another birthday party, this time at Hampton Court. Camilla was there too. Early the next morning, Charles left for Sheffield to meet a group of disadvantaged young people. Such visits not only placated his critics but also reflected his genuine interest in the young. The following evening, nearly a thousand guests, including Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, arrived for Charles’s official birthday party at Buckingham Palace. Camilla was not among them.

‘Everyone here,’ said the queen, turning to her son during her speech, ‘has benefited from the breadth of your interests and from your vision, compassion and leadership.’ Listening alongside Blair was Peter Mandelson. Both must have appreciated Charles’s political talent in his endearing reply to ‘Mummy’, concealing his true feelings about the absence of his mistress.

Six weeks later Mandelson, newly appointed as minister for trade and industry, was forced to resign after failing to reveal a loan from Geoffrey Robinson, a Treasury minister, to help buy his house while Robinson was under formal investigation by his own department. As Mandelson sat tearfully in his ministerial office listening on the telephone to Blair’s fatal reprimand, Alastair Campbell, who was in the room with him, noticed a Christmas card from Charles occupying pride of place on his desk. Campbell dismissed the prince as an interfering, privileged fool, but Mandelson defended him, grateful for Bolland’s reassurance that his relationship with Charles would be unaffected by the scandal. Charles could not afford to cast aside a valuable if tainted supporter just as he was heading for another showdown with the media.

Thanks to Bolland’s introductions, the prince had established personal relations with several newspaper editors. After receiving invitations to the birthday party at Hampton Court, they published positive articles to ‘build him up’ and prove that the Camilla campaign had not been harmed by the queen’s boycott. Just two days after the party, several papers published photographs of Camilla on horseback, with her approval.

The next task was to begin repairing the damage caused by Penny Junor’s wholesale damnation of Diana, an assault Charles half-regretted. Although Junor had written that he remained in love with Diana and prayed for her every night, his denial of any involvement with the book had not convinced anyone. In mitigation, he pleaded that his reputation would be restored by the publication of his personal documents long after his death. When that did little to silence the criticism, he was persuaded to release copies of his handwritten letters to ‘a close relative’ to the Daily Mirror. Apparently composed during their fractious journey around Australia in 1983, the letters professed his love for Diana. He especially admired ‘her wonderful way of dealing with people. Her quick wit stands her in excellent stead, particularly when silly people ask what she has done with William or why hasn’t she brought him etc.’ He went on, ‘Diana has done wonderfully throughout this gruelling exercise and has won everyone’s heart – including some of the most hard-bitten Aussie “knockers”.’ He added, ‘I do sometimes worry so much about what I have landed her in at such an impressionable age. The intensity of interest must be terrifying for her.’

In another letter, written a year later, when the couple’s marriage was already under severe strain, Diana had confessed to the same ‘relative’: ‘I can’t stand being away from him.’ She wrote that Charles’s early return from a fishing trip was a ‘wonderful surprise’, and in yet another letter described a ‘marvellous’ time at Balmoral. Since that contradicted the recollection of her friends, who recalled her permanent misery in Scotland, some suspected that an unseen hand had fabricated all the letters as a way to promote Charles.

On the following day the Mirror published more excerpts from letters apparently written to the same ‘close relative’ by Charles in 1988 and 1989, three years after the marriage’s collapse. The prince admitted to depression and insecurity because his public work had little impact and his arguments were ignored. ‘Sometimes I am terrified by the expectations people have of me and of the immense responsibility thrust on me,’ he confided. ‘I sometimes feel that I am going to let people down, however hard I try … I sometimes wonder why we rush about so much or why I, in particular, feel I have to solve all the nation’s problems single-handed? It must be a basic weakness of character which advancing age may cure!’ That was Charles’s genuine voice. The doubts about the authenticity of the early letters arose only after Mark Bolland confessed honest ignorance about the identity of the ‘close relative’ who released them to James Whitaker, the Mirror’s royal correspondent. Whitaker, loyal to Charles, added a flourish about the lonely prince’s virtues: ‘Listening to Charles talking about his lack of self-esteem, one could easily cry for him … The important thing to understand about this tortured, complex man is that he does feel he has the cares of the world on his shoulders. He tries so hard to deliver, to do his duty as he thinks is right.’

The letters’ publication gave Charles confidence to use the media more aggressively. ‘Let’s risk the biscuit,’ he told Bolland after several newspapers published photographs of his visit with Camilla to a London theatre. The positive comments encouraged him once again to confront his mother over their relationship, only this time in public.

In the weeks after his birthday, they had not spoken. The atmosphere at Sandringham over Christmas must have been frosty. Now he wanted to stage a spectacular event to establish Camilla as his permanent partner. He needed a photograph that was neither snatched nor contrived. The ideal moment would occur on 29 January 1999, seventeen months after Diana’s death, when Annabel Elliot celebrated her fiftieth birthday at the Ritz hotel in Piccadilly.

‘The prince must come,’ she wailed. ‘It would be terrible if he didn’t.’

‘Let’s lance the boil,’ agreed Bolland, arguing that snatched photographs by the paparazzi were poor-quality and rewarded only the photographer. In what Bolland regarded as Charles’s ‘cunning and tough’ directives, it was agreed to transform the couple’s exit from the hotel into a historic milestone.

A tip to a Daily Mail diarist revealed Charles’s ruse. ‘Will they arrive or leave together?’ the diarist was prompted to ask in his column. Bolland then telephoned Arthur Edwards, the Sun’s royal photographer, to draw attention to the item. From there, reaction snowballed. The first of over two hundred photographers and TV crews staked out their positions opposite the Ritz three days before the event. They were allowed to block the pavement and the street to record a romance that according to legend had started twenty-seven years earlier. The royal command overrode any official opposition from the police or Westminster council. On the night, anxious newspaper editors delayed printing their main editions while journalists called Bolland – dining with the editor of the Sunday Times in a City restaurant – for reassurance that the ‘historic’ appearance would indeed happen.

Just before midnight, Charles and Camilla stepped from the hotel’s entrance amid a thunderclap of flashing lights, and posed briefly before getting into a car. Dressed in a sombre suit, the prince looked serious while Camilla appeared radiant. The results exceeded Charles’s expectations. Across the world, the photographs were interpreted even more positively than he had planned. ‘At Last’ blared the Mirror. ‘Meet the Mistress’ was the Sun’s less fawning headline. There was unanimity about the fallacy of previous predictions. Over the past decade, so many clever people had forecast that the next stage would never happen: first, few believed that Charles and Diana would separate, then that they would divorce. Next, they discounted an enduring public relationship between Charles and Camilla. Now, relying on Buckingham Palace’s spokesman, the same soothsayers dismissed the idea of Charles marrying Camilla, and ridiculed the notion of Camilla eventually becoming queen. The queen remained silent, actively supported by the queen mother during their regular conversations. Charles was stubborn. He had pushed recognition one step further, but he did not underestimate the continuing obstacles before he could finally override his mother’s wishes. The media would be his weapon.

That same media which for years he had cursed for being intrusive, and for cynically disbelieving his denials of adultery, had now become his ally. Rather than revile their misrepresentations, he encouraged Mark Bolland to welcome more editors to St James’s Palace and to drip-feed stories: about Camilla wearing a brooch from him as a token of love; about the smiles towards the couple during further visits to the theatre; and, to please the Sun, a visit to the Soho gay pub that had been nail-bombed by a neo-Nazi fanatic.

Just before flying to New York in 1999 to promote Camilla, Bolland met the senior editors of Rupert Murdoch’s tabloid newspapers at Wapping, News Corporation’s London headquarters. Both the Sun and the News of the World continued to reflect their readers’ love for Diana and their dislike of Charles and Camilla. Winning over working-class women – who made up many of the newspapers’ readers – was a priority. Bolland’s hosts were Les Hinton, the corporation’s chief executive, and Rebekah Wade, an editorial director at the Sun. Both distrusted the royals’ spokesmen. Too often their journalists had approached the palaces’ media officials for a comment about a murky revelation only to be rebutted with an outright lie. All that, Bolland promised, would change. He would speak the truth, not least because he needed the Murdoch press’s support against the queen. ‘We were turning up the gas,’ he would later say, ‘because the queen was unmovable.’

Nine months after the New York trip, in early June 2000, Bolland returned to Wapping for lunch with Rebekah Wade, who by then had been introduced to Charles and Camilla. Using Wade as an ally posed no difficulty for Bolland, but the alliance led to a standoff between Wade and the normally unflappable Robin Janvrin, who was surprised when she asked, ‘When is Her Majesty going to give the green light for Charles and Camilla to marry?’

‘Public opinion is against it,’ he replied.

‘Well,’ said Wade, ‘we would have to go against the queen, because our readers are for Camilla. The queen should think again.’ She added, ‘We might move to support an abdication and let Charles take over.’

Days later, the headline on the Sun’s front page blared ‘Marry Her, Sir’. Inside the same edition was a prominent report, with photographs of Charles, dressed in military uniform, taking the salute in France for seven hundred Dunkirk veterans on the sixtieth anniversary of their evacuation. ‘This is very much the Dunkirk spirit,’ he told them. That weekend was a victory for Charles, Camilla and Bolland; they were starting to dictate the agenda.

In Buckingham Palace, the normally even-handed Janvrin was shocked. The Sun’s threat to campaign against the queen was typical of the divisiveness masterminded by Bolland. Ever since he had been hired, the battle between the palaces had turned into a public brawl.

In June 1999, a poll had shown that 57 per cent of the British public supported a marriage between Charles and Camilla, up from 30 per cent two years earlier. More relaxed than previously, Charles now entered receptions looking confident – but also, Roy Strong observed, unfashionably ‘Hanoverian’ and often surrounded by courtiers chosen apparently because they were shorter than him. Tony Blair also noticed Charles’s new self-confidence. Anji Hunter, his special assistant, was sent to ask Bolland if Charles was intent on marrying Camilla. Officially, Hunter was instructed not to interfere, but privately she told Blair about Charles’s resolve.

To neutralise the Earl of Carnarvon’s support for the queen’s opposition to his remarriage, Charles recruited Angus Ogilvy, the brother-in-law of Lord Airlie, to negotiate on his behalf. Ogilvy was married to Princess Alexandra, a trusted cousin of the queen. Briefed by Charles, he relayed to the queen that her son would not compromise or surrender. This was not the rebellion of a petulant prince, but reflected a man unafraid, even delighted, to challenge authority.

6

Body and Soul (#ulink_eddb16a5-8859-5602-90c2-578fb73ed45c)

Charles wanted the monarchy to champion unfashionable causes. His most potent weapon to promote his status was his charities, about twenty organisations engaged in a diverse range of activities helping tens of thousands of people and many valuable causes every year. Charles had decided that only being forthright would guarantee an impact, and his charities gave him a powerful platform. Stoking controversy risked his being accused of breaking constitutional expectations of political impartiality, but the brave savoured risks. Ever since the Prince’s Trust had been created in 1976, an initiative of pure altruism, financing his charities had become a preoccupation. However, Charles and his officials did not anticipate the financial problems that would accumulate.

Charles’s insatiable appetite for money for his charities attracted Manuel Colonques, the founder of Porcelanosa, a Spanish tile manufacturer. Colonques had successfully promoted his company across the world by paying celebrities including Kevin Costner and George Clooney to endorse Porcelanosa’s expanding empire. One by-product of his philosophy – ‘The more you give, the more you receive’ was his motto – was regular features in ¡Hola!, the Spanish Hello! magazine.

Always searching for new superstars, Pedro Pseudo, a Porcelanosa director, had hit on Charles in the mid-1990s. In his efforts to meet the prince he approached Chrysanthi Lemos, the wife of a Greek ship-owner and a fundraiser for the Philharmonia Orchestra in London. Lemos had no difficulty persuading Pseudo to give money to the orchestra; in return he would receive an invitation to its concert at Highgrove. Included among the audience were Luciano Pavarotti, Richard Branson, Donatella Versace and other celebrities. Lemos told Charles about Colonques’s enthusiasm for Charles’s charities, and after the concert Charles took the Spaniard and his party on a tour of his garden. ‘After that meeting,’ Lemos recalled, ‘Fawcett took over. I wasn’t needed any more.’ With Fawcett as intermediary, Charles hosted a party in 1998 at St James’s Palace to celebrate Porcelanosa’s twenty-fifth anniversary, and another to thank the company for a donation to the Prince’s Foundation. The pattern of selling access to himself funded Charles’s principal achievement. But this success had also bred embarrassing controversies.

In 1976 Charles’s office had telephoned the television journalist Jon Snow, interested in replicating Snow’s small charity for disadvantaged youths. ‘I want to make a difference,’ the prince explained. Together they invented the name ‘the Prince’s Trust’, with an initial fund of £7,471, Charles’s pay-off from the Royal Navy. Thereafter, fundraising by Tom Shebbeare, the trust’s chief executive, was uncomplicated. When Charles and Diana patronised a London pop concert, the charity received £1 million. With a minimum of red tape, the trust’s administrators were empowered to write out cheques for disadvantaged young people, to finance travel for an interview, or set up a business, even to remove tattoos. As its funds increased, the Prince’s Trust became noted for taking unusual risks. ‘If I don’t do it,’ Charles said purposely, ‘it won’t exist.’