По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

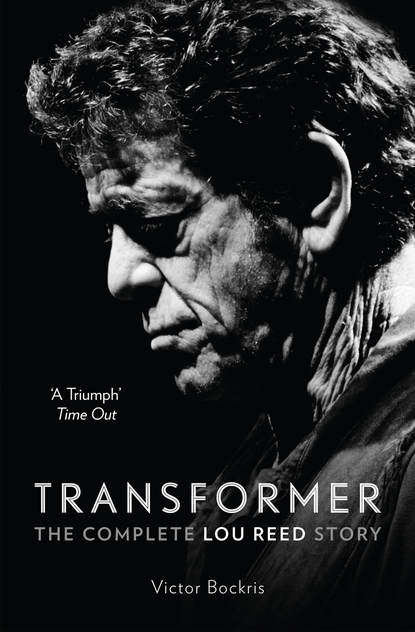

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Lou Reed

Nineteen fifty-nine was a bad year for Lou, seventeen, who had been studying his bad-boy role ever since he’d worn a black armband to school when the No. 1 R&B singer Johnny Ace shot himself back in 1954. Now, five years later, the bad Lou grabbed the chance to drive everyone in his family crazy. Tyrannically presiding over their middle-class home, he slashed screeching chords on his electric guitar, practiced an effeminate way of walking, drew his sister aside in conspiratorial conferences, and threatened to throw the mother of all moodies if everyone didn’t pay complete attention to him.

That spring, Lou’s conservative parents, Sidney and Toby Reed, sent their son to a psychiatrist, requesting that he cure Lou of homosexual feelings and alarming mood swings. The doctor prescribed a then popular course of treatment recently undergone by, among many others, the British writer Malcolm Lowry and the famous American poet Delmore Schwartz. He explained that Lou would benefit from a series of visits to Creedmore State Psychiatric Hospital. There, he would be given an electroshock treatment three times a week for eight weeks. After that, he would need intensive postshock therapy for some time.

In 1959 you did not question your doctor. “His parents didn’t want to make him suffer,” explained a family friend. “They wanted him to be healthy. They were just trying to be parents, so they wanted him to behave.” The Reeds nervously accepted the diagnosis.

Creedmore State Psychiatric Hospital was located in a hideous stretch of Long Island wasteland. The large state-run facility was equipped to handle some six thousand patients. Its Building 60, a majestically spooky edifice that stood eighteen stories high and spanned some five hundred feet, loomed over the landscape like a monstrous pterodactyl. Hundreds of corridors led to padlocked wards, offices, and operating theaters, all painted a bland, spaced-out cream. Bars and wire mesh covered the windows inside and out. Among the creepiest of these cells was the Electra Shock Treatment Center.

Creedmore State Mental Hospital. (Victor Bockris)

Into this unit one early summer day walked the cocky, troubled Lou. He was escorted through a labyrinth of corridors, unaware, he later claimed, that his first psychiatric treatment session at the hospital would consist of volts of electricity pulsing through his brain. Each door he passed through would be unlocked by a guard, then locked again behind him. Finally he was locked into the electroshock unit and made to change into a scanty hospital robe. As he sat uncomfortably in the waiting room with a group of people who looked to him like vegetables, Lou caught his first glimpse of the operating room. A thick, milky white metal door studded with rivets swung open revealing an unconscious victim who looked dead. The body was wheeled out on a stretcher and into a recovery room by a stone-faced nurse. Lou suddenly found himself next in line for shock treatment.

He was wheeled into the small, bare operating room, furnished with a table next to a hunk of metal from which two thick wires dangled. He was strapped onto the table. Lou stared at the overhead fluorescent light bars as the sedative started to take effect. The nurse applied a salve to his temples and stuck a clamp into his mouth so that he would not swallow his tongue. Seconds later, conductors at the end of the thick wires were attached to his head. The last thing that filled his vision before he lapsed into unconsciousness was a blinding white light.

In the 1950s, the voltage administered to each patient was not adjusted, as it is today, for size or mental condition. Everybody got the same dose. Thus, the vulnerable seventeen-year-old received the same degree of electricity as would have been given to a heavyweight axe murderer. The current searing through Lou’s body altered the firing pattern of his central nervous system, producing a minor seizure, which, although horrid to watch, in fact caused no pain since he was unconscious. When Lou revived several minutes later, however, a deathly pallor clung to his mouth, he was spitting, and his eyes were tearing and red. Like a character in a story by one of his favorite writers, Edgar Allan Poe, the alarmed patient now found himself prostrate in a dim waiting room under the gaze of a stern nurse.

“Relax, please!” she instructed the terrified boy. “We’re only trying to help you. Will someone get another pillow and prop him up. One, two, three, four. Relax.” As his body stopped twitching, the clamp was removed, and Lou regained full consciousness. Over the next half hour, as he struggled to return, he was panicked to discover his memory had gone. According to experts, memory loss was an unfortunate side effect of shock therapy, although whatever brain changes occurred were considered reversible, and persisting brain damage was rare. As Reed left the hospital, he recalled, he thought that he had “become a vegetable.”

“You can’t read a book because you get to page seventeen and you have to go right back to page one again. Or if you put the book down for an hour and went back to pick up where you started, you didn’t remember the pages you read. You had to start all over. If you walked around the block, you forgot where you were.” For a man with plans to become, among other things, a writer, this was a terrible threat.

The aftereffects of shock therapy put Lou, as Ken Kesey wrote in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, “in that foggy, jumbled blur which is a whole lot like the ragged edge of sleep, the gray zone between light and dark, or between sleeping and waking or living and dying.” Lou’s nightmares were dominated by the sad, off-white color of hospitals. As he put it in a poem, “How does one fall asleep / When movies of the night await, / And me eternally done in.” Now he was afraid to go to sleep. Insomnia would become a lifelong habit.

Lou suffered through the eight weeks of shock treatments haunted by the fear that in an attempt to obliterate the abnormal from his personality, his parents had destroyed him. The death of the great jazz vocalist Billie Holiday in July, and the haunting refrain of Paul Anka’s No. 1 teen-angst ballad, “Lonely Boy,” heightened his sense of distance and loss.

According to Lou, the shock treatments helped eradicate any feeling of compassion he might have had and handed him a fragmented approach. “I think everybody has a number of personalities,” he told a friend, to whom he showed a small notebook in which he had written, “‘From Lou #3 to Lou #8—Hi!” You wake up in the morning and say, ‘Wonder which of them is around today?’ You find out which one and send him out. Fifteen minutes later, someone else shows up. That’s why if there’s no one left to talk to, I can always listen to a couple of them talking in my head. I can talk to myself.”

At the end of the eight-week treatment, Lou was put on strong tranquilizing medication. “I HATE PSYCHIATRISTS. I HATE PSYCHIATRISTS. I HATE PSYCHIATRISTS,” he would later write in one of his best poems, “People Must Have to Die for the Music.” But in his heart he felt betrayed. If his parents had really loved him, they would never have allowed the shock treatments.

***

Lewis Alan Reed was born on March 2, 1942, at Beth El Hospital in Brooklyn, New York. His father, Sidney George Reed, a diminutive, black-haired man who had changed his name from Rabinowitz, was a tax accountant. His mother, Toby Futterman Reed, seven years younger than her husband, a former beauty queen, was a housewife. Both parents were native New Yorkers who in a decade would move to the upper-middle class of Freeport, Long Island. Lewis developed into a small, thin child with kinky black hair, buck teeth, and a sensitive, nervous disposition. By that time, his mother, the model of a Jewish mother, had shaped her beauty-queen personality into an extremely nice, polite, formal persona that Lou later criticized in “Standing On Ceremony” (“a song I wrote for my mother”). She wanted her son to have the best opportunities in life and dreamed that one day he would become a doctor or a lawyer.

The house in Brooklyn where Lou was born. (Victor Bockris)

The emotional milieu that dominated Lewis’s life throughout his childhood was a kind of suffocating love. “Gentiles don’t understand about Jewish love,” wrote Albert Goldman in his biography of one of Lewis’s role models, Lenny Bruce. “They can’t grasp a positive, affectionate emotion that is so crossed with negative impulses, so qualified with antagonistic feelings that it teeters at every second on a fulcrum of ambivalence. Jewish love is love, all right, but it’s mingled with such a big slug of pity, cut with so much condescension, embittered with so much tacit disapproval, disapprobation, even disgust, that when you are the object of this love, you might as well be an object of hate. Jewish love made Kafka feel like a cockroach …”

In the opinion of one family friend, “Lou’s mother had the Jewish-mother syndrome with her first child. They overwatch their first child. The kid says watch me, watch me, watch me. You can’t watch them enough, and they’re never happy, because they’ve spent so much time being watched that’s what they expect. His mother was not off to work every morning, the mothers of this era were full-time mothers. Full-time watchers. They set up a scenario that could never be equaled in later life.”

When Lewis was five, the Reeds had a second child, Elizabeth, affectionately known as Bunny. While Lou doted on his little sister, her arrival was also cause for alarm. His mother’s love had become a trap built around emotional blackmail: first, since the mother’s happiness depends upon the son’s happiness, it becomes a responsibility for the son to be happy. Second, since the mother’s love is all-powerful, it is impossible for the son to return an equal amount of love, therefore he is perennially guilty. Then, with the arrival of the sister, the mother’s love can no longer be total. All three elements combine to put the son in an impossible-to-fulfill situation, making him feel impotent, confused, and angry. The trap is sealed by an inability to talk about such matters so that all the bitter hostility boiling below the surface is carefully contained until the son marries a woman who replaces his mother. Then it explodes in her face.

Goldman could have been describing Reed as much as Bruce when he concluded, “The sons develop into twisted personalities, loving where they should hate and hating where they should love. They attach themselves to women who hurt them and treat with contempt the women who offer them simple love. They often display great talents in their work, but as men they have curiously ineffective characters.”

The Reeds moved from an apartment in Brooklyn to their house in Freeport back in 1953—the year before rock began. Freeport, a town of just under thirty thousand inhabitants at the time, lay on the Atlantic coast, on the Freeport and Middle Bays—protected from the ocean by the thin expanse of Long Beach. The town, one of a thousand spanning the length of Long Island, was designed and operated around the requirements of middle-class families. Though just forty-five minutes from Manhattan by car or train, it could have been a lifetime away from Brooklyn, the city the family had just deserted. In fact, with well-funded parks, beaches, social centres, and schools, Freeport was suburban utopia. Thirty-five Oakfield Avenue, on the corner of Oakfield and Maxon, was a modern single-story house in a middle-class subsection of Freeport called the Village. Most of the houses in the neighborhood were built in colonial or ranch style, but Lewis’s parents owned a house that, in the 1950s, friends referred to as “the chicken coop” because of its modern, angular, single-floor design. Though squat and odd from the outside, it was beautifully laid out and comfortable, furnished in a 1950s modern style. It also had a two-car garage and surrounding lawn perfect for children to play on. In fact, the wide, quiet streets doubled as baseball diamonds and football fields when the local kids got together for a pickup game. Their neighborhood was for the most part upper-middle class and Jewish. The idea of urban Jewish ghettos had become as abhorrent to an increasingly powerful American Jewish population as it was to the continuing wave of European Jewish immigrants. Many Jewish families who had prospered in postwar New York had moved out of the city to similar suburban towns to get away from the last vestiges of the ghetto, and to create for themselves a middle-class life that would Americanize and integrate them. The resulting migration from New York to Long Island created a suburban middle class in which money was equated with stability, and wealth with status and power.

After graduating from Carolyn G. Atkinson Elementary and Freeport Junior High, in the fall of 1956, Lewis and his friends began attending Freeport High School (now replaced by a bunkerlike junior high). A large, stone structure, on the corner of Pine and South Grove, with a carved facade and expanse of lawn, the school resembled a medieval English boarding school like Eton or Rugby. It was a ten-minute walk from Oakfield and Maxon through the tree-lined neighborhood of Freeport Village and just over the busy Sunrise Highway. “I started out in the Brooklyn Public School System,” Lou said, “and have hated all forms of school and authority ever since.”

Lewis was surrounded by children who came from the same social and economic background. His closest friend, Allen Hyman, who used to eat at the Reeds’ all the time and lived only a block and a half away, remembered, “The inside of their house was fifties modern, living room and den. At least from sixth grade on my view of his upbringing was very, very suburban middle class.”

The area has a history of fostering comedians and a particular type of humor. Freeport in the twenties was a clam-digging town with an active Ku Klux Klan and German-American bund in nearby Lindenhurst. In the thirties and forties, it attracted a segment of the East Coast entertainment world, including many vaudeville talents. The vaudevillians brought with them not only their eccentric lifestyles and corny attitudes, but the town’s first blacks, who initially worked as their servants. By the time the Reeds got there, the show people were adding their own artistic bent to the town’s musical heritage. Their immediate neighbours included Leo Carrillo, who played Pancho on the popular TV show The Cisco Kid, as well as Xavier Cugat’s head marimba player and Lassie’s television mother, June Lockhart. Guylanders (Long Islanders) refuse to be impressed by celebrities, dignitaries, and the airs so dear to Manhattanites. “My main memory of Lou was that he had a tremendous sense of satire,” recalled high-school friend John Shebar. “He had a certain irreverence that was a little out of the ordinary. Mostly he would be making fun of the teacher or doing an impersonation of some ridiculous situation in school.”

Much Jewish humor took on a playfully cutting edge, intending to humble a victim in the eyes of God. Despite his modest temperament, Sidney Reed possessed a potent vein of Jewish humor, which he passed on to his son. As a child Lewis mastered the nuances of Yiddish humor, in which one is never allowed to laugh at a joke without being aware of the underlying sadness deriving from the evil inherent in human life. A family friend, recalling a visit to the Reed household, commented, “Lou’s father is a wonderful wit, very dry. He’s a match for Lou’s wit. That’s a Yiddish sense of humor, it’s very much a put-down humor. A Yiddish compliment is a smack, a backhand. It’s always got a little touch of mean. Like, you should never be too smart in front of God. Only God is perfect, and you should remember as pretty as you are that your head shouldn’t grow like an onion if you put it in the ground. You can either take it personally, like I think Lou unfortunately did, or not.”

During Lou’s childhood, Sidney Reed’s sense of humor had curious repercussions in the household. His well-aimed barbs often made his son feel put-down and his wife look stupid. Far from being resentful, Toby admired her husband for his obvious wit. Lou, however, was not so generous. “Lou’s mother thought she was dumb,” recalled a family friend. “I don’t think she was dumb. Lou thought she was dumb for thinking that his father was so clever. I think it was just jealousy. I think it was the boy who wanted all of his mother’s attention.” According to another friend, not only was Sidney Reed a wit, but he maintained a great rapport with Toby, who loved him dearly—much to the chagrin of the possessive, selfish, and often jealous Lewis. “I remember his mother was always amused by his father. His mother admires his father and thinks it’s too bad that Lou doesn’t see his father the way he is.”

One friend who accompanied Lou to school daily recalled that Toby Reed smothered her son with attention and concern. “I think his mother was fairly overbearing. Just in the way he talked about her. She was like a protective Jewish mother. She wanted him to get better grades and be a doctor.” Such attentions, of course, were fairly typical of full-time mothers in the family-oriented fifties. Allen Hyman never found her unusual. “I always thought Lewis’s mother was a very nice person,” he said. “She was very nice to me. I never viewed her as overbearing, but maybe he did. My experience of his parents was that they were very nice people. He might have perceived them as being different than they were. My mother and father knew his parents and my mother knew his mother. They were very involved parents. His mother was never anything but really nice. Whenever we went there, she was anxious to make sure we had food. His father was an accountant and seemed to be a particularly nice guy. But Lewis was always on the rebellious side, and I guess that the middle-class aspect of his life was something that he found disturbing. My experience of his relationship with his parents when we were growing up was that he was really close to them.

“His mother and father put up with a lot from him over the years, and they were always totally supportive. I got the impression that Mr. Reed was a shy man. He was certainly not Mr. Personality. When you went out with certain parents, it was fun and they were the life of the dinner and they bought you a nice meal, but when you went out with Sidney Reed, you paid. When you’re a kid, that’s unusual. The check would come and he’d say, ‘Now your share is …’ Which was weird. But that was his thing, he was an accountant.”

Lou’s father was very quiet; his mother had a lot more energy and a lot more personality. She was an attractive woman, always wore her hair short, had a lovely figure and dressed immaculately. “He’d always found the idea of copulation distasteful, especially when applied to his own origins,” Lou wrote in the first sentence of the first short story he ever published. The untitled one-page piece, signed Luis Reed, was featured in a magazine, Lonely Woman Quarterly, that Lou edited at Syracuse University in 1962. It hit on all the dysfunctional-family themes that would run through his life and work.

His quixotic/demonic relationship to sex was clearly intense. Lou either sat at the feet of his lovers or devised ingenious ways to crush their souls. The psychology of gender was everything. No one understood Lou’s ability to make those close to him feel terrible better than the special targets of his inner rage, his parents, Sidney and Toby. Lou dramatized what was in 1950s suburban America his father’s benevolent dominance into Machiavellian tyranny, and viewed his mother as the victim when this was not the case at all. Friends and family were shocked by Lou’s stories and songs about intra-family violence and incest, claiming that nothing could have been further from the truth. In the story, Lou had his mother say, “Daddy hurt Mommy last night,” and climaxed with a scene in which she seduced “Mommy’s little man.” Lou would later write in “How Do You Speak to an Angel” of the curse of a “harridan mother, a weak simpering father, filial love and incest.” The fact is that Sidney and Toby Reed adored and enjoyed each other. After twenty years of marriage, they were still crazy about each other. As for violence, the only thing that could possibly have angered Sidney Reed was his son’s meanness to his wife. However, these oedipal fantasies revealed a turbulent interior life and profound reaction to the love/hate workings of the family.

In his late thirties, Lou wrote a series of songs about his family. In one he said that he originally wanted to grow up like his “old man,” but got sick of his bullying and claimed that when his father beat his mother, it made him so angry he almost choked. The song climaxed with a scene in which his father told him to act like a man. He did not, he concluded in another song, want to grow up like his “old man.”

Reed’s moodiness was but one indication that he was developing a vivid interior world. “By junior year in high school, he was always experimenting with his writing,” Hyman reported. “He had notebooks filled with poems and short stories, and they were always on the dark side.” Reed and his friends were also drawn to athletics. Freeport High was a football school. Under the superlative coaching of Bill Ashley, the Freeport High Red Devils were the pride of the town. Lou would claim in Coney Island Baby that he wanted to play football for the coach, “the straightest dude I ever knew.” But he had neither the size nor the athletic ability and never even tried out. Instead, during his junior year Lou joined the varsity track team. He was a good runner and was strong enough to become a pole-vaulter. (He would later comment on Take No Prisoners that he could only vault six feet eight inches—“a pathetic show.”) Although he preferred individual events to team sports, he was known around Freeport as a very good basketball player. “Lou Reed was not only funny but he was a good athlete,” recalled Hyman. “He was always kind of thin and lanky. There was a park right near our house and we used to go down and play basketball. He was very competitive and driven in most things he did. He would like to do something that didn’t involve a team or require anybody else. And he was exceptionally moody all the time.”

Allen’s brother Andy recalled that it was typical of Lou to maintain a number of mutually exclusive friendships, which served different purposes. Allen was Lewis’s conservative friend, while his friend and neighbor Eddie allowed him to exercise quite a different aspect of his personality. “Eddie was a real wacko,” commented another high-school friend, Carol Wood, “and he only lived about four houses away from Lou. He had all these weird ideas about outer-space Martians landing and this and that. During that time there was also a group in town that was robbing houses. They were called the Malefactors. It turned out that Eddie was one of them.”

“Eddie was friendly with Lou and with me, but Eddie was a lunatic,” agreed Allen Hyman. “He was the first certifiable person I have ever known. He was one of those kids who your mother would never want or allow you to hang out with because he was always getting into trouble. He had a BB gun and he would sit up in his attic and shoot people walking down the street. Lou loved him because he was as outrageous as he was, maybe more. He used to get arrested, he was insane.”

“There was a desire on Lewis’s part—of course I didn’t know this at the time—to be accepted by the regular kinds of guys, and on the other hand he was very attracted to the degenerates,” Andy recalled. “Eddie was kind of a crazy guy who was into petty theft, smoking dope at a very early age, and into all kinds of strange stuff with girls. And Lewis was into all that kind of stuff with Eddie while he was involved with my brother in another scene.” Having managed to convince his parents to buy him a motorcycle, Lou would ride around the streets of Freeport in imitation of Marlon Brando.

Where Lou spent his troubled teen years in Freeport. (Victor Bockris)

According to his own testimony, what made Lewis different from the all-American boys in Freeport was the fact, discovered at the age of thirteen, that he was homosexual. As he explained in a 1979 interview, the recognition of his attraction to his own sex came early, as did attempts at subterfuge: “I resent it. It was a very big drag. From age thirteen on I could have been having a ball and not even thought about this shit. What a waste of time. If the forbidden thing is love, then you spend most of your time playing with hate. Who needs that? I feel I was gypped.”

“There was no indication of homosexuality except in his writing,” said Hyman. “Towards our senior year some of his stories and poems were starting to focus on the gay world. Sort of a fascination with the gay world, there was a lot of that imagery in his poems. And I just thought of it as his bizarre side. I would say to him, ‘What is this about, why are you writing about this?’ He would say, ‘It’s interesting. I find it interesting.’”

“I always thought that the one way kids had of getting back at their parents was to do this gender business,” recalled Lou. “It was only kids trying to be outrageous. That’s a lot of what rock and roll is about to some people: listening to something your parents don’t like, dressing the way your parents won’t like.”

Throughout his adolescence, Lou was saved by his real passion, rock and roll. Lou had fallen for the new R&B sounds in 1954, when he was twelve. Almost instantly, he had started composing songs of his own. Like his fellow teenager Paul Simon, who grew up in nearby Queens, Lou formed a band and put out a single of his own composition at the age of fifteen, appropriately called “So Blue.” To Lou’s parents, these early signposts of a musical career were ominous. Their dreams of having their only son become a doctor or, like his father, an accountant were vanishing in the haze of pounding music and tempestuous moods. Since puberty Lou had honed a sharp edge, wounding his parents with both public and private insults. In his teens, Lou led Mr. and Mrs. Reed to believe he would become both a rock-and-roll musician and a homosexual—the stuff of nightmares for suburban parents of the 1950s. Actively dating girls at the time, and giving his friends every impression of being heterosexual, Lou enjoyed the shock and worry that gripped his parents at the thought of having a homosexual son. “His mother was very upset,” recalled a friend. “She couldn’t understand why he hated them so much, where that anger came from. At first, they had no malice, they tried to understand. But they got fed up with him.”

Reed playing in one of his highschool bands, the C.H.D. or, backwards, Dry Hump Club.

Throughout his teens, Lou would try anything to break the tedium of life in Freeport, especially if it was considered outside conventional norms. Lou found other characters who were also desperate to elude boredom. One such moment came about indirectly through his interest in music. Every evening, the better part of the high-school population of Freeport and its neighboring towns would tune into WGBB radio to hear the latest sounds, make requests, and dedicate songs. Often the volume of telephone calls to the station would be so great that the wires would get crossed, creating a teenage party-line over which friendships developed. On one occasion, Lou became friendly with a caller. “There was this girl who lived in Merrick,” explained Allen Hyman. “She was fairly advanced for her time, and Lou ended up going out on a date with her. He came back from the date, and he called me up and he said, ‘I’ve just had the most amazing experience. I took this girl to the Valley Stream drive-in and she took out a reefer.’ And I said, ‘Is she addicted to marijuana?’ Because in those days we thought if you smoked marijuana, you were an addict. He said, ‘No, it was cool. I smoked this reefer, it was really great.’”

The decades in which Lewis grew up, the fifties and early sixties, were characterized by middle-class unconsciousness and safety. Much like in the TV series Happy Days, most teenagers were more interested in having a good time than experiencing a wider worldview. “There was not a tremendous amount of consciousness about what was happening on the planet,” commented Allen Hyman. “But Lou was always interested in questioning authority, being a little outrageous, and he was certainly a person who would be characterized as mildly eccentric.”

Lou’s eccentric rebellious side found a lot to gripe about within the conservative, white confines of his neighborhood. Hyman remembered that, though outwardly polite, Lou harbored a hatred of his environment that was manifested in an ill will for Allen’s right-wing father. “The reason he disliked my father so much was because he always viewed him as the consummate Republican lawyer. He was very aware early on of political differences in people. We lived in an area that was Republican and conservative, and he always rebelled against that. I couldn’t understand why that upset him so much. But he was always very respectful to my parents.”

Mr. Reed, along with Mr. Hyman, discouraged musical careers for their sons. “He thought there were bad people involved, which there were,” recalled Lou. However, as Richard Aquila wrote in That Old Time Rock and Roll, “adult fear of rock and roll probably says more about the paranoia and insecurity of American society in the 1950s and early 1960s than it does about rock and roll. The same adults who feared foreigners because of the expanding Cold War, and who saw the Rosenbergs and Alger Hiss as evidence of internal subversion, often viewed rock and roll as a foreign music with its own sinister potential for corrupting American society.”

Lewis enjoyed the comforts of his middle-class upbringing, but acted as if he were estranged from the dominant values of suburban American life. Lou would rewrite his childhood repeatedly in an attempt to define himself. Some of his most famous songs, written in reaction to his parents’ values, have a stark, despairing tone that spoke for millions of children who grew up in the stunned and silent fifties of America’s postwar affluence. One friend put her finger on the pulse of the problem when she pointed out that Lou had an extreme case of shpilkes—a Yiddish term that perfectly sums up his contradictory nature: “A person with shpilkes has to scratch not only his own itch, he can’t leave any situation alone or any scab unpicked. If the teenage Lewis had come into your home, you would have said, ‘My God, he’s got shpilkes!’ Because he’s cute and he’s warm and he’s lovable, but get him out of here because he’s knocking the shit out of everything and I don’t dare turn my back on him. He’s causing trouble, he’s aggravating me, he’s a pain in the ass!” According to Lou, he never felt good about his parents. “I went to great lengths to escape the whole thing,” he said when he was forty years old. “I couldn’t relate to it then and I can’t now.” As he saw himself in one of his favorite poems by Delmore Schwartz: “… he sat there / Upon the windowseat in his tenth year / Sad separate and desperate all afternoon, / Alone, with loaded eyes …”

Another charge Lou would lob at his unprotected parents was that they were filthy rich. This was, however, purely an invention Lou used to dramatize his situation. During Lou’s childhood his father made a modest salary by American standards. The kitchen-table family possessed a single automobile and lived in a simply though tastefully furnished house with no vestiges of luxury or loosely spent funds. Indeed, by the end of the 1950s, what with the shock treatments, Lou’s college tuition, and their daughter Elizabeth’s coming into her teens, the Reeds were stretched about as far as they could reach.

***